By Alex Calvo

This is the second installment in a four-part series devoted to China’s 7 December 2014 document, putting forward her views on the Philippines’ international arbitration case on the South China Sea. Although Beijing is refusing to take part in the proceedings, as confirmed following the Court’s 29 October 2015 ruling on jurisdiction, by issuing this document, and communicating in other ways with the Court, the PRC has failed to completely stay aloof from the case. It is thus interesting to analyze China’s narrative as laid down in that document. Read Part One.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

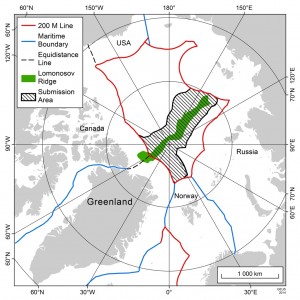

Putting the cart before the horse? China argues delimitation of land territories must come first. The text affirms (6) that “Since the 1970s, the Philippines has illegally occupied a number of maritime features of China’s Nansha Islands, including Mahuan Dao, Feixin Dao, Zhongye Dao, Nanyao Dao, Beizi Dao, Xiyue Dao, Shuanghuang Shazhou and Siling Jiao. Furthermore, it unlawfully designated a so-called ‘Kalayaan Island Group’ to encompass some of the maritime features of China’s Nansha Islands and claimed sovereignty over them, together with adjacent but vast maritime areas,” claiming sovereignty “over Huangyan Dao of China’s Zhongsha Islands and illegally explored and exploited the resources on those maritime features and in the adjacent maritime areas,” and (10) argues that in any case it is not possible to rule “on whether China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea have exceeded the extent allowed under the Convention” until “the extent of China’s territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea” has been determined.

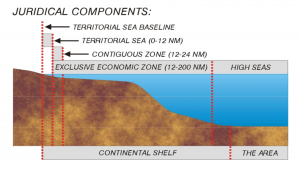

This argument is central to China’s case, being the opposite of one of the pillars of Manila’s arbitration bid, namely that it only concerns the extent and manner that rights are exercised, rather than territorial delimitation, which is out of bounds to the court due to Beijing’s derogation (that is, opt out from that aspect of the convention, meaning that compulsory arbitration does not extend to territoria delimination in the case of China), which Manila acknowledges. To press the issue further, Beijing cites the ICJ, (11) pointing out that “the land dominates the sea.” That is, it argues that one cannot discuss whether the sea is being used in accordance with UNCLOS before a full determination of a country’s land territory has been made, a determination not open to the Permanent Court of Arbitration without Beijing’s consent. The text calls (14) Manila’s attempt to examine the former “contrived packaging” which “fails to conceal the very essence of the subject-matter of the arbitration, namely, the territorial sovereignty over certain maritime features in the South China Sea.” Another, less aggressive, term employed by the text (18) to press home the same point is “putting the cart before the horse.” To support this view, the document argues (18) that there is no precedent “in relevant cases” of any “international judicial or arbitral body” having “ever applied the Convention to determine the maritime rights derived from a maritime feature before sovereignty over that feature is decided.” While international tribunals like the PAC are not, formally speaking, bound to the doctrine of precedent (stare decisis), they do tend to follow previous rulings. However, there have not been a large number of cases, much less a coherent set of rulings, on this issue. Therefore, we may say that there is simply no consistent body of case law on whether it is possible to examine compliance with UNCLOS of a country’s practice at sea in advance of territorial determination.

Appropriation of low-tide elevations: Beijing argues not up to interpretation of UNCLOS. Concerning the “low-tide elevations” that Manila claims to be such and has included in its arbitration bid, saying that they cannot be appropriated, China’s document (23 and 24) argues that “whether or not” they “can be appropriated is plainly a question of territorial sovereignty.” Formerly often referred to as “drying rocks” or “banks,” UNCLOS defines “low-tide elevations” as “a naturally formed area of land which is surrounded by and above water at low tide but submerged at high tide.” The Chinese paper states that it “will not comment” on whether they are “indeed low-tide elevations,” while pointing out that “whatever nature those features possess, the Philippines itself has persisted in claiming sovereignty over them since the 1970s,” citing “Presidential Decree No. 1596, promulgated on 11 June 1978” whereby Manila “made known its unlawful claim to sovereignty over some maritime features in the Nansha Islands including the aforementioned features, together with the adjacent but vast areas of waters, sea-bed, subsoil, continental margin and superjacent airspace, and constituted the vast area as a new municipality of the province of Palawan, entitled ‘Kalayaan.’” China’s position paper cites later Filipino legislation, arguing that while pretending to adjust claims to UNCLOS it does “not vary the territorial claim of the Philippines to the relevant maritime features, including those it alleged in this arbitration as low-tide elevations.” The text accuses Manila of contradicting herself by first asserting in “Note Verbale No. 000228, addressed to Secretary-General of the United Nations on 5 April 2011” that “the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG) constitutes an integral part of the Philippines,” the KIG including among others “the very features it now labels as low-tide elevations,” with the “only motive” being to deny them to China and “place them under Philippine sovereignty.” Furthermore, the position paper argues (25) that UNCLOS “is silent on this issue of appropriation” of low-tide features, citing the ICJ in the 2001 Qatar v. Bahrain ruling, where it stated that “International treaty law is silent on the question whether low-tide elevations can be considered to be ‘territory.’ Nor is the Court aware of a uniform and widespread State practice which might have given rise to a customary rule which unequivocally permits or excludes appropriation of low-tide elevations.” The text also cites a later 2012 ICJ case, the “Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia),” where it stated that “low-tide elevations cannot be appropriated” but argues that the Court “did not point to any legal basis for this conclusory statement. Nor did it touch upon the legal status of low-tide elevations as components of an archipelago, or sovereignty or claims of sovereignty that may have long existed over such features in a particular maritime area,” adding that “the ICJ did not apply the Convention in that case.” Therefore, China’s position paper argues, “Whether or not low-tide elevations can be appropriated is not a question concerning the interpretation or application of the Convention.”

Taiwan: lurking on the background. Taiwan and the “One-China Principle” are not absent from China’s document either, the text (22) accusing Manila of committing a “grave violation” of the principle for omitting Taiping Dao (Island) from the list of “maritime features” described as “occupied or controlled by China.” Instead, the text describes it as being “currently controlled by the Taiwan authorities of China.” This is a reminder that the conflict over the South China Sea is connected with that over Taiwan, in a number of ways. We may ask ourselves whether Manila was departing here from her “One-China Policy.” Was this a warning shot, or merely another example of how state practice concerning Taiwan is moving (sometimes inadvertently) away from Beijing’s strict position in many countries.

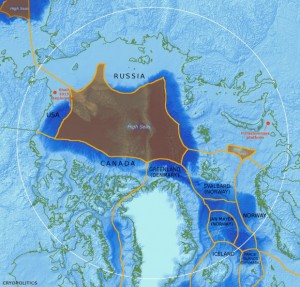

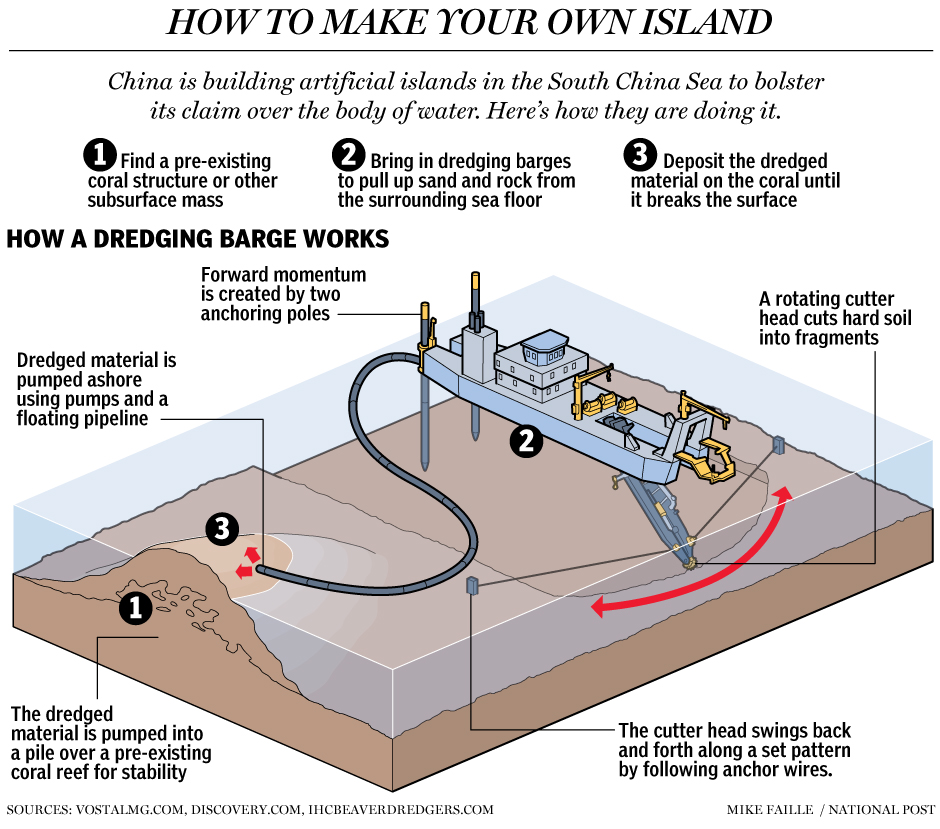

The burning question of freedom of navigation and overflight. Given the current controversy over FON (Freedom of Navigation) operations by the US Navy, along or together with partners and allies, close to China’s artificial islands in the South China Sea, this is an aspect of Beijing’s paper of great interest to observers. Concerning this, section 28 stresses that “China always respects the freedom of navigation and overflight enjoyed by all States in the South China Sea in accordance with international law.” While this is in line with repeated assertions by Chinese authorities, it prompts further doubts on the exact nature of Beijing’s claims, in the sense that if all it was demanding was an EEZ then freedom of navigation and overflight would simply flow from international law, without the need for any concession by the coastal state. The issue is made more complex by the fact that in Beijing’s view the rights of coastal states are more extensive than in the eyes of countries such as the United States, going as far as including the right to authorize or deny military activities such as electronic intelligence gathering, which has been the source of a number of incidents, some of them fatal. Thus, if what China is claiming is an EEZ, is Beijing making a concession and accepting a lesser set of coastal state rights in the particular case of the South China Sea? Alternatively, should we read “freedom of navigation and overflight” as being restricted to civilian ships and planes, or at least not including any activities such as ELINT (electronic intelligence) gathering, prejudicial to the coastal state? Other questions may be prompted by China’s assertion. For example, does this also apply to territorial waters around Chinese islands in the South China Sea? A question made more complex by the fact that there is no agreement over which islands are islands there, in particular given the extensive reclamation work taking place.

Read the next installment here.

Alex Calvo is a guest professor at Nagoya University (Japan) focusing on security and defence policy, international law, and military history in the Indian-Pacific Ocean Region. A member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) and Taiwan’s South China Sea Think-Tank, he is currently writing a book about Asia’s role and contribution to the Allied victory in the Great War. He tweets @Alex__Calvo and his work can be found here.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]