A Roomba is useful because it can sweep up regular messes without constant intervention, not because it can exit and enter its docking station independently. Although the Navy’s new X-47B Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle (UCAV) has, by landing on a carrier, executed an astounding feat even for humans, this ability only means our weapons have matured past their typical one-way trips. The real challenge will be getting a UCAV to defend units while sweeping up the enemy without remote guidance (i.e. autonomously). The answer is as close as the games running on your Xbox console.

Player One: Insert Coin

Considering the challenge of how an air-to-air UCAV might be programmed, recall that multiple generations of America’s youth have already fought untold legions of advanced UCAV’s. Developers have created artificial “intelligences” designed to combat a human opponent in operational and tactical scenarios with imperfect information; video games have paved the way for unmanned tactical computers.

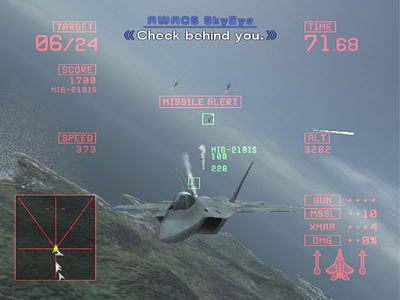

A loose application of video game intelligence (VGI) would work because VGI is designed to operate in the constrained informational environment in which a real-life UCAV platform would operate. Good (i.e. fun) video game AI exists in the same fog of war constraints as their human opponents; the same radar, visual queues, and alerts are provided to the computer and human players. The tools to lift that veil for computer and human are the same. Often, difficulty levels in video games are not just based on the durability and damage of an enemy, but on the governors installed by programmers on a VGI to make competition fair with a human opponent. This is especially evident in Real Time Strategy (RTS), where the light-speed all-encompassing force management and resource calculations of a VGI can more often than not overwhelm the subtler, but slower, finesse of the human mind within the confines of the game. Those who wonder when humans will go to war using autonomous computers fail to see the virtual test-bed in which we already have, billions of times.

This Ain’t Galaga

Those uninitiated must understand how VGI has progressed by leaps and bounds from the pre-programmed paths of games such as the early 1980’s arcade shooter Galaga; computer opponents hunt, take cover, maneuver evasively, and change tactics based on opportunities or a sudden states of peril. The 2000’s Half-Life and HALO game series were especially lauded for their revolutions in AI – creating opponents that seemed rational, adapting to a player’s tactics. For the particular case of UCAV air-to-air engagements, since the number of flight combat simulators is innumerable, from Fighter Pilot on the Commodore 64 in 1984 to the Ace Combat series. Computers have been executing pursuit curves, displacement rolls, and defensive spirals against their human opponents since before I was born.

However, despite its utility, VGI is still augmented with many “illusions” of intelligence, mere pre-planned responses (PPR); the real prize is a true problem-solving VGI to drive a UCAV. That requires special programming and far more processing power. In a real UCAV, these VGI would be installed into a suite far more advanced than a single Pentium i7 or an Xbox. To initiate a learning and adapting problem-solving tactical computer, the DARPA SyNAPSE program offers new possibilities, especially when short-term analog reasoning is coordinated with messier evolutionary algorithms. Eventually, as different programs learn and succeed, they can be downloaded and replace the lesser adaptations on other UCAVs.

I’ve Got the Need, The Need For Speed

When pilots assert that they are more intuitive than computer programs, they are right; this is, however, like saying the amateur huntsman with an AR-15 is lesser trained than an Austrian Arabesquer. The advantage is not in the quality of tactical thought, but in the problem solving rate-of-fire and speed of physical action. A VGI executing air-to-air tactics in a UCAV can execute the OODA loop encompassing the whole of inputs much faster than the human mind, where humans may be faster or more intuitive in solving particular, focused problems due to creativity and intuition. Even with the new advanced HUD system in their helmets, a human being cannot integrate input from all sensors at an instant in time (let alone control other drones). Human pilots are also limited in their physical ability to maneuver. G-suits exist because our 4th and 5th generation fighters have abilities far in excess of what the human body is capable. This artificially lowers aircraft tactical performance to prevent the death or severe damage of the pilot inside.

Pinball Wizard: I Can’t See!

VGI doesn’t have a problem with the how, it’s the who that will be the greatest challenge when the lessons of VGI are integrated into a UCAV. In a video-game, the VGI is blessed with instant recognition; its enemy is automatically identified when units are revealed, their typology is provided instantly to both human and VGI. A UCAV unable to differentiate between different radar contacts or identify units via its sensors is at a disadvantage to its human comrades or enemies. Humans still dominate the field of integrating immediate quality analysis with ISR within the skull’s OODA loop. Even during the landing sequence, the UCAV cheated in a way by being fed certain amounts of positional data from the carrier.

We’ve passed the tutorial level of unmanned warfare; we’ve created the unmanned platforms capable of navigating the skies and a vast array of programs designed to drive tactical problems against human opponents. Before we pat ourselves on the back, we need to effectively integrate those capabilities into an independent platform.

Matt Hipple is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.