By David Polatty

Last week, the U.S. Naval War College hosted the annual EMC Chair Symposium, with this year’s offering bringing in experts from around the world to discuss maritime strategy. Vice Admiral Charles Michel, Vice Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, kicked off the event by engaging in an energizing discussion on the missions and functions of the U.S. sea services, with a special focus on current and future U.S. Coast Guard capabilities and activities. Understandably, he spent much of his time examining the traditional security, presence, and safety aspects of maritime operations. He also provided insight into the unique ways that the Coast Guard complements forward deployed U.S. Naval forces. As a key component of this forward deployment and naval presence dialogue, he reminded participants that humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) remains a core mission for militaries.

Participants spent the better part of the two-day event discussing challenges and opportunities facing the U.S. sea services. We had spirited dialogue on a broad range of warfighting issues viewed through the lens of maritime strategy. Prior to the last panel of the symposium, a HA/DR “urban humanitarian response” discussion, I was struck by the manner in which many attendees translated an overarching fear of Chinese and Russian aggression to pivot away from the non-warfighting roles that militaries fill. As my colleague and symposium chair, Dr. Derek Reveron has both written and said time and again, “navies do much more than fight wars.”[i]

We are at a critical point in history from a humanitarian perspective, with over 60 million people displaced across the globe – more than at any time since World War II. The United Nations (UN) and the humanitarian community are currently responding to four “L3 Emergencies” in Iraq, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. This designation reflects the global humanitarian system’s classification for a response to the most serious, large-scale humanitarian crises.[ii] A quick scan of the news reveals many other areas of the world where vulnerable populations face monumental challenges. While climate change impact predictions diverge greatly depending on the source, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates that between 250 million and one billion people across the globe will become displaced from their region or country in the next 50 years.[iii] As significant, heartbreaking, and perilous as the current migration crisis in the Mediterranean Sea is, it pales in comparison to what the world may face in the near future if even the low end of climate change projections prove to be true.

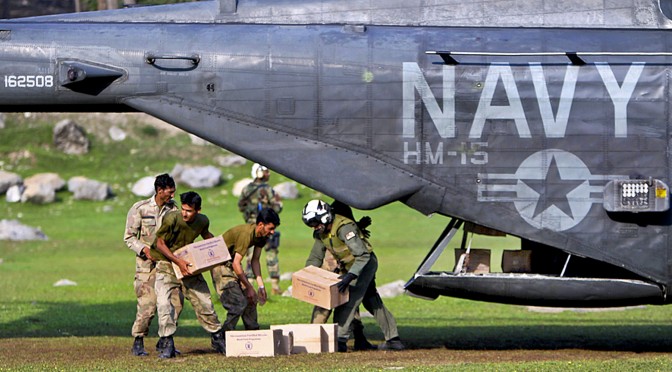

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps team spends much of its operational life training and exercising for war. We buy and maintain warships, combat aircraft, attack submarines, and amphibious capabilities that enable us to fight and win decisively. Many of these capabilities also provide critical life-saving support during natural disasters and complex emergencies. Because of the forward deployed nature of our naval forces, versatile multi-mission platforms, and ability to operate from the sea with minimal sustained footprint ashore, we are optimally positioned to conduct HA/DR operations. One area that the sea services need to spend additional time focusing on is the understanding of how military HA/DR missions can better integrate into civilian humanitarian responses. We must increase our education, training, and simulation opportunities in HA/DR to become more proficient when asked to respond.

The 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review ranked HA/DR #12 of 12 military missions, with respect to how the Secretary of Defense and Joint Staff plan to distribute forces to U.S. Combatant Commanders.[iv] Despite being the lowest priority, history has proven that our military will respond to save lives and alleviate human suffering when called upon to do so. A 2003 study by the Center for Naval Analyses found that from 1970 to 2000, U.S. military forces were diverted from normal operations 366 times for HA/DR operations, while only 22 times for combat.[v] While these numbers do not reflect the duration of each operation, they still provide a telling story about the frequency in which our military has responded to natural disasters and humanitarian crises.

To highlight what many argue is a systemic lack of understanding within the U.S. military on the current state of the international humanitarian system and how it functions, below is a “pop quiz” for CIMSEC readers. These are ten of the most important questions (and yes, there are many more…) that military personnel must understand in order to quickly and successfully integrate military capabilities into civilian humanitarian responses. (Note: answers are at bottom of the article for inquiring minds who want to know.)

- What are the four fundamental humanitarian principles and why are they so important?

- What is a humanitarian actor?

- What is the lead federal agency in the U.S. government for disaster response overseas and what relationship do they have with the U.S. military?

- What international organization brings together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies? Within this organization, who is responsible for facilitating civilian-military coordination, and what are the range of potential strategies for effective coordination?

- What is the “Cluster System”?

- What are the “Sphere Standards”?

- What are the “Oslo Guidelines”?

- What is a “MITAM”?

- What key information systems do humanitarian actors utilize to communicate?

- What are the key military capabilities that are routinely needed to augment the humanitarian community’s response to large-scale disasters?

After you write your answers down, please scroll to the bottom to see how you fared. There is no grading scale, because I suspect most of you, like the majority of the students who come through Newport, will quickly agree that we all have a lot to learn to be able to work effectively in the humanitarian space. It is in this intricate environment where civilian organizations operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, to help vulnerable populations around the world – through both sustained developmental efforts as well as disaster relief activities.

If you struggled with this academic exercise, or have taken part in the chaos that is a HA/DR operation and appreciate how different this mission set is from traditional naval operations, then you may agree in principle at least, with the following recommendations for improving our abilities in this area.

The U.S. Sea Services should make small changes within their education and training efforts to ensure that our personnel have a baseline understanding of foundational issues in civilian-military humanitarian response. While the UN, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and U.S. Pacific Command’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management all provide excellent training in this area, collectively they reach a relatively small audience. Generally speaking, our war colleges have minimal elements within their curricula that allow students to comprehend the most crucial civilian-military humanitarian issues. Very few HA/DR exercises and simulations are run on a regular basis, with one exception being the earthquake scenario within U.S. Pacific Command’s ‘Rim of the Pacific’ (RIMPAC) biannual exercise. RIMPAC brings together international militaries, humanitarian actors, and academics in a dynamic environment to simulate a complex response and learn from one another. Combining smaller “mini-exercises” for HA/DR within larger warfighting exercises, when appropriate, makes sense from both a fiscal and preparedness perspective.

The Naval War College recognizes the importance of HA/DR education, and thanks to a formal partnership with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, is collaborating closely with the UN’s Civil-Military Coordination Section, as well as several other universities, including Stanford, Yale, and Oxford. Our Civilian-Military Humanitarian Response Program aims to advance civilian-military engagement and coordination during complex emergencies and natural disasters, and improve the U.S. Navy’s effectiveness in conducting HA/DR operations. These collaborations have already informed curriculum, especially in our specialized planning courses that target operational (navy component and numbered fleet) and tactical (expeditionary strike group) staffs who will likely plan and execute HA/DR operations. We are working to develop new courses and simulations that will bring military and humanitarian personnel together in the classroom and during exercises. These partnership activities will help the humanitarian community create innovative frameworks for improving disaster coordination.

The U.S. Sea Services must, and will, spend the majority of their operational lives thinking about warfighting and maritime security. Current education and training systems ensure we retain our competitive advantage over future threats. However, minor investments in HA/DR education and training will help improve the predictability, effectiveness, efficiency, and coherence in deploying and employing military assets in support of humanitarian responses. This will allow us to build greater trust and confidence between humanitarian actors and military personnel, and ultimately improve our ability to respond during future natural disasters and complex emergencies.

Pop Quiz Answer Key

- What are the four fundamental humanitarian principles and why are they so important?

- Humanity, Neutrality, Impartiality, and Operational Independence.

- “These principles provide the foundations for humanitarian action. They are central to establishing and maintaining access to affected people, whether in a natural disaster or a complex emergency, such as armed conflict. Promoting and ensuring compliance with the principles are essential elements of effective humanitarian coordination.”[vi] Militaries must have an appreciation for the principles so they can better understand the humanitarian system they are integrating into and minimize potential disruptions and negative effects in the humanitarian space.

- What is a humanitarian actor?

- Humanitarian actors are civilians, whether national or international, UN or non-UN, governmental or non-governmental, which have a commitment to humanitarian principles and are engaged in humanitarian activities. Military actors are NOT considered humanitarian actors. “Even if they fulfill or support humanitarian tasks, the military is a tool of the foreign policy of a Government, and as such is not perceived as neutral or impartial. The separation of humanitarian and political or military objectives is not given or at least unclear – and military units are certainly not primarily perceived as humanitarians by the civilian population.”[vii]

- What is the lead federal agency in the U.S. government for disaster response overseas and what relationship do they have with the U.S. military?

- U.S. Agency for International Development, Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID OFDA) is responsible for leading and coordinating the U.S. government’s response to disasters overseas. The U.S. military acts in a supporting role to USAID OFDA during HA/DR operations.

- What international organization brings together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies? Within this organization, who is responsible for facilitating civilian-military coordination, and what are the range of potential strategies for effective coordination?

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA). UN OCHA’s Civil-Military Coordination (CM-Coord) Section has been designated the focal point in the UN system for humanitarian civil-military coordination. It supports relevant field and headquarters-level activities through the development of institutional strategies to enhance the capacity and preparedness of national and international partners. CM-Coord is “The essential dialogue and interaction between civilian and military actors in humanitarian emergencies that is necessary to protect and promote humanitarian principles, avoid competition, minimize inconsistency, and when appropriate, pursue common goals. Basic strategies range from coexistence to cooperation. Coordination is a shared responsibility facilitated by liaison and common training.”[viii]

- What is the “Cluster System”?

- This is UN OCHA’s system for managing a response. “Clusters are groups of humanitarian organizations (UN and non-UN) working in the main sectors of humanitarian action, e.g. shelter and health. They are created when clear humanitarian needs exist within a sector, when there are numerous actors within sectors and when national authorities need coordination support. Clusters provide a clear point of contact and are accountable for adequate and appropriate humanitarian assistance. Clusters create partnerships between international humanitarian actors, national and local authorities, and civil society.”[ix]

- What are the “Sphere Standards”?

- “The Sphere Handbook puts the right of disaster-affected populations to life with dignity, and to protection and assistance at the centre of humanitarian action. It promotes the active participation of affected populations as well as of local and national authorities, and is used to negotiate humanitarian space and resources with authorities in disaster-preparedness work. The minimum standards cover four primary life-saving areas of humanitarian aid: water supply, sanitation and hygiene promotion; food security and nutrition; shelter, settlement and non-food items; and health action.”[x]

- What are the “Oslo Guidelines”?

- These are UN OCHA guidelines for improving the effectiveness of foreign military and civil defense assets in international disaster relief operations.[xi] While not binding, they often frame how international militaries will interact with humanitarian organizations during actual responses.

- What is a “MITAM”?

- USAID OFDA often employs a “Mission Tasking Matrix” to request specific support requirements from the U.S. military. This is currently in the form of an excel spreadsheet and prioritizes requests for military support.[xii]

- What key information systems do humanitarian actors utilize to communicate?

- gdacs.org, www.reliefweb.int, www.humanitarianresponse.info, https://data.hdx.rwlabs.org/ and many others.

- What are the key military capabilities that are routinely needed to augment the humanitarian community’s response to large-scale disasters?

- Airlift (both rotary wing and fixed wing)

- Air traffic control

- Communications

- Engineering and construction

- Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance

- Logistics and supply

- Medical

- Operational planning expertise

- Relief supplies including water production and utilities

- Sealift (depending on the geography of the affected nation)

- Search and rescue

- Security (with caveats)

David Polatty is a civilian professor at the U.S. Naval War College, where he teaches strategic and operational planning and leads the College of Operational & Strategic Leadership’s new “Civilian-Military Humanitarian Response Program.” He is also a Captain in the Navy Reserve and currently commands NR U.S. European Command J3. The views and opinions in this article are his own and do not represent the views or position of the U.S. Naval War College, U.S. Navy, or Department of Defense.

[i] http://www.navy.mil/submit/display.asp?story_id=93802

[ii] http://www.unocha.org/where-we-work/emergencies

[iii] http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/10/14/cambio-climatico-mas-desplazados-que-un-conflicto-armado

[iv] http://archive.defense.gov/pubs/2014_Quadrennial_Defense_Review.pdf

[v] http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~gorenbur/all%20responses.pdf

[vi] https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OOM-humanitarianprinciples_eng_June12.pdf

[vii] https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/UN%20OCHA%20Guide%20for%20the%20Military%20v%201.0.pdf

[viii] https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/v.2.%20website%20overview%20tab%20link%201%20United%20Nations%20Humanitarian%20Civil-Military%20coordination%20(UN-CMCoord).pdf

[ix] http://www.unocha.org/what-we-do/coordination-tools/cluster-coordination

[x] http://www.sphereproject.org/handbook/

[xi] https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/Oslo%20Guidelines%20ENGLISH%20(November%202007).pdf

[xii] https://www.usnwc.edu/mocwarfighter/Link.aspx?=/Images/Articles/Issue1/MITAM_Example_(MOC_Warfighter).xls