By Claude Berube, PhD

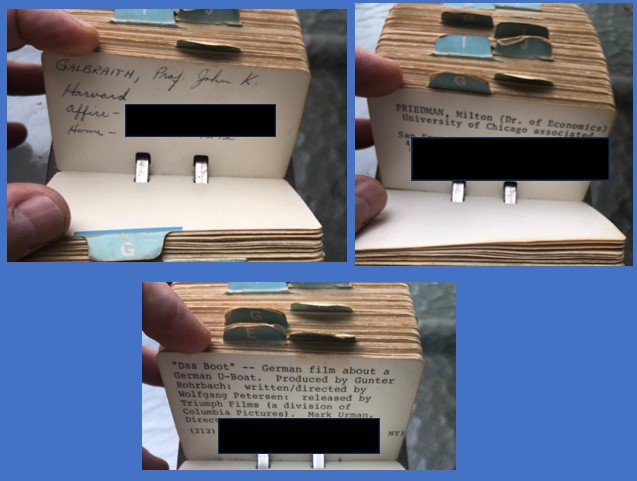

With nearly a dozen biographies, countless articles, and word-of-mouth stories, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover may be the most written- or talked-about flag officer in US naval history. Can we still learn anything about the man, what he did, or why he did it? Beginning in the 1950s, many authors and publishers approached Rickover about a biography or autobiography – Simon & Schuster, Harper & Row, Naval Institute Press, etc. He rejected them all, wryly noting that “autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.” Dr. Francis Duncan, a historian working for Atomic Energy Commission, eventually wrote two authorized biographies based on more than a decade with Rickover, as recorded in copious notes. Duncan also had the advantage of having access to the most substantive collection of Rickover papers. Rickover was a master of shaping his image; consequently, an authorized, contracted biography with Duncan offered the best opportunity for him to manage that story.

Historian Barbara Tuchman wrote that historians should use primary sources only because secondary sources have already been pre-selected and that one should read two or three versions of any episode to account for bias. Such is the case with every Rickover biography. When in 1983 a columnist from The Washington Post asked Rickover to write a biography, the Admiral explained that he had already compiled volumes of his thoughts and reflections on various subjects over the years and that he did not want to condense them into a book. However, he did allow that perhaps someone else may decide to do that someday. That was what Duncan had access to and is now finally available to researchers.

Retained in Rickover’s Arlington condominium until his second wife Eleonore’s passing in 2021, the collection was bequeathed by her to the US Naval Academy. They were then catalogued and made available in the Nimitz Library’s Special Collections and Archives. Rickover’s papers include personal correspondence, memoranda from meetings with journalists, congressmen, admirals, and presidents, as well as transcripts of telephone conversations and the famed interviews with applicants of the nuclear program. This totals approximately 250 archival boxes, arguably one of the largest collections of any U.S. naval officer.

Perhaps the most insightful and significant papers are the daily letters to and from his first wife Ruth in the decade leading up to the Second World War. This is the real education of Hyman G. Rickover – researchers will learn how he shaped himself and, more importantly, how he was influenced by Ruth.

Researchers will find plenty on the recommendations and behind-the-scenes decision-making of major programs throughout the Cold War, all thanks to Rickover who left such incredibly detailed records. The papers will confirm the mythology and stories about Rickover all these years; but it will also surprise many people. There are other aspects to the man and the officer.

He received thousands of fan mail letters from home and abroad. He was as likely to get a note of thanks from a teacher in Chicago, a student in San Francisco, or a young adult in Ghana, as he would from a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee or president of a major corporation. He was recognizable – he was, for example, one of the few Navy admirals to grace the cover of Time magazine after World War Two and television talk shows sought him out because of his outspokenness and appeal to the broader public.

Rickover succeeded by his intellect. He was driven by curiosity and learning what he did not know. He was a voracious reader even on his early ships and submarines trying to understand the world around him. Among those literally thousands of works were Michael Ossorgin’s Quiet Street, Captain Robert Scott’s letters on his voyage of discovery to the South Pole, Boris Pilnyak’s The Volga Falls to the Caspian Sea, Karl Marx’s Das Capital, and Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Readers may be surprised that Rickover, a Polish-Jewish emigre, would read this notorious work, however the answer may lie in the fact that Rickover read articles and books not to agree with them but to understand the ideas shaping the world both negatively and positively. Another factor may have been understanding his first wife Ruth’s country of origin better and communicating with her as he saw her as not an intellectual equal but his intellectual superior. Rickover, never one to do anything by halves, taught himself German in order to translate a book on U-Boat tactics.

He faced personal challenges. He was self-aware enough as a junior officer that he could admit to his young wife Ruth his sudden fits of depression and despair and being tormented by the “slough of despond.” He later admitted to his official biographer that he suffered from an inferiority complex. Perhaps these were simply part of what drove him to succeed and surpass his peers in some ways.

Rickover held integrity as one of the highest character traits. He could not be compromised. During a meeting with his friend the British Lord Mountbatten, Rickover was offered a knighthood in exchange for an agreement on submarine information, resulting in Rickover returning to the dining room his face “pale with anger.” On their way home, he told his second wife Eleanore the story and concluded with, “Can you believe he didn’t know me any better than this – that I would fall for a knighthood?” True to Eleonore’s nature, she responded, “But I’ll always be a Lady.”

He challenged elitism everywhere – the Navy, large defense contractors, economic classes – likely because he had risen from a childhood of such poverty that his mother could only afford an orange once a year in Poland. He was acutely aware of his role and his destiny in the Navy, not simply as Hyman Rickover, but as someone who had arrived in the United States with nothing and whose religious background might have been an impediment at the time. As he told his biographer and preserved in countless notes made by Duncan, “My job, as I saw it, was to struggle through to the greatest accomplishment of which I was capable, ignoring, as far as possible, my Jewishness. This is not to say that I denied it. What I denied was the power it had to limit self-development, to force me to act humbly, rather than arrogantly, to suffer.”

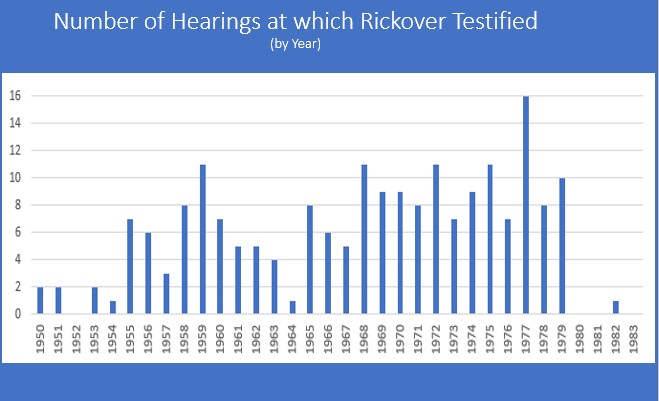

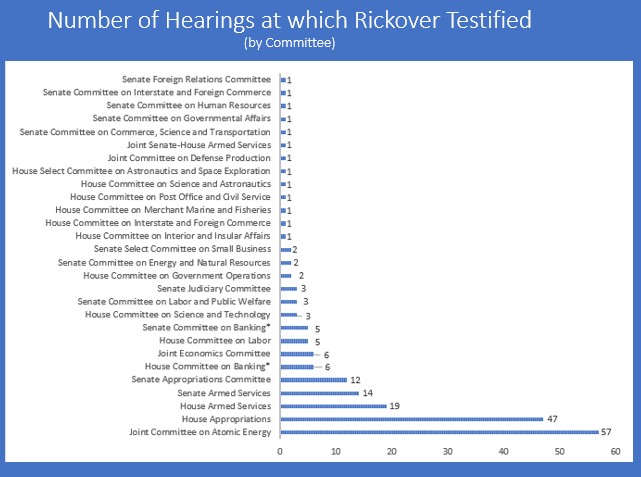

No factor contributed more to enabling Rickover’s successful career than Congress. A student of history, he realized that the Royal Navy’s Admiral Sir Jackie Fisher made political connections as a young officer and, consequently, it was easier for him to make reforms, a discussion that occurred between Rickover and his friend Lord Mountbatten. He knew how to cultivate support among members – by giving them the information they asked for and having a reputation for efficiency. He was idolized and befriended by members of Congress. Over the course of four decades, he testified before congressional committees more than two hundred times – a record likely unsurpassed by any military officer or civilian.

Rickover spoke to them in hearings, and in personal conversations, in ways no other military officer could or would dare. He was honest, direct, and, yes, he could entertain them with his sharp wit even in a hearing that would never occur in the 21st century. They loved him for it. They respected his technical expertise, but they also expected and valued his candor. For some, he became their friend “Rick.” Rickover notes attending DC plays with Senator Scoop Jackson and their wives or dining at the home of House Appropriations Chairman Clarence Cannon who played the piano for him. Rickover’s influence, reputation, and relationships with senior congressional leaders was such that he would be called to answer off the record questions or when some members needed help. In one case, Congressman Charles Price wanted to see House Appropriations Chairman Cannon who was not seeing anyone. Price appealed to Rickover to intervene. Cannon, upon Rickover’s request, acceded and met with Price. And it was an intervention by Congress, not the Navy, which would promote him to flag rank.

In his early years as an admiral, the Navy brass and a Secretary of Defense tried to temper Rickover’s influence with Congress to no avail. As one admiral noted after a conference in Monterey of flag officers on the Rickover problem, “there isn’t a damn thing we can do to him or about him, because he’s got the Congress on his side, and we’d just better live with it.”

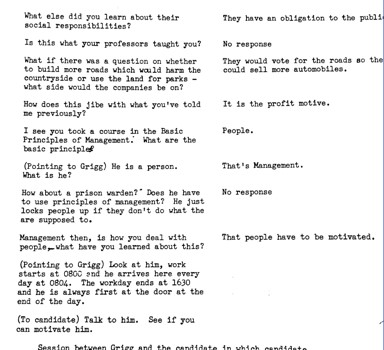

Most in the U.S. Navy’s submarine community have heard the stories of the famous Rickover interviews, where he would place the midshipmen in uncomfortable situations or berate them to determine how they could respond to adversity, but now aside from the experiences of those young midshipmen, we now have concrete evidence. Actual transcripts of many of those interviews exist in this collection. His reputation was cemented by the famed “interviews” of midshipmen applying – or in many cases told to apply – to the nuclear reactor program. Rickover required some candidates to have their parents or fiancées write letters on their behalf understanding why the midshipman would have to sacrifice time away from them (again, the letters of which are in this collection). Perhaps it was because the Navy had refused Rickover’s own request as a junior officer for a specific billet to accommodate Ruth in her career.

The interviews, as well as his speeches and memos, make it clear that though he was involved with and promoted technology, he placed a higher value on the humanities. As he questioned the midshipmen, he would discuss history, philosophy, religion, and management and not their technical skills. He writes that he can train anyone for the nuclear program but they had to be able to think and the humanities offered the best grounding for those future officers.

Rickover gave and wrote hundreds of speeches. His first known speech was in 1931 on the topic of the World Court to the Portsmouth, New Hampshire Kiwanis Club. Later that decade he spoke to technical organizations. His speech to a wider audience, “The Importance of Education in the Advancement of our National Resources,” occurred in 1953. Soon after, he was frequently invited to speak to a variety of organizations domestically and internationally. Rickover’s speeches were a breadth of practical, philosophical, and governmental issues: “Thoughts on Man’s Purpose in Life,” “Competency Based Education,” “The Decline of the Individual,” “An Effective National Defense,” “The Meaning of a University,” “Liberty, Science & the Law,” and “A Humanistic Technology” are just a few. On average, he gave at least one speech monthly. Education would be his obsession – in addition to the nuclear navy which he saw as inextricably intertwined.

He could be curt, rude, and abusive to officer candidates for the nuclear power program, to the point where the Chief of Naval Operations gently asked him to reconsider his methods. On the other hand, the papers show he could engender such loyalty from his technical and administrative staff that many stayed with him throughout his tenure as he fathered the nuclear navy for three decades. The internal office memos written by Rickover to his staff or his sharp wit to Senators and Members of Congress during congressional hearings are insightful.

People are often more complex than perceptions. The papers clearly demonstrate that Rickover had an unexpected compassionate streak. He helped his staff when they needed to move to a new assignment and would loan them money to purchase a new home; he voraciously wrote get well notes to people he knew, especially if they were children of friends. All the money he made from speeches, articles and books was donated to charities such as orphanages, disabled children societies, CARE, etc. In Shanghai as the Japanese invade China, Rickover stopped to tend to the poor and dying on the streets. One letter is from a young boy named Hyman from California taunted at school for his name and was told by his mother that there was an admiral with the same name. Rickover responded to him, explained to him the history of the name, and gave him advice. In all of this collection, Rickover only signed “H.G. Rickover,” except in this case where his empathy led him to sign his name, “Hyman Rickover.”

These papers represent a new era for understanding Rickover, the Navy, and the nation. These papers should eventually be made public so that Rickover might be known on his own terms and uncensored, even decades after his death. There is more work to be done, and I hope some historians will explore those papers. There are dozens of books to be written and, perhaps someday, a full transcription of all these papers will be completed.

Claude Berube, PhD, is a history professor at the US Naval Academy and former director of the Naval Academy Museum. He and archivist Samuel Limneos edited a volume of a portion of the Rickover papers, Rickover Uncensored, published in October 2023.

Featured Image: Admiral Hyman Rickover. (Photo via Naval History and Heritage Command)