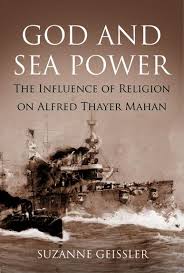

God and Seapower: The Influence of Religion on Alfred Thayer Mahan by Suzanne Geissler. USNI Press, October 15, 2015. 280pp. $39.95.

For many of us, Alfred Thayer Mahan is certainly no stranger. His theories and writings have been talked about and analyzed for years. They have been savored by everyone from the President of the United States, the lowly Naval War College graduate, and many others around the world. Thus, it is always refreshing to read something new and interesting about this well-known and often talked about historical figure. Suzanne Geissler has done just that. Professor Geissler has delivered some fresh insights and probably stirred some debate with her new book, God and Seapower. The book is a fascinating look into Mahan’s life by focusing on his religious beliefs. At 280 pages this book is a nice size; something that can be read in a week and yet she still manages to cover ATM’s life, from childhood to wise naval theorist, quite nicely. Recently I had the opportunity to interview Professor Geissler about her new book. What follows is the transcript of our interview which was conducted over e-mail.

Why Mahan and Religion? Why did you want to write this book?

My specialty is American religious history, but I have always been interested in military and naval history, more as a hobby than a professional specialization. Many years ago – I don’t remember why or in what context – I read that Mahan was an Episcopalian. I’m an Episcopalian, too, so I just filed that away as an interesting factoid, but didn’t think much more about it. Then some years later I read Robert Seager II’s biography of Mahan and came away disappointed in the book, but intrigued further about Mahan’s religious involvement. I did a little digging and discovered that he wrote extensively about religion and church issues. There was tons of stuff out there that no one had ever looked at in a serious way. I thought there had to be a significant story here.

The book, in part, is a counter argument to one of Mahan’s most well-known biographers, Robert Seager II. Readers will quickly realize that you disagree with many of Seager’s opinions. Who was Seager and why do you disagree with him so strongly?

Seager was a former merchant mariner who had become an academic historian. A few years prior to his biography coming out he, along with Doris Maguire, had co-edited Mahan’s papers. He used that as the raw material for his biography of him. The problem with the book, as I think is readily apparent after only reading a few pages, is that Seager thoroughly disliked Mahan. Now I’m not saying that a biographer has to like his subject, but there needs to be at least an attempt to be fair and look at the sources in an impartial manner. But Seager so disliked Mahan – as though he knew him personally and couldn’t stand the guy – that it colored the entire book. Everything Mahan did throughout his whole life, from the trivial to the monumental, is presented in the worst possible light. Also, the whole book is written in a sarcastic tone – what today we would call snarky – that becomes really tiresome after a while. My biggest beef with Seager is that he loathes – and I don’t think that’s too strong a word – Mahan’s religious devotion and piety and thinks it is the root of all that makes Mahan so – and these are Seager’s words – arrogant, egotistical, racist, to name a few. Seager is entitled to his own opinion, of course, but the more I got into the sources, Mahan’s own letters and writings, the more I saw that Seager had no interest in being fair or even attempting to understand Mahan in the context of his own time. My other complaint about Seager is that on numerous occasions he either disregarded what a source clearly said or twisted it out of context in order to present Mahan in a bad light.

On what points do you agree with Seager on Mahan?

The only thing I agree with Seager on is his statement that Mahan wrote the most influential book by an American in the nineteenth century.

You mention Mahan’s father and uncle were two of the biggest religious influences in his life. How so?

Mahan’s father, Dennis Hart Mahan, was a former Army officer and professor of engineering at West Point for almost fifty years. He was a monumental figure at West Point and in the Army officer corps. In those days the field of military engineering included strategy, tactics, and military history. So Alfred had a role model of exceptional brilliance whom Army officers – including people such as Grant and Sherman – held in awe. Alfred got his introduction to military history through his father. But Dennis was also a devout Christian and Episcopalian who modeled those attributes to his son. Dennis epitomized the 19th– century ideal of a “Christian gentleman” but in a way that was genuine, not superficial. Milo Mahan, Dennis’s younger half-brother, was an Episcopal priest and professor of church history at General Theological Seminary, the Episcopal seminary in New York City. Alfred lived with him for two years (when Alfred was fourteen – fifteen and attending Columbia University), a period which imbued him with Milo’s High Church piety. For the next fourteen years or so, Milo was Alfred’s main theological mentor. They had an extensive correspondence and Milo provided Alfred with reading lists of theological works which Alfred read on long sea voyages. As Alfred told his fiancée, Milo was the man he went to with any biblical or theological questions. All that reading, under Milo’s guidance, in effect gave Alfred the equivalent of a seminary education.

Mahan’s father, I didn’t realize, was well-known in political and military circles in the 19th century. When did Mahan step out of his father’s shadow?

One of my favorite anecdotes occurs in the waning days of the Civil War. Alfred is on Admiral Dahlgren’s staff stationed off Savannah when the victorious General William Tecumseh Sherman arrives in the city. Alfred goes ashore to see Sherman bearing a congratulatory telegram from his father. Sherman greets him by saying “What, the son of old Dennis?” Certainly, for more than half of his active duty career Alfred was best known for being Dennis’s son. He doesn’t really emerge from his father’s shadow until the publication of his first book The Gulf and Inland Waters in 1883 when he’s forty-three. This book leads to his appointment at the Naval War College which in turn leads to the publication of his lectures as The Influence of Sea Power Upon History.

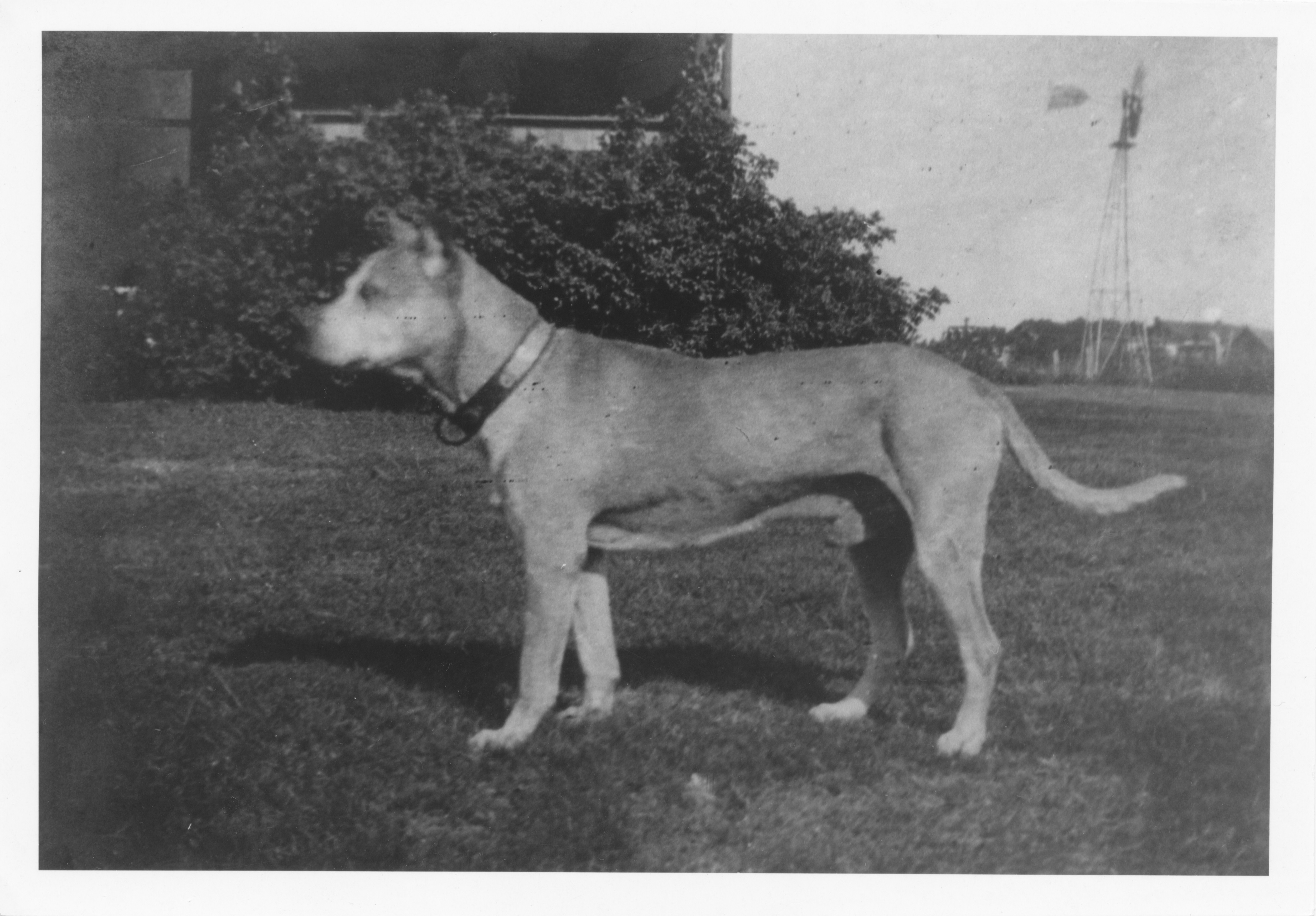

Mahan loved his dog, Jomini. And as you quote, Mahan believed his dog would go to heaven when he died. Was this belief, that a dog’s soul goes to heaven, abnormal for an Episcopalian at this time?

Mahan never expounds on the reasons that he believes his dogs, Jomini and Rovie, went to heaven, so I have to extrapolate based on what I know about this issue and Mahan’s own beliefs.

As I understand it, the Roman Catholic Church teaches that animals don’t go to heaven because they don’t have souls. Most Protestants, though, considered the “soul” issue irrelevant and based their view – that we will see our beloved pets in heaven – on the fact that animals clearly are part of creation and God has promised that all creation will be redeemed (Romans 8:21). Mahan knew his Bible thoroughly so I’m willing to bet that he would have based his view on this scripture rather than abstract speculation on whether animals have souls or not.

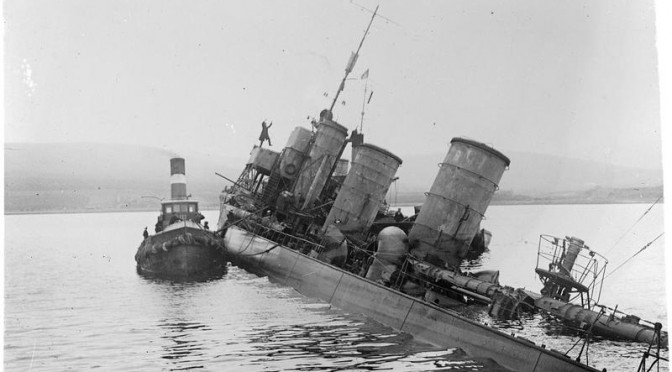

One of your more, shall we say, contentious statements, is that Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History was inspired by God. Could you expand on this?

Well, I don’t claim that, but Mahan certainly did. In his autobiography, From Sail to Steam, he made reference to his “special call” to be a naval historian, or, more specifically, to be the expositor of the importance of sea power on the course of history. He never claimed that he discovered the concept. He was always generous in crediting previous historians whose thought influenced his. But he claimed that “in the fullness of time” – a biblical expression — the call was given to him to be the one who explained it and drew the correct implications from it.

What did Mahan think of Catholics? Other Christians? Other religions?

I’m simplifying a lot here, but, basically, Mahan had a kind of layered view of religious categories. Christianity was better than other, i.e. non-Christian, religions (though Judaism was in a special category as Christianity’s older brother, so to speak). Within Christianity, Protestantism was best, and within Protestantism, Anglicanism was best. Having said that, I should point out that the groupings within Christianity related mainly to polity (types of church governance), liturgy (forms of worship), and history. Mahan clearly had his preferences, but he never claimed that, for example, there was only one true church. For him the most important thing was to be a Christian. If you loved Jesus and accepted him as Lord and Savior, it did not matter what denomination you belonged to. In a similar vein, Mahan once stated that he would cooperate with any Christian group in evangelistic or missions work as long as such a group did not include Unitarians. He did not consider them Christians since they did not recognize the divinity of Jesus. One of the things that makes Mahan so fascinating to me is that he’s not easily pigeon-holed into conventional religious categories. On the one hand he’s very much a High Church Episcopalian, but he’s also very much a born-again evangelical.

Was Mahan able to separate his writing? That is, did he keep naval theory separate from his religious writing? It seems like he was able to live in two different worlds on the page, yet his religious life infused everything he did.

Mahan was actually quite sophisticated in his historical methodology. He understood that history and theology were two different fields, each with its own ways of interpreting events. As a Christian he believed that God was the sovereign creator and ruler of the universe and God’s decrees always came to pass. However, he understood that God operated through what theologians called “secondary causes,” that is the choices made by human beings and their resultant actions. A historian deals with secondary causes. It was extremely rare for Mahan to speculate on God’s purposes in his naval history writings.

For those readers that wish to read a book on Mahan after they read your book, what do you recommend?

I recommend Jon T. Sumida’s Inventing Grand Strategy and Teaching Command: The Classic Works of Alfred Thayer Mahan Reconsidered. This is a fascinating book full of original insights on Mahan.

Are there other historians working today that do not have a theology background, yet pay serious consideration to their subject’s religious belief? Specifically, military biographies?

This is difficult for me to answer since I don’t really know who is working on what topics, especially in military biography. But the two naval historians who were most helpful and encouraging to me when I undertook this project, Jon Sumida and John Hattendorf, are both very interested in religion and the role it plays in people’s lives. And they both have a positive view of it rather than a negative one. Hattendorf, particularly, is very knowledgeable about the Episcopal Church. In his editing of the writings of Admiral Stephen B. Luce he does incorporate a discussion of Luce’s piety.

Why do you think religion so often takes a back seat when we discuss historical figures — past or present? Or does it?

As I mentioned, my field is religious history, so for most of the people I read and study about, by definition, religion is important. However, you’re right, in other historical sub-fields religion is usually ignored or misunderstood. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr. comes to mind. Even in a case such as that, where you would think the religious angle would be obvious – his being a clergyman and pastor — there are some writers who have downplayed that and made his story one of “social justice” and politics, completely ignoring the biblical roots of his thought, not to mention his dramatic conversion experience. I don’t like to generalize about historians, but in order to answer your question, I’ll do it anyway! Most present day historians are either indifferent or hostile to religion, especially the notion of an individual having a personal encounter with God, or believing that God has called that person to a specific task in life. Some writers see this sort of thing as just an eccentricity, not necessarily bad, but of no real significance. Others take a more negative view and see religious faith as a personality defect that could have pernicious consequences. One thinks of all the historians who have blamed the defects of the Versailles Treaty on Woodrow Wilson’s Presbyterian piety.

Suzanne Geissler received her Ph.D. in history from Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. She also holds a Master of Theological Studies degree in church history from Drew University. She is professor of history at William Paterson University in Wayne, NJ. Her previous books include Jonathan Edwards to Aaron Burr Jr., Lutheranism and Anglicanism in Colonial New Jersey, and “A Widening Sphere of Usefulness”: Newark Academy 1774-1993.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson is a US naval intelligence officer and recent graduate of the US Naval War College and the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island. The opinions above do not necessarily reflect those of the US Department of Defense or the US Navy.