Our “Sacking of Rome series continues” with a sixth installment!

By Steven Wills

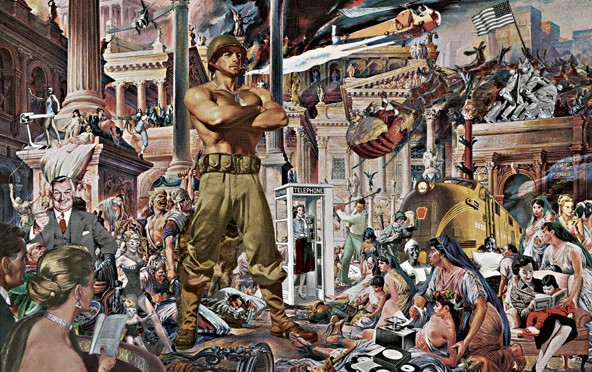

Most popular portrayals of the Roman Army focus on the collapse of the Republic, as in the HBO “Rome” series, or the classical “high” empire as illustrated by the Russell Crowe epic “Gladiator”. In contrast to these theatrical efforts is the period of the so-called “late” Roman Empire of 220 A.D. to the 600’s. It offers significant lessons in how not to manage the army of a great power. While there are many possible causes for the downfall of the Roman Empire and resultant Dark Ages, military historians generally agree that three specific actions of Roman elites in the late Empire specifically contributed to the Empire’s eventual collapse. Cutting the retirement benefits of a small professional force in favor of smaller taxes for the elite and greater benefits for the masses served only to weaken the desire of Roman citizens to serve. When the Roman citizenry would not join in the numbers required to protect the Empire, Roman elites turned to conscription, which produced only disgruntled recruits, and mass recruitment of barbarian tribes such as the Goths, Visigoths and Vandals. These tribesmen could be paid less and did not require expansive pensions as an incentive to serve. The so-called “barbarization” of the Roman Army seriously weakened its core values, made it more likely to rebel against Roman authority, and ultimately brought disaster to the gates of Rome itself in 410 A.D. These three mistakes in the management of the late Roman Imperial Army should serve as a powerful warning to American elites seeking inexpensive solutions to the maintenance of American military power. While some military spending can always be reduced, a great power that seeks very low-cost solutions does so at its own peril.

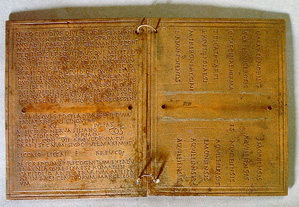

The Roman Army began providing pensions to retiring soldiers during the fall of the Roman Republic in the late first century B.C. Competing Roman leaders such as Julius Caesar, his great rival Pompey Magnus, Caesar’s nephew Octavian, later known as Augustus Caesar, and his famous opponent Marc Antony all offered grand incentives to retain the loyalty of their soldiers. These promises often included financial rewards, exemption from taxes and grants of land from captured enemy territory. Augustus Caesar continued this practice when he consolidated power in the first century A.D. and became virtual dictator of the Empire under the title of Princeps (first citizen). Augustus reduced the Roman Army to a voluntary, professional force of approximately 150,000 active duty soldiers and a similar number of auxiliary troops. A soldier who served 20-25 years of active military service (accounts vary) would be eligible for the honesto missio, or honorable discharge from military service. Similar benefits were provided for soldiers disabled in the line of duty and unable to return to service. The soldier was provided an exemption from Roman taxes, a plot of land and appropriate work animals, and often a job in the imperial administration of the territory in which they settled. Roman veterans could be recalled to active duty in case of emergency and often provided a reliable, loyal citizenry in newly conquered territories. As the Empire grew, successive leaders, now styled as Emperors widened the veteran benefits until the mid third century A.D. After this troubled period of revolts, barbarian attacks and economic downturn and collapse, Roman authorities gradually reduced pensions and lengthened the period of active service necessary to receive full credit for service. This appears to have been done to reduce taxes for wealthy Romans living in the provinces. Record are fragmentary from the later empire, but at some point in the third century A.D., bronze tablets replaced parchment documents as official evidence of service due to the inability of veterans to get the benefits they deserved. In addition, the empire’s policy of “bread and circuses” (generous food benefits and cheap entertainment) seemed a much better deal for the average lower class Roman citizen rather than increasingly dangerous and unrewarded services in the late Roman Army. As a result of these changes it would appear that the average lower class Roman citizen, the historical pool for legionary recruitment was much less inclined to a military career.

As Roman citizen recruitment failed to provide enough troops to protect an increasingly threatened Empire, Roman elites turned to conscription and barbarian recruitment. Conscripts were often ineffective and actively avoided reporting for duty. Some maimed themselves to ensure they would be found unfit for service. Recruitment of barbarians however offered a low cost solution to the manpower drain on the Roman Army. German tribes fleeing from the vicious Huns were desperate for sanctuary within the Empire and Roman officials equally needed soldiers to resist invasions. They negotiated with tribal chiefs for the military service of whole tribes in return for farmland for the tribe within Roman borders. Unfortunately, unscrupulous Roman officials were happy to defraud the tribesmen of their promised land, or commit them into combat situations where the highest casualties resulted. Such actions bred intense distrust and contributed to a uneasy co-existence of Roman and tribesman within the empire’s borders.

The Romans further weakened their “barbarized” Army by neglecting the “Romanization” of the new recruits. Since the city on the Tiber River first mounted military operations, it actively absorbed new soldiers from the ranks of its enemies. These new recruits were not only trained in Roman ways of war, but were culturally and constitutionally converted into Roman citizens. They eagerly embraced Roman baths, aqueducts, regular salaries, and other aspects of Roman law and culture. While such a procedure was effective with small groups of new soldiers, whole tribes of new barbarian recruits actively resisted Romanization. Roman officials were either unable or frankly too lazy or disinterested to continue this long-running successful process. Instead, the Roman Army was “barbarized” and became more German than Roman. The rigorous individual and team training that had been the hallmark of Roman arms for centuries was allowed to degrade in order to more easily employ the cheaper barbarian forces. The tribal contingents’ loyalties often swung between imperial employers and barbarian roots and culture. The Roman elite’s disdain for this force caused further tension and when the tribes were denied pay and food, they actively rebelled. This rebellion brought the Visigoth leader Alaric to the gates of Rome in 410 A.D. seeking food and payment for prior military service. When Roman elites refused, common people in Rome, fearing a long siege and starvation, opened the gates of the city to Alaric and his men. Then in turn sacked the city and destroyed or stole countless works of art. They also seized most of the city’s gold and silver. The Western half of the Roman Empire never recovered from this disaster. It lingered on with greater barbarian influence until tribesmen deposed the last Western Roman Emperor Romulus Augustulus in 476 A.D. The Eastern Empire had suffered a similar devastating defeat at the hands of Goths in 378 A.D. Rather than continue to accept barbarian recruits, it purged its army of tribesmen and returned to traditional Roman methods of training. In contrast with the west, this Eastern Empire endured for nearly another 1000 years. In summation, the Roman attempt to employ cheap alternatives for defense was an unmitigated disaster.

What can the United States learn from the example of the late Roman Empire? First, the maintenance of a professional force requires a generous pension system in order to maintain a steady supply of proficient recruits. According to former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen in 2011, only 7-11% of all military personnel complete 20 or more years of service and become eligible for a pension. Given that only 1% of Americans even serve in uniform, is a well funded U.S. military pension system such a great price to ensure a steady supply of recruits to serve the military needs to the Republic? Reduced benefits may convince many Americans, as it did Romans, that long-term military service is not worth the low pay and arduous conditions involved to attain an increasingly modest pension.

Distributing smaller benefit amounts to a wider percentage of the active duty force, or worse yet, paying larger benefits only to those who served in combat will likely weaken the force cohesion and generate needless class struggle within the ranks. The Romans attempted similar measures by paying barbarians less than purely Roman forces and price was a loss of cohesiveness and team-building within the ranks. In addition, rather than weld the fighting forces together in the shared experience of American culture, the services emphasize their differences by an over-emphasis on cultural diversity. The Romans Army of the high empire was extremely diverse and fielded units recruited from the British Isles to the deserts of Syria. It accommodated dozens of faiths and creeds within the shared Roman experience without the need to over-emphasize their differences. This successful system endured for centuries and served to insulate the legions from purely nationalistic strife.

The experience of the late Roman Army has much to offer the United States in the present. A professional military force needs a healthy pension structure. Post service benefits are essential to the retention of a moderate-sized group of highly trained professionals necessary to wage modern war. It is unwise to ignore the traditional sources of voluntary recruitment in search of lower-cost military solutions. Finally, the shared experience of voluntary service to a strong national ideal united disparate nationalities within each Roman legion. Discarding this unifying, albeit expensive construct in favor of larger numbers of low cost conscripts and barbarians served only to hasten the empire’s end. The United States would do well to consider the fate of the late Roman Army as it seeks low cost, effective substitutes for current defense expenditures. In the end, a nation gets either what it pays or refuses to pay for in maintenance of national security.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD candidate in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941.