By Chris “Junior” Cannon

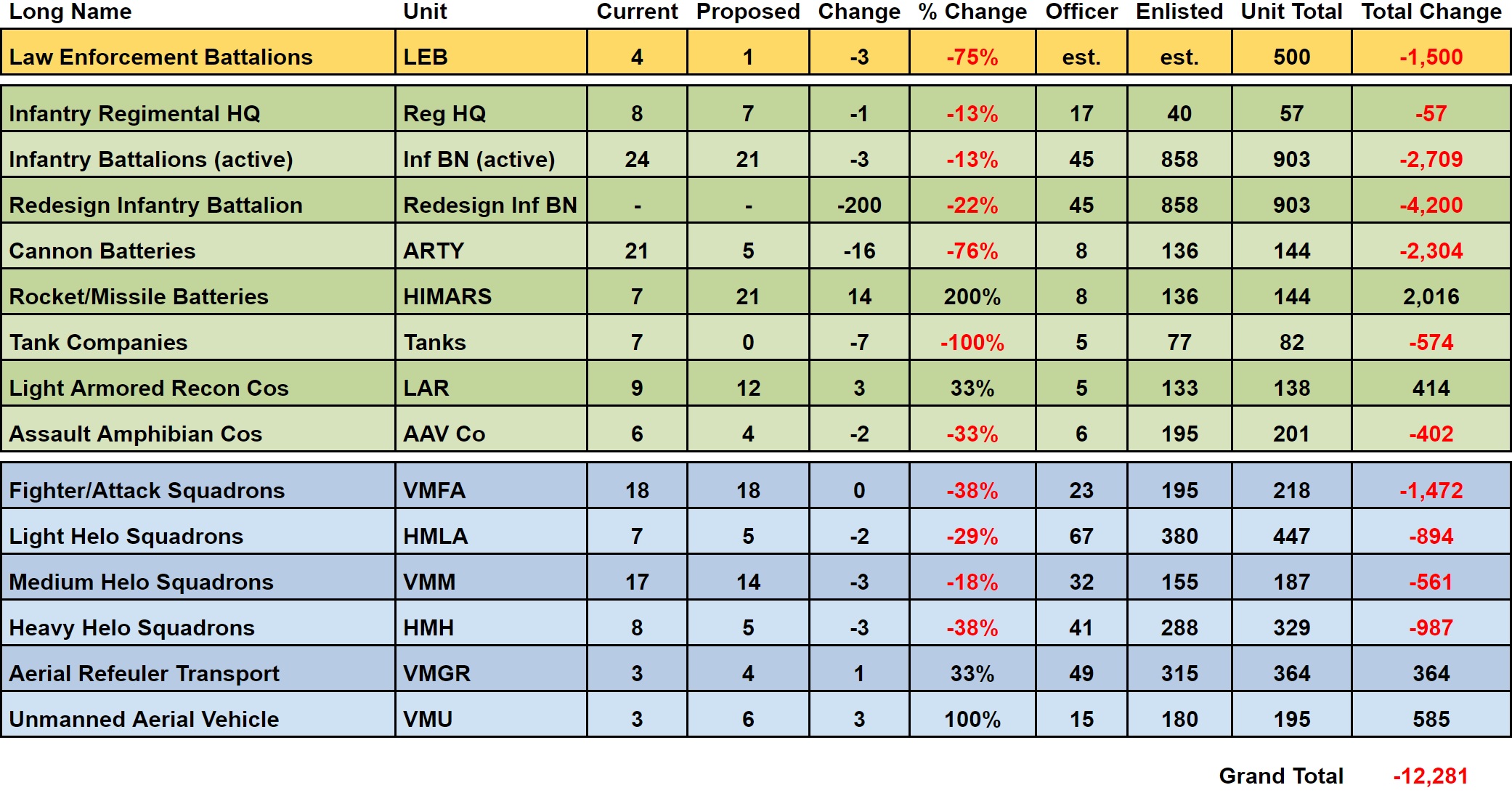

The Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC), General David H. Berger has recently updated his guidance with “Force Design 2030.” The plan calls for major changes, including a reduction of 12,000 active-duty Marines, significant reductions in manned aviation, and a suggested reallocation of $12 billion (presumably over 10 years) to implement force design changes. The impetus behind Force Design 2030 is the 2018 National Defense Strategy, which states “new concepts of warfare and competition that span the entire spectrum of conflict require a Joint Force structure to match this reality.” Figure 1 below shows the CMC’s planned reduction in force levels.

Col. T. X. Hammes (USMC, ret.) and LtCol. Frank Hoffman (USMC, ret.) offer different versions of this chart, but their analysis is incomplete without arriving at the reduction of 12,000 Marines that CMC suggests. The proposed changes remove about 30 percent of infantry billets, but there appears to have been an absence of analysis to this divestment because the number was not well-known or understood. Hoffman states: “Ultimately, this is not a radical shift of force capabilities or capacity.” Limiting some F-35 squadrons to 10 aircraft (in transitioning from F/A-18 squadrons with 16 aircraft) was baked in already, but the numbers also suggest divesting roughly 22 percent of all Marine manned aviation. Dropping a quarter of Marine infantry and manned aviation capability is a radical shift. As CMC states in his planning guidance, “Significant change is required to ensure we are aligned with the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS).” A reduction of 12,000 Marines may underestimate the total force structure changes since we do not yet know what changes come with new Marine Littoral Regiments other additions such as “coastal/riverine forces, naval construction forces, and mine countermeasure forces.”

General Berger had a good head start thinking about NDS requirements before becoming Commandant. CMC’s ascension is reminiscent of another service chief who entered the job with a head start for effecting significant change, Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt. Admiral Zumwalt anticipated severe criticism from Congress, from other services, and even from within the Navy for the changes he planned to make. The new CNO’s Navy redesign, Project Sixty, started with rapid, yet deliberate analysis. Zumwalt briefed that analysis to the Secretary of Defense only 72 days after taking over as CNO, and to all Navy flag officers and Marine generals a week later.

When Zumwalt stepped into the job as the youngest CNO ever, major decisions were made in the shadow of Admiral Hyman Rickover, father of the nuclear Navy. Rickover had been on active duty since before Zumwalt was born, had personal influence in the Navy, the Senate, and the Atomic Energy Commission, and would serve for eight more years after Zumwalt retired. While General Berger has no modern equivalent of Admiral Rickover to scrutinize his every move, unfortunately, the mechanisms for change within the Department of Defense churn more slowly than they did for Admiral Zumwalt and Force Design 2030.

There are three ways that Marines can help the Commandant reduce the inevitable friction associated with changing the Marine Corps to match emerging operational realities: creativity, concepts, and communications.

Creativity

The Commandant needs our help in developing creative solutions to the shortfalls in the analysis and existing capability gaps. From the outset he has asked for input, stating in his Commandant’s Planning Guidance (CPG): “I expect Marines to be prepared to provide their leaders – me included – with critical feedback, ideas, and perspective.” There are multiple online forums where Marines have developed serious feedback for the Commandant. Additionally, the Marine Corps Gazette established a Call to Action section dedicated to Force Design 2030. However, these articles and the discussion forums tend to focus on strategy, concepts, and other commentary instead of the more specific actionable recommendations the Commandant needs. Still, some actionable items already exist within these forums. Some focus on the exact gaps that the Commandant has listed, such as how to absorb new expeditionary capabilities, how to fight in a degraded command and control environment, and field affordable and plentiful capabilities for the future amphibious portion of the fleet.

But to properly harness this creative feedback, the Marine Corps needs an official forum to capture, review, board, and take action on this input. The Commandant needs a forum where – after rigorous analysis and appropriate staffing – short, single-issue position papers can reach him and his staff directly. Force Design 2030 lists 12 Integrated Planning Teams (IPTs) established to assess changes in the future force. But General Berger is still unconvinced that these IPTs are meeting the need for output. Single issue position papers from the force can help the IPTs focus on the most relevant issues in these gaps: logistics, infantry battalion reorganization, ARG/MEU redesign, and light armored reconnaissance analysis. These papers should include recommended solutions in terms of the design levers suggested in Force Design 2030. Standing and future IPTs should be able to consolidate the best submissions, conduct a meta-study of the reviews, and determine which ideas deserve a formal approval board or the Commandant’s attention.

This idea is based on recent history. General Robert B. Neller, the previous Commandant, actively solicited such ideas through quarterly innovation challenges in FY18 and FY19. An open forum would support a broad review process, which Marines and civilians would provide. Once a forum was established, General Berger could ensure rapid engagement by requiring Marines to submit papers as part of professional military education (PME) or training requirements. Past Commandants have taken somewhat similar actions, such as General James T. Conway when he required all Marines (twice) to read Lieutenant General Victor H. Krulak’s First to Fight. A more extreme precedent comes from the 1930s when Brigadier General James C. Breckinridge suspended some courses at what is now known as Marine Corps War College, “… so that staff and students could devote their full attention to developing …” new amphibious doctrine. Another recent example of soliciting such input comes from the founding of the Department of Defense’s Joint Artificial Intelligence Center in 2018. It took a year, but DoD also established an independent commission (four working groups and three special projects) to help the government determine requirements for AI. To help move the conversation forward, the commission’s co-chairs, former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work and former Google and Alphabet CEO Eric Schmidt, immediately put out a call for articles.

These types of position papers could come from observations during exercises, from experiments, from wargames, and from detailed budgetary planning. Some of this input will need to be resubmitted or rediscovered. Input should come from analysts and operators, civilians and Marines, operations officers and chief warrant officers, and from students at all six schools under Marine Corps University. It should be objective, evidence-based, and brief; analysis not advocacy.

Concepts

The Force Design 2030 update goes into some depth explaining how wargames have impacted strategic thinking. The consensus is that many if not most Indo-Pacific wargame results do not bode well for U.S. forces in the current environment, e.g. “Some end in a rapid Chinese fait accompli, such as the seizure of a disputed island with minimal cost, while U.S. and allied leaders dither.” The Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concept describes the Marine Corps’ contributions to prevent such fait accompli victories by peer adversaries. As one recent study suggests: “Without a strategy designed to prevent a fait accompli, the United States might lose a war before alternative approaches have time to be effective.” The hallmark of EABO has been F-35Bs operating from expeditionary bases, primarily as a broad area sensor, not a shooter. But according to former Deputy Defense Secretary Work, “the F-35 rules the sky when it’s in the sky, but it gets killed on the ground in large numbers.” Concept development remains the responsibility of the Marine Corps Combat Development Command (MCCDC) and the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab (MCWL). But as the Commandant’s order on concept development states, Training and Education Command should “encourage the generation of unofficial concepts.”

The Commandant needs our help in completing the new concepts called for in Force Design 2030. With the EABO concept as of yet unsigned and further specifics behind “Stand-in Forces” as of yet unwritten, a lot of analysis remains to validate future Marine Corps employment.

As CMC continuously emphasizes, this concept requires an understanding of how Marine forces fit within the Joint Force. The Army has its Multi-Domain Operations concept designed to succeed in U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. However, MDO is at odds with EABO: “MDO primarily seeks to defeat A2/AD networks to enable joint freedom of maneuver and roll back an adversary’s gains after the fact,” whereas EABO aims to deny an adversary access to areas in the first place. The Air Force already has the budget approval to field an Advanced Battle Management System, the Joint All-Domain Command & Control system (JADC2). For a variety of reasons, most notably shipbuilding, the Navy is behind the other services in pivoting doctrine and strategy. But the commander of INDOPACOM is still a Navy admiral, like all of his predecessors. Fighting under competing doctrines (MDO versus EABO), with an Air Force command and control system, under a Navy-dominated combatant command, and well within an adversary’s weapon engagement zone, will be a daunting task.

The concepts supporting Force Design 2030 must be complete before they can be explained to Congress in order to get budgeting approved. These concepts must be complete before we can explain USMC force integration to other services and component commanders. Most critically, the functional concepts must be complete before we can develop concepts of operation and employment for Marines to execute and train for. When Zumwalt redesigned the Navy, he had “the assistance of a number of commanders to do some of the spadework and research involved” to complete the concepts. The bar has been raised for modern concept development. To complete the concepts, first, we need a successful strategy built on an “independently verifiable analytic foundation.” Based on CMC’s recent comments about the results of recent wargames, and recent intervention by the Office of the Secretary of Defense in the Integrated Naval Force Structure Assessment, we are not there yet.

Above all, Marines writing official (and unofficial) concepts need to help the Commandant explain the numbers. The CPG makes note of only one weapon range: “We must possess the ability to turn maritime spaces into barriers…This goal requires ground-based [long range precision fires] LRPF with no less than 350NM ranges – with greater ranges desired.” When the CPG was published in July 2019, this would have been illegal, as the U.S. still adhered to the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. Two weeks later, the U.S. formally withdrew from the INF, and now for the first time in over 30 years, American long-range land-based cruise missiles are permitted. This one development alone has opening up a significant array of tactical and operational possibilities.

In order to aid the Commandant in maintaining momentum, we need to better understand, generate, and communicate emerging concepts, capabilities, and conditions.

Communicating

The Commandant needs our help in communicating Force Design 2030. He is already an able communicator – since the day he took the job, the Commandant has made frequent, public statements that Force Design 2030 is his top priority. On day one he published his planning guidance. In October 2019, he spoke at length with the Heritage Foundation at their signature annual lecture. In December, he shared his notes in War on the Rocks and chatted with the publication’s founder in the following April. In March 2020, the Commandant published his update to Phase I and Phase II of Force Design 2030. In mid-May, he published the aforementioned update in the Marine Corps Gazette. CMC also appears to be taking pages out of Zumwalt’s playbook, laying out a list of items for immediate action.

But the Commandant can’t communicate every critical aspect of EABO and Stand-in Forces until the concepts are finished, and some of his latest communications still have room for improvement. His June Gazette article cites only one source, a regrettable quote from Alfred Thayer Mahan: “Much is written of courage in the fleet or in the field; but there is a courage of the closet that is no less praiseworthy and fully as rare, and this is the courage to do battle for a new or unpopular idea.” In yet another similarity to Zumwalt, CMC’s closet courage is indeed praiseworthy. In regard to contemporary strategy, however, invoking Mahan is problematic. Mahan advocated for large surface fleets, focusing on capital ships that would win decisive surface battles and establish persistent “control of the seas.” The construction of large fleets of capital ships is diametrically opposed to the principle of Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO), littoral operations in a contested environment (LOCE), and EABO. Mahan and his adherents focused on “War fleets, bases, concentration of force, and decisive battle.” Our modern concepts suggest that these old focal points are our new liabilities. Mahan’s strategies have been attributed by some historians as contributing directly to World War I and the rise of Europe and America as imperial powers during the period characterized by the Chinese as a century of humiliation (1839-1949).

In order to deter current Chinese military ambition, if there is one name that we should avoid repeating, it is Mahan. Admiral Stansfield Turner, who Zumwalt directed to “write a strategy for the Navy” for Project Sixty, would later deliberately contradict Mahan when he invoked the new term, “sea control” to “connote more realistic control in limited areas and for limited periods of time.” 50 years later, the concept of sea control continues to be “the essence of seapower and is a necessary ingredient in the successful accomplishment of all naval missions.” Our ability to deny adversaries access to the sea from expeditionary advance bases will also be of limited scope in time and space, rather than the more longstanding and unassailable command of the seas Mahan envisioned.

When CMC states that we require “an independently verifiable analytic foundation to our program” he means being able to explain and justify the foundation of our concepts to other services, the Pentagon bureaucracy, and Congress. When CMC explains the analytic foundations for his reasoning, such as when he lays out the results of 18-months of recent wargames, it is easier to build consensus and provide feedback. But when he does not discuss the experimentation and simulation taking place, it makes it much harder to understand the force design process, much less communicate the changes to external audiences.

The Commandant could have easily quoted Haddick, Hammes, or Hoffman (who worked on the 2018 NDS), who have laid the intellectual foundation for Force Design 2030’s reasoning. Perhaps CMC was opting for simpler, more direct message appealing to all Marine audiences. But we need to offer a more in-depth explanation, if not the concept of employment, for asking Marines to live and operate within a peer adversary’s weapon engagement zone.

Early criticism, most of which has been highly constructive, is already incorporated into Force Design 2030. Col. Mark Cancian (USMCR, ret.) whose critique of the product already states that the Commandant’s insistence on building a “single purpose-built future force will be applied against other challenges across the globe,” is misplaced. Active-duty Marines have pointed out that the omission of “maneuver warfare” from Force Design 2030 invites criticism of the process or the Marine Corps’ understanding of its own warfighting principles. The most critical response to date has come from former Secretary of the Navy (and Senator) James Webb. Secretary Webb has a negative impression so far but especially took great exception to the choice of the introductory quote to Force Design 2030. “The giants of the past…were passed over, in favor of a quote from a professor at the Harvard Business School who never served. Many Marines, past and present, view this gesture as a symbolic putdown…” Given the rancor reflected in some remarks like Secretary Webb’s, we should not always expect the Commandant to dignify criticism with comment. However, we should be prepared to publicly address fair criticism that has a negative perspective on the current process.

CMC must be clearer in his communication going forward. The Force Design 2030 update states that the Marine Corps will conduct a “Divestment of Marine Wing Support Groups.” This single sentence could imply a reduction of 8,000 MWSG Marines – a divestment likely designed to create space for these undetermined additions. Or it could mean only the headquarters of these groups, a significantly smaller manpower offset. Right now, it is unclear.

CMC should communicate more about modern threat environments by updating the professional reading list. The list should have many more article-length entries, readings that Marines can read in minutes, not days or weeks. Quarterly updates to the list may be more appropriate than annual changes to keep current and relevant subjects in Marines’ thoughts. The reading list should also be partiality populated by the very best of the previously suggested position papers, after IPT review and CMC approval. And some of these readings should be recommended with an eye toward the average Marine’s role in future fights. It is much more critical and accessible for most Marines to understand China’s and Russia’s operational capabilities and tactics than it is for them to internalize (or defend) broader organizational reforms.

Conclusion

Creativity is required to provide CMC with the input he has requested to complete the Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030. This creativity needs to be crowd-sourced throughout the Marine Corps, such as with a call for focused, single-issue position papers. The papers need to be published in a dedicated forum, where CMC’s IPTs can easily digest and analyze the merits of each. This will capitalize on current experiments, ongoing exercises, and the past 20 years of hard-earned Marine Corps operational experience. The concepts must be integrated with the Navy and built on an independently verifiable analytic foundation. While MCCDC and MCWL have the lead on concepts, their foundational work should be expanded by Marines and activities able to contribute to wargaming and analysis, or else the concepts are likely to resemble the “advocacy” that CMC has warned against and not be “independently verifiable.”

The message needs to be clearer. This includes setting the agenda to address expected political and budgetary opposition. This includes properly preparing Marines by educating them on ever more threatening operating environments and adversary capabilities. We should be thankful for the Commandant’s leadership on this and other issues. But it will take more than just a top-down approach to implement the change we need to become ready for the new operational environment. The Commandant needs our help.

LtCol Cannon is a reservist with the MAGTF Staff Training Program and as a contractor supports AI/Machine Learning (ML) projects sponsored by the Office of Naval Research. The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. government and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Featured Image: U.S. Marines with Kilo Company, Marine Combat Training Battalion, School of Infantry – West, fire M240 medium machine guns during live-fire training at Range 218A on Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, California, Aug. 18, 2020. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Drake Nickels)

Fully concur on the author’s thrust on more creative exploration of concepts, and on shortfalls in communication. I think the author’s comments on my paper are unfounded, as I only assessed approved changes, and thus its erroneous to say that Hammes/Hoffman used the same chart or that our evaluations are incomplete. We did not assess changes CMC deferred or disapproved. I would be concerned about the scale of changes on force generation and management. However, am not using end strength as a criteria for assessing the relevance of the force design in isolation of strategic guidance, desired capabilities and missions. Would recommend our audience consider that. FGH

Taking away the mechanized armor infantry assaults will make the grunts sitting ducks without tank support. We may need them in the next combat situation. General Berger is strategically focused on the Chinese. Anything can happen Russians middle eastern or any other hotspot. From a former USMC Tanker nco.

And how many Chinese soldiers are there? Numbers don’t lie,, we are outmaned.

There are presently 60 + active general’s in the Corp . If you going to cut force . I’d suggest you start cutting their.