Read Part One here.

By William J. Prom

Part One discussed the U.S. Navy’s failures to effectively prosecute the war at sea and defend the maritime frontier during the War of 1812. The final objective, to maintain superiority on the lakes, stands apart from the rest of the U.S. Navy’s performance in the war. Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan recognized, “[t]hat even the defects of preparation, extreme and culpable as these were, could have been overcome, is evidenced by the history of the Lakes.”1 Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough’s preparation and execution on Lake Champlain stands in particular contrast to the greater Navy’s ability to demonstrate the value of enemy-oriented planning and shipbuilding.

An American defense from a Canadian attack (and, for the War Hawks of Congress, the invasion and annexation of Canada) relied on control of Lakes Ontario, Erie, and Champlain. Dense wilderness and mountainous terrain covered most of the U.S.-Canadian border in the early nineteenth century. The Lake Champlain Valley between the Green and Adirondack Mountains provided a corridor for a large army to transit, but passage required control of Lake Champlain for transportation and logistical support. The lake runs 107 miles long, but is only 14 miles at its widest, and drains north into the St Lawrence River via the Richelieu River.

Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton assigned Lieutenant Thomas Macdonough to command the U.S. Naval forces on Lake Champlain on September 28, 1812.2 The U.S. Navy controlled the lake until June 1813 when one of Macdonough’s lieutenants grounded the sloops Growler and Eagle while trying to chase down British gunboats. Once raised, the British rechristened the sloops Finch and Chubb, respectively. All Macdonough had left was another sloop in need of repair and two unmanned gunboats.3 The British, under Commander Daniel Pring, destroyed the American barracks and storehouses and captured the few remaining private vessels on the lake. Macdonough had to race to buy, build, and repair enough ships to reconstitute his fleet. On August 3, two British sloops and a galley attacked Macdonough’s squadron while moored for repairs at Burlington, Vermont. The British seized two small craft and departed. Macdonough, now a Master Commandant, suffered a serious shortage of officers, seaman, ships, and ordnance.4 Despite commanding the lake, Pring could not dislodge Macdonough from the bottleneck that prevented the British Army from advancing south. After spying the British bring several galleys from the St. Lawrence River to their base at Isle aux Noix, Macdonough convinced the new Secretary of the Navy, William Jones, to send men, supplies, and ordnance to build fifteen galleys of his own.5 Many of these resources, however, went to constructing something much more powerful than a galley.

The Arms Race

After Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry’s victory on Lake Erie on September 10, 1813, the Lake Champlain Valley became the British army’s best avenue for invasion.6 Anticipating the inevitable British attack, Macdonough’s shipbuilding accelerated while at winter quarters on the mouth of Otter Creek. In addition to more gunboats, Macdonough’s shipwrights constructed the 700-ton corvette Saratoga in only forty days. Saratoga carried eight 24-pound long guns and six 42-pound and twelve 32-pound carronades. Macdonough also purchased a steamboat that was under construction, but determined the machinery too unreliable and rigged it as a schooner instead. Named Ticonderoga, the almost-steamer carried eight 12-pound and four 18-pound long guns, and five 32-pound carronades. When the ice cleared in April, Macdonough launched Saratoga and six new gunboats, albeit lacking full armaments and crews.7

On May 14, British Captain Pring, with his new brig Linnet and eight galleys, attempted to obstruct the mouth of Otter Creek before Macdonough’s squadron could enter the lake but an American artillery battery at the site repelled him.8 Two weeks later Macdonough entered the lake with Saratoga, Ticonderoga, several galleys, and the sloop Preble, armed with seven 12-pound and two 18-pound long guns.9

Shortly after reclaiming superiority on the lake, four British deserters informed Macdonough that Pring laid a keel for a ship equal to Saratoga and expected the arrival of eleven more galleys. By July, news confirmed the new ship would be a frigate much larger than Saratoga. Macdonough intercepted spars intended for the frigate to slow construction, but feared that after its completion in early August Pring, “will make a bold attempt to sweep the lake.”10 Secretary Jones wished to avoid another, “irksome contest of ship building,” that doesn’t lead to a decisive action like on Lake Ontario, but Macdonough convinced him to send shipwrights and supplies for an eighteen-gun brig.11 Built in nineteen days, the new brig Eagle carried eight 18-pound long guns and twelve 32-pound carronades. On August 27, Macdonough gathered Saratoga, Eagle, Ticonderoga, Preble, Montgomery, and ten galleys near the Canadian border to blockade the British in the Richelieu River.12

Setting the Stage

Further north, British Governor-General Sir George Prevost assembled an army of 14,000 men to invade New York along the western bank of the lake. This was the largest army yet assembled in North America and included many experienced troops fresh from the Peninsular War. He merely waited for the British squadron to remove the Americans from the lake to enable his invasion south. With the addition of a frigate, the British squadron now rated a post-captain for command, so Captain Peter Fisher replaced Pring on June 24, 1814.13 Unsatisfied with Fisher’s slow progress, Admiral Sir James Yeo, the Commander of the Royal Navy on the lakes, replaced him after five weeks with Captain George Downie on September 2.14

In anticipation of the frigate’s arrival and to avoid Prevost’s advancing artillery, Macdonough moved his squadron south. He had more than two years on the lake to learn its geography and character. He determined the deep water of Plattsburg Bay near the middle of the western shore as the ideal site for his defense. Cumberland Head to the northeast and shoals to the south off of Crab Island enclosed the bay, while American artillery overlooking the bay and a six-pound cannon on Crab Island provided additional protection. Transit south to the American position required a north wind to fight the current. The geography of the Bay ensured that same north wind became a head wind upon rounding Cumberland Head to engage Macdonough’s squadron.15

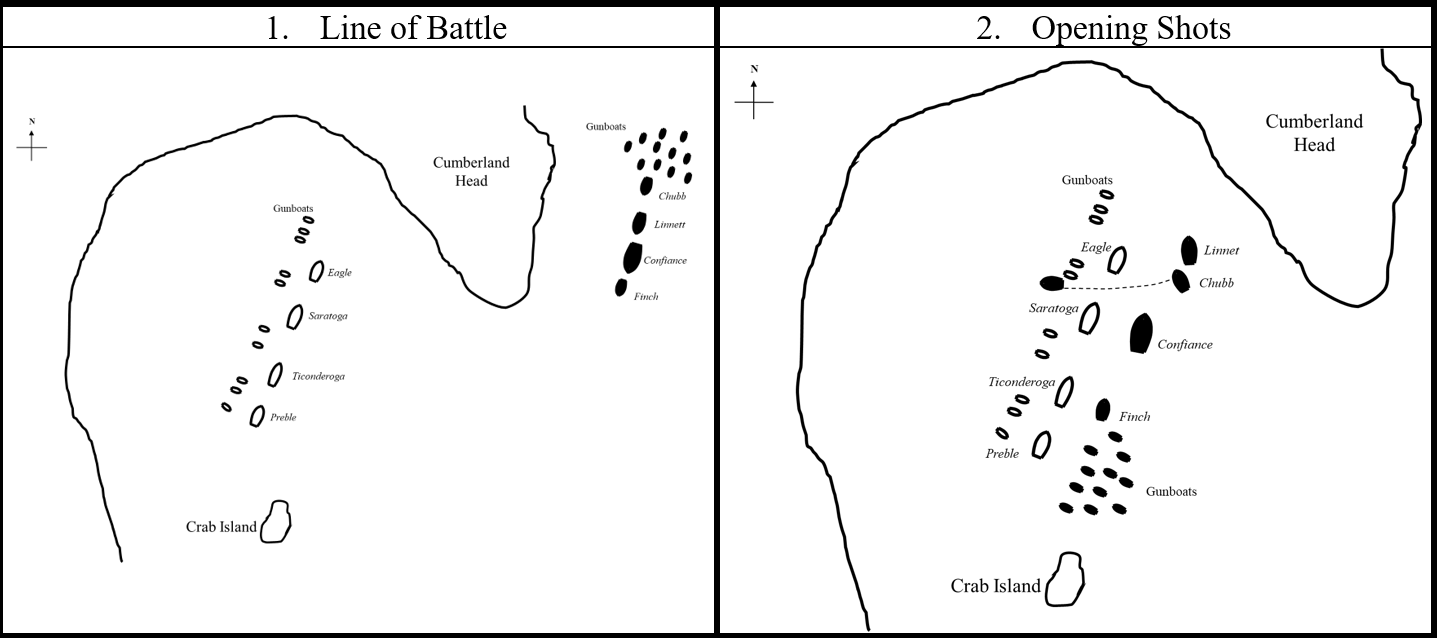

Macdonough anchored Eagle, Saratoga, Ticonderoga, and Preble in a northeastern line from Crab Island to Cumberland Head on September 5. The gunboats formed a second line 40 yards back and spaced between the capital ships. The Eagle was so far forward that any attempt to flank had to negotiate the narrow passage along Cumberland Head, with a head wind, while under heavy fire. The shoals off Crab Island similarly protected the end of the American line. Macdonough forced the British into a vulnerable position if they came around Cumberland Head. Their unarmed bows would bear upon the American broadsides while navigating a cross or head wind. To increase stability for his firing platforms, Macdonough ordered spring lines attached to their bower, stern, and kedge anchor cables. Fighting at anchor presented a stationary target and limited Macdonough to half his firepower. However, with no need to work the sails and only one broadside available, Macdonough could better man his guns with his limited crew.16

For almost a week, Macdonough prepared his defense and rehearsed his crew while Downie raced to complete construction on the newly christened Confiance. At 1200 tons and 160 feet it was the largest ship on the lake. Downie armed it with twenty-six 24-pound long guns, another 24-pounder on a pivot, six 24-pound carronades, and four 32-pound carronades. The frigate also had an onboard furnace to heat shot for a greater lethality. Downie set sail on the morning of September 11, 1814 to seek out Macdonough’s squadron with sailors and carpenters still setting the Confiance’s rigging. He barely managed to assemble a crew, much less drill and train one. The rest of Downie’s force included the brig Linnet with sixteen 12-pound long guns; the sloop Chubb, with eight 18-pound carronades and three six-pound long guns; the sloop Finch, with six 18-pound carronades, one 18-pound and four 6-pound long guns; and twelve gunboats.17

In broadside weight, the two forces were almost identical. The Americans could throw 1,194 pounds to the British 1,192.i The British, however, had a distinct advantage at a long-range fight with long guns making up almost 60 percent of their cannons, compared to 40 percent of the American’s. The greatest disparity existed between the flagships. Saratoga was barely half the size and had only 70 percent as many guns as Confiance.18 Macdonough’s only chance was to engage the British at close range with his carronades, which he forced with his geographic selection.

The Battle of Lake Champlain

Once Downie spied the American position, he set his order of battle: Finch, Confiance, Linnet, and Chubb, followed by his gunboats. He planned to come around Cumberland Head, tack to starboard, and sail into the bay. He matched Linnet and Chubb against Eagle, Confiance against Saratoga, and Finch with the gunboats to harass Ticonderoga and Preble enough to keep them from the main action.19,ii

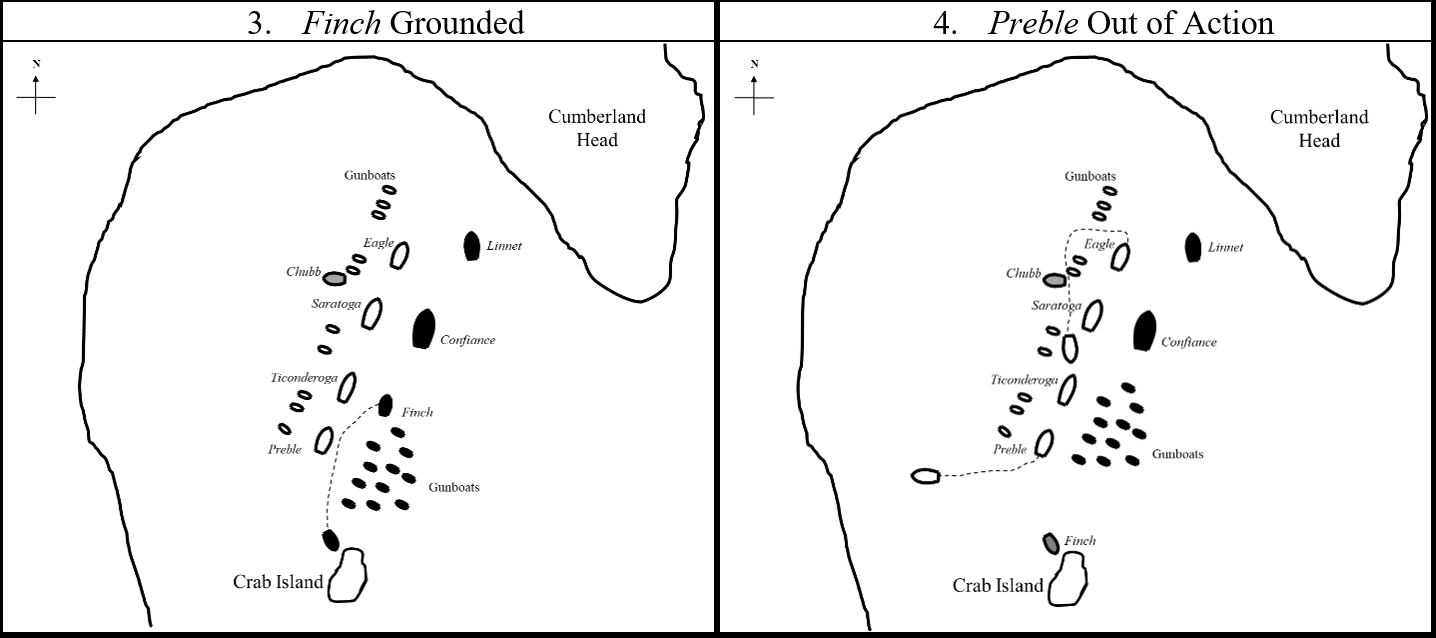

Eagle opened fire on Downie’s approaching squadron shortly after 9:00 A.M., but the rounds fell short. Linnet next engaged Saratoga as it sailed up to its position against the Eagle. It missed as well. After the failed bombardment, Macdonough opened fire with Saratoga and signaled the gunboats to advance and fire on Confiance. The frigate couldn’t answer the heavy barrage until it maneuvered into the bay. Once anchored about 500 yards from Saratoga, Downie fired his first double-shotted broadside. The shot injured or killed several men, and Confiance’s second broadside knocked loose a boom which struck Macdonough unconscious for several minutes. Eagle and the American gunboats shot away Chubb’s rigging before it could attack, and a midshipman from Saratoga recaptured the sloop as it drifted through the American line. Linnet anchored forward of Eagle’s beam and engaged. Finch and the British gunboats attacked Ticonderoga and Preble. An early American shot knocked a cannon from its carriage which fatally crushed Downie. In the carnage, the crew could not find Downie’s signal book to inform Commander Pring on Linnet that he now commanded the squadron.20

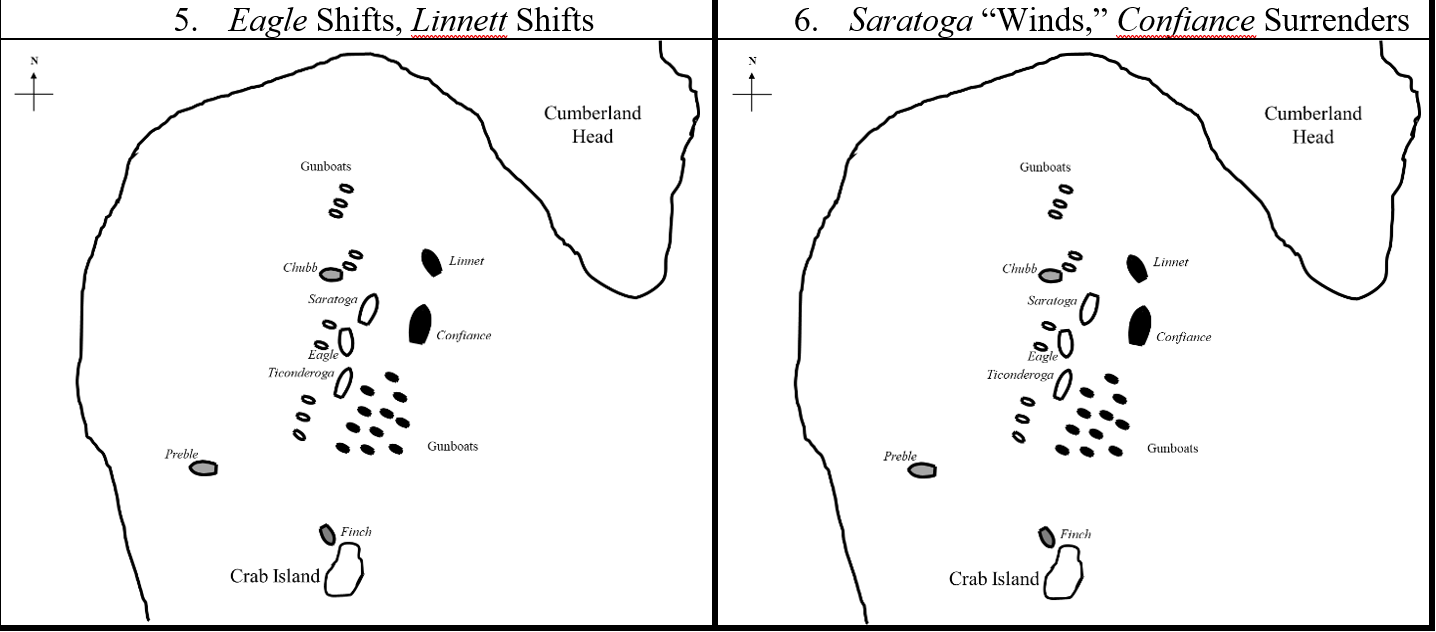

An hour into the battle, Ticonderoga crippled Finch, which then grounded on the shoal near Crab Island. The British gunboats forced Preble from its anchorage, but Ticonderoga kept them at bay. Before sustaining too much damage to continue, Eagle cut its anchor, turned about, and sailed south of Saratoga to engage Confiance. Linnet fought off the American gunboats at the head of the line and moved to fire on Saratoga’s bow. Confiance shot away several of Saratoga’s masts and most of the rigging, and twice set Saratoga ablaze.

Macdonough recounted that, “Our Guns on the starboard side, being nearly all dismounted, or not manageable, a Stern anchor was let go, the bower Cable cut, and the ship winded with a fresh broadside on the Enemy’s Ship.”21 To wind the ship, Macdonough ordered the crew to haul in the starboard kedge anchor, then bring the port kedge hawser forward, under the bow, and then aft again to the starboard quarter. The crew next hauled in the new starboard kedge while paying out the old to complete the 180° pivot.iii The feat took only a matter of minutes. Confiance hastily attempted a similar operation, but only managed half a turn. Already heavily damaged and now listing to port, the frigate could not maneuver to return the Saratoga’s fresh broadside. Confiance soon struck her colors and Saratoga quickly turned to engage Linnet, which struck about fifteen minutes later.22

The British defeat forced Governor-General Prevost’s army back to Canada and secured the American north for the rest of the war. In Mahan’s words, “The Battle of Lake Champlain, more nearly than any other incident of the War of 1812, merits the epithet ‘decisive.’”23

Why Macdonough Won

In many ways, the war on Lake Champlain was a counterexample to the rest of the War of 1812. In this case the British prepared improperly while the American commander did so admirably. Pring, Fisher, and Downie built, provisioned, manned, and trained the squadron—if at all—hastily. Once officers started dying on Confiance, so did order and discipline. Confiance’s inexperienced gun crews loaded cannons with multiple shots but no charges, charges with no shots, or the wadding loaded first. They also failed to replace the quoins that maintain the gun’s elevation. The battle started with guns leveled for point-blank range, but every shot pushed back the quoin and raised the gun higher. Every subsequent shot did less damage as the shots struck amongst the empty rigging rather than the hull. The increasing smoke from the battle obscured the gun captains’ view and left them ignorant to the lack of damage they inflicted.24

The U.S. Navy’s failure in the war and Macdonough’s success both derive from a consideration of the enemy. Congress and the U.S. Navy failed to prepare adequately for a known and much more powerful threat, and the U.S. forces at sea soon found themselves overwhelmed. The limited resources, manpower, and time shaped what Macdonough was capable of building, but he continued to design his fleet specifically to remove the British from Lake Champlain. Once complete, Macdonough fought his enemy-oriented force to great success.

To clear the British from the lake, Macdonough prepared his force by increasing capacity and matching capabilities. The small arms race on Lake Champlain was a struggle to outmatch the opponent’s capacity. Both sides needed to find or build a new ship for each addition on the other side. In order to increase his capacity, Macdonough assembled a fleet of purpose-built warships and converted merchantmen. He purchased and armed merchant vessels like Ticonderoga and Preble for a quick augmentation of his fleet. When he learned of the construction of Confiance and its strength, he rushed to build another ship. As a result, his shipwrights delivered Eagle in nineteen days. Macdonough couldn’t increase the capacity of his force in time to overwhelm the British, but the addition of the Eagle brought him nearly even in broadside weight and number of ships.

Macdonough exploited his time on the lake and his defensive position to set the parameters of the impending battle to make his capabilities most advantageous. The British had more long guns and square sailed ships. In response, Macdonough anchored at a site that nullified the British advantage in long range fire, limited their mobility, and benefited his short-range carronades. His preparations made on Saratoga best demonstrate the value of matching capabilities against the enemy. At 26 guns, Saratoga was significantly outmatched by the Confiance’s 37 guns. By forcing the battle to take place at anchor, Macdonough closed the margin to 13 guns against 19. By setting anchors and spring lines to rotate Saratoga, Macdonough made his full complement of guns available. Despite the initial appearances, Saratoga had the advantage. It was a 26-gun ship armed with heavy carronades at close range versus a ship of 19 the whole time.

Macdonough earned his victory at Lake Champlain with almost two years of preparation oriented on his enemy. He and his shipbuilders worked tirelessly to maintain a capacity on par with the British squadron. But more importantly, he aligned his fleet’s capabilities appropriately against his enemy’s to win the day. Despite this and other victories, the U.S. Navy still lost the war to a distracted adversary. Even while fighting Napoleon in Europe, the Royal Navy managed to destroy, capture, or neutralize by blockade most of the U.S. Navy.

The timeless lessons from the U.S. Navy’s failure to prepare for war are greater than those from Macdonough’s success at Lake Champlain. Military leaders must tailor their strategy to their enemy to create a force that is sized, capable, and deployed adequately against a perceived threat. Although increasing a navy’s size may appear to be appropriate posturing to an apparent threat, a larger navy does not necessarily make for a more effective navy. Even if Macdonough had more ships, it wouldn’t have mattered if they were still mostly armed with carronades. The British could have picked them off at long range in open water with their long guns. It was more important that Macdonough anchored his fleet in a position that nullified the British’s long-range advantage. Military leaders must evaluate their ability to fulfill required capabilities to defend against the enemy as Macdonough did. By understanding an enemy’s capabilities and exploiting their weaknesses, even an apparently disadvantaged force can have the upper hand.

William graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 2009 and served for five years as an artillery officer in the U.S. Marine Corps, deploying to Afghanistan and afloat. He now writes with a focus on early American naval history.

References

i. See Figures 1 and 2

ii. See Figure 3

iii. See Figure 4

1. A.T. Mahan, Sea Power in Its Relation to the War of 1812 (London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Company, 1905), 1:295.

2. Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton to Lieutenant Thomas Macdonough, September 28, 1812, in William S. Dudley and Michael J. Crawford, eds., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. 3 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1985), 1:319-320.

3. Macdonough to Jones, June 4, 1813, Commodore Sir James Lucas Yeo to Croker, July 16, 1813, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 2:490-491, 502-506.

4. Jones to Macdonough, June 17, 1813, Macdonough to Jones, July 11, 1813, Macdonough to Jones, July 22, 1813, Major General Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe to Governor-General Sir George Prevost, 25 July, 1813, Instructions to Lieutenant Colonel John Murray, July 27, 1813, Macdonough to Jones, August 3, 1813, Commander Thomas Everard to Prevost, August 3, 1813, Macdonough to Jones, August 4, 1813, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 2: 512-520.

5. Macdonough to Jones, November 23, 1813, Jones to Macdonough, December 7, 1813, Jones to Macdonough, January 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 2: 603-605, 3:393-395.

6. Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:369-371.

7. Jones to Macdonough, February 22, 1814, Macdonough to Jones March 7, 1814, Governor Daniel D. Tompkins to Jones, March 10, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:396-399; David Curtis Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough: Master of Command in the Early U.S. Navy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2003), 117-120.

8. Macdonough to Jones, May 14, 1814, Commander Daniel Pring to Lieutenant Colonel William Williams, May 14, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:479-483.

9. Macdonough to Jones, May 29, 1814, Macdonough to Jones, June 11, 1814, Macdonough to Jones, June 19, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:504-508, 537-538.

10. Macdonough to Jones, June 29, 1814, Macdonough to Jones, July 9, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:504-508, 537-538.

11. Jones to Macdonough, July 5, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:539

12. Macdonough to Jones, August 12, 1814, Macdonough to Jones, August 16, 1814, Macdonough to Jones, August 27, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:537-542; Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough, 119.

13. Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough, 100; W.M.P. Dunne, “The Battle of Lake Champlain,” in Great American Naval Battles, ed. Jack Sweetman, (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 85.

14. Prevost to Captain George Downie, 9 September 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:598; Borneman, 1812, 204-205.

15. Mahan, Sea Power in Its Relation to the War of 1812, 2:376-377; David Curtis Skaggs, “More Important Than Perry’s Victory,” Naval History 27, no. 5 (October 2013). https://www.usni.org/magazines/navalhistory/2013-09/more-important-perrys-victory.

16. Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough, 125-126; H.C. Washburn, “The Battle of Lake Champlain,” Proceedings 40, no. 5 (September-October): 1373, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1914-09/battle-lake-champlain; Dunne, “The Battle of Lake Champlain,” in Great American Naval Battles, 94.

17. Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough, 117-120; Borneman, 1812, 205-206.

18. Theodore Roosevelt, The Naval War of 1812, 2 vols. (New York: Putnam, 1902), 2:118-121.

19. Pring to Yeo, September 12, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:609-614.

20. Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough, 129-130.

[xxi] Macdonough to Jones, September 13, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:614-615.

22. Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough, 133-134; Borneman, 1812, 210-213; Roosevelt, The Naval War of 1812, 2:124-135; Washburn, “The Battle of Lake Champlain,” Proceedings 40, no. 5 (September-October): 1383.

23. Mahan, Sea Power in Its Relation to the War of 1812, 2: 381.

24. Roosevelt, The Naval War of 1812, 2:127-128; Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough, 132.

Featured Image: Macdonough’s Victory on Lake Champlain, 1814. Watercolor by Edward Tufnell, depicting the U.S. Sloop Saratoga (left center) and the U.S. Brig Eagle (right) engaging the British flagship Confiance (center) off Plattsburg, New York, 11 September 1814. Courtesy of the Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.