By Frank A. Blazich, Jr.

In an era where the Navy is facing contested seas from challenges posed by China and Russia, history can unlock potential advantages with which to meet current and future threats. Gathering and preserving its operational records, in essence data, is critical. Unfortunately, in terms of such historical records, the Navy is in the Digital Dark Age. It retains only limited data and is losing access to its recent history – knowledge purchased at considerable cost. The Department of Defense and the Navy must consider a cultural and institutional revival to collect and leverage their data for potential catalytic effects on innovation, strategic planning, and warfighting advantages. This cultural transformation of collecting and preserving historical data within the Navy will be a long process, but leveraging its history to meet current and future problems will aid in maintaining global maritime superiority.

On 25 May 2006, Navy Expeditionary Combat Command (NECC) formally established Riverine Group 1 and Riverine Squadron 1 to safeguard the inland waterways of Iraq. These lethal, agile forces executed over 2,000 missions and trained their Iraqi River Police successors to carry on after the withdrawal of major American forces. The experiences of the Navy’s Coastal Surveillance Group (TF-115), River Patrol Force (TF-116), and Mobile Riverine Force (TF-116) which operated in the Republic of Vietnam in the 1960s, facilitated the establishment of these forces. The records collected, organized, and preserved by Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) and command-published histories of the brown- and green-water force enabled NECC to expedite the efficient launch of a riverine force for the 21st-century Navy.1

History is one of the fundamental sinews of the American military establishment. Training is informed by “lessons learned” from prior experiences—historical data by another name—and every organization has senior members who contribute decades of institutional memory to solve contemporary problems. Synthesized into history monographs, these publications equip warfighters with insight and perspective to better guide their actions and decisions. Avid history reader and retired Marine General James Mattis acknowledges, “I have never been caught flat-footed by any situation, never at a loss for how any problem has been addressed (successfully or unsuccessfully) before.”2 History’s importance to the present Navy is also reflected in Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral John M. Richardson’s Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, which states “we must first understand our history – how we got to where we are.”3 The CNO’s recently released professional reading program buttresses his statement with a rich and varied roadmap of texts which have influenced his leadership development.4

Today, the Navy finds itself returning to an era of contested seas with contemporary challenges posed by China and Russia. Throughout the Cold War, the Navy possessed a large body of veteran Sailors holding vast reserves of institutional memory, often stretching back to World War II, in all aspects of naval operations. Deployments from Korea to Vietnam and from the Mediterranean to the Arctic Ocean honed the Navy’s capabilities. The subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union provided the Navy with a period of uncontested naval supremacy, but also led to force reductions and a gradual loss of institutional experience with missions like hunter-killer groups, offensive mining, and large surface action groups. A dwindling number of active duty Sailors have operational Cold War experience, and they mostly occupy senior leadership positions.

The records needed to fill that gap must be preserved. Through the Vietnam War, the Navy’s historical data principally took the form of written correspondence in varied formats. The advent of digital computing has vastly transformed record generation and retention, both of which pose notable challenges to records management.5 In a period of important fiscal and strategic decisions, the Department of Defense and the Navy must consider a cultural and institutional revival to collect and leverage data for potential catalytic effects on innovation, strategic planning, and warfighting advantages.

Gathering the Data

Several efforts currently exist to capture the Navy’s data. The lifecycle of records is governed by the Department of the Navy Records Management Program, which establishes all policies and procedures for records management. Under the Director of Navy Staff is NHHC, whose mission is to “collect, preserve, protect, present, and make relevant the artifacts, art, and documents that best capture the Navy’s history and heritage.”6 Naval Reserve Combat Documentation Detachment (NR NCDD) 206, established following Operation Desert Storm, assists NHHC personnel by providing uniformed teams for deployment to fleet units and other Navy commands to document and preserve the history of current naval operations during crisis response, wartime, and declared national emergencies. They are actively engaged in supporting NHHC’s mission objectives.7 Lastly, an essential tool for collecting the Navy’s historical data is Office of Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) Instruction 5750.12K governing the production of the annual Command Operations Report (COR).

First published on 8 November 1966, OPNAVINST 5750.12 governs creation of the COR, intended to ensure historical records are available for future analysis.8 As stated in the current version, the COR “is the only overall record of a command’s operations and achievements that is permanently retained” and provides “the raw material upon which future analysis of naval operations or individual unit operations will be based.”9 The document primarily consists of a chronology, narrative, and supporting documentation. As OPNAVINST 5750.12 evolved, emphasis shifted from gathering information on specific subjects relevant to warfighters and combat operations to becoming a tool to gather specific types of documents.10

Unfortunately, compliance is erratic and the instruction’s importance was ignored (or unknown) by commands. From 1966 to the present, the submission rate of CORs for units and commands has never reached 100 percent; for CY15 the submission rate stood at 63.5 percent. Submitted CORs are often unevenly written and composed. The causes for these shortfalls vary and are undefined. The culprits are likely operational tempo, personnel shortfalls, and/or concerns about information security. Perhaps commanders opted to err on the side of caution and avoid objectively documenting an unsuccessful operation, intra-service conflict, or inadequate leadership. Without foreseeing the potential impact and importance a COR may have on tomorrow’s Navy, responsibility for the report is often assigned as an additional duty for a junior officer juggling a myriad of responsibilities.

These data gaps have an adverse impact on present and future actions at both the individual and institutional level. For veterans, a gap in COR submissions may result in the denial of a benefits claim with the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, or in regard to awards or decorations with the Board for Correction of Naval Records.11 For OPNAV, Fleet Forces Command, Pacific Fleet, or numbered fleets, lost CORs diminish the raw data needed for quality analysis, leaving analysts to generate products which may fail to accurately account for critical variables. What is lost is critical contextual information, retention of which is invaluable. “Solid historical record-keeping and analysis would help enlarge decision makers’ perspectives on current issues,” writes historian and retired Navy Captain David Rosenberg.12 Without rigorous records, historians such as Rosenberg cannot write books and articles to help leaders like Secretary Mattis and warfighters sufficiently learn about previous military endeavors. Consequently, past mistakes will inevitably be repeated with potentially adverse outcomes.

Current COR generation is arguably more difficult than ever. The information revolution has led to the proliferation of raw data without the benefit of summation or prior analysis. PowerPoint slide decks, rather than correspondence or memoranda, are all that an author or veteran might possess on a given topic. Rather than gathering critical teletypewriter message traffic from an operation, the author of a COR might need to collect email correspondence from multiple personnel throughout a unit bearing an array of security classifications. Gathering information from digital discussion boards, section newsletters, and untold quantities of data could be a full-time job.

Furthermore, the follow-on process of creating a coherent narrative from the raw data is a laborious process for a professional historian, much less for a Sailor fulfilling an additional duty and unfamiliar with the task. During World War II, the usual authors of aviation command histories were squadron intelligence officers. They understood how the information collected could be used for everything from operations to force development to technical improvements. Coupled with a familiarity of preparing narrative analyses and summary papers, the resulting command histories proved cogent and comprehensive. By comparing old and contemporary CORs, it is obvious that commanders must assign the COR responsibility to qualified individuals with the appropriate education, experience, and skills.

Increasing the operational tempo of naval forces naturally increases the generation of data. However, with limited time and personnel to gather and generate the data, it must come as no surprise that records about the Navy’s involvement in Operations Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Iraqi Freedom (OIF) have been irretrievably lost, to incalculable impact. Valuable Navy operational records from OEF and OIF do exist, but the data belongs to the respective combatant commands and is currently inaccessible to Navy analysts and research specialists.

The Past is Prologue

No individual or organization is infallible—errors can be extremely costly, and for military organizations they lead to the loss of blood and treasure. The operational records generated in peace and wartime provide raw materials for historical analysis, which distill lessons learned and generate studies to educate uniformed personnel. Mistakes always happen, but historical analysis can prevent the repetition of old errors. Incomplete data yielding subpar analysis will affect the resultant knowledge products and undermine history’s influence on future decisions. For example, in 1906, Lieutenant Commander William S. Sims incorporated battle observations and gunnery data to challenge the conclusions of Captain Alfred T. Mahan regarding gunnery at the Battle of Tsushima and advocated convincingly for a future fleet design dominated by all-big-gun battleships, thereby ushering the Navy into the “Dreadnought era.”13 If the operational records of current efforts are being lost, are we not again jeopardizing future fleet designs?

Analysis of combat operations has proven instrumental in improving the warfighting abilities of the respective services. Combat provides the only hard evidence on the effectiveness of military doctrine and the integration of platforms and weapons. For example, the Battle of Tarawa (20-23 November 1943) tested the doctrine of amphibious assault against a fortified position. As historian Joseph Alexander details in his book Utmost Savagery, success in the amphibious invasion remained an “issue in doubt” for the Marines for the first thirty hours. The documentation and analysis of the battle prompted the Navy and Marine Corps to increase the amount of pre-invasion bombardment and to refine key aspects of their amphibious doctrine, among other changes. With evidence-turned-knowledge gleaned from Tarawa, the Navy and Marine Corps continued unabated in rolling back the Imperial Japanese Empire, assault by bloody assault.14

Similarly, the Vietnam War demonstrated how technology does not always triumph in an asymmetric clash of arms. In the skies over North Vietnam, American aircraft armed with sophisticated air-to-air missiles met cannon-firing MiG fighters. Neither the Air Force nor Navy enjoyed a high kill ratio, which at best favored them two-to-one until the cessation of Operation Rolling Thunder in November 1968. Disturbed by the combat results, CNO Admiral Tom Moorer tasked Captain Frank Ault to examine the Navy’s entire acquisition and employment process for air-to-air missile systems. After examining reams of available historical data, Ault’s May 1968 report recommended establishing a school to teach pilots the advanced fighter tactics of a seemingly bygone age of machine gun dogfights. This recommendation gave birth to the Navy Postgraduate Course in Fighter Weapons Tactics and Doctrine better known as TOPGUN. Using a curriculum developed by studying operational records, TOPGUN’s first graduates entered air combat over North Vietnam after the resumption of bombing in April 1972. When American air operations ceased in January 1973, the Navy enjoyed a kill ratio of six to one, due in large part to TOPGUN training in dogfighting and fighter tactics.15

Carrier aviation’s successes in OEF and OIF came in part due to the lessons gleaned from Operation Desert Storm (ODS). With carrier doctrine designed for blue water sea control against the Soviet Navy, the force was not tailored for sustained combat projection onto land. In the waters of the Persian Gulf and Red Sea in 1990-1991, however, six carrier battle groups found themselves operating in a coalition environment. Despite the lofty hopes envisioned with the passage of the Goldwater-Nichols Act in 1986, naval aviation found itself unprepared for joint and coalition interoperability. From the lessons of ODS, the Navy modified its F-14s to carry the Air Force’s LANTIRN targeting system, began purchasing precision-guided munitions, and modified the carrier air wing composition to better support operations on land per joint recommendations. From Operation Allied Force in 1999 to the launch of OEF and OIF in 2001 and 2003, respectively, naval aviation flew substantial numbers of deep-strike missions, fully integrated into joint and combined air operations.16

The History You Save Will Be Your Own

In terms of historical records, today’s Navy is in the Digital Dark Age, a situation drastically accelerated within the past twenty years by the immense generation of digital-only records. It retains only limited data and the service is actively losing access to its recent history, knowledge purchased at considerable cost. Valuable Navy operational records from OEF and OIF do exist, but the data is unobtainable from the combatant commands. Although COR submissions in the first year of each conflict were higher than in peacetime, they thereafter fell below a fifty percent submission rate. In some cases, there are no records of warships assigned to carrier strike groups for multiple years. While some data was captured, such as electromagnetic spectrum or targeting track information, the records involving “who, what, where, when, why, and how” are lacking. NR NCDD 206, together with NHHC staff, conducts oral histories with Sailors to collect data that researchers can use to capture information not included with CORs. Oral histories, however, supplement but do not completely substitute for textual records.

What exactly is being lost? Why does this matter if weapon- and platform-related data is available? The intangibles of decision-making and the organizational culture are captured in data generated through emails, memoranda, and operational reports. For example, as the Navy evolves its doctrine and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) to maximize the potential of the distributed lethality concept, issues of decentralized command and control must be addressed.17 The ability to draw upon historical data to inform TTPs, training systems, and cycles is paramount to prepare commanding officers and crews for potential challenges over the horizon and to close learning gaps. As retired Marine Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hoffman notes, the World War II submarine community drew extensively upon the after-action and lessons learned reports to improve TTPs and promulgate best practices to educate the entire force.18

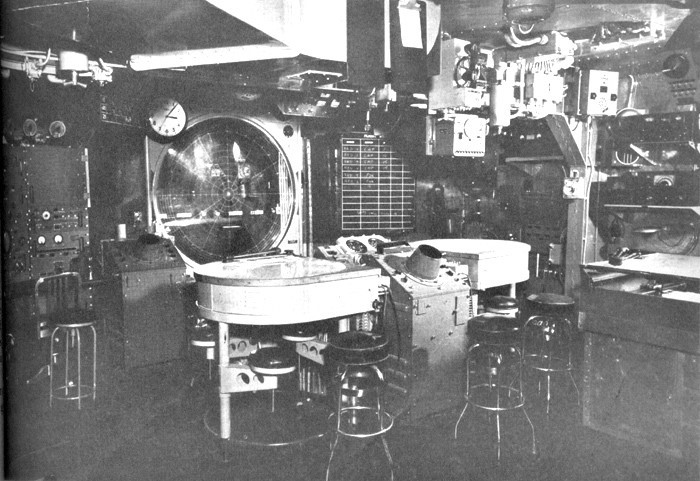

Navy culture successfully adapted to close learning gaps in World War II, and it can adapt to escape the Digital Dark Age. In the 1920s and 1930s, budgetary and treaty restrictions limited fleet design but the Navy experimented, evaluated, and used its data to improve its platforms and TTPs. One notable example was the evolution of how ships processed information at sea, culminating in 1944 with the Combat Information Center, an integrated human-machine system which Captain Timothy Wolters documents in his book, Information at Sea, as an innovative example of decades of research and development informed by history.19

Preserving critical historical data is the collective and legal responsibility of every Sailor and Department of Navy employee. Digitization poses challenges that cannot be met by only a small group of historians and archivists, a form of “distributed history.” If distributed lethality enables every ship to be a lion, digitization and computer-based tools enable every Sailor to take ownership of their unit’s accomplishments and play an active role in the generation of the COR. Command leadership must advocate for the COR rather than considering creation as merely an exercise in annual compliance. Responsibility and management of the annual COR must be a team effort. Include chief petty officers and junior enlisted and empower them to take an active role in collecting data and drafting the chronology and narrative. Not only must the COR be an objective, factual account but an inclusive report with contributions by officer and enlisted communities to ensure preservation of a thorough record of all actions, accomplishments, and key decisions.

Furthermore, data is generated continuously. A quality COR is rarely written following a frantic flurry of electronic messages requesting people forward files to the designated COR author. Assembling a dedicated COR team of officers and enlisted personnel to gather and organize records throughout the year will prove more beneficial. This team in turn can provide a valuable resource for an entire crew and commander, either to provide information for public relations, morale purposes, award nomination packets, or operational analysis.

Classified material poses an immediate concern when proposing this distributed history approach for COR generation. Such digital records, located on a variety of computer networks, rightfully pose challenges regarding operational security, either via aggregation or unauthorized access. Such concerns should not, however, jeopardize the overall effort. Generating classified CORs is encouraged and detailed in OPNAVINST 5750.12K; as thorough a narrative as possible is essential. Archivists at NHHC, trained to process and appropriately file classified material, can provide guidance to ensure the security and integrity of the data. When concerns over security result in a banal, unclassified COR, data about that unit’s activities is forever unavailable to the Navy for use in addressing future innovations, conflicts, or organizational changes, and the report’s utility to OPNAV, researchers, and veterans becomes essentially nil. With budgetary difficulties affecting the Navy, data—classified or not—serve as an intellectual, institutional investment for the future. In explaining to the Congress and the American people how and why the Navy is responsibly executing its budget for the national interest, availability and utilization of the data is paramount for the task.20

Conclusion

Transforming the Navy’s culture of collecting and preserving its historical data will be a long process. Digitization and the increasing volume of records will continue to pose challenges. These challenges, however, cannot be ignored any longer and require a unified front to ensure records are preserved and available for use. The Navy is not alone; its sister services experience similar problems in collecting data and using it to benefit current operations.21 In an era where reaction and decision times are rapidly diminished through advances in machine-to-machine and human-machine interactions, today’s data may help equip the warfighter with future kinetic or non-kinetic effects. As fleet design and tactics evolve to face new threats, the Navy can ill afford to ignore its past investments of blood and tax dollars. It must leverage its historical data to find solutions to current and future problems to ensure continued maritime superiority.

Dr. Frank A. Blazich, Jr. is a curator of modern military history at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. After receiving his doctorate in modern American history from The Ohio State University, he worked as a historian for Naval History and Heritage Command. Prior to joining the Smithsonian, he served as historian for Task Force Netted Navy.

Endnotes

1. Robert Benbow, Fred Ensminger, Peter Swartz, Scott Savitz, and Dan Stimpson, Renewal of Navy’s Riverine Capability: A Preliminary Examination of Past, Current and Future Capabilities (Alexandria, VA: CNA, March 2006), 104-21; Dave Nagle, “Riverine Force Marks One-Year Anniversary,” Navy Expeditionary Combat Command Public Affairs, 7 June 2007, http://www.navy.mil/submit/display.asp?story_id=29926; Matthew M. Burke, “Riverine Success in Iraq Shows Need for Naval Quick-Reaction Force,” Stars and Stripes, 29 October 2012, http://www.stripes.com/news/riverine-success-in-iraq-shows-need-for-naval-quick-reaction-force-1.195109.

2. Geoffrey Ingersoll, “’Too Busy to Read’ Is a Must-Read,” Business Insider, 9 May 2013, http://www.businessinsider.com/viral-james-mattis-email-reading-marines-2013-5.

3. Admiral John M. Richardson, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, January 2016), 1, 7.

4. Chief of Naval Operations, “Navy Professional Reading Program” http://www.navy.mil/ah_online/CNO-ReadingProgram/index.html (accessed 18 April 2017).

5. David Talbot, “The Fading Memory of the State: The National Archives Struggle to Save Endangered Electronic Records,” MIT Technology Review, 1 July 2005, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/404359/the-fading-memory-of-the-state/.

6. “Who We Are,” Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/organization/who-we-are.html.

7. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, OPNAV Instruction 1001.26C, “Management of Navy Reserve Component Support to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations,” 7 February 2011, https://doni.daps.dla.mil/Directives/01000%20Military%20Personnel%20Support/01-01%20General%20Military%20Personnel%20Records/1001.26C.pdf.

8. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, OPNAV Instruction 5750.12, “Command Histories,” 8 November 1966, Post-1946 Command File, Operational Archives, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington Navy Yard, DC.

9. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, OPNAV Instruction 5750.12K, “Annual Command Operations Report,” 21 May 2012, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/instructions-and-forms/command-operation-report/pdf/OPNAVINST%205750.12K%20-%20Signed%2021%20May%202012.pdf.

10. Based on a review of OPNAVINST 5750.12 through OPNAVINST 5750.12K, in the holdings of Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington Navy Yard, DC.

11. Eric Lockwood, “Make History: Submit your Command Operations Report,” Naval History and Heritage Command, 10 February 2016, http://www.navy.mil/submit/display.asp?story_id=93031.

12. David Alan Rosenberg, “Process: The Realities of Formulating Modern Naval Strategy,” in Mahan is Not Enough: The Proceedings of a Conference on the Works of Sir Julian Corbett and Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond, eds. James Goldrick and John B. Hattendorf (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 1993), 174.

13. William Sims, “The Inherent Tactical Qualities of All-Big-Gun, One-Caliber Battleships of High Speed, Large Displacement, and Gun-Power” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 32, no. 4 (December 1906): 1337-66.

14. Joseph H. Alexander, Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995), xvi-xvii, 232-37.

15. Marshall L. Michell III, Clashes: Air Combat over North Vietnam, 1965-1972 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 185-88, 277-78; John Darrell Sherwood, Afterburner: Naval Aviators and the Vietnam War (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 219-21, 248.

16. Benjamin S. Lambeth, American Carrier Air Power at the Dawn of a New Century (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2005), 1-8, 100-01; Edward J. Marolda and Robert J. Schneller, Jr., Shield and Sword: The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf War (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1998), 369-75, 384-85.

17. Kit de Angelis and Jason Garfield, “Give Commanders the Authority,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 142, no. 10 (October 2016): 18-21.

18. Frank G. Hoffman, “How We Bridge a Wartime ‘Learning Gap,’” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 142, no. 5 (May 2016): 22-29.

19. Timothy S. Wolters, Information at Sea: Shipboard Command and Control in the U.S. Navy, from Mobile Bay to Okinawa (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2013), 4-5, 204-21.

20. Prior to World War I, the Navy recognized the need to secure public support for its expansion plans. See George W. Baer, One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890-1990 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993), 35-48, 54-63.

21. Francis J. H. Park, “A Time for Digital Trumpets: Emerging Changes in Military Historical Tradecraft,” Army History 20-16-2, no. 99 (Spring 2016): 29-36.

Featured Image: Sunrise aboard Battleship Missouri Memorial at Ford Island onboard Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Katarzyna Kobiljak)