By Ryan Belscamper

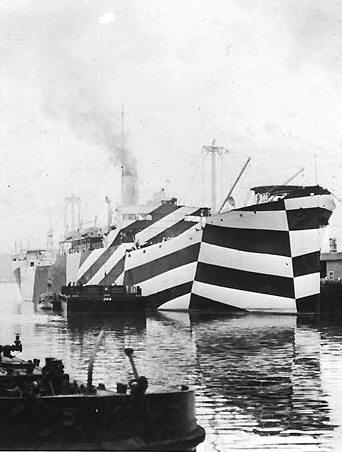

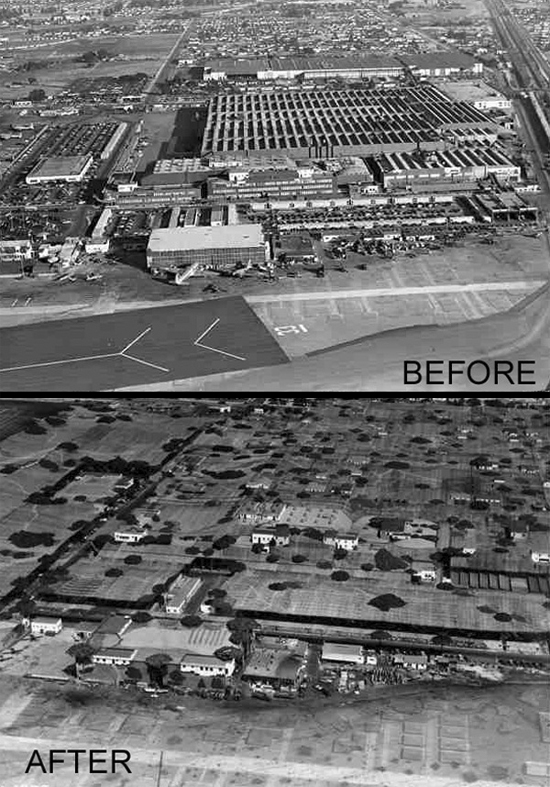

Seven years ago, the Marine Corps decided they needed a better way to “Kick in doors on foreign shores!” Landing craft were slow and vulnerable, aircraft weren’t as slow, but still pretty vulnerable, and the ships to launch either one of them would not survive for long operating nearby. Shore bombardment was a problem, too. How do you provide enough firepower when you don’t have enough ships? Hitting the beach was only the first insurmountable problem. Once there, Marines would need to fight further inshore, using who knows what for supply lines, and only the equipment that could have been landed in the first place. If someone could just get a foot in the door, take an airfield or knock out local defenses, then more traditional methods could handle everything else. If victory could be won fast enough, then resources might go far enough. That’s where really bad ideas started sounding like good ideas.

_______________________________________

Two years ago, Jennings had been on a patrol in Afghanistan when they’d come under attack. Half the squad was dead or wounded in the first two seconds, the other half fighting for their lives. Reinforcement took four minutes to arrive, and the fight didn’t last long after that. For those four minutes though, Jennings was in a special place. There was no panic, no pain, no fear or loss. For four minutes, Jennings just did his job. Bullets couldn’t touch him, and he couldn’t miss. Two grenades over there, one more to the left. Grab more from McBride, he wasn’t going to use them. Grab an extra magazine while he was at it, and shoot that guy on the right. Combat was supposed to be terrifying, but this was just shooting things.

Afterward, Colonel Walks told Jennings he’d fought well, and asked if he wanted to avoid pulling guard or patrol duty ever again. That sounded pretty unlikely, so Jennings asked what the catch was.

“The catch is, all you’ll ever do again is either train or fight. New unit, handpicked, volunteer only, and you have to get shot at to join.” the Colonel explained. “Today, you got shot at.”

To Jennings, training was fun, sitting in barracks dull, guard duty was awful, patrol duty was torture, and combat was just shooting things. So he said “Yes, sir.” That evening, he was in the back of a C-17, heading stateside.

35 Marines made up the new unit. Five squads, seven Marines to a squad, plus a Major everyone called Brickhead, because the man looked like a brick. Seven was a peculiar number to make up a squad, but apparently that was all their new transports could fit. Not that Jennings or any of the other members of his unit got to see those transports yet.

For the next two years, Jennings and the others trained. They trained to enter and clear buildings, and they trained to fight in the mud. They trained as teams, then they trained to fight alone. They got new weapons, new armor, and a fancy new helmet that would show where everyone else was at. The Major called their gear a three-piece suit, though it looked nothing like a suit to Jennings. They spent a lot of time in the weight room, and more time in the ‘Rattle Room.’ The rattle room looked like one of those high-end flight simulators, the kind that move around on pneumatic pistons. This one was all about shaking a squad up, then stopping suddenly to see how fast they could recover.

No-one knew what to call their new unit. It was clearly a platoon, but a platoon of what? They’d eventually been allowed to pick their own names for squads. Someone in Jennings’ squad thought their new armor looked like an armadillo, and the name stuck. Growing up in east Texas, they looked nothing like armadillos to Jennings. Five of second squad’s seven original members were female, so Kline and Phillips just had to live with being called “She-Devils.” Jennings had seen them train, so he thought She-Devils was perhaps a bit too tame. “Vicious Amazonian terror fiends rage killing everything” was a bit unwieldy though. Kicking in doors was exactly what this whole unit was about, so calling themselves “Door-Kickers” made sense. Hedgehogs made about as much sense as Armadillos. Butterflies was a complete mystery, but it wasn’t excessively vulgar or obscene, so it stood. Other units on base supplied the platoon name by always complaining how Brickhead’s men never pulled guard duty. They weren’t a platoon, or a company, or a brigade. They were “Brickheads.” Jennings was now a Brickhead.

_______________________________________

“One-way in 30 minutes!” Sitting in the berthing compartment, Brickhead was briefing them on what would be their first operational mission. A Navy special warfare pin painted on one wall revealed the compartment’s usual occupants. Given a little paint, the Brickheads would’ve gladly replaced the Trident with a Globe. Two weeks stuck underwater gave them more than enough time. The slide showed a map of a small island with an airfield. “Armadillos, She-Devils, and Door-Kickers are hitting the north side of the island. Hedgehogs and Butterflies in the south.”

“Armadillos, we’re going down the west shore. Our job is to neutralize the airfield. Nothing takes off once we hit. She-Devils, you’re in the middle. Take down the control tower and main barracks. Door-Kickers, you’re on the east shore. This tower has the island’s main search radar, and this building is the operations center. Level them both.”

“Hedgehogs will come up the west shore from the south, taking out these missile sites. Butterflies will be coming up the eastern shore and taking out that marina. We don’t need to deal with any patrol boats.” Yellow boxes were drawn around each major objective. Both the map and the boxes would appear on a display inside each Marine’s helmet. As objectives were assessed as either destroyed or neutralized, the yellow symbols would change to black. Blue circles would indicate each other’s positions, while red diamonds would relay enemy positions. A built-in radio would allow them to stay in constant contact with their squad and with the platoon.

While the Major continued, Jennings focused on his armor. Patrol had always sucked, lugging around 50 pounds of gear. Right now, Jennings was bolting on the last of about 120 pounds of armor. With a powered exoskeleton, it felt like about ten. Of course, that would only help for the first few minutes. After that, the armor would feel like about 40 pounds, and eventually he’d have to pull the cord that would shed both the exoskeleton and 90 pounds of his armor. Batteries only lasted so long, ten minutes, give or take. His weapon fired 12mm armor piercing sabots, with an underslung launcher firing up to nine 40mm smart grenades. Each member of the squad also carried four rockets, good to about 300 meters. They’d take the back off a tank, supposedly, if you could get behind one. The last two weapons seemed almost like a joke: a demolition charge about a foot across and three inches thick with foam glue on the dangerous side, and a combat knife that any sane person would call a sword. Just in case you needed to kill buildings or fight the Roman Army.

No one ever said the next part was a good idea. Actually, quite a lot of people had said it was a bad one. But apparently, somebody thought strapping a handful of Marines to the top of a ballistic missile wasn’t that bad of an idea, because Jennings was about to do just that, along with the rest of the Brickheads.

The Armadillos, She-devils, and Doorkickers filed out of the small berthing compartment onboard the converted ballistic missile submarine, into the missile room, through small hatches near the top of each missile tube, and into their deployment pods atop the repurposed missiles. The Hedgehogs and Butterflies would be doing the same aboard another sub somewhere. The corpsmen passed out Dramamine while boson-mates turned armor-techs literally bolted the armored warriors into place. The hatches were sealed, and then nothing happened.

“You sure this thing has room for seven?”

“Why, you don’t like my company?”

“Mom! He’s touching me!”

“No, I don’t like your elbow in my back.”

“That’s not my elbow.”

Laughter.

“How long is this flight supposed to be?” someone else chattered.

“About 500 miles.”

“So, is there a movie?”

More laughter.

Brickhead cut in on the banter, “Combat in eight minutes, jokers.”

One minute, 37 seconds later, something big kicked Jennings in the back. After the initial kick, he was falling backwards for about a second, before the rocket motor kicked in. Obviously, it was the rocket motor because Jennings’ teeth were rattling out and the kick became one continuous shove. At least this was the worst part.

Two minutes later, and the worst part was over. Now Jennings was in free fall and knew why the docs had passed out the Dramamine. His display read four minutes sixteen seconds to landing. Three arcs rose from the map, showing where each squad was rising from the ocean. Two more arcs began rising from the south. Three minutes. Two minutes. At a minute and a half, plummeting back into atmosphere, Jennings learned two things. The first was that he was wrong about launch being the worst part. The second was why those Rattle-Room operators had always tossed them around so much. He was a rag-doll in the hands of an insane child. If he could have moved, he’d have broken every limb flailing about. Things were breaking off the capsule, up and down were alien concepts, the display was a riot of lines and colors, and something went missing. His display changed to an overlay of the island, with a timer counting down from thirty. The violent jolting eased, as the capsule dropped just below Mach five in its descent. At 27 seconds, Jennings again learned he was wrong about the worst part. Retrorockets fired, crushing Jennings in his armor. The pod flew apart around him, bolts released, the ground came with a thump, and he was face down in the sand.

_______________________________________

Jennings could feel the warmth of the coral sand beneath him. Rolling onto his back, he could just barely feel the tropical breeze under his armor. He sat up in the sand, enjoying the peace and quiet, not entirely certain how he got there. The sea lapped at the shoreline a few dozen feet away, while acrid smoke drifted by from the left. He could hear some voices, and off in the far distance there was a staccato popping sound. Looking to his right, Jennings could see the sun just cresting some low, ugly buildings sporting radio towers. Something about the size of a surfboard impaled the sand nearby. To his left was a smoking, hollowed out cone about ten feet high. Why did that voice sound so urgent? And what was that sputtering in the sand all around him?

“JENNINGS! GET YOUR HEAD IN THE GAME!” Brickhead screamed. “She-Devils are out. Ajax, we’re getting shot at, you wanna do something about that? Flores, Young, take the shore defense. Jennings, Chavez, control tower! Hamlet, you’re with me. Let’s wreck that flight line before anything leaves this island!”

Jennings remembered where he was. This was a hostile island with 500 enemy soldiers and 35 of his own unit trying to take the whole thing out. Scratch that, She-Devils were out? So, 28 against 500. Great. Rolling and turning he got to his knees, then to his feet. He began running. The sputtering in the nearby sand turned to a tapping on his armor as Jennings realized he was being shot at. With a terrific ripping sound, first one, then three rockets launched from the squad behind him. A short tower with a point defense weapon atop it exploded on one side, while other things went crack and boom behind him. Another pair of rockets, one each from Jennings and Chavez into the barricades ahead and the tapping stopped. Spotting one of the island’s cruise missile launchers, he let off a second rocket.

Jennings saw the island’s radar turn to shrapnel and wreckage as a rocket from the Door-Kickers hit. His display didn’t change the objective from yellow to black. None of the other Brickheads appeared on his display either. As Jennings and Chavez approached the control tower, they spotted a number of enemy soldiers improvising a second defensive position. What were they called again? People’s Soldiers? Revolutionary Marines? Freedom Militia? It didn’t matter, Chavez put a rocket into the position, and Jennings set three grenades to go off just above and behind the barricades that might have saved someone from the rocket. They continued their charge to the tower.

Reaching the back of the tower, the two Brickheads rested for a half-second. The door was not on this side, so they would need to circle the building to find an entrance. Their comms were filled with static, so Chavez pointed first at Jennings, then the corner on their left. Chavez turned and went for the right. As Jennings stepped around the corner he spotted the heavy machine gun waiting for him. He leapt back, barely getting clear before bullets began tearing at the concrete and the air in front of him. Chavez wasn’t so lucky rounding the other side of the building. They wore a lot of armor, and at longer range, laying prone, the bullets might have deflected off. At less than forty feet, catching fire right in the chest, Chavez didn’t have much chance. Jennings bounced three grenades around the corner, then turned to help Chavez. Reaching her ankle, he dragged her behind the building before lobbing three more grenades into that alley. A handful of pockmarks showed where the armor had actually worked, but one furrow dug into the armor showed where a bullet had slid up the chest plate and under her helmet.

Jennings grabbed the demo charge from Chavez’s side, and slapped it onto the wall. He moved as far toward one alley as he dared, stepping back from the wall and crouching as the charge went off. Shaped charge explosives make a heck of a hole in one direction, but still blow a lot of shrapnel out to the sides as well. Jennings avoided most of it by not being in plane with the charge, but his armor still rattled with what he did catch. Jumping to his feet, Jennings dove through the door he had just made. Pulling down two display cases, he blocked the front door. Shoving a flagstaff through the push bar secured it just a little better. After that, he found the stairs.

Reaching the control room, he shot the two guards. An officer of some type still had his sidearm holstered. The officer reached for his weapon, struggling to get it clear, and stopped as he realized the futility of his situation. Jennings took two steps, punching the man in the face with an armored fist. The officer dropped to the floor, unconscious. The horrified controllers in the room broke and ran when Jennings started shouting at them and chasing them with his knife. It was one way to clear a room, and probably faster than shooting everyone. Down the stairs, he could hear revolutionary soldiers or whatever they were called trying to break through the front door. No time to do things neatly, Jennings shot every console and equipment box he saw, smashing two handheld radios to the ground.

Turning back to the stairs, he found the first enemy just reaching the control room. The same exoskeleton that made it possible to run and fight wearing so much armor made a kick to the chest an unstoppable force. Sending the man back down the stairs with two of his buddies, Jennings grabbed a desk and shoved it onto the stairs behind them. While he waited for something to go wrong, he looked out the windows at the island below.

The northern half of the flight line was a smoking wreck, and two fighter-bombers littered the taxiway. Brickhead and Hamlet were doing their job well. A helicopter tried to lift off behind them, flames shooting from the engine compartment before the craft was engulfed in a fireball. The wreckage landed on the runway, blocking its use. To the south, Jennings could see the Butterflies and Hedgehogs working their way north, about a mile distant. Three patrol boats had made it out of the marina and were beginning to shell the Butterflies with grenades and rocket fire. One of the patrol boats exploded as it was hit by a rocket, but the other two kept firing. Surface-to-air missile launchers were elevated on the western shore, but began exploding as the Hedgehogs got close enough to them. One missile launched, then exploded in mid-air. Another spiraled into the sea, holes punched through its guidance systems. Just below, Jennings could see the barracks on fire and partially collapsed. The armory was in worse shape, having taken five or more rocket hits. A radio mast collapsed, and Jennings’ display flickered to life. The operations center appeared to still be intact, so Jennings decided to go there next. Yelling and banging behind him told Jennings his makeshift barricade was at an end.

Moving sluggishly, he realized his batteries were beginning to run low. He checked his ammunition: two magazines with 25 rounds each, no grenades, two rockets, and a demolition charge. And one knife. He put five rounds through the desk to clear the top of the stairs, then pulled it aside. Seeing men coming around the landing, he slid feet first down the stairs, using his armor as a sled and his boots as a battering ram. Bringing out his knife, he dispatched the men who broke his fall. One flight down, four to go, and he’d be outside again. Repeating his armor sled trick, he almost made it. On the last step, the soldier he aimed for managed to jump aside. While Jennings was on the ground, three more jumped on him, pinning his now unpowered form to the ground. His display showed lines of red diamonds all over the island, as the defenders managed to regroup. Eight blue circles remained, all of them surrounded by red. Everyone else had either died or taken their armor off. The good news was that all of the yellow was gone.

His captors didn’t need much time to find the release for his armor as they stripped him of his equipment. With one arm twisted so far behind his back Jennings thought they were trying to break it, he was marched outside toward the flight line. Smoke and a strange buzzing noise filled the air. Distant crunches told of fighting continuing to the south. He looked around, finding a disappointing number of buildings still undamaged. He was punched in the head, and his arm was lifted forcing Jennings to march doubled over as the buzzing grew louder. No more sight-seeing.

The gentle sea breeze erupted into a hurricane, the buzzing replaced by an enormous rush of air and sand. His captors scattered as an aircraft swooped overhead, dropping almost right on top of them. Another landed next to it, while a third circled overhead. Gunfire erupted as Marines poured from the aircraft, running past him. The two Ospreys leapt back into the air, the third dropping to unload its precious cargo. More shouts, then deafening roars as LCACs pulled onto the runway. Landing Craft, Air Cushion; they looked more like metal storage buildings drifting to a stop before sitting on the ground to release armored vehicles from within. Fighting vehicles and armored trucks rolled into the spaces between the various buildings, forming instant bunkers and strongpoints. They were too close to the buildings to protect themselves from rockets or grenades, but those buildings were already being swarmed by infantry. Jennings couldn’t count the aircraft suddenly overhead, but there were plenty.

_______________________________________

The Ospreys and the LCACs had been timed to arrive just after the Brickheads had done their work. By knocking the island’s radar out, grounding planes, ruining air and shore defenses, they’d made the island defenseless. With so much mayhem from the Brickheads, no one had even seen the assault craft. In less than 15 minutes the arriving Marines had secured every building, made prisoners of everyone still moving on the island, and begun setting up their own equipment. After 20 minutes everyone dove for cover when reports came in of enemy aircraft approaching. Five minutes after that it was back to work, apparently they weren’t coming after all. An hour after his own landing, Jennings was regrouped with the other surviving Brickheads, including the Major.

Within another hour, a second landing arrived, bringing a mobile radar station, surface to air missiles, and Seabees. Attack sirens sounded, then cleared, and sounded again throughout the day. Point defense guns went off twice. Long-range rocket artillery dotted the island, telling Jennings that the Marines would be staying here for as long as they wanted. By that afternoon, twelve of those rockets had been fired. Meanwhile, cargo aircraft had begun to arrive on the newly cleared airfield, bringing supplies and removing prisoners from the island. Later, the Air Force would arrive with Warthogs and Eagles, perfect forward deploying patrol forces.

The Brickheads wouldn’t be repeating their performance any time soon. The rockets they’d been launched on, and the capsules they’d dropped into combat in weren’t reusable. The rocket boosters had burned themselves up, and the capsules had shed layer after layer on the descent, ablating chaff and micro-jammers all the way down. What was left of the capsules got shot to pieces as the island’s defenders responded to the Brickhead’s unwelcome arrival. More painfully, half the Brickheads had died that day.

Jennings didn’t know if they had any more rockets to ride, but he knew replacing the She-devils, Butterflies, and others who’d been lost wouldn’t be fast or easy. Then Jennings broke into laughter.

“What’s so damn funny?” asked Ajax.

“I finally get… why the Major… calls our armor… a three piece suit!” The other Brickheads were looking at Jennings like a strange animal, not sure if they should be worried or scared.

“Okay Jennings, I’ll bite. Why does the Major call our armor a three piece suit?”

Gasping for air and recovering somewhat, Jennings replied, “Because there are three pieces!” Quizzical looks met him. “We rode in on rocket ships, that’s one.” Nods of vague understanding met him this time. “And our armor and weapons, that’s two.” More nods.

“Alright, so what’s the third piece? And don’t say something cheesy like ‘friendship’ or ‘teamwork,’” Young asked. She could be real sentimental at times.

“Close! We’re the third piece. If we’re ever going to do this again, the Corps need more rockets, more gear, and more of us.” This last part sobered Jennings up. It was the thought of what and who would need replacement that sparked his understanding. It was the reminder that people would need replacing that broke the joke. People he knew. Whether those people would be replaced, whether new recruits would fill their boots, or whether any more of the ballistic missiles they’d launched on that morning would be acquired, it all depended on whether or not anyone thought what they did that morning was worthwhile. And whether it was still a bad idea.

Ryan A. Belscamper is a retired U.S. Navy Firecontrolman with Bachelor’s degrees in Mechanical and Electrical Engineering from Southern Illinois University. He is currently working as an Engineer with NSWC Crane.

Featured Image: “Soldier” by Richard Bagnall (via Artstation)