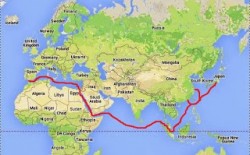

“The Indian Ocean is not just a source of raw materials; it is also a vital conduit for bringing those materials to market. Most notably, it is a key transit route for oil making its way from the Persian Gulf to consumers in Europe and Asia. Seventeen million barrels of oil a day (20 percent of the world’s oil supply and 93 percent of oil exported from the Gulf) transits by tanker through the Strait of Hormuz and into the western reaches of the Indian Ocean. (…) In terms of global trade, the Indian Ocean is a major waterway linking manufacturers in East Asia with markets in Europe, Africa, and the Persian Gulf. Indeed, the Asia–Europe shipping route, via the Indian Ocean, has recently displaced the transpacific route as the world’s largest containerized trading lane.” (A. Erickson: Diego Garcia, p. 23)

German vital interests, shared by its European and global partners, are therefore safe and secure sea-lanes. Needed are stability ashore and the absence of state and non-state sea-control, which could become hostile to German interests. Combating piracy and terrorism as well as contributing to disaster relief and mutual trust building are therefore security challenges Germany must tackle in the Indian Ocean to pursue its interest of geopolitical stability.

|

| Source and legend: Int. Seabed Authority |

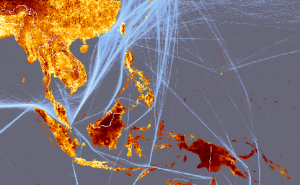

In addition, Germany has also resource interests in the Indian Ocean. Its deep sea is blessed with metal resources and Berlin is already working on gaining exploration rights. German research ships pay regular visits to the Indian Ocean. In the coming run for deep sea resources, Germany will not stay absent. When the deep sea mining starts (probably after 2020), the expensive ships are easy to target and very vulnerable. Due to Rare Earths, Manganese and Cobalt, mining in the Indian Ocean could become of extreme economic importance. Blue-water operating ships need blue-water protection, otherwise pirates, terrorists, criminals or even other states may conclude that the German ships are easy to capture.

Of course, the Indian Ocean’s resources will be subject to international diplomacy. However, diplomacy needs a backbone; often that is an economic, but sometimes it has to be a military one. If all you get from Berlin is words, nobody will pay attention to its interests. Showing the flag is therefore a way to make oneself heard.

It seems that minds are slowly shifting in Berlin towards more German responsibility in international security. Thomas de Maizière, defense minister and potential 2014 NATO SecGen, is arguing for an end of Germany’s “Sonderrolle” and is promoting NATO reform. Moreover, a recent SWP/GMF-report, written by a numerous think tankers and policy-makers from all parties, says that Germany must lead more and show more organic initiative to contribute to a stable international order.During the summer, there were many op-eds in the German press which criticized the government’s passivity in global affairs, with special regard to Syria, and called for a more active foreign policy. One example is a comment published by the Berlin-based newspaper Der Tagesspiegel saying that Germany’s geopolitical reluctance has become grotesque. Slowly, public debate in Germany has started to change.

However, written words do not mean that things get done. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that Emily Haber, State Secretary in the Federal Foreign Office, gave a speech about Germany’s interests in the Indian Ocean. With a strong geopolitical and geo-economic emphasis, Mrs. Haber outlined that “the Indian Ocean will be the new center of the international limelight”. Due to the contrast to what you normally get from many German voices, Mrs. Haber’s speech is definitely worth quoting to show why the Indian Ocean is an area of German interests:

“What is Germany’s interest in that region? Just as China is connected to the Indian Ocean on its Eastern side by the Strait of Malacca, Germany and Europe are connected to it by the Suez Canal on its Western side. Neither China nor Germany is a rim country, but as the world’s strongest export nations we both have an eminent interest in open sea lanes of communication and free trade. (…) If we look at the economic data, Germany is – just like China – a strong trading partner for the Indian Ocean rim countries. Trade and economy hinge on security and stability. We realize that. (…) But when we state our interest in secure and stable conditions for trade and cooperation with Indian Ocean rim countries, and beyond, we believe it goes both ways. After all, we are the world’s largest and arguably most innovative free trade area, and the Indian Ocean is your pathway to it.” (Link)

|

| Source: EUISS Report No. 16, p. 17 |

We see Germany has significant interests in the Indian Ocean. Moreover, these are not in solely national interests, but rather shared with Berlin’s European and American allies and also with Indo-Pacific countries. (Sadly, different from other global capitals, the term Indo-Pacific is not used frequently in Berlin, yet. Even in the academic landscape, watching Asian geopolitics with an Indo-Pacific focus is rare.) It is time that Europe’s present economic powerhouse does its share to contribute active- and globally to a stable international order and to a peaceful use of the global commons. To be taken serious, German foreign policy must deliver more than calls (without consequences) for disarmament and arms control.

Many Germans will scream out loud at the idea of a permanent naval presence in the Indian Ocean. However, widely unrecognized, such a presence already started in 2002 (Operation Enduring Freedom 2002-10, Operation Atalanta 2009-present).In addition, German ships took part in NATO-SNMG port visits in the Indian Ocean. Bi-annually, the German and South African Navies hold joint exercises. After the 2004 Tsunami, a German supply ship went to Indonesia for disaster relief. Most notable, two times German frigates, Hessen in 2010 and Hamburg in 2013, operated in the Arabian Sea over several months in real(!) deployments of US carrier strike groups.

|

| German LHD? Maybe? (Source) |

Worth mentioning is also the Hansa Stavanger incident. In April 2009, Somali pirates captured the German cargo ship and took the crew as hostages. From the US Navy LHD USS Boxer, German special forces (GSG 9) planned an assault to free the hostages. The mission was cancelled by Washington, because the Americans were fed up from political troubles in Berlin about the mission. However, Hansa Stavanger provides two maritime lessons to learn for the Germans. Number one, they need their own LHD/LPD or at least permanent access to one. Number two, a naval presence in the Indian Ocean is necessary not only to protect their interests, but also their fellow citizens (and those of allies and partners). Next time maybe the US Navy will not provide one of their expensive LHDs. The overstretched French and British could be incapable to help out.

Thus, the case for a permanent German naval presence is less spectacular than it seems. This article argues to extend what is already happening since more than ten years. The German Navy should operate one frigate or corvette based in Djibouti, if possible in cooperation with the French and other on-site navies. Submarines, SIGINT ships, surveillance planes and supply ships could be send whenever necessary. As Germany considers buying one or two LPD and developing amphibious cooperation projections with Poland and the Netherlands, a joint German-Dutch-Polish expeditionary task force might be an idea worth discussing.

|

| Location of Diego Garcia (red) |

Instead of Djibouti, the US naval and air base Diego Garcia is a considerable location. Having already cooperated with the US in the Indian Ocean, Germany could base a frigate there. Such a move would strengthen its relationship with its closest non-European ally. Moreover, the US base is more reliable and safer than Djibouti. There is no terrorist threat on the island or the possibility of a government kicking the Germans out. From a strategic perspective, there is no reason why the United States should not welcome a German presence on Diego Garcia, because Europe is much dependent on the Indian Ocean than America.

“However, as noted previously, many of America’s allies and key trading partners in Europe and East Asia are highly dependent on the Indian Ocean for energy. Similarly, with respect to the goods trade, the Indian Ocean is also a far more important conduit for the nations of East Asia and Europe than it is for the United States. Thus the strategic importance of the IOR to the US is not based on its direct impact on America, but on its importance for key US allies and partners. In so far as developments in the IOR affect key allies and partners in Europe and East Asia, who depend on the region energy and trade flows, they are of importance to the United States.” (A. Erickson: Diego Garcia, p. 24)

Any US reluctance to give access to Diego Garcia should be countered with the argument, that it was Washington which was calling for more European and German global engagement. Now, when Germany wants to do something, America should not close the door.

The location in Djibouti is much closer to the vital sea-lanes, while Diego Garcia offers greater flexibility. Therefore, if the German Navy should seek for access to both bases. Diego Garcia is closer to the deep sea claims. However, there will be no German naval operations to secure claims by force. Nevertheless, Germany should be able to act in areas of its interest, to protect its vessels against pirates, and to conduct search and rescue missions.

How to Remove Political and Legal Obstacles

Constitutionally, present German laws for expeditionary missions are still based on the supreme court’s 1994 “out-of-area decision”. According to the ruling, Germany can send troops abroad using force only in missions of international organizations (UN, NATO, EU). National missions involving the use of force abroad are forbidden, with the exception of rescuing citizens (so done in Albania 1997). Legally, Germany is not allowed to go alone for strike missions like Britain in Sierra Leone or France in Mali.Present discussions about Pooling+Sharing and German contributions to NATO capabilities (AWACS, SNMG, staff) show the limits of this legal basis. If Germany wants more NATO/EU-cooperation to work, it must change either the laws for parliamentary approval or even the constitution. Berlin is now (rightly) seen as an unreliable partner.However, right now there is a window of opportunity to change. The coming Grand Coalition has a 4/5 majority in the Bundestag. Necessary for constitution changes is a 2/3 majority. Thus, the situation for Merkel’s government is more than comfortable. Getting the Green Party to join the vote in the second house (Bundesrat) may be the tougher, but possible job.The German constitution should be changed in two ways. Firstly, it should remove present obstacles to German contributions in NATO and EU. Moreover, it should allow permanent expeditionary basing of troops, with the use of force restricted to defensive measures and saving citizens, as long as there is no international mandate for other tasks. Bundestag should get the competence to decide about expeditionary basing, either unlimited or limited in years, but with the right to bring the troops home at any time. In addition, the Bundestag has to approve the necessary funds anyway. No money, no navy.Finally, I now expect the worrywarts to challenge my case with legal and political arguments: legally difficult, politically impossible, too US-friendly and so on. However, maybe the worrywarts should start to recognize how, as outlined above, international order and German debate are changing. Time for them and for German policy-makers to adapt to a geopolitical environment, which requires Germany to do more in global and Indian Ocean affairs.