By LCDR Jason Lancaster

Introduction

Peter Wessel was only 10 when the Great Northern War started, and he was 30 when it ended in 1720. In nine brief years he rose from naval cadet to Vice Admiral. I first learned of Peter Wessel, also known popularly known as Tordenskjold (Thunder Shield), in a Danish film, Satisfaction 1720. The film depicted Tordenskjold as a depraved and lecherous idiot exploiting wartime victories which were stumbled upon through accident, and pursues a novel theory into his untimely death in a duel. This film led me to further explore both the Great Northern War and the life of this remarkable naval officer. Unsurprisingly, the movie’s account of his personality vastly differs compared to the few English language books about him. Although Denmark and Norway share streets and warships named after Tordenskjold, his name and deeds are largely unknown in the English speaking world. His exploits along the Baltic coast deserve remembering.

Sweden Ascendant

Sweden’s main political goal of the 17th century was the establishment of Dominium maris baltici, or Swedish domination of the Baltic Sea. Sweden’s defense of Protestantism and its major military contributions to the outcome of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) had enabled Sweden to acquire a sizable portion of the Baltic coast and operate as the dominant power in the Baltic Sea. However, the British and Dutch prevented Sweden from exercising complete domination of the Baltic coast.

Sweden’s preeminence was resented by the other Baltic powers. In 1697 King Charles XI of Sweden died, leaving his fifteen year old son, Charles XII, on the throne. The other Baltic states saw their opportunities for territorial expansion. That year, Peter the Great, Emperor of Russia and Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, met in Dresden. The two men shared much in common; they were both tall, incredibly strong, and fond of drinking. They agreed to an alliance against Sweden. But despite their mutual desire for war, both needed time to prepare. Augustus had just been elected King of Poland with Peter’s help and needed more time to solidify his rule. Peter needed to conclude a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire before he could turn his attention to the Baltic. Both Peter and Augustus sought additional allies for war and found King Frederick IV of Denmark. The three nations formed an alliance to attack Sweden from all sides, overwhelm the boy-king, and divide the Swedish empire.

Unfortunately for the allied powers, despite Charles XII’s youth, he was no pushover. Charles XII demonstrated his military prowess by defeating each power in turn. Denmark was forced out of the war by August 1700, after the Swedes almost captured Copenhagen. The Saxon/Polish forces invaded Livonia, but were defeated, and Saxony/Poland was driven out of the war by 1706, with Augustus the Strong forced to cede the throne of Poland to a Swedish puppet. From 1702-1710, the Russians and Swedes fought over the coasts of Ingria and Karelia. Initially, the Swedes had the upper hand, winning victories at Narva (1700), but the Russians eventually pushed the Swedes back, and Peter established the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703 with the construction of the Peter and Paul Fortress. After Sweden’s crushing defeat at Poltava (1709), Augustus the Strong and Frederik IV rejoined Peter the Great along with George I, Elector of Hannover. In 1714, George was crowned King of Great Britain, bringing Britain into the conflict. In 1712, Frederich William Elector of Brandenburg and King in Prussia also joined the conflict, setting the stage for a rapidly escalating war.

Peter Wessel joins the Navy

Peter Wessel was born the 14th child of a Trondheim merchant. His family owned multiple ships and several of his elder brothers served at sea in the Danish Navy or merchant marine. Peter wanted to follow in their footsteps, while his mother wanted him ashore either as a cleric or a member of whichever guild would accept him. School bored Peter, and he spent a great deal of time fighting bullies instead of studying his ablative absolutes. During the winter of 1704, at the age of 14, Peter ran away from apprenticeships as a tailor and barber-surgeon and set off on foot for Copenhagen to find himself an appointment to the Danish Naval Academy.

In 1704, King Frederick IV visited Trondheim, offering an opportunity. Peter Wessel hid himself amongst the royal retinue for the trip to Copenhagen. During the arduous trek across Norway, Peter observed how the king had cheerily received audiences of common people and spent time with them in stables and around campfires. Peter decided that he could reach out to the approachable king for help.

When Peter arrived in Copenhagen he called on his father’s old classmate, Dr. Jespersen, the King’s Chaplain. Peter told him his story, and asked for help getting into the Naval Academy. The king often visited Dr. Jespersen, and on one summer’s day in 1705, Peter asked the king for a naval academy appointment during his usual visit to Dr. Jespersen’s stable. Unfortunately, that year’s class had been shrunk by half to 52 cadets and there were no vacancies. King Frederick promised Peter that he would get a spot. While waiting for an appointment, Dr. Jespersen tutored Peter and taught him to channel his bountiful energy. Another year passed and still no appointment. Dr. Jespersen returned home from the palace one day with the king’s response, “no vacancies.”

Peter’s brother Henrik was a Danish Navy Lieutenant, although he had never actually served aboard a Danish warship, rather he had served on a Dutch man-of-war and was heading east to serve aboard a Russian warship. Henrik said Peter would benefit from time at sea aboard a merchant ship gaining experience until his appointment. Henrik had a Dutch shipmate who was Chief Mate aboard a Danish West Indiaman, Christianus Quintus, shortly bound for the West African coast for a cargo of slaves to sell in the Americas. Henrik got Peter a berth as the most junior of five cabin boys. Peter received valuable experience during the voyage in seamanship, gunnery, and navigation which prepared him for the Naval Academy and future voyages.

After two years at sea, Peter returned to Copenhagen. With still no naval academy appointment awaiting him, 18-year old Peter again wrote King Frederick detailing his experiences at sea and the king’s promise of an appointment. The letter failed to produce results, however, Peter was allowed to take the entrance exam and then join the Naval Academy as a volunteer with no pay or uniform until a billet opened in the class. Peter knew his father would pay his expenses and that he could continue to live with Dr. Jespersen.

Just as things were looking up, Peter received a letter from Trondheim. His family’s property had been destroyed during a fire. With no way to maintain himself at the naval academy, Peter signed on as a deck hand on a Danish East Indiaman bound for India. On October 5, 1708 Peter sailed for India, and during the journey his appointment as a cadet at the naval academy was signed by the king on January 11, 1709. During the voyage Peter was promoted to Boatswain’s Mate and then to 3rd Mate. In May 1710, Peter’s ship arrived off the Norwegian coast to learn that Denmark had re-entered the war against Sweden. The ship’s master was unwilling to risk the passage to Copenhagen through swarms of Swedish privateers and pulled into Bergen to await a convoy. Peter displayed the impatience which would bring him future battle glories and signed on as a sailor aboard a neutral British merchant ship bound for Germany via Copenhagen.

Again, misfortune followed Peter. The ship became wind-bound in the Kattegat and pulled into Marstrand, Sweden. Peter was a Danish officer, not in uniform and dressed in English clothing meaning Peter could have been hung as a spy. Peter decided to have a look at the town while the ship was in port. He posed as a Dutch sailor and spoke to sailors, soldiers, and townsmen in the taverns and waterfront and observed the placement of batteries throughout the area. Once the British ship put to sea, Peter found a Danish warship to carry him to the Danish squadron under the command of Admiral Barfoed carrying the Governor-General of Norway Baron Løvendal. Peter reported aboard and then made his report to the two leaders. Baron Løvendal was impressed with both Peter’s demeanor and his clear reports on Swedish dispositions at Marstrand. The Baron had Peter assigned to his personal staff until Peter was able to be delivered to the naval academy.

Junior Officer

Peter started at the naval academy in September 1710. After three years before the mast, Peter found the curriculum boring. Again, he wrote to the king detailing his experiences and asking for a commission. In April 1711, Admiral Sehestad, the naval academy superintendent handed Peter his commission as a temporary sub-lieutenant and his orders to report to Postilion. Postilion’s executive officer billet was gapped, and Peter’s experiences at sea made him the most qualified officer aboard to fill the gapped XO billet. In less than a year, Peter had gone from naval cadet to XO of a frigate.

Postilion was a 26-gun frigate purchased from the French and assigned to convoy duty. The French had equipped Postilion with 26 twelve pounders, but the Danish Navy had downgraded them to six and eight pounders. The administrators of the Danish Navy preferred smaller cannon because they consumed less gunpowder which saved money. The tactical disadvantage was not a concern to them. The Postilion‘s convoy duties were slow, boring, and frustrating. Protecting merchant ships that might or might not want to stay in formation from one port to the next was not the exciting duty that an active junior officer sought.

After escorting a convoy to the town of Langesund, near Christiana, Peter went ashore with dispatches. He heard of a Norwegian, Jørgen Pedersen, constructing small ships called snows in Langesund for General Løvendal. Warships had not been constructed in Norway since the Vikings, but Peter was one of only two naval officers to visit the shipyard. The two Norwegians got along well, both because of Peter’s interest in the snows under construction and because Jørgen Pedersen had helped construct Postilion in France. The two discussed Peter’s current ship.

Peter knew that he would not make his name as XO of a frigate on convoy duty, but he had a plan. The new snows that Jørgen Pedersen was constructing needed captains. Who better than himself to take a small ship to harass the Swedes along the rock strewn coasts of Sweden? The governor general of Norway was still Baron Løvendal, whom Peter had served with before starting at the naval academy, and Peter brought him dispatches from Denmark. The two former shipmates discussed Peter’s rapid promotion, the Baron’s plans for the new snows being constructed, and the war in Norway. Peter left the Baron with an order to take command of one of Pedersen’s new snows, Ormen, which boasted a crew of 46 and mounted five cannons including two 4 pounders, two 2 pounders, and a single one pounder. After less than 12 months in the navy, Peter was captain of his own ship.

Løvendal’s Galei

Jørgen Pedersen not only constructed four snows for the Norwegian defense forces, but he also constructed an 18 gun frigate. In typical Danish fashion, she was under armed, boasting 12 six pounders and 6 four pounder guns. When the frigate was completed, Baron Løvendal appointed Peter the captain. In honor of his friend and patron, Peter named the ship Løvendal’s Galei. Peter desired to continue his depredations along the Swedish coast, but his frigate was often busy supporting the fleet in the Baltic campaign against Stralsund and convoy duty in the North Sea.

Previously as captain of the Ormen, Peter operated along the Swedish coast, capturing Swedish privateers and scouting for Baron Løvendal. Later, on 26 July 1714, Peter earned his most famous exploit from his time as captain of Løvendal’s Galei; a single ship duel with the 28-gun Swedish privateer Olbing Galei. The Swedish privateer was English built and captained by an Englishman. The two ships both approached under false colors. Olbing Galei under the English flag, and Løvendal’s Galei under Dutch colors. Once the vessels had neared they replaced the false flags with the flags of Sweden and Denmark. Despite the disparity in broadside, Løvendal’s Galei hit Olbing Galei hard causing major damage to the rigging, and then the two ships fought for 14 hours until Peter ran out of powder and shot.

With ammunition gone, Peter sent a messenger to Olbing Galei stating that the only reason he was not discontinuing the action out of cowardice, but only because he was out of ammunition. Peter asked for powder and shot to continue the fight. Captain Bachtman declined to give him the ammunition, ending the fight. The two captains then toasted each other as they sailed away.

Peter wrote his dispatches to two people, General Hausman, now in charge of Danish forces in Norway, and King Frederik in Denmark. From Norway, General Hausman sent Peter his hearty congratulations. From Denmark came court martial proceedings. Peter’s rapid promotions had created many enemies in the Danish Navy. The dispatch for the king was taken by one of Peter’s enemies and subsequently distorted to damage his career. Peter was charged with recklessly endangering his command by fighting a ship superior to his own and for disclosing valuable military secrets by telling the enemy ship that he lacked ammunition, and other unspecified charges. The Judge Advocate General proposed demoting Peter to sub-lieutenant and forfeiture of six months’ pay.

On December 15, 1714 the court martial concluded. 10 of 14 members of the court voted for acquittal. The court martial was composed of eight admirals and six commodores and captains. The four most junior members voted for Peter’s demotion. This vote reflected the bifurcated reputation of Peter Wessel. His rapid rise threatened many of his peers from sub-lieutenant to captain, however, admirals approved of his victories. Upon conclusion of the court martial Peter visited King Frederik. He brought two documents with him; acquittal papers from the court martial and an application for promotion to captain, which the king accepted. On December 28, 1714 Peter Wessel was promoted to captain.

Dynekilen

King Charles arrived in Stralsund, Swedish Pomerania in 1714 after having spent the past five years in Turkey. The city had been under siege since 1711. King Charles wanted to use Swedish Pomerania as a launching point for a renewed offensive against the Saxons and Russians. Unfortunately, Peter and the Danish fleet prevented Sweden from reinforcing Stralsund. Multiple times Peter’s ship fought larger more heavily gunned ships and prevented their relief of Stralsund. In December, 1715 the city fell to the Dano-Saxon-Prussian forces besieging the city. Charles XII might have been losing the war, but he was not going to make peace. Instead, he escaped from Stralsund and returned to Sweden to continue the war.

In October, 1715, in honor of Wessel’s work preventing the Swedish Navy’s reinforcement of Stralsund, he was knighted. His new name and title, Tordenskjold, meant thunder shield, in reference to his thundering attacks against the Swedes and his defense of Denmark.

In March, 1716, King Charles decided to invade Norway. He split his forces to simultaneously to attack Christiana and Frederikstad. The roads in this part of Norway were poor and often impassable, therefore Swedish supplies had to come by sea. Swedish forces took advantage of the rocky islands strewn across coastline between Marstrand and Frederikstad to run supplies from fortified point to fortified point to reach the army’s supply depots outside Frederikstad. The Swedes used shallow draft galleys that hid in inlets and coves where the deep draft Danish squadron could not go. If Denmark could sever the Swedish sea lines of communication (SLOCs) they could isolate the Swedish army and end the campaign. Danish Admiral Gabel wrote to Tordenskjold explaining the situation. Characteristically, he immediately sought action.

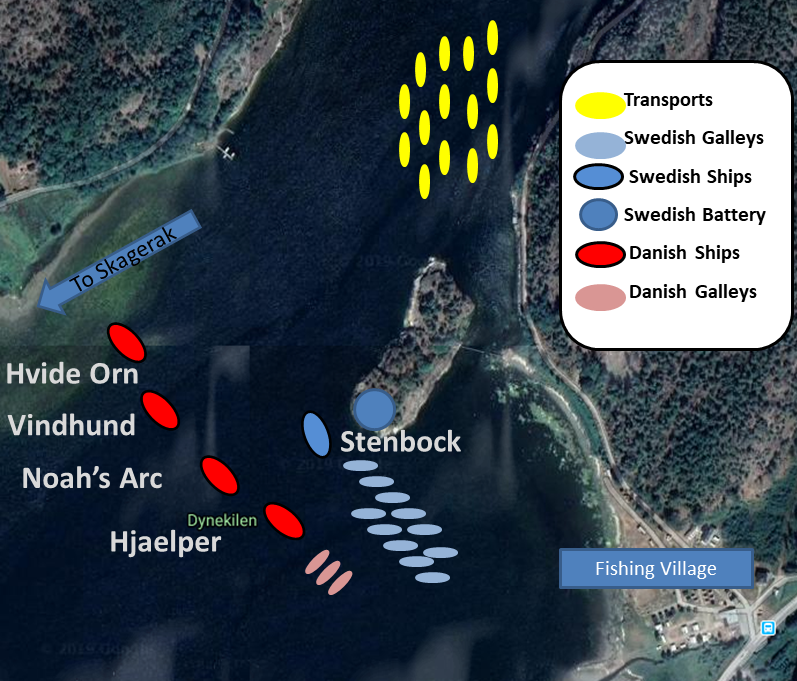

On 7 July 1716, Tordenskjold discovered a Swedish force at anchor behind a battery in deep in the Dynekilen Fjord, which featured between 14 and 29 Swedish transports as well as 15 escorts ranging from 24 to 5 guns each as well as a battery of 6 twelve pounders. Tordenskjold advanced into the fjord with four frigates and three galleys. Tordenskjold subsequently landed soldiers on the island to take the battery. The fire from his frigates overpowered the escorts; Stenbock surrendered, and the galleys crews attempted to ground and fire their vessels. Tordenskjold proceeded to take or burn as many transports as possible. Swedish soldiers began to arrive and threaten his position, but Tordenskjold calmly took his prizes and destroyed any ships he could not cut out and then sailed out of the fjord.

The battle was a decisive victory for Denmark. According to Danish records, Tordenskjold had captured seven warships and 19 transports, but Swedish records however list Tordensjkjold as having captured seven warships and 14 transports. The actual numbers are less important than the result of the battle. Swedish forces besieging Frederikstad halted the siege and withdrew. Sweden’s offensive capabilities were crippled until 1718. As a result of his success, King Frederik promoted Tordenskold to Commodore (Rear Admiral).

Conclusion

Between 1716 and 1720 Tordenskjold continued to fight the Swedes. He attacked Swedish forces in Stromstad, Marstrand, and Goteborg. In nine brief years he rose from a naval cadet to the rank of Vice-Admiral in the Danish Navy. His seamanship, calmness amidst chaos, and intrepid leadership created opportunities for victory. His men loved him for his demeanor, but his rapid rise created enemies in the Danish officer corps. He was not the buffoonish character as seen in the film Satisfaction 1720; that man would never have succeeded at sea.

In 1720, Denmark’s role in the Great Northern War ended. His heroism and seamanship played a major role in ensuring Denmark was on the victorious side of the conflict. Later, Peter contemplated marriage with an English aristocrat and service in the Royal Navy. But at the age of 30, Peter Wessel Tordenskjold was killed in a duel with Colonel Jacob Stael von Holstein over a game of cards. Tordenskjold’s second was Lieutenant Colonel Georg von Münchhausen, father of the famous Baron von Münchhausen. Today, Norway and Denmark both claim Tordenskjold as a hero. Both Denmark and Norway named warships after him, and today he is buried in Denmark.

Sweden began the war as a major European power, and ended the war reduced to the status of a second rate power. With the exception of Swedish Pomerania, Sweden lost the entire southern rim of the Baltic. Russia demonstrated her arrival as a leading European power, gaining dominance over the eastern Baltic and a window to the west: the port cities of Saint Petersburg, Reval, and Riga.

Although Denmark was on the winning side of the war, she did not achieve her objectives. Although Denmark occupied Swedish Pomerania for five years after Stralsund fell, the province was returned to Sweden at the making of peace. The territories of Bohuslen and Scania remained Swedish. The maritime powers of Great Britain and the Netherlands would not allow one nation to control Øresund, the Kattegat, and Skagerak. The Baltic trade included valuable commodities for sea power, including cordage, tar, and trees. In order to maintain their maritime dominance, the maritime powers of Britain, France, and the Netherlands would not let a single nation control the entrance to the Baltic Sea and monopolize the trade. Denmark won the war, but lost the peace.

LCDR Jason Lancaster is an alumnus of Mary Washington College and has an MA from the University of Tulsa. He is currently serving as the N8 Tactical Development Officer at Commander, Destroyer Squadron 26. His views are his own and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

Bibliography

Adamson, Hans Christian. Admiral Thunderbolt. Philadelphia and New York: Chilton Company, 1959.

Anderson, M.S. Peter the Great. New York: Longman Group, 1995.

Anderson, Roger Charles. Naval Wars in the Baltic during the Sailing Ship Epoch, 1522-1850. London: C. Gilbert Wood, 1910.

Bjerg, Hans Christian. “På kanoner og pokaler.” Dankse Tordenskjold Venner. July 24, 1964. https://archive.is/20130212170512/http://www.danske-tordenskiold-venner.dk/tordenskiold/artikler/02_kanon_pokal.htm (accessed October 12, 2019).

Denner, Balthasar. “Portrait of Peter Jansen Wessel.” Danish Museum of National History. Portrait of Peter Jansen Wessel. Frederiksborg, Denmark, 1719.

Jonge, Alex de. Fire and Water: The LIfe of Peter the Great. New York: Coward, McCann, and Geoghegan, 1980.

Molstead, Christian. On Guns and Cups, 1925.

Featured Image: “Paa kanoner og pokaler” (On guns and cups), depicting the episode 27th july 1714 where the danish frigate Lövendals Galley commanded by norwegian officer Tordenskjold encounters the swedish-owned, former english frigate De Olbing Galley on the swedish westcoast. After a long fight the danish ship runs out of gunpowder, and the ships part after a toast between the two opponents. (Book Strömstad : gränsstad i ofred och krig by Nils Modig, page 134, via Wikimedia Commons)