Alternate History Topic Week

By Christopher Stephens

The United States has been a maritime power since its inception. Maritime trading has always been essential to its economy and over the years has stretched across the globe. Protecting these interests is the job of U.S. Navy. Its origins date back to when North African pirates began seizing American merchant vessels and holding their crews to ransom. This article will explore what could have been if the United States had decided to appease the pirates instead of investing in a national navy to protect its economic interests on the high seas.

The United States had barely stepped on to the global stage, when it faced its first foreign crisis. Its merchant fleets were increasingly coming under attack by North African pirates from the Barbary States. This problem of piracy was hardly new: since the 16th century, European commerce in the Mediterranean had been under threat from the Barbary Nations in North Africa. These states consisted of Tripoli, Algiers, and Tunis, which were nominally protectorates of the Ottoman Empire, along with the independent Sultanate of Morocco. The economies of this region were heavily dependent on piracy and a series of warlords, called Deys, maintained their power largely by bringing in tribute. The European nations had found it easier to simply pay off the pirates rather than engage in sustained military action that would likely forge either temporary peace or require an expensive occupation of North African territory.

American merchant shipping had, in its early years, been protected by European powers: by the British during the colonial period, and during the Revolution later by the French. The onset of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, however, drew attention from the pirate threat in the Mediterranean and left American merchant vessels with European help. Furthermore, upon achieving independence, the fledgling U.S. government found itself short of money. The Continental Navy, which fought during the revolution, was disbanded and the remaining vessels were sold off to raise funds. Unfortunately, this left American merchantmen to fend for themselves on the high seas.

The first U.S. merchant ship was seized in October of 1784 by a Moroccan raider. The crew was held captive for a decade and many wrote letters home describing the deplorable conditions of their imprisonment. The resulting public outcry compelled renewed interest in dealing with this persistent pirate threat.

Dealing between Morocco and the U.S. were not necessarily negative, however. Morocco was the first nation to recognize the United States in 1777 and subsequently signed The Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship in 1786. The other Barbary States were not as easily dealt with. Algiers continued to demand tribute from the U.S. and ransomed captives, although a peace treaty was signed in 1796. The agreement proved very costly for the U.S. (requiring up to 10% of its annual revenue) and military options were increasingly considered. In 1801, Congress approved the construction of six frigates for use in protecting American shipping and compelling the Barbary States to allow American ships to sail the Mediterranean unscathed. Tripoli declared war the same year after its demands for tribute were refused by the newly elected President Thomas Jefferson.

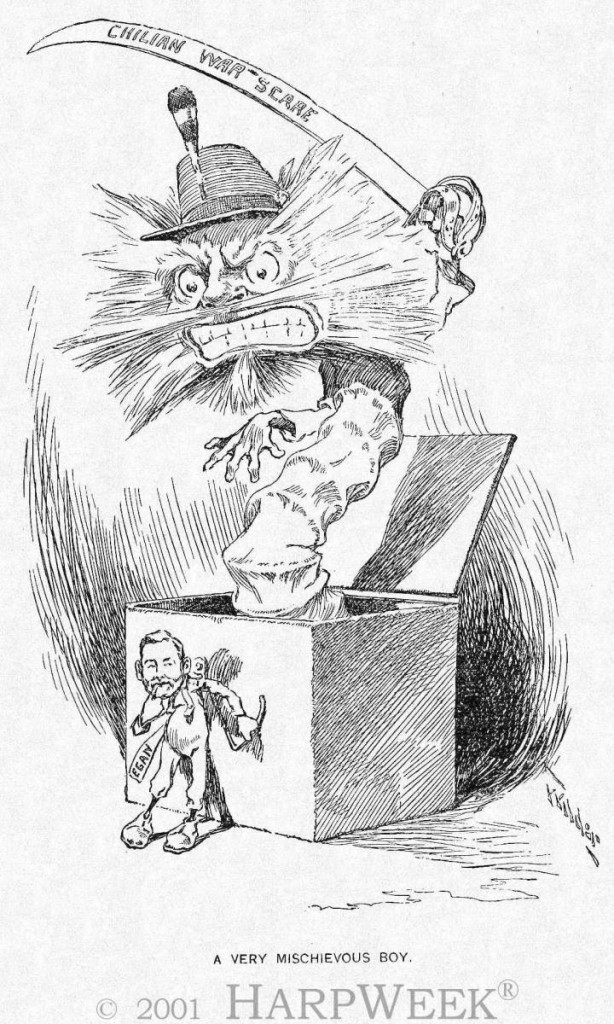

A fleet under the command of Edward Preble was ordered to blockade the port of Tripoli. The expedition was largely successful although losses were taken. The decisive action of the conflict occurred when the former U.S. consul William Eaton led eight U.S. marines and approximately five hundred foreign mercenaries on an overland march to capture the city of Derne, and threatened the capital of Tripoli. The fall of Derne marked the first U.S. victory on foreign soil (and is immortalized in the lyrics of the Marine Corps Hymn). Tripoli subsequently signed a peace treaty with the U.S. in 1805, ending the first Barbary War.

With this first American victory on foreign shores, the Navy demonstrated its ability to project power over long distances and sustain an extended naval campaign away from home ports. In addition, this was the first U.S. Marine landing and subsequent land campaign. The U.S. had demonstrated that it could protect its citizens and could meet any aggressive acts against it with force. In addition, the U.S. was no longer compelled to pay tribute to any foreign nation.

A second Barbary War began when the War of 1812 again drew European attention away from North Africa. Once again U.S. merchant ships were taken by pirates and again the Navy was dispatched to the Mediterranean. In 1815, a fleet under the command of Stephen Decatur won several battles against Algerian pirates and forced Algiers to sign a treaty protecting American vessels from piracy.

Building a navy and launching military expeditions against the Barbary pirates was by no means a unanimous policy decision on the part of the U.S. government, however. Even within Jefferson’s own party, the Democratic-Republicans, there was considerable opposition to the idea of creating a regular navy in the first place. Many prominent Americans were skeptical of creating a centralized standing military because they felt is could be used by rulers to oppress its citizenry. From the Anti-Federalist papers (Brutus X):

“The liberties of a people are in danger from a large standing army, not only because the rulers may employ them for the purposes of supporting themselves in any usurpations of power, which they may see proper to exercise, but there is great hazard, that an army will subvert the forms of the government, under whose authority, they are raised, and establish one, according to the pleasure of their leader.”

Even if the military remained subservient to the state, there were concerns that a standing peacetime military would encourage the government to provoke wars and promote their own agendas that would not be in the best interests of the nation. Still others felt that future of the new United States lay in expanding westward across the continent. Building up a navy, they felt, would allocate resources away from this expansion. In the end, Jefferson and his supporters won out, but it could have easily gone the other way.

Had history followed this alternate course, and the anti-navalists won out, the trajectory of America becoming a world power would have been curtailed. The U.S. would have contended with numerous economic and geopolitical problems. A U.S. Navy would have eventually been created, but not until an event such as the Civil War prompted renewed interest in military expansion. Even then, the resources and expertise would not be in place to accommodate such a policy.

In the meantime, the U.S. would have continued paying tribute to the Barbary States in order to secure safe passage for its merchants, thus straining the national budget. Even if westward expansion became a priority, maritime trade would have remained the economic backbone of the country. In order to continue its overseas trade, the U.S. would be forced to remain reliant on Europe for maritime protection or limit its trade with Europe accordingly and remain a strictly regional power. Instead, America would probably turn its gaze southward to the Spanish colonies in Central and South America. This alliance would almost certainly spark tensions with Britain, France, and even the Dutch, the primary competitors for territory in the Americas. Any number of conflicts could break out, making the War of 1812 look like a border skirmish by comparison.

Alternatively, an agreement could be reached whereby U.S. goods would be transported in European hulls to overseas markets. Such an agreement would deter piracy at the cost of ceding control of the U.S. economic lifeline to foreign powers who could gain immense leverage by threatening to choke it off. While this would have prevented a rising America from coming into coming into conflict with other states, ultimately, this would have the effect of reducing the U.S. to little more than a de facto European colony yet again.

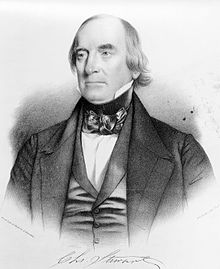

Strategically, policies like the Monroe Doctrine would not be viable for the U.S., given the lack a strong deterrent. Other European competitors would have free access to U.S. waters and generally be able to do as they pleased. Indeed, the Quasi War with France in 1798 and the War of 1812 proved that the U.S. needed a naval force that could stand up to the other European powers. In both cases, the Navy was able to protect American interests at sea. Hiring privateers for protection would be an option for the U.S., though likely an expensive strategy in the long run. In addition, with naval action relegated to secondary importance, it is unlikely that the U.S. would develop the capability to produce homegrown warships. Noted ship designers such as Joshua Humphreys, the designer of the first U.S. frigates, would take their expertise elsewhere, not to mention the great American naval commanders who would remain unknown.

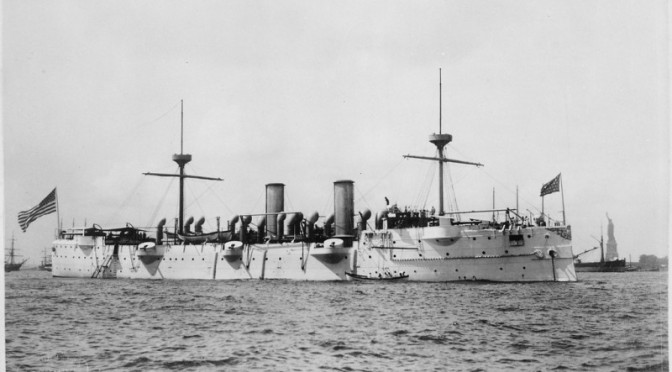

Instead the U.S. began a strong naval tradition of projecting power globally that would manifest itself in the coming decades with the Great White Fleet, the opening of Japan, and the Spanish American war, and continued into the modern era. It is telling, perhaps, that the 2011 Libyan intervention is sometimes referred to the Third Barbary War.

Christopher Stephens is a graduate from the College of William & Mary and is currently with the Project for the Study of the 21st Century. He has formerly completed internships with the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command and the Joint Forces Staff College.

Sources

Ohls, Gary J. Roots of Tradition: Amphibious Warfare in the Early American Republic. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2008

Peskin, Lawrence A. Captives and Countrymen: Barbary Slavery and the American Public, 1785–1816. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009

Tinniswood, Adrian. Pirates of the Barbary: Corsairs, Conquests, and Captivity in the 17th Century Mediterranean. New York: Penguin, 2010.

The Anti-Federalist Papers. Brutus X. January 24, 1788

United States Federal State and Local Government Revenue, Fiscal Year 1800, in $ million, usgovernmentrevenue.com.