By Peter C. Combe II

In a recent piece for the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), Brent Stricker provided an excellent overview of legal considerations associated with the Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030, concepts for Stand-in-Forces (SIF) and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO). Stricker provides a cogent introduction to targeting, deception and distinction questions if using non-standard platforms, and access, basing, and overflight (ABO) of regional states in the Pacific and South China Seas. This essay is intended to expand on additional legal considerations that the School of Advanced Warfighting student class of Academic Year 2022 encountered during the last year of study.

The Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR) is the Marine Corps’ contribution to the SIF concept. Foundational to the SIF concept is the ability to operate and persist within the enemy’s weapons employment zone (WEZ). In seeking to operate and persist within contested spaces, SIF need not always be Special Operations Forces (SOF), but in many ways they must be SOF-like. This includes not only size, and employment concepts, but enabling capabilities and the attendant authorities as well.

Target Engagement Authority and Criteria

In addition to discussions of the ground, air, and maritime domains a discussion of the legal rules, and authorities associated with other domains and capabilities is relevant to the SIF concept. As important as what the U.S. Joint Force is legally permitted to do, is the question of the level at which those authorities lie.

Cyberspace presents a number of challenges to applying the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) because the United States and China hold different views about how it applies to cyberspace. The official U.S. position is that cyberspace operations can rise to the level of an armed attack if they have sufficient effects or impact systems of sufficient national importance, while the People’s Republic of China (PRC) takes a contrary stance, that LOAC (as a jus in bello matter) is inapplicable in cyberspace. Related is the determination of when and whether a cyberspace operation may rise to the level of an armed attack which justifies the use of force in self-defense pursuant to the U.N. Charter. While the United States and many other nations believe that a cyberspace operation may pose a sufficient jus ad bellum justification for self-defense, the PRC has remained silent on the matter. These divergent views on the jus ad bellum and jus in bello applicability in cyberspace pose the danger of miscalculation, which operational planners and national security practitioners must remain wary of.

The PLA Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) is the primary PLA organization tasked with the conduct of cyberspace operations. In a crisis situation it is possible that the PLASSF may seek to impose cyberspace effects on U.S. naval vessels in the South or East China Seas as a means of demonstrating resolve and on the rationale that such actions could not violate international law, as international law is inapplicable to cyberspace actions. However, the United States may view such an offensive cyberspace operation as equivalent to a use of force against a military vessel, and conclude that the right to use military force in self-defense pursuant to Article 51 of the U.N. Charter has been triggered.

In a deeper discussion of targeting, regardless of domain, we must also address who is authorized to engage a given target. For instance, where does the authority lie to employ various capabilities or to achieve certain effects? During the past 20 years of counterterrorism operations the authority to employ lethal fires was often held at the General/Flag Officer (GO/FO) or Joint Task Force (JTF) level. There were sound reasons for this including the operational imperative to limit civilian casualties and the tactical and operational patience required when dealing with a non-state actor on the other side of the globe. However, requiring GO/FO approval to employ lethal fires may be inappropriate when dealing with Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) or Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) in a communications denied/degraded environment against a near peer competitor.

Degraded communications may prevent distributed tactical units from being able to contact a GO/FO to approve a strike. Similarly, the decision speed required may preclude the ability to fire effectively in modern salvo combat if a tactical unit is required to work through a Joint or Combined Task Force headquarters to take offensive strike decisions. Successful fires in a salvo combat model may require that an MLR Company Commander (i.e., a Marine Captain or Major) be authorized to approve offensive strikes against a PLA-Navy surface combatant.

A similar concern is the need to rely upon allies and partners for access, basing, and overflight (ABO) in any conflict in the Western Pacific. In those instances, the question is likely to arise: which allies and partners, or what other persons or infrastructure are U.S. forces permitted to use lethal force to defend? It is not uncommon for U.S. forces to be permitted to defend a particular partner while that partner is conducting one type of mission, but not others. Similarly, it is common that U.S. forces may be permitted to defend a partner force against some third party actors, but not others.

While national and tactical self-defense often includes the concept of collective self-defense, it is not something the Joint Force can take for granted. It may raise concerns about facilitating indiscriminate lethal targeting by an ally, or being drawn into a wider conflict, and thus limiting the circumstances under which U.S. forces may defend Saudi or Yemeni allies. It could generate concerns about the appropriate degree and level of support to non-state proxies and their compliance with international law. Congressional skepticism has also arisen based on the perception that U.S. forces use “collective self-defense” as a means to skirt Congressional authorizations to use military force. These are difficult questions – and what is operationally expedient may not be politically tenable. Operational planners must be prepared to scope self defense/collective self-defense rules of engagement to manage a number of competing tensions: what is legally permissible, what best serves operational requirements, and what is politically and diplomatically feasible.

Aside from questions about the operational or tactical echelon at which targeting decisions are made, is the human commander’s role in those decisions. Artificial intelligence holds both enormous promise to increase the speed and quality of decision-making, while raising thorny ethical and quasi-legal questions about automation in decisions to use lethal force. Should artificial intelligence work primarily as a decision support tool, or with a “man-on-the-loop” for primarily defensive systems? This discussion is particularly pertinent when considering the possibility that the Marine Corps’ Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR) may be incorporated into the Navy’s Composite Warfare Command (CWC) structure – perhaps using a virtualized version of the Navy’s Aegis Combat System, which enables autonomous defensive engagements based on preset criteria. The Aegis Combat System may also permit automated offensive engagement in certain narrow circumstances.

These capabilities raise the possibility that an MLR/EAB commander may not be the final authority making firing or target decisions. Depending upon the availability of communications, and the MLR’s position within the CWC construct, the MLR may turn into essentially a maintenance and maneuver package for a Navy fires asset. It is further foreseeable that firing decisions are made not by a human (Navy or Marine Corps) commander, but made by automated systems and monitored by naval commanders and staff.

Signature Management:

TAC-D, DISO, Joint MILDEC, Cover, or Something Else?

Signature management and deception also pose challenges, because responsibility to distinguish one’s own forces from civilians is borne by both attackers and defenders. Thus, signature management, including various levels of deception becomes both an imperative and a potential stumbling block. In addition to the distinction issues raised by Stricker’s article, there are administrative and policy requirements that the national security law practitioner must consider. Do certain signature management practices constitute Tactical Deception (TAC-D), Deception in Support of Operational Security (DISO), or Joint Military Deception (MILDEC)?

TAC-D is generally deceptive activity executed at the tactical level of command, for the purpose of influencing enemy commanders to take or forego actions favorable to achieving tactical level outcomes (battles and engagements). DISO targets adversary intelligence services rather than commanders or decision-makers, and seeks to create false indicators or observables that disguise or manipulate the true nature of a unit. Joint MILDEC sits atop the deception pyramid, is a theater level activity to support a Joint campaign, and is normally planned, approved, and conducted at the Combatant Command level in advance of and during a campaign. These are different, and not terribly well understood concepts within the larger Joint Force, and are approvable at different levels of command. Operational planners and national security law practitioners must understand the differences and most importantly the approval levels and timelines, as approving executions in support of Joint MILDEC may take months and require Joint Staff coordination prior to execution.

Other administrative signature management practices may prove no less challenging. The concept of “21st century foraging,” is pitched as a means to help Marine units persist within the PLA weapons employment zone (WEZ) without Joint Force or Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) level logistics. As the PRC continues aggressive efforts to court (and coerce) neighboring countries, it is likely to attempt expansion of its cashless surveillance economy into those countries as well. In these instances, the use of cash may prove untenable and use of government associated credit cards may provide an easily traceable administrative signature. Attempts to use non-attributable credit accounts may implicate the need to staff and approve a cover or cover support plan, which can take significant amounts of time and resources, and will require coordination, approval, and resourcing from outside of Marine operating forces. Operational planners and national security law practitioners at the MEF, MARFOR, and Geographic Combatant Command (GCC) level must familiarize themselves with these concepts to make EABO and DMO feasible.

National Command Authority and Jus Ad Bellum

Other law of armed conflict considerations, more appropriate for the Joint Staff or National Command Authority, also bear consideration. A common scenario in discussions of EABO and SIF is the defense of Taiwan by U.S. forces. Operational planners and national security law practitioners need to understand that the U.S. abrogated the mutual defense treaty with Taiwan (the Republic of China / ROC) in 1979 as part of U.S. efforts to establish diplomatic relations with the PRC. The Taiwan Relations Act (TRA, passed the same year) also does not provide a domestic legal obligation to defend Taiwan, nor an international legal basis to do so. Rather, the TRA permits the Departments of State and Defense to essentially treat Taiwan as a state for Foreign Military Sales and Security Cooperation purposes. This remains an important distinction as fewer than 20 countries recognize Taiwan diplomatically, a number which does not include the U.S. or any permanent member of the U.N. Security Council.

With this context in mind, international law recognizes three traditional justifications for the use of force internationally: (1) under a U.N. Security Council Resolution (UNSCR), (2) self-defense, including collective self-defense of a third party country, and (3) consent of the state in whose territory force is used. The first and last justifications are non-starters in a Taiwan scenario as the PRC is a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council able to veto any potential UNSCR, and the U.S. “one China policy,” affords diplomatic recognition to the PRC in Beijing, not the ROC in Taipei.

Collective self-defense as a jus ad bellum justification is also typically applied to states, and unlikely for the reasons above. The U.S. has also never adopted the “responsibility to protect (R2P),” doctrine as an independent legal basis justifying the use of force in a third country to defend a non-state entity as a means to alleviate internal/domestic violations of International Human Rights Law (IHRL). Furthermore, recent events have called into question the degree to which the R2P doctrine may be falling out of favor in international law circles in the wake of Russia’s pretextual use of the doctrine to justify an aggressive war against Ukraine. However, that may not foreclose the discussion. An under-studied area of law with respect to international law justification is that of executive prerogative.

Presidential prerogative has a long history in the United States, with the country’s earliest presidents arguing over the contours of what the doctrine permitted, and whether or how those actions must be corrected or remedied after the fact in the absence of Congressional authorization. The concept of executive, or “Crown Prerogative,” also has a place in current and former English Commonwealth countries. Sir William Blackstone, the eminent 18th Century British jurist and legal commentator, described it separate and apart from the executive authority to administer the laws passed by Parliament. Because the U.N. Charter is not to the prejudice of Customary International Law (CIL) but rather acts as a sort of augment to existing CIL rules, the concept of executive prerogative may survive in some form as a distinct customary international legal basis to use force (or seize necessary territory) in a third country. These are questions that bear exploration as they relate to EABO specifically, and SIF more generally, especially in light of the President’s recent vow to use military force to defend Taiwan in the face of PLA aggression.

Furthermore, a core assumption of EABO and the Concept for Stand-in-Forces is the ability to operate from third countries in order to hold an adversary at risk. However, there is good reason to believe that many countries in the East and South China Seas will be reticent to ally with the U.S. during an armed conflict. In that case, is the U.S. then precluded from operating in those countries absent a non-consensual occupation of territory? The underlying question in this instance, obligations of an occupying power aside, is whether sovereignty is a rule of international law, or a foundational precept – but NOT a rule – underlying other international legal obligations. This question, combined with the question about presidential and executive prerogative, potentially bears great importance to the future success or failure of EAB operations in the event of armed conflict in the Western Pacific.

Conclusion

The EAB, DMO, and SIF concepts hold a degree of promise for peace time and conflict operations in the littorals and other contested maritime domains. Operational planners and national security law practitioners at the operational level of war must be familiar not only with the legal rules regarding targeting, deception, and signature management, but they must also understand where the authorities do (and should) lie with respect to those activities. They also need to understand how targeting practices have been adopted and adapted during 20 years of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, both from a policy and law perspective. The time may soon arrive when authorities, capabilities and effects which were the domain of a GO/FO commander at a JTF are held at the battalion or even lower level.

Furthermore, U.S. forces will require ABO in third countries in the event of conflict heavily leveraged in the maritime domain, geography demands it no matter which ocean is host to the conflict. Consent from those third countries may be forthcoming, but others may remain reticent or even hostile to accede to U.S. requirements for ABO. Further exploration and understanding of legally available options for non-consensual operations (including lethal operations) is required to assure that ABO and enable effective employment of the new-look Marine Corps.

Lieutenant Colonel Combe is currently assigned to Judge Advocate Division, Headquarters Marine Corps. He recent’y graduated as a resident student at Marine Corps University’s School of Advanced Warfighting. His operational law experience includes serving in the International and Operational Law Branch, Judge Advocate Division and numerous operational deployments in support of conventional and special operations across multiple Combatant Commands. He has written several articles and blog posts on national security law.

The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, the Marine Corps, or any other military or government agency.

Featured Image: OKINAWA, Japan (July 8, 2022) – Reconnaissance scouts assigned to the Maritime Raid Force, 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit wait for a UH-1Y Venom to land during a tactical air control party training on Irisuna Island, Okinawa, Japan, July 8, 2022. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Andrew King)

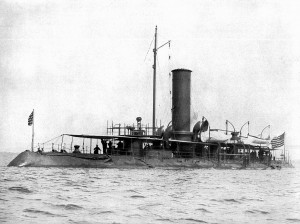

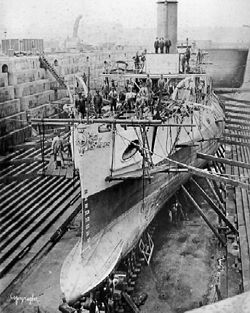

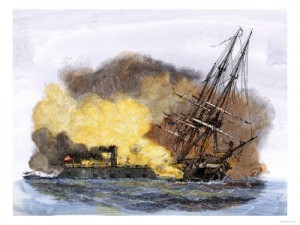

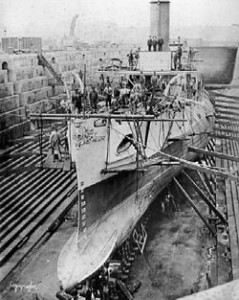

ay color for camouflage, Polyphemus was an expensive experiment soon overtaken by the technology of rapid fire guns. While the Polyphemus also had torpedoes as a weapon, the USS Katahdin,commissioned in 1893 at a cost of over $900,000 was a pure ram with only light weapons. Painted green to camouflage herself in coastal waters, Katahdin was a harbor defense weapon against invading enemy fleets seeking to shell U.S. cities. Although briefly in commission for the Spanish American war, Katahdin saw no combat and little active service before being sunk as a target off the mouth of the Rappahannock river in 1909.

ay color for camouflage, Polyphemus was an expensive experiment soon overtaken by the technology of rapid fire guns. While the Polyphemus also had torpedoes as a weapon, the USS Katahdin,commissioned in 1893 at a cost of over $900,000 was a pure ram with only light weapons. Painted green to camouflage herself in coastal waters, Katahdin was a harbor defense weapon against invading enemy fleets seeking to shell U.S. cities. Although briefly in commission for the Spanish American war, Katahdin saw no combat and little active service before being sunk as a target off the mouth of the Rappahannock river in 1909.