By Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy

The following is the first in a five-part series meant to shed light on Hainan Province’s maritime militia. For decades, these irregular forces have been an important element of Chinese maritime force structure and operations. Now, with Beijing increasing its capabilities, presence, and pushback against other nations’ activities, in the South China Sea (SCS), Hainan’s leading maritime militia elements are poised to become even more significant. Yet they remain widely under-appreciated and misunderstood by foreign observers. Read the introduction to the article series here, which offers a general background on China’s maritime militia and explains its growing importance.

Such lack of understanding is increasingly risky for U.S. policy-makers, planners, and military operators. This is particularly the case given recent, long-overdue American expression of determination to continue Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) in accordance with international law near Chinese-occupied and -augmented features in the Spratlys. As demonstrated by apparent maritime militia operations in proximity to USS Lassen when it sailed near Subi Reef on 27 October 2015, Beijing may well see maritime militia as a tool with which to make FONOPS increasingly uncomfortable for U.S. forces while carefully calibrating its signaling and avoiding undue escalation.

To help rectify this knowledge gap, we begin by introducing and analyzing maritime militia based in strategically-situated Sanya City, one of Hainan’s greatest naval, fishing, and maritime economic hubs. Prominent among Sanya-based maritime militia is the Sanya Fugang Fisheries Co., Ltd. (三亚福港渔业水产实业有限公司), founded in 2001. One of Sanya City’s major marine fisheries companies, Fugang Fisheries is composed primarily of Fujianese fishermen. A leading participant in both fishing expeditions to the Spratlys and harassment of foreign vessels there and elsewhere in the SCS, it has been celebrated for its bravery.

Indeed, among even the vanguard militia units profiled in this series, Fugang Fisheries is itself at the vanguard. That helps to explain why it has been entrusted with supporting so many Chinese operations, and involved in so many related international incidents, in the SCS. Fugang has dispatched its vessels and crews as maritime militia in service of China’s maritime security efforts in the SCS, primarily for “rights protection” (维权), efforts to advance and defend China’s island and maritime claims that are increasingly in tension with Beijing’s parallel objective of “maintaining stable relations” (维稳) with its immediate neighbors and the United States. Focusing on Sanya’s maritime militia, Fugang Fisheries first among them, thus offers disproportionate insights into an important element of Chinese maritime policy and activity with direct implications for U.S. interests, presence, and influence in the SCS.

Operations to Date

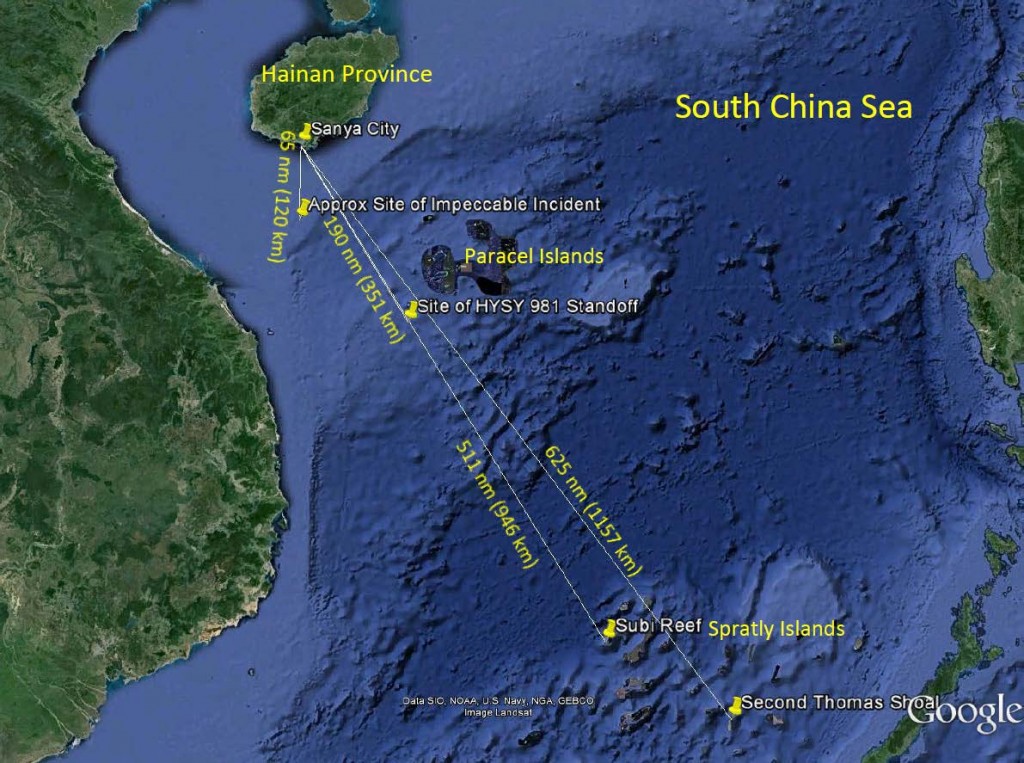

In recent years, maritime militia forces from Sanya, including Fugang Fisheries, have participated in several significant maritime incidents between China and the United States, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The location of these incidents, together with their respective distances from Sanya City, is depicted below.

Exhibit 1: Locations of Sanya City maritime militia operations in the South China Sea

Central Role in Impeccable Incident

On 8 March 2009, following several days of sporadic encounters, the ocean surveillance ship USNS Impeccable was surrounded by a group of five Chinese ships 75 miles (120 km) south of China’s Hainan Province in the SCS. The contingent included a People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) intelligence collection ship (AGI), a Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE) patrol vessel, a State Oceanographic Administration patrol vessel, and two small Chinese-flagged trawlers. Close-in harassment by the trawlers ensued. China is one of a small minority of nations that insists it has the right to regulate foreign military operations and other activities it deems detrimental to its security in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). One of the trawlers involved, hull number F8399, belonged to Fugang Fisheries. The fishing trawlers, although dwarfed by the Impeccable, were successful in disrupting the normal operations of the U.S. vessel. Lin Wei (林魏), owner of the company’s largest ship, is reported to have piloted trawler F8399 during the Impeccable Incident, facing down the U.S. crew and its use of water hoses. Lin and his crew’s actions made them famous amongst the fishing communities when they returned to Sanya harbor.

Videos of the Impeccable Incident may be viewed here.

Exhibit 2: Trawler F8399 attempting to grapple USNS Impeccable’s towed array cable in March 2009

Five years later, trawler F8399 was lost to a fire in late April 2014, catching ablaze while in harbor. Although F8399 was a noteworthy trawler, its loss is a drop in the sea amongst the numerous trawlers available in Sanya. This is particularly true as Hainan supports programs to replace old hulls with newer, more capable trawlers well equipped to travel to, and operate around, the Spratlys. As will now be explained, while trawler F8399’s owner Lin Wei lost one ship, he has gained another one that is far larger and more capable.

Exhibit 3: Vessel F8399 subsequently succumbed to a shipboard fire in late April 2014

Sanya Fugang Fisheries Co. has developed the ability to conduct fishing expeditions to the Spratlys, a journey of over 600 nautical miles (1111 km). Central to these efforts is its 2011 construction of F8168, a 3,000-ton fisheries supply ship owned by Lin Wei that doubles as a command ship for Sanya fishing fleets heading to the Spratlys. In July 2012, command and supply ship F8168 led a fleet of 29 trawlers and 316 fishermen on an 18-day expedition to the Spratlys, covering 1,756 nautical miles (3,252 km). Organized into two formations with three sub-groups each, the fleet operated around Fiery Cross and Subi Reefs, taking shelter from an approaching typhoon inside Mischief Reef’s lagoon. A dockside welcoming ceremony was held upon the flotilla’s return to Sanya Harbor, attended by Provincial Department of Ocean and Fisheries Director Zhao Zhongshe and Sanya City Mayor Wang Yong. The event celebrated the success of Fugang Fisheries’ efforts to combine with two of Sanya’s fishing collectives into one large fleet. Officials lauded the fleet’s ability to increase both the safety and the scale of operations thanks to command and supply ship F8168’s providing the rest of the fleet with fresh water, fuel, and ice; and purchasing and storing trawler catches on-site. During one of the fleet’s more recent voyages to the SCS, it conducted fishing operations in the Spratlys for more than 40 days, demonstrating improved ability to sustain continuous fisheries production and longer-term presence in disputed waters.

Exhibit 4: F8168 returning with 29 trawlers from the Spratly fishing grounds in July 2012

Accompanying the Fugang Fisheries-led fleet’s pioneering July 2012 voyage was the electronically-sophisticated Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE) Cutter YZ 310 (also known as 渔政310, or FLEC 310), the same ship that confronted the Philippine Navy at Scarborough Shoal just a few months earlier. As Ryan Martinson of the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute explains, “Despite their many pressing missions, the national-level Fisheries Law Enforcement units procured very few new ships in the years leading up to the [establishment of a unified China Coast Guard (CCG) in 2013.] One noteworthy addition was YZ 310, a very advanced, large-displacement (2,500 metric tons) ship delivered in 2010. Although based in Guangzhou, this ship has performed rights protection operations as far north as the Senkaku Islands and as far south as James Shoal in the SCS. It appeared at Scarborough Reef in April 2012, during the standoff with the Philippines. It was also involved in a tense confrontation with Indonesian Coast Guard vessels, in which it may have used jamming equipment to intimidate its victims.” One noteworthy addition was YZ 310, a very advanced, large-displacement (2,500 metric tons) ship delivered in 2010. Although based in Guangzhou, this ship has performed rights protection operations as far north as the Senkaku Islands and as far south as James Shoal in the SCS. It appeared at Scarborough Reef in April 2012, during the standoff with the Philippines. It was also involved in a tense confrontation with Indonesian Coast Guard vessels, in which it may have used jamming equipment to intimidate its victims. From Scott Bentley’s detailed analysis of the same incident, it “appears highly likely that during that incident Yuzheng 310 jammed the communications of the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (KKP) vessel Hiu Macan 001.” As with the circumstance of Chinese vessels teaming up for the Impeccable Incident, YZ 310’s involvement in Fugang Fisheries’ Spratly expedition further illustrates the sophisticated, wide-ranging coordination of China’s maritime forces.

Assisted by four FLE personnel aboard command and supply vessel F8168, YZ 310 escorted and commanded the fleet. This was especially important because of the relatively new nature of this operation. Fortified with a variety of subsidies to promote fishing in the Spratlys, and protected by FLE forces, the fleet was able to operate with confidence without being challenged by foreign vessels. A Hainan Province Government document referred to these operations as “Spratly rights protection” by “civil forces” (民间力量), ostensibly a combination of normal fisheries production and the maintenance of an increased civilian presence.

Presence at Second Thomas Shoal

Between 27 February and 28 March 2014, command and supply vessel F8168 and seven of Fugang Fisheries’ large trawlers coordinated with Sanya City’s People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD) in the standoff with the Philippine’s makeshift outpost at Second Thomas Shoal. Although it is unclear what role the Fugang flotilla played during the Chinese interference in resupply of the grounded Philippine landing craft BRP Sierra Madre, it reportedly conducted “ceremonies to display sovereignty” with officers from the PAFD. Moreover, the trawlers’ shallow draft would have allowed them to operate in all areas accessible to Philippine resupply vessels, in contrast to larger PLAN warships or even CCG cutters that might have risked grounding. Philippine forces were only able to successfully resume resupply of their outpost the day after the militia was reportedly recalled. Assuming that Fugang’s vessels did not run out of supplies, this may have been an early indication of Chinese intention to loosen its interference. Two days later, a People’s Daily Overseas Edition articled a rationale for allowing the resupply, asserting that China had initially intended to prevent the delivery of construction materials to reinforce the deteriorating outpost. It credited Chinese restraint, clarifying that Philippine resupply vessels on 29 March 2014 carried only food, water, and journalists—not construction materials.

Picketing in Haiyang Shiyou 981 Standoff

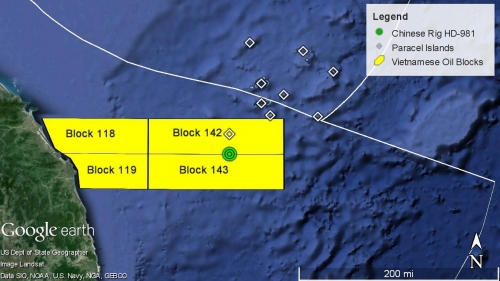

In April 2013, Hainan’s People’s Armed Police Border Defense summoned Fugang Fisheries Co. to provide escort and rights protection functions for oil exploration in the waters south of Triton Island (中建岛) in the Paracels. This area, referred to as Zhongjiannan Basin (中建南油井) by China and Nha Trang Basin by Vietnam, is plagued by disputes over energy deposits between the two countries. Escort was reported to have been conducted by Fugang Fisheries for a total of 30 days. While no specific details were released regarding the patrol, this oil exploration overwatch was likely for the wellsite investigation China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) conducted in 2013, as it later referred to the 2014 placement of the Haiyang Shiyou (HYSY) 981 drill platform in the disputed waters as “phase two” of exploration and development plans for this basin.

On 4 May 2014, Fugang Fisheries dispatched a “militia fleet” of 29 trawlers to support the Guangzhou Military Region and Hainan Military District commands in protecting HYSY 981. This occurred south of Triton Island, the same area where Fugang conducted escort functions for oil exploration operations the previous year. The involvement of military region and military district commands illustrates just how many entities were involved in protecting HYSY 981. This force is reported to have maintained its “rights protection” operation around the platform for over two months. Altogether it drove away, rammed, and obstructed more than 80 Vietnamese “armed trawlers,” which reportedly approached in more than 20 “waves.” In the process, “China’s militia trawlers rammed and destroyed three Vietnamese trawlers.” This demonstrates that Fugang Fisheries Co.’s militia was present during multiple stages of CNOOC’s activities in the Zhongjiannan Basin.

Exhibit 5: HYSY 981 oil rig’s location vis-à-vis Vietnam’s Energy Blocks. Image credit: CSIS

Command and Control

One can see the variety of command authorities China’s maritime militia work under; with the PAFD and local military commands providing overall control of the militia, but also allowing for ad hoc command arrangements such as “rights protection” missions under the CCG or FLE forces. Although Chinese militia operations to obstruct the Impeccable in 2009 were ordered by the then-head of the SCS Bureau of Fisheries Law Enforcement Wu Zhuang, as documented by Ryan Martinson, it is unclear whether this same structure continued in later missions. Wu Zhuang’s command in 2009 was likely facilitated by rapid, flexible mobilization arrangements through the unit’s PAFD in Sanya, or at least with some degree of approval from local military organs. These overall patterns are documented in numerous Chinese sources describing how China’s maritime militia is mobilized and commanded.

The Sanya PAFD reportedly keeps track of and communicates with its maritime militia through 250-Watt Single-Side-Band Radio, satellite phones, and very likely the Beidou satellite navigation message transmitting service commonly installed on maritime militia vessels. Hainan installs the Beidou system on all trawlers of 80-tons displacement and greater. Since larger tonnage trawlers provide greater operating ranges and the ability to intimidate other foreign fishing vessels, they are also the most suitable to recruit into the maritime militia. Most vessels in Sanya’s maritime militia, similar to maritime militia in other locations, would be required to have the necessary electronic communications equipment to ensure command and control during operations. Larger trawlers were employed in events such as Sanya’s expedition to the Spratlys in 2012, wherein all participating trawlers displaced 140 tons or more.

Sanya City’s 2013 Yearbook designated maritime militia and emergency response militia as foci of effort in the prior year’s militia reorganization work. In accordance with this emphasis, a maritime militia pilot program was enacted in 2012, whereby Hexi District, Tianya Township, and Yacheng Township each established its own maritime militia detachment. Hexi District’s unit, a maritime militia reconnaissance detachment, is composed of more than 100 militiamen and at least 12 vessels. Other districts have also established units, albeit smaller in size and more likely to be coastal response militia units on small craft, without the sea-going capabilities of entities like the Fugang Fisheries Co. The city government has also allocated special funds to build headquarters for the maritime militia, as well as to train and equip them with everything from navigational radar and communications gear to such basics as binoculars and life vests. No available evidence suggests that these units have been, or will be, allocated light arms. However, they are given precursory training in their use. Two short Internet videos show maritime militia receiving light arms training. One documents Sansha City’s maritime militia engaged in such training. The other shows militia from Guangxi military district’s training in the Gulf of Tonkin. Tasked with protecting China’s sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the SCS, the Sanya maritime militia has coordinated with maritime law enforcement agencies to conduct numerous patrols of the Paracels and the Gulf of Tonkin areas. Since 2012, it reportedly monitored 190 foreign fishing vessels and drove away 60 vessels that, from China’s perspective, were fishing illegally.

In March 2013, Deputy Chief of Staff of the PLA Admiral Sun Jianguo—the most likely successor to Admiral Wu Shengli as PLAN commander—inspected Sanya City’s maritime militia forces. He was then concurrently serving as secretary of the State National Defense Mobilization Committee, with responsibility for overseeing defense mobilization affairs, including militia work. It should be no coincidence that he made his inspection one month prior to the increase in Sanya’s maritime militia activities in the SCS, according to the sequence of events involving Fugang Fisheries Co.’s maritime militia listed above. Based on the typical practices of PLAN and other Chinese officials, Deputy Chief of Staff/Secretary Sun provided some “guidance” (指导), likely concerning the city’s future use of maritime militia in SCS operations.

Infrastructure Expansion

For all its contributions to date, Sanya’s maritime militia forces are sailing towards an even brighter future, propelled by political support, government investment, and infrastructure expansion. Situated on Hainan’s southern coast in a major city with sprawling naval facilities, Sanya Harbor has long been an important shelter and base of operations for China’s fishing industry, welcoming numerous fishermen and companies coming from other counties and provinces. Sanya’s prime location provides an excellent launching point for fisheries development in the SCS, attracting companies like Fujian Province-originated Fugang Fisheries to station their fleets in there. Since Hainan Province became a Special Economic Zone in 1988 and in the years of opening up that followed, Sanya City developed into a hub for tourism, shipping, and fishing. The city has grown into an international tourism center, featuring new beaches and the large man-made Phoenix Island, complete with resort hotels and a cruise ship dock. The Sanya City government wants to line its harbor with wealthy yachters and improve the city’s image as an internationally competitive vacation destination and luxury residence.

Standing in the way of this image enhancement and real estate renaissance are a thousand fishing boats of varying sizes and other merchant ships. With increasing vessels from other provinces crowding into Sanya Harbor, port congestion and pollution have become severe.

Exhibit 6: Numerous fishing vessels in Sanya Harbor

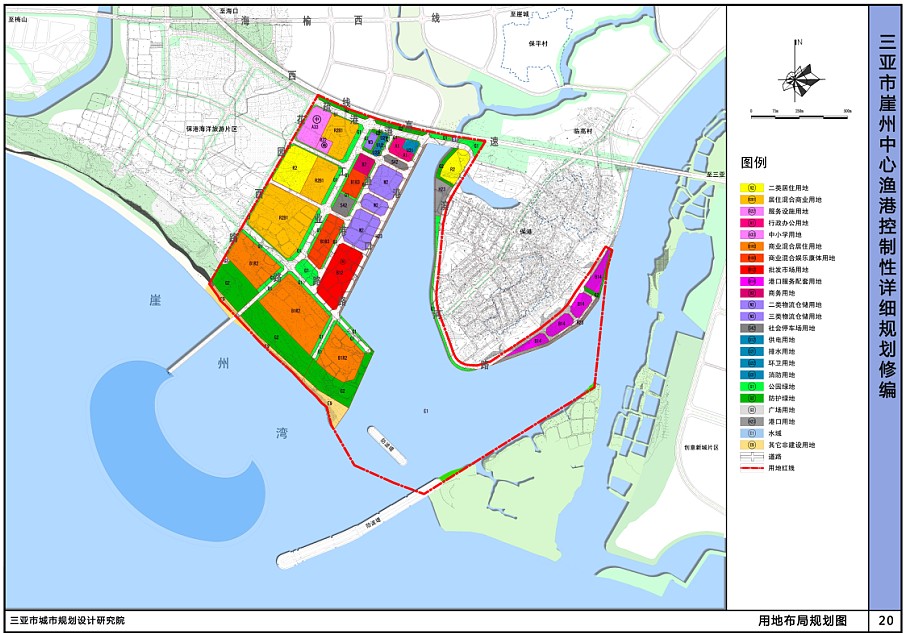

In 2005, the Sanya municipal government decided to implement a plan to divide Sanya’s marine industries into “three separate ports” (三港分离), whereby over the next decade the shipping and fishery industries would gradually shift to newly built ports west of the city proper. This plan included the construction of Phoenix Island, a shipping pier at Nanshan Harbor, and the Yazhou Fishing Port (崖州中心渔港) in Yazhou District.

Exhibit 7: City Government Plans for Yazhou Fishing Port construction, delineating functions for each portion of the shoreside

The plan is now in its final stages of implementation, with Phoenix Island and its associated facilities already complete. Yazhou Fishing Port reached initial operating capacity on 28 April 2015, although construction remains ongoing. Having advised non-Sanya registered fishing vessels to leave for Yazhou Fishing Port, the Sanya City Oceanic and Fishery Department is now scrapping obsolescent vessels left behind. Recent Google Earth imagery shows dredgers widening and deepening channels for the new Yazhou Fishing Port, affording the largest trawlers and support ships access to dockside services.

Exhibit 8: Dredgers operating alongside Gangmen Village build up Yazhou Fishing Port

The port can handle 800-1,200 trawlers, and will host manifold accommodations for the fishing fleets that will operate from it, including residential areas. Fugang’s command and supply vessel F8168 reportedly now operates from this new port. Whereas its draft was too deep to reach the fisheries dock in Sanya Harbor, it is now able to tie up at dockside thanks to the new fishing harbor’s 18-foot depth. Additionally, this new port is designed to double as a site for tourists who want to enjoy fresh seafood and immerse themselves in Hainan’s storied fishing community culture.

Exhibit 9: Command and supply vessel F8168 becomes first ship at Yazhou Fishing Port

Due to its close proximity, this new fisheries base will fall under Yacheng Village’s jurisdiction. The village’s “2011 Notice on the Launch of Militia Reorganization Work” indicated that the maritime militia constitutes a component of that district’s militia organizational planning, and contained guidance regarding maritime militia organization. The organizational practices described largely mirrored the broader methods of maritime militia organization across China more generally. With the shift of known maritime militia entities over to the newly built fishing port, this western district of Sanya City will likely become the new home base for some of Sanya’s major maritime militia units.

Maritime militia serve in a variety of locations: on fishing vessels, small craft, or merchant ships; or even in shipyards. Yazhou Fishing Port, being dedicated solely to the marine fishing industry, would likely receive most of the maritime militia based on Sanya’s marine fishing vessels. Rooted in the marine fishing industry, such forces—with Fugang Fisheries the leading example—boast the expeditionary capacity to reach more distant waters in the SCS. By contrast, some maritime militia units assigned to port security or other supporting functions—possibly for the navy or maritime law enforcement—may remain in Sanya harbor, from which they would be unlikely to venture far.

Exhibit 10: New buildings under construction to support Sanya’s fishing industry

Conclusion: Future Roles and Missions

This first article in a five-part series on the leading irregular maritime forces of Hainan Province has focused on the maritime militia of Sanya City, with Sanya Fugang Fisheries Co., Ltd. foremost among them. Examining this vanguard of vanguards has yielded insights into the status and trajectory of Chinese maritime militia development and employment. The implications for U.S. interests, presence, and influence in the SCS are significant. In the months to come, for instance, China may well dispatch maritime militia units in an attempt to make FONOPS increasingly uncomfortable for U.S. forces. Given its capabilities and experience, Fugang Fisheries may well have a significant—even a leading—front line role in such efforts.

According to Chinese military strategy, these potential harassment activities, as well as the already-documented involvement of maritime militia in such recent “rights protection” operations in the SCS as defense of the HYSY 981 oil rig, are highly logical. Yet this is just one of the functions of these versatile irregular forces. As a reserve force, the militia can be mobilized to protect the nation’s critical infrastructure—such as bridges, ports, railways, or in this case an oil drilling platform—from encroachment or sabotage. Reports of fishermen uncovering an unmanned underwater vehicle in their nets in the coastal waters off Sanya further reinforce local military and civilian leaders’ conviction that it is beneficial to strengthen the fishing population’s ability to report information, particularly the disciplined, increasingly-specialized maritime militia. PRC coastal militia and fishermen traditionally have been an important force in preventing Nationalist spies from intruding into the mainland, a role not forgotten by today’s coastal provinces.

Future contingencies will likely include more than just the maritime militia. In May 2014, Vietnam experienced first-hand the bulwark of Chinese maritime forces when a portion of its claimed EEZ was closed off for over two months by a mix of Chinese naval, coast guard, and maritime militia units protecting HYSY 981. Maritime militia called up to serve in confrontations with foreign vessels will certainly be accompanied by naval or maritime law enforcement vessels, whether they too are engaged directly, or remain in an overwatch position nearby.

With its strategically-important Yulin Naval Base and burgeoning maritime militia force, Sanya City is uniquely positioned to influence events in the SCS. As friction between regional and global powers heats up the waters around the Spratlys, the Sanya maritime militia will surely make further appearances at a time and place of China’s choosing. Potential targets of its surveillance and harassment—notably including U.S. and allied naval vessels pursuing FONOPS—must be vigilant lest they be outmaneuvered by these irregular maritime forces, China’s daring vanguard at sea.

The next article in our series on the major maritime militias of Hainan province will survey the Danzhou Militia of Baimajing Harbor on Hainan’s west coast. In January 1974, this militia played a significant role in China’s operation to seize the Crescent Group of islands from Vietnam in the Battle of the Paracel Islands. Studying the Danzhou Militia thus offers insights into one of the least understood aspects of China’s maritime militia–its potential utilization in actual warfare.

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is an Associate Professor in, and a core founding member of, the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. He serves on the Naval War College Review’s Editorial Board. He is an Associate in Research at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and an expert contributor to the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time Report. In 2013, while deployed in the Pacific as a Regional Security Education Program scholar aboard USS Nimitz, he delivered twenty-five hours of presentations. Erickson is the author of Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development (Jamestown Foundation, 2013). He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. Erickson blogs at www.andrewerickson.com and www.chinasignpost.com. The views expressed here are Erickson’s alone and do not represent the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

Conor Kennedy is a research assistant in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. He received his MA at the Johns Hopkins University – Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies.