This week, we talk about our military’s Strategic Goals, Strategic Planning, and Strategic Communication; Tim Walton, Delex consultant and Annie George, CIMSEC President, join us for Episode 2- Strategy (download).

Tag Archives: QDR

The Quadrennial Defense Review 2014 and Europe

Matteo is a researcher at the European Institute for Asian Studies in Brussels. He holds an Italian Master’s Degree in Law and an LL.M. in International Legal Studies from the Georgetown University Law Center, specializing in International and National Security and the Law of the Sea. He has collaborated with the University of Rome and the Italian Foreign Ministry in a training course for the Yemeni Coast Guard for anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, teaching a course of Law of the Sea, International Law and Security. This article is a part of The Hunt for Strategic September, a week of analysis on the relevance of strategic guidance to today’s maritime strategy(ies).

As the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) gets underway on the Western side of the Atlantic, the Old Continent is still grasping with the many fundamental changes in the U.S. military strategy, and with a few issues of its own. The economic crisis is far from over in Europe, and while sequestration has taken its toll in the U.S., it is still unclear whether NATO and the EU will eventually enact similar cuts. Moreover, the last European Security Strategy is dated from 2008 (a review of the original 2003 strategy), and Europe finds itself with a desperate lack of leadership in security policy. Its leading country, Germany, seems to have adopted a semi-isolationist approach to foreign policy,1 the United Kingdom is facing an increasing wave of euro-skepticism and general disengagement from security crises, while most of the other countries of Western Europe are still coping with the economic crisis.

As the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) gets underway on the Western side of the Atlantic, the Old Continent is still grasping with the many fundamental changes in the U.S. military strategy, and with a few issues of its own. The economic crisis is far from over in Europe, and while sequestration has taken its toll in the U.S., it is still unclear whether NATO and the EU will eventually enact similar cuts. Moreover, the last European Security Strategy is dated from 2008 (a review of the original 2003 strategy), and Europe finds itself with a desperate lack of leadership in security policy. Its leading country, Germany, seems to have adopted a semi-isolationist approach to foreign policy,1 the United Kingdom is facing an increasing wave of euro-skepticism and general disengagement from security crises, while most of the other countries of Western Europe are still coping with the economic crisis.

As such, the European perspective on the 2014 QDR needs to focus on several aspects: the current and future trends of European Defense spending, the refocusing of U.S. strategies in Europe and globally, NATO and the EU’s role, and possible improved NATO-EU partnerships.

European Defense Spending

The latest study on European Defense spending has revealed that the “number of active-duty military personnel across Europe has declined at a faster rate than has defense spending”,2 although in the last four years “the differential between reductions in manpower and declines in defense spending has started to shrink”.3 Does this mean that Europe has reached its minimum force reduction?4 And if yes, how will it affect further defense cuts?

It is important to note a few issues before delving into a deeper analysis. Europe, as a continent, still has more troops than the U.S. – which is also mainly due to having several national armies, which obviously entail a duplication of positions that the U.S. does not have – and does not benefit from a shared military budget, again due to national constraints.

That being noted, it is still likely that European countries will proceed to further cuts in the military,5 possibly aiming for more specialized and technologically advanced forces, basically perpetuating the typical European approach “quality is better that quantity”. It is important to note that such cuts, as it is the case in the U.S., are also often borne more from a political need than a strategic one, thus it remains to be seen if quality will replace quantity for all European countries. Moreover, it will be important to monitor the retirement plans for the reduction of army personnel. In other words, once cuts are enacted, the hiring policies of the various countries will have to be closely analyzed, as European countries have stronger welfare policies which could severely constrain the quality push of leaner military forces.

A latest theme in terms of improvement of training and equipment is the current focus on Key Enabling Technologies,6 which aims at retaining the European edge in terms of technological advancement and R&D through improved coordination, at least within the European Union. Given the traditional reticence of some member states to collaborate in the areas of national and regional security, the effectiveness of such coordination is not assured.

In other words, the situation in Europe is uncertain, surely due to the economic crisis, but also due to the upcoming 2014 elections for the European Parliament, the end of the term for the European Commission and Council (the executive branches of the European Union), also in 2014, which will surely affect future defense strategies.

Refocusing of U.S. Strategies

From this side of the Atlantic, it is unclear which are the priorities for the U.S. in terms of defense and general strategic deployments. Many were disoriented at the time of the Pivot to the Pacific, as the policy was not completely explained, and seemed to bypass the usual strategic channels (especially in an area where NATO would not be deployed). To this day, it is still unclear what the U.S.’ strategic priorities are. Apart from standard declarations underlining the long-standing relationship with Europe and the importance of NATO it is hard to read the U.S. foreign policy and its inclusion of Europe. The recent deployments of forces in the Mediterranean are the perfect example. European countries almost forced the U.S. to intervene in Libya, and only after the initial strikes was NATO was involved completely. Conversely, the U.S. took a policy decision on Syria, trying to involve European allies in a not very coordinated manner, with the result of losing support from both the interventionist and non-interventionist sides.

While some claim that the 2014 QDR will reshape the concept of U.S. bases in the world, maybe pushing for further cuts abroad in favor of rapidly deployable forces,7 it is difficult for Europe to anticipate the effects of possible re-deployments. European countries understand very well that with the end of the Cold War the continent lost much of its value as a strategic territory, and the many U.S. bases across Europe may be closed or re-deployed at any time, but it is also clear that such decisions would only worsen the strategic relations across the Atlantic if taken unilaterally.

Regardless of the possible outcome of the 2014 QDR, it is apparent that improved coordination with Europe would be cost-effective and beneficial to the U.S. Moreover, NATO was specifically designed to protect transatlantic security, thus it constitutes the perfect forum for this sort of discussion or negotiation.

NATO and EU: Their Roles and Possible Partnerships

As much as European countries have understood the shifting of importance of the continent after the Cold War, NATO too has had to cope with evolving times. While the past 20 years saw the organization’s active involvement in many areas, it is apparent that today’s transatlantic relations call for a reshaping of the organization in a definitive fashion: underlining its importance as a transatlantic forum, as a standing warden of Western security, or as a mere relic of different times.

The deterrent function of NATO is no longer needed. Moreover, the general push for quality over quantity is bound to affect the organization as well, likely in the form of rapidly deployable forces, rather than cumbersome bureaucratic mechanisms and bases across the continent. In these terms, the 2010 Strategic Concept8 emphasized NATO’s renewed role in modern challenges but brought about little changes.9 From the European citizens’ perspective, NATO is a body without a purpose in times of peace and disengagement, often forgotten when it is not active in military operations. As such the organization is facing severe communication issues, in positioning itself as reliable, authoritative and effective institution in the area of security and defense. In these terms, a strategic partnership with the EU would enhance its effectiveness, provide low-cost instruments and structures, and enhance NATO’s standing as an actor in the transatlantic setting, rather than a standing secretariat for setting up of multinational forces.

The European Union, as noted above, is also facing several issues due to the crisis, general skepticism of citizens and member states, and a period of transition to new leadership in 2014. Moreover, relations between DoS, the EU, and the White House are barely noticeable. Internally, the EU has yet not revised its Security Strategy (EUSS)10 since 2008.11 A Maritime Security Strategy should be issued at the end of 2013, when also the European Council (the periodic meetings between the Head of States of the Member States deciding the general policy guidelines for the Union) should discuss the 2020 objectives and general EU policies. Moreover, the current European leaders have missed several opportunities for improving the Union’s standing in the area of security. The creation of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy position, empowered also as Vice President of the Commission,12 was supposed to boost the effects of a Common Defense and Security Policy (CDSP), no tangible results have been produced so far. It is likely that when the current HRVP leaves office in 2014 the European CDSP efforts, especially in the form of a EUSS, will be approached differently and with more assertiveness.

As for EU-NATO partnerships, so far not much has been accomplished. The institutions tend to cooperate in practice (for instance in Somalia), but there is a severe lack of coordination in Brussels, where the institutions generally tend not to engage with each other. It is in the interest of the EU to strengthen its partnership with NATO, and in the interest of the U.S. to help implement this rapprochement, involving more actors in the Alliance and relating to the EU and NATO mainly in terms of security partnerships – at least at the organizational level. In terms of security strategy, both NATO and the EU are facing issues over properly representing the will of their state’s citizens and criticism for lack of effectiveness, so don’t expected too much in terms of actual involvement, more is likely on the side of formal partnership agreements.

The current European security situation is particularly static at the moment, mostly waiting for fundamental policy changes brought about by the combination of the European 2014 elections and upcoming high-level political meetings. Moreover, expectations for the 2014 QDR are lowered by the uncertain internal situation and more pressing local issues, namely the economic crisis and growing unrest for unpopular austerity measures. It is indicative, after all, that the most relevant regional documents in terms of security strategy, both for NATO and the EU, are reviews of concepts of the last decade. Even on those terms, many European countries remain extremely favorable to U.S. security objectives and will continue to constitute the staunchest allies for the U.S., and the 2014 QDR will definitely affect their future strategic concepts and policies.

Matteo Quattrocchi holds a LL.M. from Georgetown Law as well as a Master’s Degree in European and International Law from Luiss in Rome, Italy. He is currently a Junior Researcher at the European Institute for Asian Studies, after having worked in the NGO and private sector and taught in Rome and Washington, D.C. He is specialized in International and National Security Law and Policies, EU-Asia Relations and Maritime Security Law and Policies.

————————————————————————————————————————-

1. Benjamin Weinthal, Home Alone, Foreign Policy, 24 September 2013, retrieved from http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2013/09/23/home_alone_germany_angela_merkel_foreign_policy.

2. Center for Strategic and International Studies, European Defense Trends 2012, December 2012, retrieved from http://csis.org/publication/european-defense-trends-2012.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Supra note 1.

6. For more information please visit http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/ict/key_technologies/

7. Center for Strategic and International Studies, Preparing for the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review, March 2013, retrieved at http://csis.org/files/publication/130319_Murdock_Preparing2014QDR_Web.pdf.

8. NATO, Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization 2010, Lisbon, 19-20 November 2010. Retrieved from http://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/pdf/Strat_Concept_web_en.pdf.

9. Istituto Affari Internazionali, Swedish Institute of International Affairs, Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, Center for Strategic and International Studies , EU-U.S. Security Strategies. Comparative scenarios and recommendation, February 2013, retrieved from http://csis.org/publication/eu-us-security-strategies.

10. European Union, European Security Strategy, December 2003, retrieved from http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/78367.pdf

11. European Union, Report on the Implementation of the European Security Strategy – Providing Security in a Changing World, December 2008, retrieved from http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/reports/104630.pdf

12. While the High Representative is the head of the European External Action Service, the European version of the Department of State, he or she is also the Vice-President of the Commission, the main executive branch of the Union, thus putting the HRVP in the position of coordinating foreign and internal policy.

Bonfire of the Inanities

This article is a part of The Hunt for Strategic September, a week of analysis on the relevance of strategic guidance to today’s maritime strategy(ies).

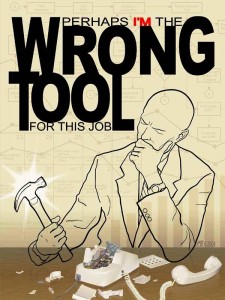

Sometimes you are forced by calendars and cycles to pop out a strategic document, or refresh a slightly stale loaf of intellectual effort.

Other times you can find yourself at a natural inflection point where it not only makes sense to re-evaluate your strategic requirements, but it is a necessity. Now is one of those times.

The bold-faced items which are screaming for attention are rather simple, but only on paper. They are actually exceptionally complex systems on their own, but they are shaping both our present and our immediate future.

1. The Long War is Over; Long Live the Long War. The American people, their elected representatives, and their nation’s allies have made it clear that after a dozen years of mostly low-intensity war, they want to trend back towards the mean. Nice thought, but the enemy gets a vote and we probably won’t be able to let the Olympics and World Cup be the place where nations, religions, and ideologies work out their differences.

That being said, the odds of over a hundred thousand American soldiers on the ground in some quasi-developing nation any time soon is small. Nation building in general will not be fashionable again for a generation. What we will need on very short notice with global reach is to find bad guys, break their stuff, and kill their people. We need to be ready to do that on our own – and have that robust capability for the foreseeable future and beyond. Long SOCOM, short NATO.

2. The Western Welfare State is Well Beyond its Design Limit.

“It is an undeniable reality that in today’s network and information society people are both more assertive and more independent than in the past. This, combined with the need to reduce the budget deficit, means that the classical welfare state is slowly but surely evolving into a participation society. … Achieving a ‘prudent level of public debt’ … is and will remain crucial. … If the debt grows and the interest rate rises, these payments will put more and more pressure on our economic growth, on the affordability of public services and on people’s incomes. … Unless we do something the budget deficit will remain too high. The shift towards a participation society is especially visible in our systems of social security and long-term care. In these areas in particular, the classical post-war welfare state produced schemes that are unsustainable in their present form and which no longer meet people’s expectations.”

“It is an undeniable reality that in today’s network and information society people are both more assertive and more independent than in the past. This, combined with the need to reduce the budget deficit, means that the classical welfare state is slowly but surely evolving into a participation society. … Achieving a ‘prudent level of public debt’ … is and will remain crucial. … If the debt grows and the interest rate rises, these payments will put more and more pressure on our economic growth, on the affordability of public services and on people’s incomes. … Unless we do something the budget deficit will remain too high. The shift towards a participation society is especially visible in our systems of social security and long-term care. In these areas in particular, the classical post-war welfare state produced schemes that are unsustainable in their present form and which no longer meet people’s expectations.”

– Willem-Alexander, King of The Netherlands, speech from the Throne, 17 September 2013.

Our traditional European allies and Japan are either creaking under the weight of unsustainable budget obligations, national debt, are too small, or have decreased military spending to the point of irrelevancy outside of auxiliary status as part of a larger nation or coalition action. Some combine all of the balance above; the United States is batting .500.

Until the Western economic model morphs in to what comes next and debt loads return to sustainable levels – at least a generation to fix – the last 100 years’ assumptions about the ability of nations at general peace to have armies sustainable in the field for any length of time are no longer valid.

3. Demographics, Resources, & Striving to Catch Up. In line with the changing reality of #2, populations in Europe and East Asia will begin to collapse along the Russian model in the coming decades. Folded in are the asymmetric demographics of ethnic/religions minorities within the European nations and Russia. When non-assimilated ethnic/religions minorities have roughly twice as many children as the legacy/host ethic/religions culture, history shows this leads to conflict. History belongs to those who show up, and numbers matter. One cannot expect to rely on “Cooperative Strategies” and “Global Fleets” when those nations that should be aligned with you cannot effectively deploy and have their largest security concerns internal to their borders.

In places such as Egypt, Yemen, and sub-Saharan Africa, population growth will continue to strip away per-capita improvements that should result from economic growth. Those nations, especially in a global information environment, will not be able to supply their people a sufficient standard of living, much less give them an opportunity to get close to the lifestyle they see every day via media.

As a result, migration challenges that we see on Europe’s Mediterranean coastline, eastern Siberia, and Western Australia will continue and expand to other areas. The target nations will have enough difficulty taking care of the hangover from the Welfare State and already existing unassimilated and growing minority populations to ignore this challenge. To add stress to the global system, they will soon become even more restrictive toward economic- and even conflict-driven migration.

To meet these three global drivers, what our nation needs in 2014 is a blank-paper, baseline review of the fundamentals; an existential strategic assessment of what our nation needs, what it wants, and what is aspires to be. It then needs to see what kind of military it can afford to meet somewhere on the line from need-want-aspire. What risks are worth taking? What requirements are non-negotiable?

Will we get such a strategic level review that we need from The Strategic Choices Management Review (SCMR)? Hard to say.

What direction and guidance will or did come from the political level to drive that strategic review? We simply don’t know. There is another 3-legged stool that I would offer for any such review that can guide those pondering once the political guidance is received, or any follow-on studies or policy documents are finished.

1. Know your place. This is at the strategic level. Most people are more comfortable slipping in to what they know best, the tactical or operational. Back away, think in broad strokes. If you have C2, C4ISR, or pictures of some Joint/Combined vignette in your document, you’re doing it wrong.

2. Embrace uncertainty. We have no idea what will be the greatest threat to our nation at the strategic level. We can have short lists. We can have most likely and most dangerous, but we cannot give anyone 51% certainty that we know where the next punch is coming. As a matter of fact, if someone in the room says they can tell you – assume they are wrong until other information backs them up. Uncertainty requires flexibility both intellectually and materially. Keep that at the top of your notepad. In an uncertain world, excessive speciality always leads to extinction.

3. Advertise your ignorance. It is OK to say, we have no idea. It is OK to say it is anyone’s guess. What needs to be done is to assess and mitigate risk. Be brutal with your assumptions and even if you are comfortable, have an answer if one of them is wrong. If your answer requires pixie dust, you’re doing it wrong.

When thinking about strategy, the maritime wedge has two reference points most think of; there is “The Maritime Strategy” from 1986, and the 2007 “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower.” Both were products of their time, and in 2013, as templates, both should be thrown aside. Like I said, blank paper.

Who should be writing our next national defense strategy? If we built our team as usual, we will get simply a conventional wisdom, jargon-filled, programmatic-defending, and buzzword-filled work that will be quoted a lot, read less, and almost never fully understood.

Who should be writing our next national defense strategy? If we built our team as usual, we will get simply a conventional wisdom, jargon-filled, programmatic-defending, and buzzword-filled work that will be quoted a lot, read less, and almost never fully understood.

If we looked around the table (virtual or actual) at the first meeting of those who will have a major say in the document and half the people are over 50, we are not starting right. If at least 20% of the people are not under 30, we are not starting right. If more than half were STEM graduates at the undergrad level, we are not starting right. If the majority were known as team players and “company men,” then we are not doing it right.

Odds are however, that the group writing our strategy will be mostly over 50, spent most of the last decade and a half within commuting distance of The Pentagon, are from technical backgrounds, and are recidivist staff weenies of one kind or another. They also will be given way too much time to complete their study.

What I am interested in is if there will be a “Minority Report” of any kind. The group’s evil twin Skippy – their other-universe Spock sporting a goatee and looking askance at all that seems slightly off. Will there be a COA-A and a COA-B for public debate?

What I am interested in is if there will be a “Minority Report” of any kind. The group’s evil twin Skippy – their other-universe Spock sporting a goatee and looking askance at all that seems slightly off. Will there be a COA-A and a COA-B for public debate?

I don’t think so, but we should. This is how I would do it.

What if we formed a fast and loose second group to offer their view of what our strategy should be? One where 75% were under 50? 50% under 35? Get a grumpy, terminal 06 with a liberal arts PhD to round up a gaggle of iconoclasts. You know the types; those who gave the middle finger to their community-fill and pursued a resident PhD program or quirky fellowship. The ones who caused their bosses to get “the call” late one afternoon because one of their officers decided to write something for publication with a message way off the reservation. The historian. The fiction writer. One of the sociologists who was on a human terrain team in AFG.

Keep the group relatively small compared to the “official” group. Most important, have it work outside FL, CA, WA, HI, VA, and MD. Better yet, ship them off to an ICBM command silo in South Dakota. Give them a little “The Shining” vibe to their deliberations.

Keep the group relatively small compared to the “official” group. Most important, have it work outside FL, CA, WA, HI, VA, and MD. Better yet, ship them off to an ICBM command silo in South Dakota. Give them a little “The Shining” vibe to their deliberations.

Give them a charter such that “Point 1” is that under no circumstances will they contact anyone in the official group. “Point 2” should be that within 3 hours of their first meeting, they have to select their Chairman. The person who formed the group not only cannot be the Chairman, he cannot be involved in any of the deliberations as a member either. Yes, no one will appoint the Chair, the members will vote on him. They will also set their own rules of order. They have 2 hours to do that.

As South Dakota has terrible per diem and people have other lives to live, another advantage would be that they would be motivated to get their work done quickly and in a digestible format.

Their report will not be chopped by anyone, and all members must sign the final document. Each member, if they wish, will be allowed a 1-page 10-pt font opportunity to outline any additions to or deletions from the report they would prefer. Consider it a Minority Report nested inside a Minority Report.

As their report would most likely be completed before we see the official report, it would be embargoed and in possession of the Chair until the day the official report is made public record. Heck, the way things are going, we probably still have time until the SCMR report comes out.

Their broader charter is not to pick the most outlandish or radical strategy, or to be avant-garde for the sake of being avant-garde – but to offer what they see as the best strategy.

If their results are close to the official report, then all the better – we may be close to where we need to be. If not, well even better – creative friction!

Would such a process potentially undermine the official strategic document? Perhaps, but so what? The purpose is to promote debate about the direction we need to take as a nation – not predict the future. It only becomes a negative if we let it. As no one knows the future, what harm would there be to an addendum to the strategic document titled, “An Alternative View?”

None. What good will it do? Tremendous good in encouraging a broad range of thinking about what our nation is, what it should be, how we should go about pursuing that aspiration, and how we should man, train, and equip its armed forces to support that pursuit.

Well, that is the theory, and we are talking about something soaked in DC … so … yea.

Budget-Driven National Defense Strategy

This article is special to The Hunt for Strategic September, a week of analysis on the relevance of strategic guidance to today’s maritime strategy(ies).

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) Pub 1-02 defines the term “Strategic Concept” as: “The course of action accepted as the result of the estimate of the strategic situation. It is a statement of what is to be done in broad terms sufficiently flexible to permit its use in framing military, diplomatic, economic, information and other measures which stem from it.” The government’s estimate of the strategic situation can be found in the National Intelligence Council publication: Global Trends 2030 Alternative Worlds, December 2012. [1] The course of action is reflected in the President’s 5 January 2013, defense strategy guidance entitled: Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense. [2] Known as the DSG, this guidance was intended to serve as the basis for DoD policy and resource decisions based on projected fiscal constraints. However, the DSG did not include the significant additional cuts triggered by the Budget Control Act, e.g. “sequestration.”

The Strategic Choices and Management Review (SCMR), commissioned by the U.S. Secretary of Defense, was designed to produce guidance to the DoD to deal with the sequestration in 2014; formulate budgets for 2015-2019; and, serve as the basis for the upcoming Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). On 1 Aug 2013 Secretary Hagel announced the findings of the SCMR and laid out two alternative paths. One path would prioritize high-end capabilities over end-strength. The other would keep end-strength but sacrifice modernization and research and development on next-generation systems. In summary, the world situation is well-defined in the DNI’s Global Trends 2030 Alternative Worlds (footnote 1). However, the strategy or course of action for national defense planning and programming is a mess given the certainties (or uncertainties) of fiscal levels resulting from sequestration. For Congress, the question is which comes first: the national defense strategy (the chicken) or the funding levels (the egg)? Clearly the egg is in charge.

The QDR, mandated by Congress, is to be conducted by the DoD every four years to examine force structure, force modernization plans, infrastructure, and budget plans. The QDR is supposed to be a comprehensive effort to prepare a national defense strategy looking forward 20 years. Logic would argue that if the national security threat is well-defined and understood, the strategy for addressing that threat would come first, with fiscal constraints causing adjustments to the strategy in areas of least risk. The threat is projected thru 2030 and available to Congress. The President has issued defense strategy guidance priorities for the 21st century which are available to Congress. So, why does Congress require a QDR that, in effect, duplicates the executive branch processes? Surely the congress understands that the DoD QDR has to be consistent with the President’s defense strategy guidance and consistent with the President’s budget submissions for DoD.

As presently defined, the QDR requires a substantial effort, delivers little value, and should be terminated.