By Corey Grey

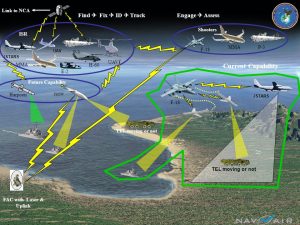

When the USS Carney (DDG-64) downed the opening salvos of Houthi land-attack cruise missiles and drones over the Red Sea in October, the Pentagon hailed the feat as a “demonstration of the integrated air and missile defense architecture.” It was much more than that. Long before Carney’s medium-range Standard Missile-2s (SM-2s) erupted from their launch cells, Information Warfare (IW) capabilities provided crucial combat support to neutralize the inbound threats, enabling these shots with critical IW equipment, intelligence, internal communications, and electronic support. In short, naval IW—with the exception of launching the SM-2s— ensured critical strategic objectives. This event, and many others like it, demonstrates the underappreciated depth of IW for the current and future fight.

As the military grapples with recruiting shortfalls, the IW community has a compelling story to counter: integrated warfighting. This narrative, epitomized by Carney and other units’ recent successes, covers efforts across a diverse range of specialties that are too often seen in isolation: meteorology/oceanography, cryptology, intelligence, communications, space, and cyber operations. As important as the success of these individual elements are for the U.S. Navy, the real impact relies on the full integration of information forces and capabilities through improved recruiting, training and career paths integration, as underscored by the recent Department of Defense Strategy for Operations in the Information Environment (SOIE).

With this in mind, the U.S. Navy should take concrete steps to further promote an integrated warfighting ethos which better incorporates all elements of the IW community, starting from initial officer training to senior level carrier strike group operations. By defining what it means to be an integrated information warfighter rather than just being an Intelligence Specialist, Cryptologist, Meteorologist, or Information Professional, the IW community will better educate, train, and most importantly, recruit the next generation of IW personnel. Equally important is the need to enhance retention. To further maintain the impressive cadre of IW personnel in service, the Navy should improve its career opportunities with better advanced training and cross-detailing availability. In the aftermath of these changes, IW will be better positioned to dominate the information environment and enable mission success.

Shared Identity

The Navy’s IW community currently boasts favorable recruiting but should do more to meet the growing demand from supported operational forces. Vice Admiral Kelly Aeschbach, Naval Information Forces commander, recently confessed that “our biggest challenge right now is facing demand. We are needed everywhere, and I cannot produce enough information warfare capacity and capability to disrupt it everywhere that we would like to have it, and so that remains a real pressing challenge for me: how we prioritize where we put our talent and ensure that we have it in the most impactful place.”

Better recruiting starts with stronger, more compelling messaging. Aviators join to fly, submariners join to drive boats, surface warfare officers to drive ships, but there is less consistency in why each IW officer volunteers for service. Future IW candidates require a holistic message that knits together the disparate range of specialties that encompass the community.

The Navy’s maritime sister service provides a clear model for messaging, encapsulated in five simple words: Every Marine is a Rifleman. This iconic phrase is based on the foundational infantry skills every Marine receives, regardless of their specialty, and the expectation that every Marine can serve in the capacity of a rifleman if called upon to do so. This narrative and ethos is so effective that last year, without any substantial increase in compensation or incentives, the Marine Corps exceeded its recruitment goals while the other services experienced shortfalls not seen in decades. Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Smith said it best: “Your bonus is that you get to call yourself a Marine.”

Sadly, the IW community lacks the clarity of the Marine Corps model. Instead, the community prescribes to an identity built around specialization. Personnel share the title of Information Warfighter, which encompasses seven officer designators and eight enlisted ratings, but the same personnel are only expected to master their own specific capability. Case in point, Congress recently compelled the Navy to produce a new maritime cyber warfare officer designator and cyber warfare technician rating due to a lack of specialization by Cryptologic Warfare Officers and Cryptologic Technicians. This change stands as criticism to the IW community as a whole as it raises questions towards their unified identity. Cyber operations cannot exist without Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) yet the Navy decided to separate the integrated IW capacity under two officer designators (1810, for SIGINT, and 1880, for Cyber Operations). Officers who joined the Navy to perform cyberspace and SIGINT functions should not have to laterally transfer to a new community to ensure they can continue to deliver and lead cyber operations. The capriciousness of this shift only leads to frustration and difficulties in recruiting and retaining talent.

Overall, the true lesson from all this is not the need to create more IW communities, but instead the need to produce a capable warfighter that can understand and provide full IW effects to the operational commander regardless of designator. Many will look to the Information Warfare Commander (IWC) position, both afloat and at maritime operation centers ashore, as the model for this vision, but how does the U.S. Navy assure future and present IW professionals that they will be properly trained to support or even become this commander?

Solutions for Integration

Although the Information Warfare Commander (IWC) for amphibious readiness groups and carrier strike groups drives the Navy towards a more integrated IW force, there is no consolidated career pipeline to properly prepare a rising officer to leverage all IW capabilities. Moreover, if that commander has done well to master his or her specialty, it comes at the opportunity cost of lesser competence in commanding an integrated force. More training is needed to ensure junior IW professionals feel competent, confident, and motivated to stay in the Navy through this milestone. Lengthening and strengthening courses that all IW officers can attend, such as the Information Warfare Officer Basic Course and Information Warfare Officer Intermediate Course, would better develop and refine how every IW specialty supports the fight while also fostering an integrated warfighting ethos, starting from the officer corps and spreading to the enlisted ratings. These trainings should highlight integrated IW operations for air, surface, sub-surface, naval special warfare, amphibious readiness group, and carrier strike group operations while leveraging evolving initiatives such as live, virtual, and constructive training. IW leaders would then be well postured to motivate and further develop the diverse cadres within the larger community.

Beyond better messaging and training is the need for increased cross-detailing, that is, assigning an officer from one IW discipline into a billet normally filled by another. The aim of this process is to ensure greater exposure and integration as IW officers broaden their experiences serving in capacities that are not traditionally aligned with their core skills. However, the IW force is not fully exposed or integrated because few leadership positions at the O-4 to O-6 levels are available for cross-detailing. These few billets are highly selective; consequently, most IW officers will never work outside their designator. The largest pool of IW officers, namely junior officers, are thus unaware of the full breadth and scope of the IW community due to a lack of experience and exposure. One especially important key to retaining talented people is to provide broader career opportunities, especially when they are most impressionable and likely to decide whether to stay in the Navy or leave for industry.

In a time when IW officers are filling senior roles once thought exclusive to unrestricted line officers, such as chief of staff, maritime operations center directors, and IWC, the question stands how they have not fully integrated within their own community. It is inconsistent to think that an Intelligence Officer can serve as the Commanding Officer of the largest Navy Information Operations Command (traditionally a Cryptologic Warfare Command) but a cryptologist cannot serve as a numbered fleet N2/N39. The same can be said for a number of other IW billets at every level. Certainly there are some positions that are best served by specific designators but this should be the exception and not the rule. The lack of cross-detailing creates identity challenges that degrade both community effectiveness and retention.

More deliberate solutions for integration, such as consolidating new accession IW officers under one broad designator and then having them select specific community tracks later in their careers, similar to the Navy’s Human Resource Officer community, should also be considered. Officer candidates would be presented with the full IW portfolio and then have the opportunity to select and support any of the various disciplines. After a set number of years being exposed to the broader community, the officer would then select a designator track from one of the IW disciplines. This could be implemented via a competency based selection process as determined from additional qualification designations (AQDs), type of assignments completed, and personal preference. The framework would enable deliberate career development, preparing officers to better succeed in more challenging IW assignments while also offering greater exposure and integration to succeed in senior level Information Warfare Commander positions.

Five Simple Words

With these solutions and more in this vein, operational commanders will be able to look to a fully pinned IW professional and receive an authoritative voice in navigating throughout the entire IW domain. This expectation should not be reserved for the select few who serve as IWC but for each individual who belongs to the IW community. IW is a compilation of many specialties in one vast domain and each sailor must be able to understand their place within it. As each member of a ship’s crew understands his or her place in maintaining a warship afloat, so must all IW professionals as they sail through the information environment.

The generalist versus specialist argument is not novel, yet these assertions go beyond that. The Navy must refit the individual IW operator’s identity towards integrated domain operations. Attracting and retaining qualified talent to meet the heavy IW demand necessitates a full commitment towards greater interconnectedness. Fourteen years have passed since the establishment of the IW community and while progress has been made, great strides still need to be achieved towards full synthesis. Without a comprehensive approach that meaningfully gets to how the IW community better integrates – from messaging, to training, to detailing. It is questionable whether the Navy will indeed be capable of recruiting and retaining forces for the many and varied challenges along the horizon. More must be done and a good place to start is by putting the community’s initiatives and visions into five simple words – “Information Warfare is Integrated Warfare.”

Lieutenant Corey Grey is a cryptologic warfare officer, qualified in information warfare and submarines. He holds a master’s degree from the Naval War College in defense and strategic studies with an Asia-Pacific concentration. He is assigned as the cryptologic resource coordinator on the staff of Commander, Submarine Group Seven.

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (Aug. 25, 2023) Operations Specialist 2nd Class Itzel Ramirez identifies surface contacts in the combat information center of the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Paul Hamilton (DDG 60) in the Pacific Ocean, Aug. 25, 2023. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Elliot Schaudt)