By Lieutenant Commander (G) Roshan Kulatunga, Sri Lankan Navy

Introduction

The geostrategic and geopolitical importance of the Indian Ocean Region has been understood by many great maritime historians. During the Cold War the United States was the preeminent maritime power and the USSR the preeminent land power. Lack of maritime capability eventually became a losing point for the USSR where the U.S. dominated the global commons. Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan stated the importance of sea power by highlighting six elements of geography (access to sea routes), physical conformation (ports), extent of territory, population, character of the people, and character of government. Mahan’s maritime concepts were so influential in the field of maritime studies that most of the contemporary maritime security architectures are designed around these concepts.

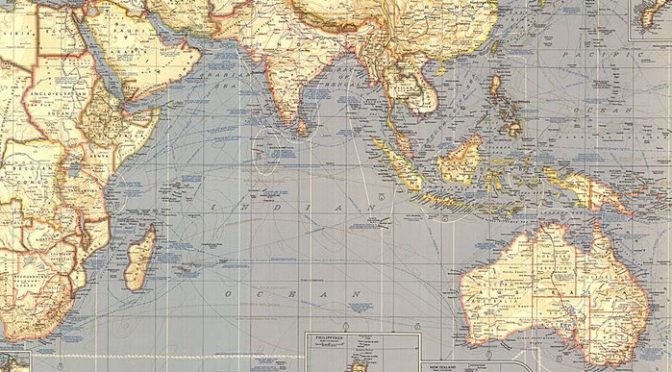

The 21st century Indian Ocean receives attention from state and non-state actors. According to Robert Kaplan “The Indian Ocean unified the oceans and it connects the world from Africa to far East.” Mariners use sea lanes for transportation, and today the Indian Ocean holds some of the most important sea lines of communication in the world. There are regional and extra-regional states operating in the IO. Extra regional countries such as the U.S., China, Japan, and Russia are keen to have some presence in the IO. They are interested in projecting sea power beyond their locale to garner economic and political sustainability in the world arena, and where the IO is a major arena of competition.

The Concept of Sea Power

Establishing preeminent sea power is a key geopolitical strategy successfully implemented by great maritime empires such as England. The famous professor for international relations, Barry Buzan, names five sectors of security that are namely military, political, economic, societal, and environmental. Maritime security lies over all these five sectors of security. Maritime historians such as Admiral Mahan, Julian Corbett, and modern maritime experts such as Robert Kaplan and U.S. Navy Admiral Michael Mullen are well-recognized persons who often talk about the value of maritime power. Admiral Mullen points out that “Where the old maritime strategy focused on sea control, the new one must recognize that the economic tide of all nations rises not when the sea are controlled by one, but rather when they are made safe and free for all.”

Sea power is a larger concept than the field of maritime warfare. Humanity uses the sea for many reasons and these reasons are well-connected to each other. As historian Geoff Till puts it, the “Sea can be used as a resource, medium of transportation, medium of information and medium of dominion.” In history great civilizations founded primarily on maritime power were termed “thalassocracies,” which literally translates to “sea power.” Establishing sea power is directly helpful to strengthening a variety of national policies as it is the collective effect of the military and civil maritime capabilities of a country. Therefore, regional and extra-regional users in the IO are interested in projecting their sea power via both civil and military maritime capabilities.

Geostrategic and Geopolitical Significance of the Indian Ocean

Geopolitics has been defined as a struggle for power and national power can be evaluated in part by showing the interrelationships between geostrategic positioning, the relative economic and technological capabilities of states, international public opinion, international law and morality, international government and diplomacy, and the regional and global balance of power. Geo-strategy is required to deal with geopolitical problems and is the sum of the efforts to influence and act through these factors. With developing economies and growing energy requirements, users in the IO are struggling for power and this behavior influences the stability of the IO.

This is the container age of maritime trade. Bulk cargos are transported through chokepoints in the IO and through main ports such as Gawdar, Chabahar, Hambanthota, Colombo, Mumbai, and Chittagong. These major ports have given significance to IO nations and made them maritime influencers in their own right. There are also nearby flashpoints that can cause spillover effects in the IO with existing situations in Yemen, Somalia, and Iran. Therefore, security in this region is very important for the global economy and must be secured from Middle East turbulence. The countries in the IO are mostly in the developing stage and handling the third largest ocean in the world becomes a huge challenge for them. Therefore, extra-regional countries pay close attention to this region in an effort to influence stability.

Extra-Regional Powers in the Indian Ocean Region

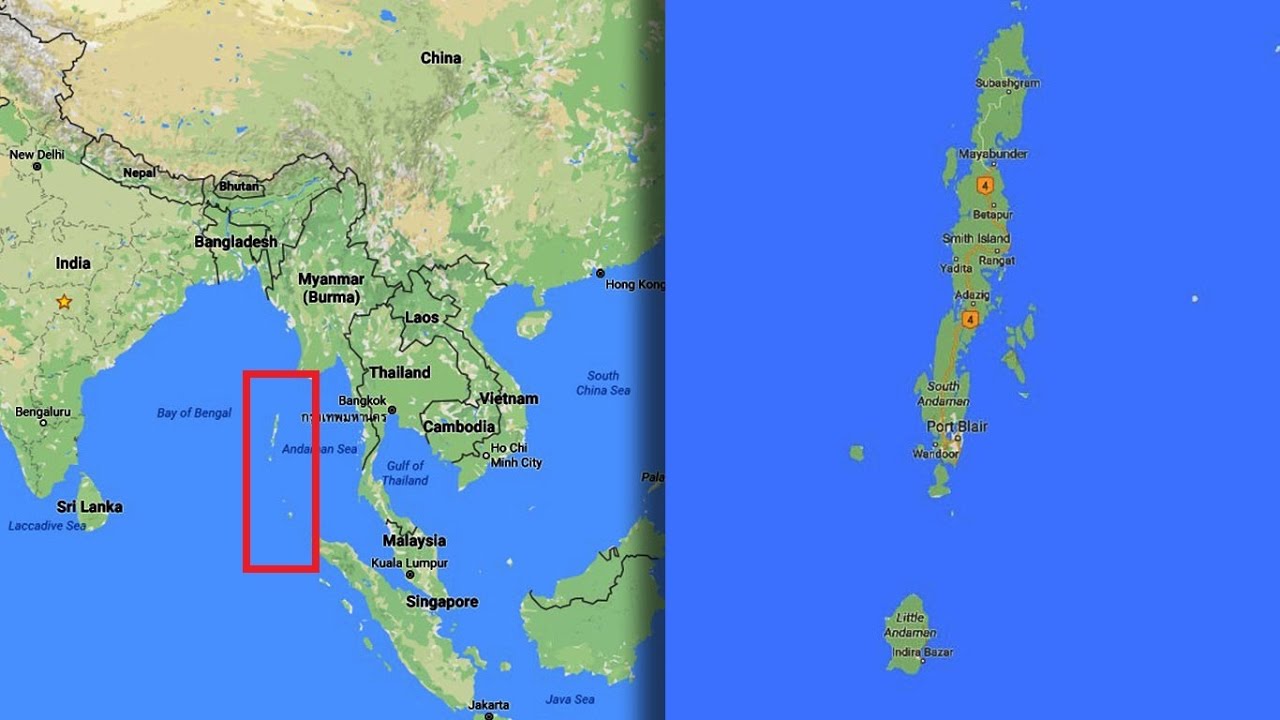

There are 35 Littoral States and 12 landlocked countries, and altogether 47 counties in the Indian Ocean Rim (RIM). Apart from that, many extra regional countries such as China, U.S., Japan, and Russia are dependent on the IO and working to expand their influence. China is interested in the Maritime Silk Route (MSR), and according to Kaplan, China is expanding vertically while India expands horizontally in their maritime power projection. The U.S. sphere of interest is spreading from the Western Pacific to greater maritime Asia in the 21st century, and recently renamed its Pacific Command to Indo-Pacific Command in recognition of the growing importance of the IO. However, there are not any notable maritime power rivalries from within IO nations themselves. Countries are well aware of security in chokepoints, sea lanes, and strategic waterways. Trade security is the major substantial security factor in their developing economies. Therefore, countries are reluctant to disturb in good order at sea.

India, the U.S., and China are main power blocks in IO and they are with the intention of extending their maritime power in pursuit of their national interest. When looking into the balance of power in IO, China seeks maritime expansionism through the South China Sea to IO. The U.S. is more allied with India in present day context than earlier times. Presidents Barack Obama in the past and Trump at present have had good maritime diplomacy with India. According to Morgenthau alliances are a necessary function of the balance of power, when nations competing with each other have three choices in order to maintain and improve their relative power positions. They can increase their own power, they can add to their own power through the power of other nations, or they can withhold the power of the other partner nations of the adversary. Small states like Sri Lanka, Maldives, and Seychelles have to be considerate of their alliances with great powers as they are players in a larger competition.

When linking this setup into the IO, China and the U.S. are competing with each other and India is also competing with China. China has its own issues with the South China Sea and the security dilemma in Malacca Strait especially affects her. Therefore, aligning with Myanmar and Bangladesh is important to China to transport energy if any rivalry worsens. Further, they have notable interests in the ports of Habmanthota, Gwadar, and Chabahar. The U.S. on the other hand has common interests with India. India has its own maritime strategy involving relationships with the smaller states like Sri Lanka and the Maldives. The recent past visit of two Chinese submarines to port Colombo was heavily criticized by Indians as a challenge to maritime security. The evolving nature of IO alliances could be further strengthened by the construction of oil pipelines for refueling and oil transportation in deep sea ports by India and China in Chabahar in Iran and Gawadr in Pakistan, respectively.

The Chabahar and Gwadar ports are strategically important to both India and China for their maritime expansion. India along with Japan introduced the Growth Corridor, which links Africa to Asia and Far East. Sri Lanka, for example, is situated along both the SLOCs for the Growth Corridor and One Belt One Road. Therefore, smaller littoral state like Sri Lanka have to open up trade to many parties to receive the benefits from competing trade routes and economic projects.

Maritime Security Threats and Challenges in the Indian Ocean Region

Threats and challenges to the IO maritime domain can be divided into two major areas of traditional and non-traditional security threats. Both littoral and extra-regional states have to play a vital role to prevent the maritime domain from threats and challenges.

Interstate conflicts are rarely found in this region. With the economic expansionism, countries cannot neglect the threats of piracy, illegal fishing, maritime terrorism, maritime pollution, irregular migration by sea, illegal narcotic drugs, and small arms trafficking by sea. These threats may have traditional implications for extra-regional maritime users. As an example, small numbers of Somalian pirates are able to create a perception of threat to the entire maritime trade in the IO. Countries had to utilize their resources to counter this threat in a sustained and multilateral fashion. They had to have interdependencies to face this issue without considering individual rivalries.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is another important issue. IUU fishing can also add economic power to actors that also perpetuate maritime terrorism, human trafficking, and illegal migration at sea. Countries like Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Myanmar are highly notable victim countries for human smuggling. Sri Lanka is considered a major source country on this issue. Suitable Maritime Domain Awareness mechanisms would be the possible solution to mitigate these threats in the IO. Diplomatic and multilateral solutions are the most viable action on this issue and again counties have to use conference diplomacy to peacefully engage in these types of challenges.

Conclusion

The IO is the third largest ocean in the world and for the balance of power extra-regional actors always wish to display their presence in this region. Therefore, geo-strategic and geo-political competitions in this region are inevitable. Regional and extra regional countries are much more concerned with China’s maritime expansionism in particular. China is especially interested in becoming a modern maritime civilization. This is evidenced by its constructions of harbors in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Myanmar. This has generated vulnerability to their balance of power and traditional regional relationships. Due to the economic advantages they littoral are reluctant to create any rivalries. However, their own game of survival is inevitable.

Security is an important factor for a nation state. To be survivable in the international arena nation states have to concern themselves with energy and trade security. Therefore, the nation state has to give much more concern for their maritime security in a world whose globalization is being fed by the world’s oceans. IO strategic waterways have taken special attention in maritime trade. Oil trade is flowing from the Middle East to Asia and elsewhere via these IO chokepoints and sea routes. Their protection is the responsibility of all.

Lieutenant Commander Roshan Kulatunga is presently performing duties in the Sri Lanka Navy. He is a specialist in Gunnery, from INS Droanacharya, India. He earned a Diploma in Diplomacy and World Affairs at Bandaranaike International Diplomatic Training Institute, Sri Lanka. He also holds a degree in BNS (Bachelor in Naval Studies) University of Kalaniya Sri Lanka, MSc in Security & Strategic Studies, MSc in Defence and Strategic Studies in Kotelawala Defence University (KDU), Sri Lanka. His research interest includes, Maritime Domain Awareness in the Indian Ocean Region

Bibliography

Colombage, A. J., 2017. Maritime Security in the Indian Ocean: Contest for power by major maritime users and non-traditional security threats. Defence and Security Journal, 1(1), p. 103.

Department of the USA Navy, 2009. Maritime Domain Awareness in the Department of the Navy. Washington: Secretary of the Navy.

Ghosh, C. P. K., 2004. American-Pacific Sealanes Security Institute conference on Maritime Security in Asia. Maritime Security Challenges in South Asia and the Indian Ocean: Response Strategies.

Gunawardena, C., 2015. Sri Lanka Navy Outlines Importance of Maritime Hub in Seminar Sessions.

Jayawardena, A., 2009. Terrorism at Sea. Maritime Security Challenges in South Asia.

Kaplan, R., 2011. Monsoon. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks.

Kaplan, R., 2013. The Revenge of Geography. New York: Random House Trad Paperbacks.

Mihalka, M., 2005. Cooperative Security. Cooperative Security in the 21st Century, Volume 3, p. 113.

Morgenthau, H. J., 2005. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

NMDAP, 2013. National Maritime Domain Awareness Plan. New York: Presidential Policy Directives.

Rabasa, A. & Chalk, P., 2012. Non-Traditional Threats and Maritime Domain Awareness in the Tri-Border Area of South East Asia. p. 21.

Sheehan, M., 2006. International Security, An Analytical Survey. New Delhi: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc.

The Indian Ocean and the future of American Power. 2010. [Film] s.l.: s.n.

Thean, P. T., 2012. Institute for Security Studies Paper. Maritime security in the Indian Ocean: strategic setting and features, Issue No – 236, p. p.4.

Thiele, R. D., 2012. Building Maritime Security Situational Awareness, Issue No – 182.

Till, G., 2013. Sea Power, A Guide for the Twenty First Century. New York: Routledge.

Featured Image: North and South Malosmadulu Atolls in the Maldives. Image taken by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) onboard NASA’s Terra satellite. Source: ASTER gallery. Courtesy of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/Japan Space Systems and the U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team.