India’s Role in the Asia-Pacific Topic Week

By Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan (ret)

With the Indian economy continuing to register arguably the highest rate of growth amongst the major economies of the world and the rise of India as a major reckonable power in her own right, come commensurate levels of international responsibility. As the country’s erstwhile National Security Adviser and ex-Foreign Secretary, Mr. Shiv Shankar Menon, had put it, “sooner rather than later India will have to make real political and military contributions to stability and security in this region that is so critical to our economy and security. What has inhibited us since the Seventies have been limited capabilities and the fact that other States were providers of security in the area. Now that both those limiting factors are changing, our approach and behaviour should change in defence of our interests.”[1]

India is actively pursuing and promoting the ‘blueing’ of her burgeoning ocean economy, with her trade to GDP Ratio (Openness Index) recording a decadal average of 40%. The Prime Minister’s firm declaration of national intent for India to be a net security-provider in the Indian Ocean and beyond, means the various connotations of maritime security (defined as freedom from threats emanating ‘in’, ‘from’, or ‘through’ the medium of the sea[2]) can no longer be denied centrality in any serious consideration of India’s national security.

India’s requirement to ensure stability in her maritime neighborhood underpins her acceptance of this role of providing net security. This need for regional stability is informed by a number of reliable studies[3] that show political instability in one’s neighboring countries has a powerful and frequently adverse effect upon one’s own national economy. The magnitude of this effect is similar to that of an equivalent rise in domestic political instability in one’s own country. This negative effect is felt through a number of channels of inter-State commercial interaction. Amongst the principal ones are ‘space-time-and-cost’ disruptions of external trade. These, in turn, affect domestic manufacturing and local consumption and hence, money-flows and market-dynamism. Another is the sharp spurt in military expenditure and outlays as mitigating mechanisms against one’s own country being ‘infected’ by the malaise of instability affecting one or more neighboring or proximate countries. Likewise, increased uncertainty and risk dissuades overseas business-investment[4] as well as physical capital accumulation, not limited to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) alone. Tourism, which is an important source of revenue and economic buoyancy for many island nations in the Indian Ocean, is similarly adversely affected by catalysts of regional instability — an increased threat of piracy, for example. Indeed, there is “strong empirical support for the proposition that a country’s growth rate depends not only on domestic investment but also on the investment of its neighbouring countries”[5].

In fact, there is growing clarity within New Delhi’s corridors of power that, as Zoltan Merszei famously said, “Money is a coward. Investment capital will not flow down a hazardous, unlit street where the risk is visibly higher than the potential reward[6].” The Business Dictionary defines ‘Risk’ as “the probability of loss inherent in financing methods, which may impair the ability to provide adequate return”[7]. In geopolitical terms, risk may be considered to be the probability of occurrence of an event factored against the degree of loss that is anticipated, should the event occur. In the context of this discussion, I hold that money does not go where there is excessive politico-military uncertainty, since such a condition defines excessive risk.

The 2011 edition of the ‘World Development Report,’ which focused specifically upon conflict, security, and development, emphasizes that violent conflict was undoubtedly one of the biggest drivers of poverty in the developing world[8]. One of the biggest risks for developing countries, it argued, was that of being caught in a ‘conflict trap’ — a vicious circle whereby poverty stokes conflicts, and conflict in turn increases poverty. With the weight of evidence that links regional instability to low economic growth in all nations in the near proximity of the politico-militarily unstable one, and recalling that the core national interest of India is to assure and ensure the material, economic, and societal well-being of the people of India, ensuring stability in her maritime neighborhood is quite clearly a major national imperative.

It is this requirement for regional stability that provides the context of India being perceived — both externally and, increasingly, internally as well — as a net provider of security in the Indian Ocean and beyond. Perhaps the first time that such a sentiment was formally expressed on an international stage was at the 2009 edition of the “Shangri La Dialogue” organized annually in Singapore by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), wherein Mr. Robert Gates, who was then Secretary of Defesce of the United States, said, “We look to India to be a partner and net provider of security in the Indian Ocean and beyond….”[9]. This was repeated in the 2010 edition of the “Quadrennial Defense Review” of the USA, which emphasized, “….as its military capabilities grow, India will contribute to Asia as a net provider of security in the Indian Ocean and beyond.”[10] However, the most categoric and unequivocal declaration of this intent occurred at no less than the Prime Ministerial level, when the erstwhile Prime Minister of India, Dr. Manmohan Singh said — “…We live in a difficult neighborhood, which holds the full range of conventional, strategic, and non-traditional challenges ……….. Our defense cooperation has grown and today we have unprecedented access to high technology, capital, and partnerships. We have also sought to assume our responsibility for stability in the Indian Ocean Region. We are well positioned, therefore, to become a net provider of security in our immediate region and beyond…”[11].

The opportunity is clearly recognized [12] and the apex level of political signalling seems sufficient. And yet, one continues to encounter misgivings about whether India has the military capability to play the role of a net security provider for the region. These are largely remnants of a half century of muddled thinking[13] that viewed ‘security’ only in terms of the defense of territory within a state system whose defining characteristic was an incessant competition for military superiority with other nation-states, all lying within a classic state of anarchy without superior or governing authority. Yet, for most people of the world, threats to individual security, such as disease, hunger, inadequate or unsafe water, environmental contamination, crime, etc., remain far more immediate and significant. Thus, as nation-states such as India begin to incorporate the many facets of ‘Human Security,’ they find themselves moving away from the earlier, excessively narrow definition. Consequently, new terms such as ‘Non-Traditional Security’ and ‘Human Security,’ drawn from the 1994 Report of the UNDP[14], have made their way into our contemporary security lexicon and established themselves within our individual and collective security consciousness. Apart from ‘Military Security’ which does, of course, continue to enjoy primacy in a world system defined by sovereign nation-states, the UNDP lists as many as seven components of Human Security: Economic Security, Food Security, Health Security, Environmental Security, Personal Security, Community Security, and, Political Security[15].

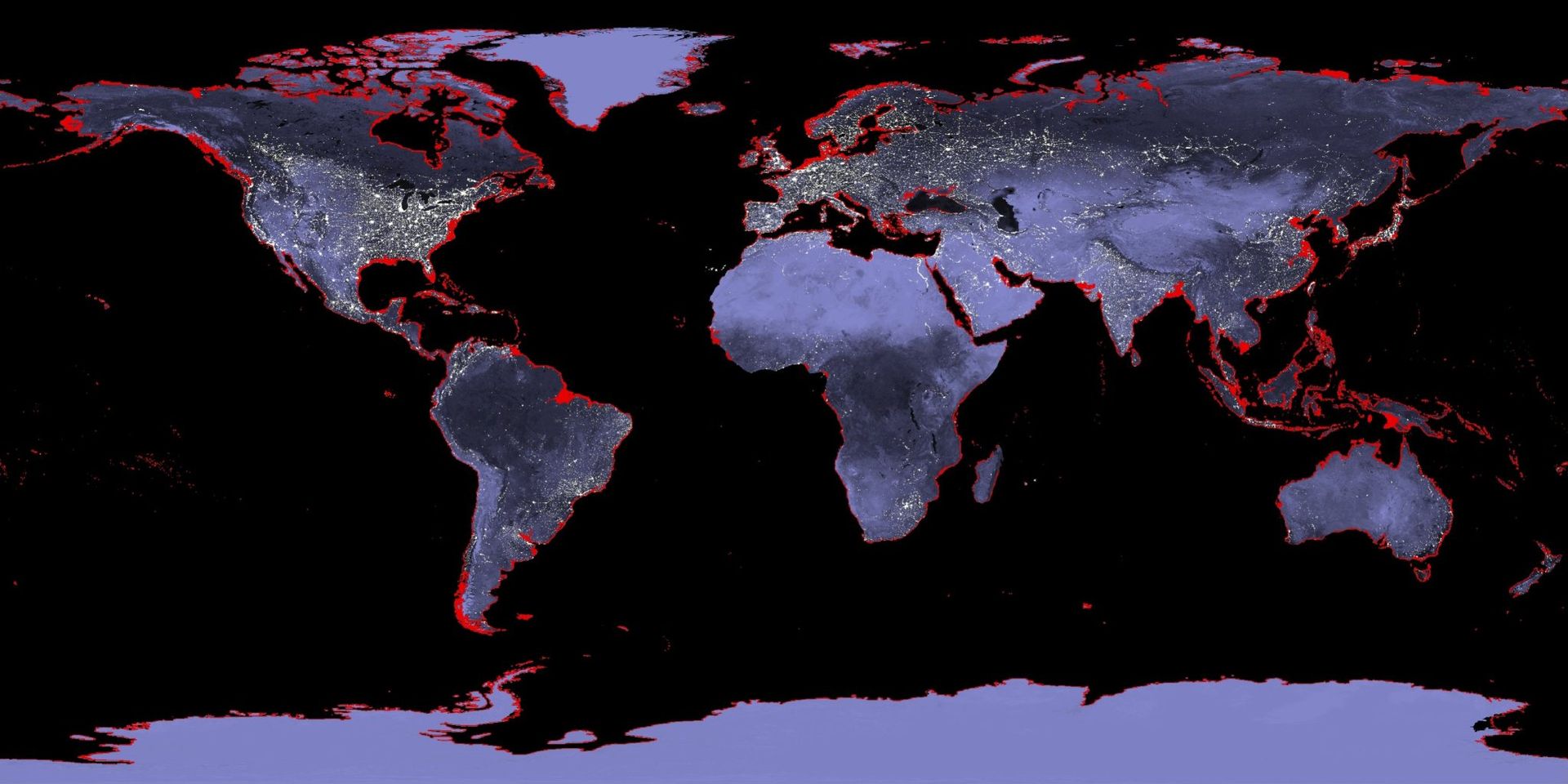

Threats arising from a lack of maritime security could be faced by individuals themselves or by one or more of the levels by which individuals organize into societies and into nation-states. They could arise from natural causes or from manmade ones, or from the interplay of one with the other, as in the case of environmental degradation, or, global warming. Indeed, there is a growing realization that climate change has a very significant security dimension that impacts us at the national, regional, and global levels — and, going in the other direction, at subnational and human (individual) ones. As Sir David King, the UK Foreign Secretary’s Special Representative for Climate Change, points out, “A growing body of credible, empirical evidence has emerged over the past decade to show that the climate change that has occurred thus far – involving an increase of 0.8°C in global average temperatures – is already influencing dynamics associated with human, sub-national, national and international security”[16]. Perhaps even more disconcerting is the ease with which the various security impacts of climate change transcend the traditional stove-piping of internal and external security.

For instance, as rising global temperatures create enhanced heat and water stress, agricultural failures at a national level are very likely across entire regions. The probability is high that substantially lowered levels of food security will result in human migration, in turn causing a whole slew of ills ranging from a sharp increase in ‘barbarism’ to demographic shifts. The Syrian unrest — and the consequent rise of the ISIL/ISIS/Daesh[17] as a transnational threat — offers an illustrative case. The West Asian, the North African, and the Mediterranean regions have all being experiencing a drying trend over the last few decades, with a notable decline in winter precipitation — in conformity with the forecasts that had already been made by climate-modelling.[18] As a consequence of the extreme drought suffered by Syria between 2007 and 2011, involving severe and widespread crop-failure and the loss of livestock, there was a mass internal displacement of some two million farmers and herders into urban areas that were already stressed with Iraqi and Palestinian refugees. By 2011, around a million Syrians faced extreme food insecurity and another three million had been driven into extreme poverty[19]. While several factors — such as political insensitivity, a lack of democratic mechanisms for the venting of public frustration and brutal State repression — drove the political unrest and conflict that followed (and contributed to the appeal of the ISIL/ISIS/Daesh), it is difficult to pretend that this widespread impoverishment and large-scale displacement — which was a result of climate change — did not play a major role[20].

Today, threats to human security, such as religious extremism; international terrorism; drug and arms smuggling; demographic shifts — whether caused by migration or by other factors; human trafficking; environmental degradation; energy, food and water shortages; all figure prominently as threats that are increasingly inseparable from military ones. Likewise, the linkages between ‘external’ and ‘internal’ threats arising from the impact of climate change are clearly discernible in the maritime space as well. For instance, the Republic of the Maldives is located a mere 250 nm south-west of India. Its constituent islands and atolls have an average elevation above the current Mean Sea Level of just five feet (the highest elevation is a mere eight feet!). Thus, it is extremely susceptible to a rise in sea levels because of global warming. The 5th Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), predicts that in a ‘high emissions’ scenario, there will be a global rise by 52-98 cm (20.47 to 36.22 inches) by the year 2100[21]. Even with a regime of aggressive reduction in emissions, a rise by 28-61 cm (11 to 24 inches) is predicted and this could be disastrous for Maldives — its population is about 336,000 people, many or all of whom could suddenly become ‘boat people!’ Where will they all go? Probably to India! Clearly, India needs to have multi-dimensional contingency plans in place to deal with the obvious security implications of the unfolding of such a scenario.

Such realizations are leading Indian security-planners to embrace concepts such as ‘cooperative’ instead of ‘competitive’ security and ‘comprehensive’ rather than merely ‘military’ security. These are the very concepts that constitute the foundation of India’s ability and willingness to be a net security-provider in the Indian Ocean and beyond. This ability is premised not so much upon India’s arguable capacity by way of material wherewithal, but instead, upon India’s widely acknowledged and impressive capability — organisation, training, operational and maintenance philosophies, procedures, practices, etc. It is important to differentiate between ‘Capacity-building’ and ‘Capability-enhancement.’ Capacity-Building is most often used in the context of material wherewithal — i.e., the provision of hardware. This could include platforms, infrastructure, equipment, or spares, any or all of which might be provided to entities that have a need to develop a certain capacity to undertake one or more maritime (or naval) role.

For example, when the coastal police are given shallow-draft patrol boats with which to carry out patrols in coastal waters, this would constitute capacity-building. ‘Capability Enhancement’ on the other hand, refers to the realization of a potential aptitude or ability. In a maritime context, it implies that the potential recipient already has the capacity (or some proportion of it) to undertake a naval/maritime role, and further inputs will now enhance his existing capability to exploit the material wherewithal so as to derive better results. Capability-enhancement is mostly by way of intangibles and cognitive processes. To continue with the example of the coastal police, the provision of patrol-boats would have built some reasonable capacity. However, once the coastal police imbibe the various methods, procedures and processes that will enable them to logistically-support, maintain, repair, and operationally deploy these boats, their capability in terms of coastal patrolling would have been enhanced. Likewise, a certain navy (or maritime-security force) may well possess operationally viable sea-going Offshore Patrol-Vessels (OPVs). This would be capacity. On the other hand, if the crew aboard the OPV in question did not know how to distinguish between, say, a ‘demersal’ trawler (one designed to catch fish that live close to the seabed) and a ‘pelagic’ trawler (one designed to catch fish that swim close to the surface of the sea), it might be unable to establish ‘suspicious’ behavior as a function of the depth of water in which it is operating. When India provided the Tarmugli (now renamed PS Topaz) and the Tarasa (now renamed PS Constant) to Seychelles, India was engaging in capacity-building. However, the ‘planned preventive maintenance’ needed to sustain these ships in an operational state might well require additional ‘capability-enhancement’ inputs from India by way of maintenance-philosophies, maintenance-schedules, technical-training, etc.

There is considerable evidence that India is, indeed, rising to the occasion. Examples of regional capacity-building are the provision (against generous Lines of Credit) of patrol vessels, short/medium-range maritime patrol aircraft, coastal surveillance radars, shore-based AIS Stations, spares, etc., to several of India’s maritime neighbors. Recipients include Sri Lanka, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Regional capability-enhancement by India is extremely vigorous. This incorporates, inter-alia, infrastructure-development such as the setting-up of an afloat-support organisation for ships and patrol craft, the creation of a dockyard in Maldives, airfield development and allied support facilities in Mauritius, and a wide variety of maritime training — in India as well as in-country training by Indian training-teams. It also includes the conduct of extensive hydrographic surveys by specialized Indian ships and aircraft. Indian ships and aircraft make a major effort in regional surface and airborne EEZ-surveillance to counter maritime crime such as illegal immigration, human-trafficking, Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing, and piracy. Beneficiaries once again include vulnerable Indian Ocean nation-states such as Sri Lanka, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles, Myanmar, Vietnam, etc.

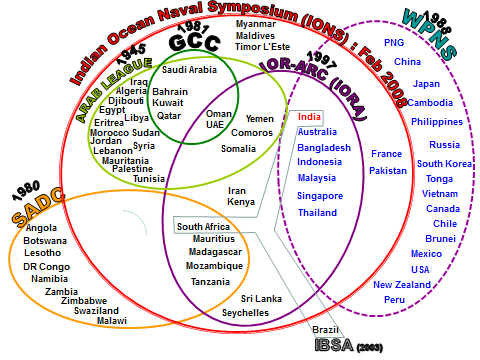

A critical success in India’s regional endeavors has been the creation of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS). IONS is the current century’s first (and to date the only) robust and inclusive regional maritime-security organizational structure within the Indian Ocean. It was launched by New Delhi in 2008 with active participation of very nearly all 37 littoral nations of the Indian Ocean region at the level of their respective Chiefs of Navy/Heads of national maritime forces. It is broadly modeled upon the Western Pacific Naval Symposium (WPNS) and has gained impressive traction over the past eight years. Its inclusiveness is evident from the fact that both India and Pakistan — often associated with being arch rivals and even spoilers, at times — are active and enthusiastic members. For the moment, suffice to say that it represents a unique opportunity to progress common responses to common regional threats.

Indeed, the current and future maritime plans and processes through which India can translate this statement of intent into tangible reality lie at the core of India’s willingness to be a net security-provider.

Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan (ret.) retired as Commandant of the Indian Naval Academy at Ezhimala. An alumnus of the prestigious National Defence College.

[1] Shiv Shankar Menon; “We Must Now Choose”; lecture on “India’s Changing Geopolitical Environment” at the ‘Changing Asia’ series of Lectures, New Delhi, 23 Jan 2016, available at url: http://www.outlookindia.com/article/we-must-now-choose/296484

[2] Address by Dr Manmohan Singh, Prime Minister of India, inaugurating the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) Seminar at New Delhi, 14 February, 2008; available at url: http://archivepmo.nic.in/drmanmohansingh/speech-details.php?nodeid=633

[3] Alberto Ades, (Goldman, Sachs & Co) and Hak B Chua (Malaysian Management Institute); “Thy Neighbour’s Curse: Regional Instability and Economic Growth”. JSTOR: Journal of Economic Growth, Vol 2, No 3, (Sep. 97), pp 279-304; available at url: http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/40215960?uid=3738256&uid=2134&uid=2483820223&uid=2&uid=70&uid=3&uid=2483820213&uid=60&sid=21104638501903

[4] Ari Aisen and Francisco Veiga; “How Does Political Instability Affect Economic Growth?”; IMF (Middle East and Central Asia Department) Working Paper, January 2011.

[5] Hak B Chua; “Regional Spillovers and Economic Growth“. Yale University, Economic Growth Center, September 1993

[6] Zoltan Merszei; speech at the Empire Club of Canada on 16 February, 1978; available at url: http://speeches.empireclub.org/61635/data?n=2 (accessed on 18 May 2014)

[7] http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/financial-risk.html (accessed on 18 May 214)

[8] http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/WDR2011_Full_Text.pdf (accessed on 18 May 214)

[9] Dr Robert Gates; “America’s security role in the Asia–Pacific”; The IISS Shangri-La Dialogue: 14th Asia Security Summit; 30 May 2009; available at url: http://www.iiss.org/en/events/shangri%20la%20dialogue/archive/shangri-la-dialogue-2009-99ea/first-plenary-session-5080/dr-robert-gates-6609 (accessed on 07 August 2015)

[10] “Quadrennial Defense Review Report”, Department of Defense, United States of America; February 2010; p.60

[11] Press Information Bureau, Government Of India (Prime Minister’s Office); “PM’s speech at the Foundation Stone Laying Ceremony for the Indian National Defence University at Gurgaon”, 23-May, 2013; available at url: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/mbErel.aspx?relid=96146 (accessed on 07 August 2015)

[12] Shivshankar Menon; “India in the 21st century World”; Address at the Indian Association of Foreign Affairs Correspondents (IAFAC); 13 February 2014; available at url: http://www.irgamag.com/resources/interviews-documents/item/7409-india-in-the-21st-century-world (accessed on 10 Aug 15)

[13] In April 1968, the then Minister of state for External Affairs, Mr B R Bhagat, told the Indian Parliament: “… If we dispersed our efforts and took on responsibilities that we are not capable of shouldering, it would not only weaken our own defence but would create a false sense of security and might even provoke a greater tension in this area.”

[14] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); “Human Development Report, 1994”; Oxford University Press, 1994; available at url: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/255/hdr_1994_en_complete_nostats.pdf (accessed on 08 August 2015)

See also:

Oscar A Gómez and Des Gasper; “Human Security”; United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report Office, available at url: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/human_security_guidance_note_r-nhdrs.pdf (accessed on 08 August 2015)

[15] UNDP “Human Development Report, 1994”, Op Cit; p. 24

[16] David King, Daniel Schrag, Zhou Dadi, Qi Ye and Arunabha Ghosh; Report on “Climate Change: A Risk Assessment”, Ed. James Hynard and Tom Rodger; Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP) [University of Cambridge, UK], Commissioned by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office; p. 120

[17] ISIL: Islamic State of Syria in the Levant = ISIS: Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (also sometimes expanded to Islamic State of Syria and al-Sham) = Daesh (an Arabic acronym formed from the initial letters of the group’s previous name in Arabic: “al-Dawla al-Islamiya fil Iraq wa al-Sham”, where ‘al-Sham’ was commonly used during the rule of the Muslim Caliphs from the 7th Century to describe the area between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates, Anatolia [in present day Turkey] and Egypt).

See: Faisal Irshaid; “ISIS, ISIL, IS or Daesh? One Group, Many Names”; BBC Monitoring, 02 December 2015; available at url: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27994277

[18] Hoerling et al. (2012); “On the Increased Frequency of Mediterranean Drought”, Journal of the American Meteorological Society; (See also NOAA [ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] Press Release “NOAA Study: Human-caused Climate Change a Major Factor in More Frequent Mediterranean Droughts”’ October 27, 2011; available at url: http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2011/20111027_drought.html

[19] CP Kelley, Shahrzad M Mohtadi, MA Cane, R Seager and Y Kushnir (2015); “Climate Change in the Fertile Crescent and Implications of the Recent Syrian Drought”; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 11, pp. 3241-3246

[20] F Femia and C Werrell; ‘Syria: Climate Change, Drought and Social Unrest”; The Center for Climate and Security; available at url: http://climateandsecurity.org/2012/02/29/syria-climate-change-drought-and-social-unrest/

[21] Chapter 13 of ‘Working Group 1’ Contribution to the 5th IPCC Report; available at url: https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg1/WG1AR5_Chapter13_FINAL.pdf