The winds of global piracy have shifted, as attacks by West African pirates now exceed those of their Somali counterparts. The Nigeria-based pirates may not yet inspire Hollywood films, but they have prompted regional governments to take collective action. A June 24-25 summit in Yaounde, Cameroon brought representatives from the Economic Community of West African States, the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the Gulf of Guinea Commission together to draft a Code of Conduct concerning the prevention of piracy, armed robbery against ships and illicit maritime activity; now signed by 22 states.

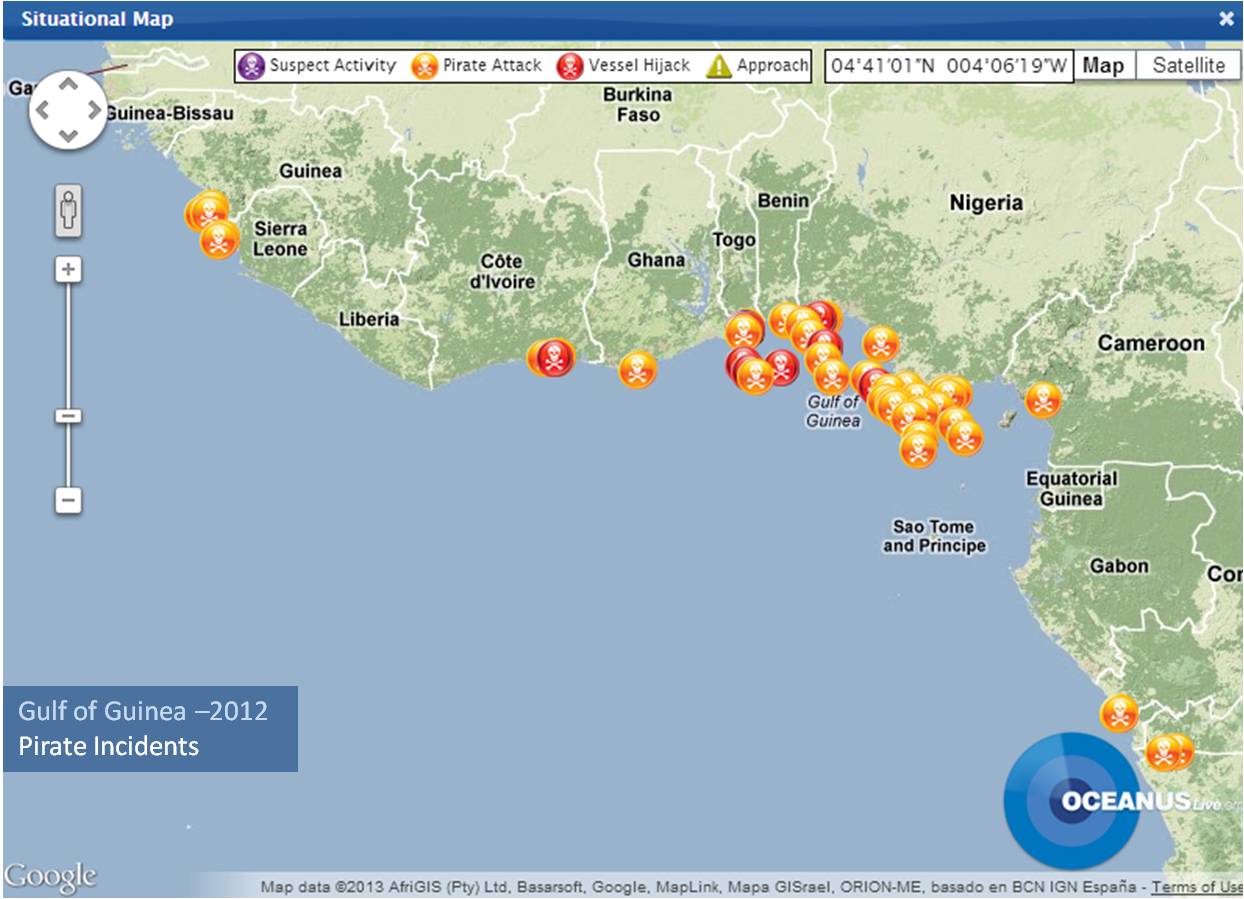

The Gulf of Guinea’s problem is not a dramatic rise in the number of attacks, but the expansion of a criminal enterprise once restricted to Nigerian waters into those of neighboring states. While support vessels operating near Nigeria’s oil fields have been pirate targets for decades, the hijacking and full-scale pilfering of oil tankers is a recent development. This modus operandi first appeared off Benin in December 2010 and has spread to the waters of Togo and Côte d’Ivoire in subsequent years. According to Risk Intelligence data, there were at least 93 tanker attacks in the Gulf of Guinea between December 2010 and May 2013, resulting in some 30 hijackings.

Tanker traffic is particularly dense in the Gulf of Guinea because Nigeria, the region’s largest oil producer, lacks the capacity to refine its own product. Crude oil is thus transported out of Nigeria, refined elsewhere, and then imported back into the country where it is sold at below market rates thanks to a government fuel subsidy. Nigerian criminal syndicates, backed by high-level political and economic patrons, are exploiting this situation by targeting specific tankers for hijacking, offloading their cargo to secondary vessels and then selling the product on the lucrative black market.

A conference of regional experts, held in preparation for the Cameroon summit, estimates that maritime crime is now bleeding the Gulf of Guinea’s states some $2-billion a year in lost port revenue, insurance premiums and security costs. West Africa has now reached a tipping point, like East Africa and South East Asia before it, where the geographic expansion of pirate activity demands a coordinated response. An examination of previous regional efforts to combat piracy thus serves as both a guide and warning for the Gulf of Guinea’s new endeavor.

Regional Counter-Piracy in Context

As a response to increased pirate attacks in the wake of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, 16 states drafted the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) in 2004, which came into effect 2006. The organization is credited with reversing the spike in piracy that coincided with the 2009 global economic downturn, as attacks against ships in the region have steadily fallen from 2010 to 2013. Notable in this success was the establishment in Singapore of an Information Sharing Center (ISC) that facilitates the collection, analysis and dissemination of piracy information among member states.

ReCAAP obligates its members to take legal measures against vessels and individuals who commit acts or robbery or piracy; to extradite such individuals at the request of another state; and to render mutual legal assistance in such cases. Donations from member states fund ReCAAP’s central budget – Singapore and Japan being the largest donors – with additional support coming from out-of-area signatories such as Norway and the Netherlands.

Concerns over state sovereignty have prevented closer cooperation with ReCAAP, as equipment procurement and counter-piracy patrols remain the responsibility of individual states, and national security forces are unable to pursue suspected pirates across maritime boundaries. ReCAAP is also hampered by the unwillingness of Malaysia and Indonesia—the two most pirate-prone states in the region—to ratify the agreement.

As Somali piracy rapidly expanded in the late 2000s, the international community hoped to replicate the success of ReCAAP through a counter-piracy agreement encompassing Eastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Steered by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC) was adopted by nine states in January 2009 and has since expanded to 20 signatories spanning from Jordan to South Africa.

An independent study notes that the DCoC has made significant progress in information sharing, legal reform, and the training of coastguards. At least twelve member states have introduced legal changes to cover the crime of piracy. These developments have been credited for the higher percentage of arrested pirates now being tried and prosecuted in regional courts. The DCoC’s projects are largely financed by an IMO-managed trust fund of some $14-million, funded by maritime states such as Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, and South Korea.

Heading Back West

Influenced by these previous agreements, the Gulf of Guinea’s new Code of Conduct calls on signatories to: share and report relevant information; interdict vessels suspected of engaging in illegal activities; ensure those committing such acts are apprehended and prosecuted; and facilitate the care and repatriation of seafarers subject to illegal activity.

As was done in Singapore, the West and Central African leaders aim to build a regional maritime security center, based in Cameroon, which will facilitate information sharing among governments. The center, it is hoped, will address the massive underreporting of pirate attacks that occurs in the Gulf of Guinea and improve regional maritime domain awareness. However, the examination of previous efforts reveals that regional competition and suspicion are likely to hamper this process. Malaysia refused to join ReCAAP because it viewed the ISC in Singapore as a duplicative competitor to the International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Center based in Kuala Lumpur. Similarly, disagreements within the DCoC resulted in the establishment of three separate information sharing centers in Yemen, Kenya and Tanzania.

Absent from West Africa’s new agreement was any mention of the counter-piracy role that Private Maritime Security Companies (PMSCs) might play in the Gulf of Guinea. Foreign armed guards are not allowed in the territorial waters of local nations, forcing transiting vessels to hire military personnel from regional states and embark and disembark them along route. Several PMSCs were confident that the new agreement would allow them to operate inside the territorial waters of West African states, but concerns over state sovereignty and vested interests in the current system likely prevented such an arrangement from materializing.

Nor are international naval operations likely to be the panacea to West African piracy. At the summit, Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara called on the international community “to show the same firmness in the Gulf of Guinea as displayed in the Gulf of Aden, where the presence of international naval forces has helped to drastically reduce acts of piracy.” However, NATO and the EU have already begun to drawdown assets from their Horn of Africa operations, set to terminate at the end of 2014, and there does not appear to be the political will for cross-continental redeployment. Furthermore, while almost all Somali pirate attacks occur on the high seas, the vast majority of attacks in the Gulf of Guinea take place in territorial waters, primarily those of Nigeria. This serves to render foreign naval vessels both unwelcome, due to local concerns for state sovereignty, and ineffective, as they are unable to operate so close to the shore.

Live Together, Die Alone

The absence of PMSCs and international naval operations means that a counter-piracy regime for the Gulf of Guinea will have to be local and regionally owned. This is a desirable and more sustainable course of action, but it means that the new Code of Conduct must contend with the low level of maritime security capacity that permeates across the region. Nigeria is the only state in the region that possesses a frigate, corvette, or aerial surveillance capacity. However, only an estimated 28% of Abuja’s navy is operational at any given time, meaning that maritime operations usually amount to intermittent sweeps, rather than a continuous patrol presence. The other littoral nations’ “navies” are more accurately described as coastguards. Taken together, West and Central African states are estimated to have fewer than 25 large security vessels available for interdiction efforts. In terms of force multiplying, Nigeria has engaged in joint patrols with Benin since 2011, but there was little indication in the new agreement that other states will join these operations.

As was the case with the DCoC, the IMO has established a trust fund for the Gulf of Guinea that will allow donor states to offset capacity building costs, and it is advisable that the U.S, EU, Japan and others use this as a common channel to coordinate their existing security efforts in the region. Not limiting itself to carrots, the U.S is also trying to exert pressure on Nigeria by issuing a 90-day ultimatum (set to expire at the end of August) to improve port security or face the diversion of U.S-flagged shipping.

While piracy is now a regional issue for the Gulf of Guinea, this ultimatum highlights the fact that the drivers of the crime and its ultimate solution both lay in Nigeria. The country’s fuel subsidies and the lack of local refining capacity are at the root of West Africa’s petroleum black market, and endemic corruption has protected the economic and political elites suspected of profiting from it. Inequality and local grievances in the Niger Delta have been only superficially addressed by payments from a government amnesty program, leaving a massive pool of unemployed young men who see piracy and oil theft as their ticket out of poverty.

Off the coast of Somalia, international naval operations, regional agreements and private armed guards have helped to suppress and contain piracy. In the Gulf of Guinea, enhanced regional cooperation – through information sharing, capacity building, and joint patrols – should serve to roll back the geographical expansion of Nigeria’s pirate gangs. In both cases however, a permanent solution rests within the state that gave rise to regional piracy. Closer maritime coordination in the Gulf of Guinea is a welcome development, but the road to secure marine environment will ultimately have to run through Nigeria.

James Bridger is a maritime security consultant and piracy specialist at Delex Systems Inc. He can be reached at [email protected]