By Javier Guerrero C.

Last year, the Colombian Navy detected and captured the first electric narco-submarine.1 Demonstrating the innovative capacities of Colombian drug traffickers, narco-submarines, drug subs, narco-semisubmersibles, self-propelled semisubmersibles, or simply narcosubs, are maritime custom-made vessels used principally by Colombian drug traffickers with the purpose of smuggling illicit drugs to consumers or transshipment countries. This year only one of such vessels have been captured, and given their technical characteristics seems a step back in the ‘evolution’ of narcosub technology. Such is the paradox of security and maritime interdiction in the War on Drugs. The very process of thwarting a particular method or route creates the conditions to propel technological innovation on the drug traffickers’ side. The narcosubs are one of many of these innovations.

The term “narcosub” encompasses a diversity of watercraft that includes semisubmersible and fully submersible vessels. Several entries on CIMSEC (here, here, and here) have already delved into the characteristics of the narcosubs and their potential capacities to threaten regional security. In addition, several studies in the security field, such as by Ramirez and Bunker,2 as well as academic articles, have also attempted to provide technical evidence and policy advice. To summarize, narcosubs are characterized by the use of maritime diesel engines, a rudimentary system of refrigeration, no facilities, fiberglass hulls, and a valve which can be activated in case of being captured that allows water to fill the hull and sink the vessel. Narcosubs are not made to last, as smugglers mostly discard such vessels after ending their one-way journey. Smugglers have been using narcosubs from at least as early as 1993, but the majority of captures have been made since 2005. Narcosubs are described by the Navy as vessels that are highly difficult to detect and/or track, due to their lack of emissions, small wake, and low heat signature, preventing visibility all around.

Despite the centrality of innovation in the War on Drugs, there have been few attempts to understand the process. Given that 90 percent of the cocaine from Andean countries is transported using maritime routes,3 it is necessary to analyze the development of drug trafficker and state agency technologies in the maritime environment. That is to say, the study of the game of cat and mouse between interdiction and evasion.

This binary can be understood as the symbiotic relationship that creates the conditions for innovation, generating a constant arms race between drug traffickers and state agencies. Different versions of the genesis of the narcosubs mill around, from Pablo Escobar’s mastermind idea, boosted by the semi-mythical image of the drug baron with the economic means and savvy to contract specialized naval engineering. According to this

version, Pablo Escobar supposedly conceived the idea of a submarine after watching a James Bond movie. In this story a Russian and an English engineer were hired to design the submarines while Pablo’s brother took took care of the electric circuits.4 A common narrative in describing narcosub building is to assume some form of hierarchical organization, both in terms of decision making and knowledge. That is, the participation of a ‘cartel’ with capabilities to hire ‘expert knowledge’ such as naval engineers who then recruit builders. The diffusion of the technology is also assumed to be the result of transnational organized crime networks. Others suggest that narcosubs are the transfer of military innovation by the guerrilla groups FARC or ELN to their drug trafficking enterprises.5

Innovation in the design and building of these vessels is so commonplace that the adjective ‘first’ is often repeated. The truth about narcosub design and building may be more prosaic. The variety of watercraft labeled under the banner of narcosubs summarizes some of the key features of the innovation and counter-innovation competition in the War on Drugs.

The Evolution of Narcosubs

The narcosubs demonstrate a variable combination of materials, designs, and building. Even narcosubs found in the same shipyard vary in several features. In this sense, each narcosub is a unique way to solve the problem of transporting large amounts of illicit drugs, producing a complex timeline that is problematic to define using traditional innovation concepts, such as incremental or radical innovation, but also to define as the result of pull/push factors. The process of innovation in the War on Drugs can be better described using the concept of dispersed peer innovation,6 in which the design and construction of these vessels, not being bound by standardized procedures, profits from the possibilities of creating their own designs with high degrees of flexibility. In this sense, it is possible to say that what smugglers produced with the narcosubs are different versions of a ‘techno-meme’ that gets combined with the local knowledge of maritime routes and boat building. Those involved in the process of outlaw innovation are able to mix locally available knowledge of traditional boat building with off-the-shelf technologies.

One key issue when studying the evolution of narcosubs and other forms of drug traffickers innovations is how entwined they are with other forms of maritime drug transport. The process of incremental innovation does not necessarily produce a particular method that replaces older strategies. For example, a technical analysis of improvements of the go-fast boats or fishing boats demonstrates that there are few steps between semisubmersible methods and submersible ones. These few steps are provided by the availability of the knowledge to build such vessels within the relatively small areas where narcosubs can operate.

What it Takes to Build a Narcosub

Little is known about the day-to-day decisions on design and modification of such vessels. Official documents say little about the narcosub builders, but a set of documents allows us to take a glimpse at the organization of a narcosub enterprise. These include the Supreme Court of Justice ruling on the extradition of Colombian nationals to the United States in order to be judged by courts in the U.S. for criminal offenses, including narcotics violation, and reports from the law enforcement agencies and military.

Several facts can be derived from the analysis of such documents. Narcosub builders are often independent of the owners of the cocaine. Several opportunistic relationships are undertaken, with drug traffickers either contacting the builders or the builders contacting the drug traffickers. As part of a plea bargain, a narco-submarine builder narrates how as a part of his organization he carried out and presented blueprints of ‘his’ narcosubs, and descriptions of the areas where the vessels could be built and launched. As part of his negotiation with prospective buyers, he shared his past experience of success in the building and operation of these boats.

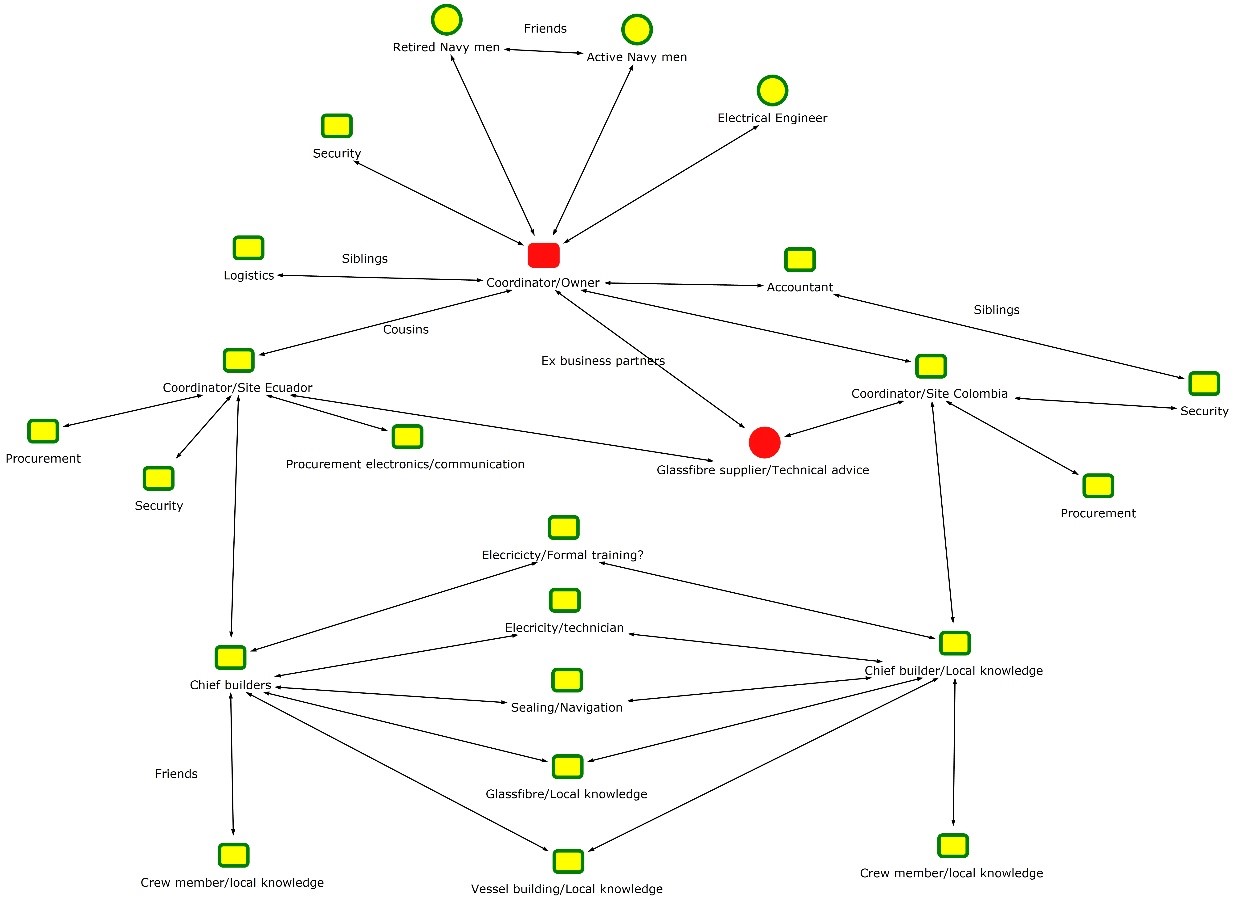

Figure 1 reconstructs the main links in a narcosub builder organization and shows the multiple forms of knowledge and relationships that can be found in such an organization. While some aspects of the design are carried out by specialists such as electrical and mechanical engineers, others are left to people with local knowledge, such as knowledge about fiberglass handling and coating. In this organization, another individual, the provider of the fiberglass, also plays the role of quality assurance guaranteeing that, in fact, the vessel is correctly waterproofed. Other individuals are in charge of the logistics, such as the purchase and transport of materials and personnel to shipyards. Finally, some individuals are hired as crewmen. They test the vessel and provided feedback to builders.

The organization described in the legal files is interesting because it has two different construction sites; one in Colombia’s South Pacific and one on the Ecuadorian coast. The organization boss was not actually involved in the construction of the narcosubs, but he was the main source of finance. The main builder of the narcosubs is considered a “chief” within the organization. Besides providers of drugs, every shipyard has an administrator accompanied by a chief of security. The description provided does not delve into the process of designing and building narcosubs specifically, but shows the participation of people with formalized knowledge and others in possession of craftwork knowledge, such as the people involved in the woodworking and the fiberglass construction, some of whom worked in both shipyards. The fiberglass work was supervised by another specialist, who provided expert knowledge and supervision at both sites. This person was not part of the organization, but was the provider of the fiberglass. In the same organization, a mechanical engineer was identified, who was in charge of the design and building of the hatches, steering mechanisms, and galvanization of the narcosubs.

The innovation in narcosub technologies is then carried out by a multitude of different groups with little incentive to collaborate among themselves. This gives rise to a wide variation of submersible and semisubmersible designs. Such technical decisions are taken by builders and drug traffickers in a context in which the actions of other groups and their enemy (law enforcement and military) are not always known.7 Narcosub builders are able to configure a complex design using a mix and match approach. Blending off-the-shelf solutions, local traditional knowledge, and technical-formal knowledge produces hybrids such as low-profile narcosubs using truck diesel engines.

Drug smugglers do not just compete with the state, they also compete with other drug rings and other narcosub builders. This complex pattern of competition plays a role that promotes further local innovations. Through trial and error they master the building principles of the narcosub and introduce minor variations into their models. The variation and innovation in narcosub technologies, as well as the interpretation that actors, smugglers, and enforcement agencies make of such innovations, creates changes in a co-evolutionary fashion. In this way, the choices of the illicit actors, competing among themselves and against the state, continuously destabilizes and changes the landscape in which they act, triggering a situation in which multiple players attempt alterations, which create new adaptations.

Conclusion

It has been argued that smugglers often have the capacity to change their strategies and designs after they been detected by law enforcement and the military. Nevertheless, a more complex understanding of the pattern of innovation in the War on Drugs, in which explanations are not given in terms of push/pull between state agencies and drug smugglers, but take into account multiple layers of competition and sources of knowledge, will provide better tools to control the illegal flows. One main consequence of this would be to escape the fallacy of flexibility, in which the explanations of the process innovation in the War on Drugs is given solely based on drug traffickers’ actions.

Javier Guerrero C. is a Lecturer at the Instituto Tecnológico Metropolitano (Medellín, Colombia). In addition, he is a Post-Doctoral researcher at Centro de Estudios de Seguridad y Drogas, Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, D.C, Colombia). Javier is currently researching the intersections between technology, security and the War on Drugs and the history of technology in the War on Drugs. He may be reached at the following addresses: javierguerrero@itm.edu.co; je.guerreroc@uniandes.edu.co

Endnotes

[2] http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1029&context=cgu_facbooks

[3] http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1016658.pdf

[4] Escobar, R., & Fisher, D. (2009). The Accountant’s Story Inside the Violent World of Medellin Cartel. New York: Hachette Book Group.

[5] Jacome Jaramillo, Michelle. “The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Development of Narco-Submarines.” Journal of Strategic Security 9, no. 1 (2016): : 49-69.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.9.1.1509

Available at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol9/iss1/6

[6] Hyysalo, S., & Usenyuk, S. (2015). The user dominated technology era: Dynamics of dispersed peer-innovation. Research Policy, 44(3), 560–576. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.01.002

[7] http://revistas.flacsoandes.edu.ec/urvio/article/view/2943

Featured Image: A makeshift submarine is lifted out of the water at Bahía Malaga on the Pacific coast, in 2007. (Colombian Navy/Reuters)

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines.

On one side, drug cartels attempt to optimize their operational efficiency while mitigating the risk of detection, seizure, and capture. On the other side, we have law enforcement and militaries’ efforts to improve their surveillance and detection capabilities. This race to out-flank and counteract one another has led to the development of narco-submarines. This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.

This work is anticipated to appear in the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) website as unclassified research conducted on defense and security issues that are understudied or under-considered. The work contains a preface written by Dr. James G. Stavridis, and a number of essays written by U.S. Navy Captain Mark F. Morris, Adam Elkus, Hannah Stone, Javier Guerrero Castro, and Byron Ramirez discussing and analyzing narco-submarines. The paper also comprises a comprehensive photo gallery, arranged in chronological order, which allows the reader to observe the evolution of narco-submarine technologies. It also contains a cost benefit analysis of using narco-submarines, as well as a map and a table that highlights where these distinct narco subs were interdicted. The data that we came across seems to propose that cartels have been using different types of narco-submarines concurrently; hence, they seem to be employing a mixed strategy.