By Christopher Nelson

A little over a month ago, I had the opportunity to sit down and talk to Rear Admiral James Goldrick, RAN(ret.), over lunch. It was a fascinating conversation that covered books, naval history, and yes, even coal. Admiral Goldrick is, in my opinion, that rare naval officer that combines a deep understanding of history with operational naval experience. I hope you all enjoy the interview as much as I enjoyed talking with him.

Admiral, thank you for taking the time to sit down and talk. Starting off, who is a historian writing today that you admire? And why?

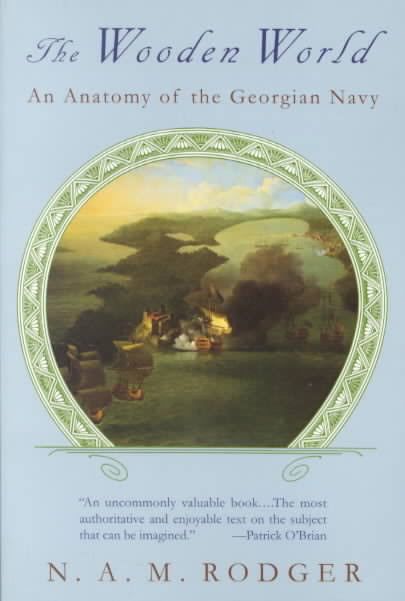

Nicholas Rodger. Nicholas – apart from an extraordinary intellect, the ability to read in multiple languages, a wonderful literary style and a very strong work ethic – has the ability to look deeply, to look again, and to bring things together. All that is combined with a deep understanding of how navies work. He is currently writing a three volume history of the British Royal Navy. The first two volumes (The Safeguard of the Sea and The Command of the Ocean) have already been published, and he is currently working on the third. Now, it’s not in fact a history of the British Navy – it is a naval history of Britain. I particularly admire Nicholas because he avoids the trap that naval historians often fall into, that is, of being too tunneled. What he is trying to do is explain the role of the navy as a national institution and what its relationship was with the nation. What is quite clear from his studies, for example, is that it can be strongly argued that the Royal Navy was a key trigger of the industrial revolution. The things required for the Royal Navy – for example, long range distribution and preservation of food – helped with the ability to operate big industrial cities. The mass production systems developed to run Nelson’s fleet – the manufacturing of blocks, and so on – were another contribution through the application of such ideas in the commercial sphere. Like all the greatest historians, Nicholas can synthesize a great deal of information and bring it all together to tell a story. What I can tell you, is that his third volume is late. And the reason for that is that, while he always knew that he had to synthesize a massive amount of material for the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, he has also found that the canon of naval history in the modern era is superficial. When you start to dig into things, you often realize that is not the way it works, that is not the way it happened.

Talking earlier, you mentioned Rodger’s book The Wooden World, and strongly recommended it, and that the movie “Master and Commander” was in part based on that book, which is something I had not heard before.

One of the reasons I think it is really important, and a  really good book for naval officers to read, is because Master and Commander is slightly anachronistic. What Nicholas is talking about in The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy is the mid-18th century Royal Navy, although Peter Weir and Russell Crane applied it to the service of the Napoleonic Wars as, arguably, did the author of the original series of Jack Aubrey novels, Patrick O’Brian. Nicholas’ mid-18th century navy is one that is pre-ideological, and has a pre-rigid class organization. Some of this still applied in the first decade of the nineteenth century and this is where Master and Commander is right to show the legacy – even if the navy was changing. There was in the navy of Nelson an officer who flew his flag at sea as, I think, a vice admiral, who had been flogged around the fleet as a naval seaman for desertion. He was a real person and ended up as Knight Commander of the Bath – Sir William Mitchell. Now, what I am getting at is the pre-ideological situation of circa 1760, in that you have a navy which is based on mutual confidence, mutual respect and professionalism. We talk about patronage, and yes, if you were from the upper class and had good connections, it was much easier to get ahead. But if you were incompetent, you generally didn’t get ahead, since if you are the First Lord of the Admiralty or a commander-in-chief, and you are promoting people who are idiots, your ships won’t last. They’ll sink for a start just from the effects of weather, they won’t be able to capture the enemy, and so on. However, late on in the eighteenth century, what you begin to get, and the American revolution marks the first rumblings of this (it really sets in after the French revolution), is that ideology and class and the fear of subversion become factors. In the navy that Nicholas Rodger talks about it was OK to mutiny in certain circumstances – if you haven’t been paid for instance. If the food was bad. And it is very interesting, in that navy, that if there were a mutiny for other reasons the Admiralty usually fired the captain, however harshly they dealt with the ringleaders. Because, if there were a mutiny for other reasons than pay or food – or losing accustomed officers – the Admiralty’s assumption was it was resulted from a failure in leadership. I hope you begin to see where I am coming from. When we are in are a post-ideological, post-class system in 2016, what do we actually base our navy on? We base it on mutual respect and professionalism and support for each other. And if there is a problem in a ship, how do the admiralties of the western navies now generally respond? They fire the captain. In between, roughly from 1800 to 1990, when you have ideology, subversion and all the rest of it, there is always this idea that a mutiny will have external motivations. In such circumstances, admiralties may have to support the command because they have to support the system. That’s not the case now. What I am seeing in The Wooden World that Nicholas Rodger is telling me about is a navy that I recognize, much more in certain ways than the navy of the centuries in between.

really good book for naval officers to read, is because Master and Commander is slightly anachronistic. What Nicholas is talking about in The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy is the mid-18th century Royal Navy, although Peter Weir and Russell Crane applied it to the service of the Napoleonic Wars as, arguably, did the author of the original series of Jack Aubrey novels, Patrick O’Brian. Nicholas’ mid-18th century navy is one that is pre-ideological, and has a pre-rigid class organization. Some of this still applied in the first decade of the nineteenth century and this is where Master and Commander is right to show the legacy – even if the navy was changing. There was in the navy of Nelson an officer who flew his flag at sea as, I think, a vice admiral, who had been flogged around the fleet as a naval seaman for desertion. He was a real person and ended up as Knight Commander of the Bath – Sir William Mitchell. Now, what I am getting at is the pre-ideological situation of circa 1760, in that you have a navy which is based on mutual confidence, mutual respect and professionalism. We talk about patronage, and yes, if you were from the upper class and had good connections, it was much easier to get ahead. But if you were incompetent, you generally didn’t get ahead, since if you are the First Lord of the Admiralty or a commander-in-chief, and you are promoting people who are idiots, your ships won’t last. They’ll sink for a start just from the effects of weather, they won’t be able to capture the enemy, and so on. However, late on in the eighteenth century, what you begin to get, and the American revolution marks the first rumblings of this (it really sets in after the French revolution), is that ideology and class and the fear of subversion become factors. In the navy that Nicholas Rodger talks about it was OK to mutiny in certain circumstances – if you haven’t been paid for instance. If the food was bad. And it is very interesting, in that navy, that if there were a mutiny for other reasons the Admiralty usually fired the captain, however harshly they dealt with the ringleaders. Because, if there were a mutiny for other reasons than pay or food – or losing accustomed officers – the Admiralty’s assumption was it was resulted from a failure in leadership. I hope you begin to see where I am coming from. When we are in are a post-ideological, post-class system in 2016, what do we actually base our navy on? We base it on mutual respect and professionalism and support for each other. And if there is a problem in a ship, how do the admiralties of the western navies now generally respond? They fire the captain. In between, roughly from 1800 to 1990, when you have ideology, subversion and all the rest of it, there is always this idea that a mutiny will have external motivations. In such circumstances, admiralties may have to support the command because they have to support the system. That’s not the case now. What I am seeing in The Wooden World that Nicholas Rodger is telling me about is a navy that I recognize, much more in certain ways than the navy of the centuries in between.

What advice would you give to a junior or senior officer on how to use history to think about our current challenges in the naval profession?

I like the aphorism “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” You use history to identify the rhymes, to start identifying the questions that you should be asking.I’m particularly seeing rhymes when we look at the First World War and many of the challenges we face now. And many of these challenges are caused by technological change, but the key shared issue is command and control. I think we are facing some real problems of a similar nature to 1914 at the moment. We have got ourselves used to an uncontested electronic environment and a virtual reality which allows constant communication between commands and subordinates. That creates two problems: the one that gets talked about most frequently is the “thousand mile screwdriver.” But there is another problem that worries me even more and this is also a World War I problem – subordinates won’t make a decision; many would rather ask permission than seek forgiveness. And that I think creates the prospect that if communications are cut off, operations will be paralyzed because people will wait and see if communications become reestablished rather than do anything themselves. The direct parallel is the effect of radio on naval culture in 1914. Before radio, it was inherently bipolar. If you were in sight of the admiral you were doing exactly what the admiral directed. But if you were not in sight of the admiral before radio, you knew what the intent was, and you went. As one British prime minister of the nineteenth century remarked, if he had a problem overseas, he’d send a naval officer.

Your latest book is about The Battle of Jutland?

It predates Jutland; it’s about the opening months of the war and is called Before Jutland. One of my arguments is that there were failures of leadership which were based on this “virtual unreality.” I can see why people are failing to exercise initiative which I am pretty sure wouldn’t have been the case to the same extent had there been no radio. The problem was that, with the introduction of radio, when the practical problems and the associated concepts had still to be worked through – and the conceptual changes in particular were profound – detached commanders began to behave in the way that they would when they could actually see their boss. People acted as if they could see the admiral and get an immediate direction to go here or there, and they also assumed the admiral had the picture they have.

is that there were failures of leadership which were based on this “virtual unreality.” I can see why people are failing to exercise initiative which I am pretty sure wouldn’t have been the case to the same extent had there been no radio. The problem was that, with the introduction of radio, when the practical problems and the associated concepts had still to be worked through – and the conceptual changes in particular were profound – detached commanders began to behave in the way that they would when they could actually see their boss. People acted as if they could see the admiral and get an immediate direction to go here or there, and they also assumed the admiral had the picture they have.

To be fair, there was a whole raft of unrecognized problems of understanding on how people talked to each other remotely. That was another art and another science that had to be learned, effectively from scratch. For example, the first time the Royal Navy issued a format for radio reporting of an enemy contact there was no position. Why? Because when you are in a visual environment you are really only interested in two things: what the enemy bear and what they are steering. It is remote reports, with the much greater distances involved, that require much greater detail and precision. The fact was that the out-of-sight admiral did not have the full picture in 1914. Arguably, given transmission delays, deficiencies in reporting systems and the combined navigational errors both true and relative, he could never, at least in 1914-18, have that full picture.

You can also see in 1914 an essentially arithmetical approach to the correlation of forces. What I mean by that: It is a simplistic approach, the idea that if someone has a long range and a longer gun, we can’t go for

them. This happened during the chase of the German battlecruiser Goeben in the Mediterranean in August 1914 and it also happened more than once in the North Sea. Sorry, but, as Nelson used to say, “something must be left to chance.”

Another thing that is similar in 1914 to now, is how short of money the navies were at the time. We talk about the great expansion, the arms race, and it’s absolutely true that enormous amounts of money were being spent. Both the Germans and the British had budgetary crises over such expenditure. But the money is going to the battle fleets, not operations. The British are enforcing strict fuel economy. Why? Because they are building fifteen inch gun battleships which cost the earth, as does oil fuel. There is a major cabinet crisis going on about the naval estimates and the Admiralty has to make economies where it can. So you have limited time at sea and limited exercises in a period of very rapid technological change. You haven’t got the ability to exercise sufficiently, to experiment sufficiently, to become proficient enough to even understand the risks. Arguably, the Germans were even more constrained and thus even worse off.

Now to tie your earlier comments about the challenges of radio and command and control in World War I to today. Is flexibility, and the assumption that you are not going to have secure communications, those assurances, are those the going in conversation?

I’m old enough to remember having to navigate out of sight of land for extended periods of time with no artificial aids. When people talk about the revolution in military affairs, I go, come on guys, the first naval combat data systems went operationally to sea about 1960. The data links were running about 1961-1962. The revolution in military affairs is not computer systems and it is not data links – it’s GPS. Because GPS puts everybody in the same constant frame of reference. Trust me. Try doing a link picture before GPS. Manually updating and watching your whole system slide sixty miles, and all of the other problems that occur if one ship fails in reporting or muddles its settings. Same with joint fires; it’s all GPS. OK. So what happens if you are in a contested environment and your GPS doesn’t work? I think we are coming to an era where we will be very vulnerable if we go on this way. The truth is that you won’t be able to do the things that you think you can.

That similarity with the First World War – I mean – do you know what the most useful thing in navigation was in the First World War in the North Sea? Depth soundings. Bathymetry. What did the British do? What are they doing enormous amounts of from about 1908 on? They are surveying the North Sea to get the depths and the currents. These are things we don’t think about anymore because we don’t have to. But the trouble is I think we have to think about these things because the remote data sources will not necessarily be accessible in a contested electronic environment. As I understand it, the United States Naval Academy is going back to teaching astro-navigation.

What are the top three history books that you’ve read and that you would recommend to anyone?

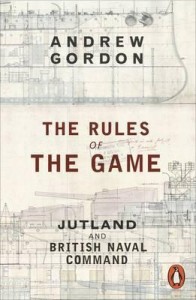

The Rules of the Game by Andrew Gordon is one of them. I was really pleased to be sitting on one occasion with my chief of the navy and Vice Admiral Art Cebrowski. Both had read the book and were talking about the take-aways from The Rules of the Game. Next, is Nicholas Rodger’s naval history of Britain that I’ve already mentioned. My third book would probably be one of Norman Friedman’s works. Which one would depend who you are. For me personally, one of the highlights is his U.S. Destroyers book. It encapsulates all the best that Norman does in terms of understanding how a design evolves, what the operational factors are, the financial factors, etc. I would also say his book on interwar aircraft carrier development is really worth reading (American & British Aircraft Carrier Development 1919-1941). See, one of the real problems is hindsight, and not understanding that things change and that they change in relation to each other. What Norman conveys really well is that there are always changing variables. He explains very well why the Brits got some things wrong in naval aviation, but often for very good reasons that were valid at the time.

was really pleased to be sitting on one occasion with my chief of the navy and Vice Admiral Art Cebrowski. Both had read the book and were talking about the take-aways from The Rules of the Game. Next, is Nicholas Rodger’s naval history of Britain that I’ve already mentioned. My third book would probably be one of Norman Friedman’s works. Which one would depend who you are. For me personally, one of the highlights is his U.S. Destroyers book. It encapsulates all the best that Norman does in terms of understanding how a design evolves, what the operational factors are, the financial factors, etc. I would also say his book on interwar aircraft carrier development is really worth reading (American & British Aircraft Carrier Development 1919-1941). See, one of the real problems is hindsight, and not understanding that things change and that they change in relation to each other. What Norman conveys really well is that there are always changing variables. He explains very well why the Brits got some things wrong in naval aviation, but often for very good reasons that were valid at the time.

There is another wonderful history book, and it is sort of a joke about British cultural education. It’s a book called 1066 and All That. It is a satire of history. It is written by two guys, who I think were middle and secondary school history teachers. It’s called 1066 and All That  because the book is about the history that people remember, not what they were taught. The authors called it that because they reckon that 1066 is the only date in British history that all Brits would remember from their school days. And there is a great quote in the book about “The Irish Question.” And it is worth thinking about: “The English never settled the Irish question because every time the English found the answer the Irish changed the question.” Naval policy and force structure development are a bit like that.

because the book is about the history that people remember, not what they were taught. The authors called it that because they reckon that 1066 is the only date in British history that all Brits would remember from their school days. And there is a great quote in the book about “The Irish Question.” And it is worth thinking about: “The English never settled the Irish question because every time the English found the answer the Irish changed the question.” Naval policy and force structure development are a bit like that.

World War I produced some of the best poets in the English language. Do you read poetry?

I do enjoy it. I have a number of anthologies. I particularly like Field Marshal Wavell’s anthology, Other Men’s Flowers. If there is a poet of the navy, it’s actually  Rudyard Kipling. Kipling wrote about the navy very sympathetically and very well. Kipling is the poet of technology; he’s the poet of the engineers. And he is also the poet of commanders – “The Song of Diego Valdez” and its examination of the “bondage of great deeds” is worth reading carefully.

Rudyard Kipling. Kipling wrote about the navy very sympathetically and very well. Kipling is the poet of technology; he’s the poet of the engineers. And he is also the poet of commanders – “The Song of Diego Valdez” and its examination of the “bondage of great deeds” is worth reading carefully.

Of course the naval experience was never the same as that of the army, and in many ways the education you needed in the navy was not the same in the army. The navy didn’t get that sort of flower of a generation from liberal arts universities that the army did in 1914-18. They didn’t get the Siegfried Sassoons, Robert Graves, and all the rest. However, rather than poetry, when I lecture on leadership, particularly at the staff course to all three services, I suggest officers read these works:

For the army, I suggest a book by John Masters. He wrote Nightrunners of Bengal and other stuff. Masters was an Indian Army lieutenant colonel at the age of thirty-two, and he earned a DSO and an OBE by the end of World War II, having been one of the leaders of Wingate’s Chindits in Burma. I recommend his book called Man of War. It is set in pre-Dunkirk France. It’s about a lieutenant colonel who ends up running a battalion group. And it is based on history. He faces off against Rommel. Army officers like it because it is a great book on that level of command.

For the navy, I recommend The Cruel Sea by Nicholas Monsarrat. He was a volunteer, a reservist, who started his war with complete inexperience as a sub-lieutenant and finished it commanding a frigate. So he understands his subject, leadership at sea in the Battle of the Atlantic. Another is Herman Wouk’s Caine Mutiny, which I would put in the same league. It is the study of leadership in a slightly different context, but very valuable for all that. Herman Wouk did the same as Monsarrat, he served in the Pacific War as a reserve officer. I met him many years ago when he visited Australia and he told me that he had to write this book, but he was terrified how it would be received. You know, that the US Navy (which he loved) would never talk to him. Instead what happened was that The Caine Mutiny was published and became a best seller very quickly. And then for six weeks after it came out there was a deathly silence; none of his navy friends would talk to him. Wouk was thinking “Oh God.” Then someone asked the then-CNO publicly if he had read the book. And the CNO said “It’s a great book! I’ve met every one of the single people in that book, not on the same ship, but I’ve met all of them – it’s a great book.” Herman Wouk told me he breathed a huge sigh of relief after hearing that.

Now, for air power, you should read the book Twelve O’clock High. And actually, I recommend you watch the film as much as reading the book because the men who wrote the book wrote the film script. And both of them had done full deployments in the US Army Air Corps in the bombing campaign over Europe. In theory it is a high command novel, but in reality it isn’t, it’s about unit command in attrition warfare.

All these works convey a reality of the experience of command and war that in some ways expert fiction can do more easily than history. If you read all of these books seriously, they’ll tell you the sort of things you should be thinking about.

What is the best Nelson biography you would recommend? Other biographies you recommend?

Roger Knight’s The Pursuit of Victory: The Life and Achievement of Horatio Nelson. Very good indeed; Head and shoulders above others. I also think that Andrew Lambert’s Admirals book is very good – especially about his nineteenth century subjects. I also recommend that every US naval officer read Admiral Elmo Zumwalt’s book On Watch. Zumwalt made his mistakes as CNO from 1970 to 1974. And of course he won’t admit many of them in his autobiography. But, as the story of a genuine change effort as well as some interesting – and continuing – naval problems and how you deal with them, it is a very worthwhile read. If you think of the subtext, and then you go and read other stuff, you can see he is sort of admitting that where he failed is engaging commissioned and noncommissioned leaders. The US Navy was in a bad state in 1970 and something had to be done. Navies can get disconnected from the culture of their nations. This is not to do with standards or things like that. It has more to do with cultural mores. It’s the old thing about are you allowed to wear jeans as a liberty uniform? If jeans are the accepted thing in society…well, then, yes, you should be.

What four people from history would you have at your dinner table? And why?

If I start with Americans, William S. Sims. I suspect I would like to have dinner with Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt. And I admire Harry S. Truman – he and the other two presidents were all readers, too. Next, I’d like to meet Nelson. Whatever Nelson had, the really striking thing about him is that he had this extraordinary ability that if the enemy did anything wrong Nelson went straight at them. Nelson led at all levels. Everybody working for Nelson loved him. And he was, by all accounts, a great host at dinner himself!

As a historian digging into the archives, and as you’ve studied history, what are those things that you’ve touched and read that reminded you why you love being a historian?

Yes, there is that moment when you find something that nobody else has looked at before. When you find something, a particularly important piece of evidence…there is one I found about the Battle of the Dogger Bank in January 1915. It was in Beatty’s flag commander’s recollections written within two days of the battle – and nobody had picked up on this. They were written before they got back in harbor. There is a key narrative there about one vital tactical decision in the battle. And if you read this you understand very differently why and how everybody else reacted.

Another thing I ended up getting heavily involved in when doing research for World War I, was coal. Coal turns out to be fundamental. I ended up writing an academic paper on it because it was so important (“Coal and the Advent of the First World War at Sea“). It’s all to do with the sort of coal you used. First, it is about understanding how the ships worked. You now we have this picture of it being the boilers and the stokers…well, that’s not the problem. The problem is the bunkers, and what’s called trimming. It’s getting the coal from the bunkers to the stoke hold, that’s the problem, not shoveling it into the boilers. In fact, quite a lot of the deck crew had to support trimming operations. And because of this, the British had to change their manning to support trimming. In World War I, for all major units, the last 25% of the coal was inaccessible if they were doing any sort of reasonable speed. They couldn’t get the coal from the bunkers to the stoke holds fast enough. That problem started at 60% capacity with the battle cruisers.

Then you get into types of coal. The right coal for a warship boiler is what’s called semi-bituminous coal. There is one area which produces the best such coal in the world – and it’s a particular section of the Welsh coal fields. There were 40 collieries which produced what was called “Admiralty coal.” Now, outside of them, are what’s called “steam coal” areas. It’s still pretty good coal, but the Admiralty coal burnt producing almost no smoke (and that’s really important for its effect on visibility in battle). Furthermore, the coal lumps were the right size, and they “cauliflowered” – as the Admiralty coal heats up the top breaks open which actually increases the surface area and increases the efficiency of combustion. Admiralty coal is what the Royal Navy used. Basically, the difference in coal performance was – and here I have the Australian figures – because for this purpose [powering warships] Australian coal was crap. When the battle cruiser Australia arrived in Australia in 1913, naturally enough, the Australian government wanted it provided with Australian coal rather than Welsh Admiralty coal because Welsh Admiralty coal was much more expensive. Now, Australia, with 31 boilers on Admiralty coal alone, could do 26 knots. Using Australian coal, with supplementary oil firing, on all boilers, she could barely do 15 knots and her range was reduced by 40%-50%; and in fact, even then she would start having incredible problems with the boilers choking…with ash and debris buildup.

Circumstantial evidence supports my contention that the Imperial German Navy did their high-speed steam trials using Welsh admiralty coal. Knowing the German Navy was a political institution and that its official history Der Krieg zur See was written with an eye to encouraging Germany to rearm, it is not surprising that this doesn’t get a mention. I think what happened is that they were embarrassed, because this is not something you can admit, you know, you did your power trials with your prospective enemy’s fuel source. The German battle cruisers could do 28 knots during sea trials. As far as I can figure in an operational environment, no German major unit never achieved more than 24 knots sustained. And in every German operation the ships are complaining about the quality of coal, because they are using Westphalian coal. So you have serious operational implications. It’s actually when you look at this closely that it does matter.

Sir, thank you for your time.

Thank you.

Rear Admiral James Goldrick, RAN(ret.), AO,CSC joined the Royal Australian Navy in 1974 and retired in 2012 as a two star Rear Admiral. He is a graduate of the RAN College, the Harvard Business School Advanced Management Program, the University of New South Wales and the University of New England, and a Doctor of Letters honoris causa of UNSW. He commanded HMA Ships Cessnock and Sydney (twice),

the RAN task group and the multinational maritime interception force in the Persian Gulf (2002) and the Australian Defence Force Academy (2003-2006 and 2011-12). He led Australia’s Border Protection Command (2006-2008) and the Australian Defence College (2008-2011). He is a Fellow of the RAN’s Sea Power Centre-Australia, a Non-Resident Fellow of the Lowy Institute for International Policy, Adjunct Professor of UNSW at ADFA and SDSC at The Australian National University and a Professorial Fellow of the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security. In the first half of 2015 he was a Visiting Fellow at All Souls College in the University of Oxford. James Goldrick’s books include: The King’s Ships Were at Sea: The War in the North Sea August 1914-February 1915 and No Easy Answers: The Development of the Navies of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and, with Jack McCaffrie, Navies of South-East Asia: A Comparative Study. His latest book is Before Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters, August 1914 — February 1915. The comments above are the author’s own.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson, USN, is an intelligence officer stationed at the US Pacific Fleet Headquarters in Honolulu, Hawaii. Lieutenant Commander Nelson is a graduate of the US Naval War College and the navy’s operational planning school, the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island. The comments above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Department of Defense or the US Navy.