The following is an entry for the CIMSEC & Atlantic Council Fiction Contest on Autonomy and Future War. Winners will be announced 7 November.

By Hal Wilson

They were in among the Roaring Forties now. The distant horizon had melted into a gossamer gray, the sea and sky blending into some benign fug. Stampeding whitecaps roiled and tumbled, pinpricks of luminescence against the gun-metal ocean. The winds raced in mercilessly under dead slabs of cloud to deliver their brutal slap. They were the kind of westerlies the old East Indiamen vied for – all well and fine for the return journey. Less so for the southward leg.

Sub-Lieutenant Henry Dalby once hated such weather above all else. But that was before twenty days on this benighted voyage, which taught him to despise HMS Kennet with an even greater passion. It was sometime after Ascension Island that he accepted the hate billowing in his breast. He was almost ready to kill the Kennet personally.

It would be easy enough to do. She was only in the next cabin down.

It wasn’t down to the Kennet‘s sea-keeping: She handled the South Atlantic’s awe with a gambler’s nonchalance. It wasn’t down to the Kennet‘s accommodation: Carrying only fifteen crewmen but designed for forty, she seemed somehow cavernous. It wasn’t even the Kennet‘s advancing age, or its Liliputian size against the ocean wastes. (Though Dalby quailed to think a ship so small, and so far beyond his twenty-three years, was being sent so far south in a sea so vast.)

Dalby hated the Kennet because he knew she was going to kill him – unless he beat her to it. Kennet‘s Artificial Intelligence hub, the ship’s soul, filled the former officer’s cabin adjacent to Dalby’s own. The warmth of her processing power seeped through the bulkhead relentlessly. Offsetting the luxury of a cabin to himself, the sultry heat felt as if she were trying to join him, to enwrap him.

To smother him in his bunk, perhaps.

Failing that, she would kill him with the long knives of exhaustion and despair. The primitive AI operated across each of the ship’s integrated systems – an arrangement that worked acceptably in UK home waters. Thus the old hulls of the Fisheries Squadron – the Cod Squad – ran patrols and drug busts with just five officers and ten ratings, while the ship all but handled itself.

But it took three hard reboots just to reach Ascension, and the AI struggled to handle snowballing machinery problems in the ever-worsening conditions of the South Atlantic. Kennet also fostered a growing imagination. She scolded Able Seaman Carver every evening over an asthmatic condition he never possessed. She daily warned Bateson, the Chief Weapon Engineering Artificer, over illusory power surges. All hands were working flat out to keep her underway. Some doubted it would be enough.

***

Dalby ran his fingers over his scalp as he flopped onto the wardroom’s sickly-cream wall-mounted sofa. Oblivious to his dismay, a pair of black coffees steamed merrily in the nearby dispenser port.

“Two teas, Sub-Lieutenant,” Kennet crooned through monotone deckhead speakers.

Sucking air through gritted teeth, head bowed, Dalby bit down a sob. He silently checked himself, the voice in his head barbed with scorn.

Crying over coffee? Get it together. You need a safe space or something, you bloody idiot?

But where contempt broke on the armour of his fatigue, Kennet‘s caprice went clean through. After all, a mug of tea was banal enough until seen through the looking-glass of a fifteen-hour day.

Footsteps approached. Noise traveled unusually well in the ship’s sepulchral guts, despite the cheap linoleum lining every passageway. Forewarned, Dalby recovered through that ancient, unequaled power – the base need to avoid embarrassment. Able Seaman Carver appeared at the wardroom’s open doorway, knocking politely.

“What’s the matter?” Dalby said, getting to his feet.

“The Captain asked for you to hurry back, sir.” Carver’s voice was reedy and young. “All hands to muster on the bridge.” Dalby collected the coffees as he left.

“I thought he asked for tea, sir?” Carver asked, peering into the mugs.

“Don’t you start.”

***

The bridge was just large enough for the entire ship’s company. The deckhead hung low over them as they ringed a close semi-circle around their CO, Lieutenant Commander Hart. The confined space echoed to the judder–judder-judder of the bridge-window wipers. Beyond the maddening wipers, the upper deck was secured tight against the weather, safety-lines rigged, as the ship ploughed mechanically through spuming waves. Just visible from the bridge was the 76mm gun. It was locked in place, as firm as a lodestone, but the paltry calibre was as reassuring as a toy rifle.

Dalby noticed with a grimace that he and Carver seemed to be the last to arrive: There was Lieutenant Asher and the rest of the bridge team; there, the marine engineers; there, the junior technicians and even the two chefs. Shaking off the eyes boring into him, Dalby handed across a coffee to Hart.

“I asked for tea, sub,” Hart said laconically.

“My mistake, sir,” Dalby lied. “Hit the wrong button.” It was best that the commanding officer didn’t lose faith in his ship’s quality as a barista. He had precious little faith left in Kennet already.

“Listen well, company,” Hart began, setting down the coffee with polite repugnance. “Word has come in from Commander Task Force. Number One, will you do the honours?”

Lieutenant Asher stepped forth at the invitation, clearing her throat. She held a flimsy chit of paper in one hand. Her pinched, sallow face carried a grim solemnity. Dalby knew what was coming.

Judder-judder-judder babbled the mindless wipers.

“From CTF: Mount Pleasant under fire. CinC orders to break blockade regardless. RoE amended, fire on ARG contacts if fired upon. Good luck. God save the King.” Hart stepped forward.

“You know what this means. We trained for this. We volunteered for this.” He turned to Lieutenant Asher.

“Number One, I want you on Bluewatcher. Shout out if Kennet misses anything. The rest of you? Take your refreshers if you’re on watch. If you’re not – get some rest. Merlins will be here to assist with any Shayus, and I want fresh hands on standby for in-flight refuelling.” Hart paused abruptly. “Chief, what is it?”

Dalby craned his neck around – Chief Bateson had just blundered onto the bridge. Soaked from head to toe, the overweight weapons engineer gave a half-hearted, breathless salute.

“Sir, it’s the ISOs. I think the waterproofing is giving way.”

“What?” Hart hissed. “Kennet, confirm Sea Ceptor status.”

Kennet took a teasing moment to reply.

“No problems to report, Captain,” she droned, flat and lifeless.

“Sir,” Bateson interrupted, “we might be catching it early, but the contractors did a shoddy job.”

Hart could see the earnest fear in Bateson’s eyes; he trusted his engineer over his ship.

“Chief, take a gang and get aft right away. The balloon just went up at Mount Pleasant.”

“Christ. Dalby, sir. You and Carver. With me.”

“Everyone else,” Hart looked across the bridge, “dismissed.”

***

Dalby jogged to match Bateson’s surprisingly swift pace. As they rushed aft they passed the ship’s Battle Honours plaque, with Dardanelles 1915-16 and North Sea 1941 immortalised in oak. Dalby hoped they would survive to add ‘South Atlantic‘ to the modest list.

Before they emerged onto the flight deck, Bateson handed out heavy tubes of InstaFoam.

“Just point these where I tell you to,” he said tersely, dripping sea-water. “Hold the cables flush to the deck and pull the trigger-spoon. And keep your hands clear of this stuff, for God’s sake.” The trio clipped safety lines and hastily threw on their foul weather jackets, polyester chafing at their necks. With that, they bundled out. Chief Bateson had the lead.

The sea enveloped them. Lashed into fury by the punishing wind, freezing foam roared over the low freeboard and soaked them to the skin.

“This way!” bawled Bateson. Shivering already, Dalby followed.

The flight deck had been rigged with six ISO shipping containers, each twenty feet tall and speared skyward like smokestacks. Rapid welding work at Portsmouth had bound them as tightly to the deck as if they had always been there. Within each slumbered a Sea Ceptor missile, the bolt-on weapon system giving the Kennet a deadly punch. Dalby looked up. Flush over the mouth of every container was stout plastic shielding, saving the volatile missiles from corrosion.

“Sir! Do it there,” the Chief bellowed, slapping Dalby on the arm and pointing down.

Instantly, Dalby saw the problem. The fat bundles of cabling that linked each ISO to the Kennet‘s generators were coming free, rolling deferentially to the ship’s progress. One was clearly coming apart from the friction, its guts of rainbow wires open to the scourging salt. They got to work swiftly, InstaFoam spray blooming into mushroom caps of anonymous grey. The insulating material hardened instantly and pinned the cables right to the deck. For good measure, Dalby put a double spurt on the exposed length of wiring.

“That’ll have to do, you two,” Bateson shouted, pointing for them both to head back inside. Dalby let the others go first, lingering at the hatchway.

Out over the rear of the ship, the Kennet‘s wake churned fluorescence into the Atlantic’s skin.

Somewhere beyond the bland horizon skulked the escorts – the Type Twenty-Sixes and Type Forty-Fives, as vigilant as mother wolves around their cubs. The heart of their deadly affection would be the Prince of Wales and its Amphibious Task Group: the Albion and Bulwark, with their MoD-chartered RoRos; their tankers and Bay-class landing docks. Most were too old and too tired for such a journey. But between them they carried the greatest prize of all – a Brigade of Royal Marines. It was less than what their grandfathers took south with them before. It might not even be enough. But it would have to do.

Ahead of them all, groping into the Atlantic like lost, blind men, went the Cod Squad. Hart had made it clear before that CTF would not idly risk his irreplaceable F-35s and submarines. Instead these cheap, half-empty ships would be the picket for the vaunted ex-Chinese drone shoals.

Dalby paused, cocking his ear to the wind.

Thunder? He scanned the western horizon. Over there!

Distant, scudding cloudbanks were underlit by the smudge of burning iron oxide, a sick ochre glow. Against the slate aspic of the sky, that unhealthy pall could mean only one thing.

“I think that was the Avon,” Dalby announced through the hatch.

“All hands, brace, brace, brace!”

***

Dalby was a fraction of a second too slow in reaching for the nearest stanchion. He slipped, and before his lifeline could go taught, he flew headfirst into the hatch-frame with a dull thwack. His vision hazed as if his very corneas were abraded; he felt rough hands grabbing his chest to hold him down. The Kennet came about at full helm beneath him, the motion feeling as distant as the moon. Dalby’s head lolled in sympathy to it. Slowly, his vision cleared. He watched in mute fascination as a streak of phosphor fuzzed under the black waves just fifty feet away. Blinking hard, he watched it pass with all the peaceful grace of an express train, charting a path to some unseen appointment in the endless, inky Atlantic.

That was a torpedo, he mused absent-mindedly. We’re under attack.

“Get to your action stations,” Dalby groaned, struggling to his feet. “Go!” he shouted, making to move to the bridge. The two crewmen fled, hastening to their posts. Dalby tasted the tang of copper in his mouth. Ignoring it, he stumbled sternwards. Alone with his thoughts, he wondered in silent disbelief – How did the torpedo miss? We were dead to rights. Bad electronics? Poor maintenance? Dalby had read about similar problems with the enemy arsenal in the last war. The more things change…

On the bridge, the Kennet intoned flatly “Estimate target starboard bow, bearing one-nine-zero, range…”

Judder-judder-judder went the damned wipers.

Dalby glanced around. Asher was holding her left arm at an odd angle; Hart’s coffee mug tumbled freely around the deck. Hart noticed Dalby stagger in.

“Sub,” he barked. “You’re injured. Get below for treatment.”

“No, sir, I’m fine,” Dalby lied once again.

Hart himself seemed nonplussed by their close brush with death – but a shiner of a bruise already waxed purple over his cheek.

“The Kennet threw us into a sharp turn, Sub. We all got caught out. Man your post, for now.”

“A torpedo launched close to starboard,” the Kennet explained. “Emergency action was required.”

“Kennet,” Hart interrupted. “Confirm we have a Merlin en route to the target?”

“Yes, Captain. Five minutes’ flight time,” the ship answered.

“I still have it on Bluewatcher,” Asher added, teeth clenched from the pain of her broken arm. “Definitely a Shayu.”

Dalby leaned against his console, light-headed. The console’s blue panelling seemed somehow too bright, forcing him to squint. He rubbed a dribble of scarlet blood from his nose. Shayu, he recalled faintly, was Chinese for ‘Shark’. A disposable killing machine. They were autonomous little torpedo carriers, whose ubiquity grew in direct proportion to Beijing’s post-crash need for hard currency.

The saving grace about the Shayu was its noisy engine, a by-product of the cheap design. Between that and the Kennet’s cues, the Merlin helicopter was hot on the drone’s trail, readying to drop a torpedo of its own against the Shayu.

“Sir,” Lieutenant Asher warned from her sonar console, “target has changed course and increased speed. I think it heard the Merlin’s last set of sonar-buoys.”

“Lieutenant Asher is right,” chimed Kennet. “Cavitation noise increased. The Merlin crew are aware.”

Hart said nothing, arms crossed. He and his company – lacking any subsurface weapons of their own – could only watch and report. Far to starboard, the Merlin trundled above the pitching sea, splaying out rippling circles from the fierce force of its downwash. A crackle came over the radio into Asher’s headset.

“Merlin reports firm active sonar contact,” she announced, looking to the bridge windows. “It’s launching.”

Squinting, his view disturbed by the wipers’ metronome movements, Dalby watched the torpedo separate cleanly. The drop was retarded by the white flag of a small parachute. The Merlin pulled away.

Judder-judder-judder went the wipers.

The torpedo was gone. Not even a splash marked its fall. Dalby rubbed his eyes, hoping the wipers hadn’t erased the torpedo from existence.

“Merlin reports successful launch,” Kennet advised.

“Number One?” Hart asked, keen on a second opinion.

“She’s right, sir,” Asher said. “I can hear it pinging; it’s right on top of the bloody thing.”

Sure enough, the Stingray torpedo was bearing down fast on the Shayu. Even running at full speed, the drone was far too slow to escape. The surface suddenly shook white, like the spider-webbing of shattered glass. But where the Compass Rose might once have found a slain U-boats’ detritus bubbling upwards, nothing remained of the drone.

Only a single buoy surfaced, unseen and unheard, its radio bleeping word of the drone’s demise.

“It’s gone, sir,” Asher said with palpable relief. Hart nodded.

“Tell the Merlin boys good work, and we’ll go halves on the kill,” he quipped. Dalby felt the warm satisfaction of success. Or was that blood running down his neck? I need to get my head looked at, he admitted to himself.

Judder-judder-judder went the wipers.

“Be advised,” blurted the Kennet, interrupting the bridge’s blissful cheer. “Two possible surface contacts. Range 30 nautical miles. Port bow, bearing two-six-five. Possible Malvinas-class corvettes.”

***

Radar conditions were poor, but the Kennet was not wrong. It was one thing for Kennet to hunt drones. Going toe to toe with two corvettes – ships that matched the Kennet‘s tonnage and carried better armament to boot – was another thing entirely. It was damn near suicide.

The two ex-Chinese corvettes were hustling in like carrion, as if lured by the Avon’s death-fires. Their radars were powered down, to save revealing their position to the British ESM. They were listening instead to the Shayu shoals up-threat. They were a pair of matte-grey killers on the prowl. They had been waiting for this.

And now they had the fix of the dead drone’s radio beacon.

***

“Sub,” Hart snapped urgently, “did you and the Chief deal with the Sea Ceptors?”

“Yes sir. At least one of them is out of action,” he replied apologetically.

Hart cursed. The Sea Ceptors were their one real hope against these roving predators.

“Number One?” Hart looked to Asher. “We have to assume this is a positive contact. Signal Tamar and Humber – we pull back and draw the corvettes onto the fleet. Kennet? Come hard right to course three-five-zero, and give me maximum revolutions.” Everyone knew the best chance for the Cod Squad was to stay ahead of the corvettes’ grasp.

“Captain, sir. There is an alternative.” Dalby paused, brow furrowed. It was the Kennet. He had never heard the AI provide an ‘alternative’ before.

“The corvettes have almost certainly not yet detected this ship. To turn back now would fail to draw them in as you suggested.” Dalby watched, fascinated, as Hart listened. Was he the first naval officer in history to be chided by his own ship?

“Go on,” Hart growled.

“You could instead continue on the current course. You could place the radar in standby to avoid detection for now, and re-activate at closer range to act as a lure. They are attempting to ambush us; you could instead ambush them.”

Hart rubbed his temples quietly. He wanted to disagree but his ship – the bloody ship! – was right. The Cod Squad were, for now, the eyes and ears of the fleet. And AI guidance or no, he had to lead by example. Just as his father did in the last war.

“Belay my last. Tamar and Humber will withdraw to the TF outer screen. We will hold this course. Number One, update CTF.”

“Sir,” Dalby started, voice low, “Lieutenant Asher and I are injured…” he trailed off, wilting under Hart’s gaze. He didn’t want to look a coward. But he knew Asher was thinking the same – it was in her eyes.

“Do not worry, Sub-Lieutenant,” crooned the Kennet, “I can handle this myself.”

Dalby’s mouth went dry, a knot of dread in his gut. Their AI would be taking on two corvettes single-handed. And it had volunteered to do so.

***

The corvettes kept their course steadily for some time, minutes passing like the waves that foamed and fell away against their knifelike bows.

They seemed to sniff the air like vultures, hunger overcoming caution as they closed on the dead drone’s buoy. To come this far north was beyond their orders, but the Shayu shoals confirmed that lonely little ships were in the van of the British fleet. With one quick sweep they could notch some easy kills and return home heroes.

Holding a loose formation, they conferred by signal lamp. No-one wanted to risk radio this close to the British carrier. The superior of the two decided now was the time: They would be in knife-fighting range of the little ships. There was a British search radar nearby earlier – now silent – but its owner would surely make for easy pickings. If any larger escorts came chasing, they could still run with the Shayu drones to their backs – and no fool would rush a billion-pound ship into the teeth of the drones.

As if on cue, the corvettes’ radar warning receivers rang out. A rush of panic broke out for the briefest moment. The British radar shut down abruptly, as if equally shocked. The corvettes wondered – could there really be an enemy escort so close in? Have we pushed our luck too far? The lead corvette energised its radar; pulsed once, pulsed twice. There. Relief flooded the command deck: It was only one of the hapless little ships. Orders rang out to make ready for missile launch.

***

But the corvettes were being watched.

With the serene complacency of simple ignorance, they were scrutinised like bacteria under the microscope. Their albatross, hidden higher than any crossbow could ever reach, was a Fleet Air Arm F-35B. It looked and listened from behind the cloud-layer, categorising all that its sensors found, relaying hushed messages with the daring of a furtive schoolchild.

Far below, the lead corvette’s signal lamp blinked – I am attacking. Its partner acknowledged, watching expectantly like an eager sibling.

The lead ship burst apart, erupting into flames. Where one moment it sailed proudly, the next it was a mangled ruin of shattered steel and flaming fuel-oil. Cotton-wool contrails whickered skyward like a peacock’s plumage, backlit by Titian flames as the corvette died. The sister ship rocked violently, its captain reflexively ordering a hard starboard manoeuvre. But while the first missile struck a magazine, as an arrowhead spears a stag’s heart, the second lanced into the sister ship’s hangar. Barrelling into the after decks like a comet striking earth, it burrowed deep. A dud fuze saved all aboard – but it was too late for the corvette’s eviscerated engines. The ship idled to a stop, literally dead in the water.

Safe in its high castle, the albatross watched approvingly. The F-35 was blinded by cloud but his Minerva-esque sensors saw all.

“Good shooting,” judged the pilot. “One hard kill, one mission kill.” Cued up by Kennet‘s radar warnings, the F-35 had just guided two anti-ship missiles from one of the task force’s frigates. With the corvettes fixed on the Kennet‘s lure, they never saw death coming for them.

***

Hart held another chit of paper, fresh from the printer. His face split into a broad, toothy grin that Dalby found instantly infectious.

“From CTF: ‘Bravo Zulu all aboard Kennet. Drinks on me back at Pompey.’ That’s three assists in as many hours, company. You made me proud already.” Hart paused, speaking to the ship itself: “You too, Kennet. Bravo Zulu.”

“You are welcome, Captain,” the ship replied.

Dalby fancied its voice was somehow different – less monotone. Or was that the concussion talking? He cracked a smile regardless. It was April 25th: 23 days since the first war’s anniversary and the start of its sequel. But the Kennet would protect them through harder days to come. Dalby knew it.

Hal Wilson was a prior finalist in the Art of the Future Project’s contest exploring the “Third Offset Strategy” through narrative and fiction. Hal graduated in 2013 with first-class honours in War Studies and History from King’s College, London, and now works in the aerospace industry. Hal has been published by the Center for International Maritime Security, and is also launching a Cold War-themed naval-warfare board game.

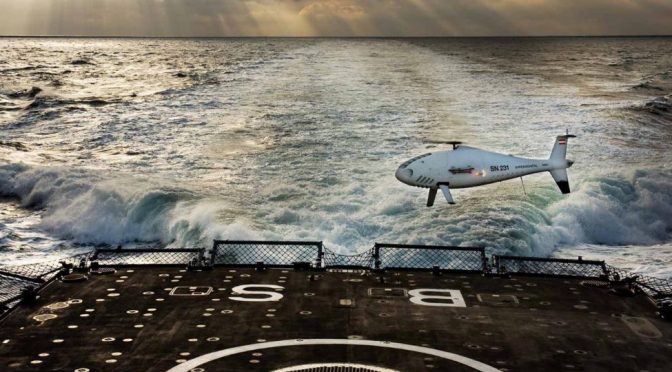

Featured Image: Flight deck crew preparing to launch the X-47B, an experimental unmanned drone aircraft, aboard the USS Theodore Rosevelt, off the coast of Virginia, Sunday, Nov. 10, 2013. (AP Photo/ Steve Helber)