Alternative Naval Force Structure Topic Week

By Chuck Hill

The Navy has been talking a lot about distributed lethality lately, and “if it floats, it fights.” There is even talk of mounting cruise missiles on Military Sealift Command (MSC) ships, even though it might compromise their primary mission. But so far there has been little or no discussion of extending this initiative to include the Coast Guard. The Navy should consider investing high-end warfighting capability in the Coast Guard to augment existing force structure and provide a force multiplier in times of conflict. A more capable Coast Guard will also be better able to defend the nation from asymmetrical threats.

Why Include the Coast Guard?

A future conflict may not be limited to a single adversary. We may be fighting another world war, against a coalition, perhaps both China and Russia, with possible side shows in Africa, the Near East, South Asia, and/or Latin America. If so, we are going to need numbers. The Navy has quality, but it does not have numbers. Count all the Navy CGs, DDGs, LCSs, PCs and PBs and other patrol boats and it totals a little over a hundred. The Coast Guard currently has over 40 patrol ships over 1,000 tons and over 110 patrol craft. The current modernization program of record will provide at least 33 large cutters, and 58 patrol craft of 353 tons, in addition to 73 patrol boats of 91 tons currently in the fleet, a total of 164 units. Very few of our allies have a fleet of similar size.

Coast Guard vessels routinely operate with U.S. Navy vessels. The ships have common equipment and their crews share common training. The U.S. Navy has no closer ally. Because of their extremely long range, cutters can operate for extended periods in remote theaters where there are few or even no underway replenishment assets. The Coast Guard also operates in places the USN does not. For example, how often do Navy surface ships go into the Arctic? The Coast Guard operates there routinely. Virtually all U.S. vessels operating with the Fourth Fleet are Coast Guard. There are also no U.S. Navy surface warships home based north of the Chesapeake Bay in the Atlantic, none between San Diego and Puget Sound in the Pacific, and none in the Gulf of Mexico with the exception of mine warfare ships.

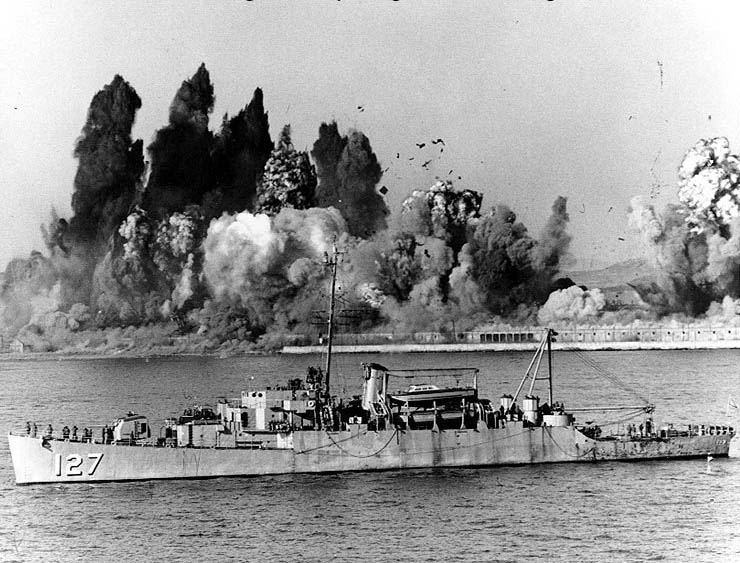

In the initial phase of a conflict, there will be a need to round-up all the adversaries’ merchant ships and keep them from doing mischief. Otherwise they might lay mines, scout for or resupply submarines, put agents ashore, or even launch cruise missiles from containers. This is not the kind of work we want DDGs doing. It is exactly the type of work appropriate for Coast Guard cutters. Coast Guard ships enjoy a relatively low profile. Unlike a Carrier Strike Group or Navy SAG, they are less likely to be tracked by an adversary.

If we fight China in ten to twenty years, the conflict will likely open with China enjoying local superiority in the Western Pacific and perhaps in the Pacific in general. If we fight both China and Russia it may be too close to call.

Coast Guard Platforms

This class of at least nine and possibly ten, 418 foot long, CODAG powered, 28 knot ships, at 4,500 tons full load, are slightly larger than Perry-class frigates. Additionally, they have a 12,000 nautical mile cruising range. As built they are already equipped with:

- Navy certified helicopter facilities and hangar space to support two H-60 helicopters,

- A 57 mm Mk110 gun,

- SPQ-9B Fire Control Radar

- Phalanx 20mm Close in Weapon System (CIWS)

- 2 SRBOC/ 2 x NULKA countermeasures chaff/rapid decoy launcher,

- AN/SLQ-32 Electronic Warfare System,

- EADS 3D TRS-16 AN/SPS-75 Air Search Radar,

- A combat system that uses Aegis Baseline 9 software,

- A Sensitive Compartmented Intelligence Facility (SCIF)

In short, they are already equipped with virtually everything needed for a missile armed combatant except the specific missile related equipment. They are in many respects superior to the Littoral Combat Ships. Adding Cooperative Engagement Capability might even allow a Mk41 equipped cutter to effectively launch Standard missiles targeted by a third party.

The ships were designed to accept 12 Mk56 VLS which launch only the Evolved Sea Sparrow missiles (ESSM). Additionally, the builder, Huntington Ingalls, has shown versions of the class equipped with eight Mk41 VLS (located between the gun and superstructure) plus eight Harpoon, and Mk32 torpedo tubes (located on the stern). Adding missiles to the existing hulls should not be too difficult.

The Mk41 VLS are more flexible in that they can accommodate cruise missiles, rocket boosted antisubmarine torpedoes (ASROC), Standard missiles, or Evolved Sea Sparrow missiles (ESSM). Using the Mk41 VLS would allow a mix of cruise missiles and ESSM with four ESSMs replacing each cruise missile, for example eight cells could contain four cruise missiles and 16 ESSM, since ESSM can be “quad packed” by placing four missiles in each cell. Development of an active homing ESSM is expected to obviate the need for illuminating radars that are required for the semi-active homing missiles. Still, simpler deck mounted launchers might actually offer some advantages, in addition to their lower installation cost, at least in peacetime.

Cutters often visit ports where the population is sensitive to a history of U.S. interference in their internal affairs. In some cases, Coast Guard cutters are welcome, while U.S. Navy ships are not. For this reason, we might want to make it easy for even a casual observer to know that the cutter is not armed with powerful offensive weapons. Deck mounted launchers can provide this assurance, in that it is immediately obvious if missile canisters are, or are not, mounted. The pictures below show potential VLS to be considered.

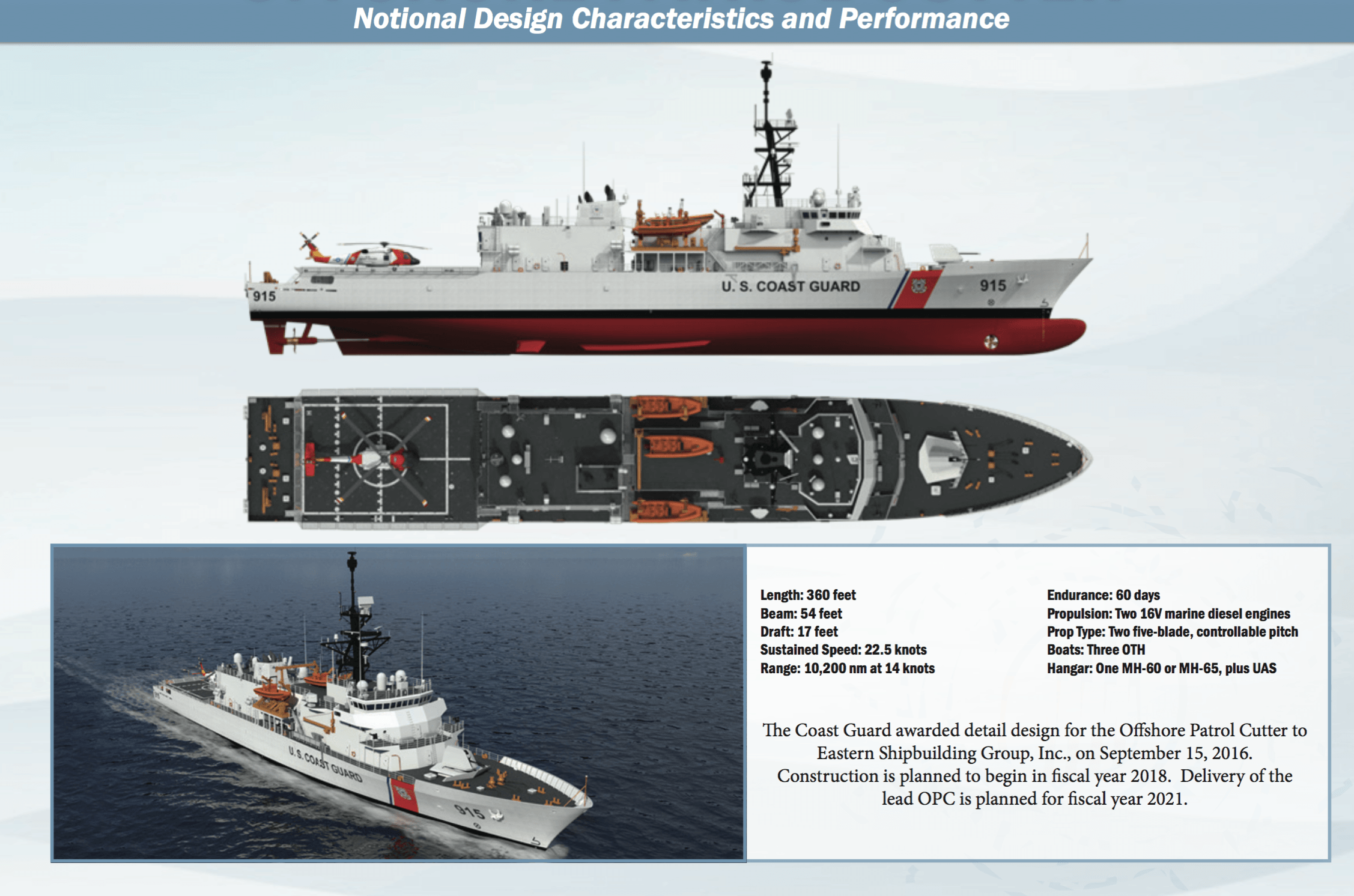

The OPC program of record provides for 25 of these ships. A contract has been awarded to Eastern Shipbuilding Group for detail design and construction of the first ship, with options for eight more. The notional design is 360 feet long, with a beam of 54 feet and a draft of 17 feet. The OPCs will have a sustained speed of 22.5 knots, a range of 10,200 nautical miles (at 14 knots), and an endurance of 60 days. Its hangar will accommodate one MH-60 or an MH-65 and an Unmanned Air System (UAS).

It will have a space for a SCIF but it is not expected to be initially installed. As built, it will have a Mk38 stabilized 25 mm gun in lieu of the Phalanx carried by the NSC. Otherwise, the Offshore Patrol Cutter will be equipped similarly to the National Security Cutter. It will likely have the same Lockheed Martin COMBATSS-21 combat management system as the LCS derived frigates. It is likely they could be fitted with cruise missiles and possibly Mk56 VLS for ESSM as well. Additionally these ships will be ice strengthened, allowing the possibility of taking surface launched cruise missiles into the Arctic.

Fast Response Cutter (FRC)

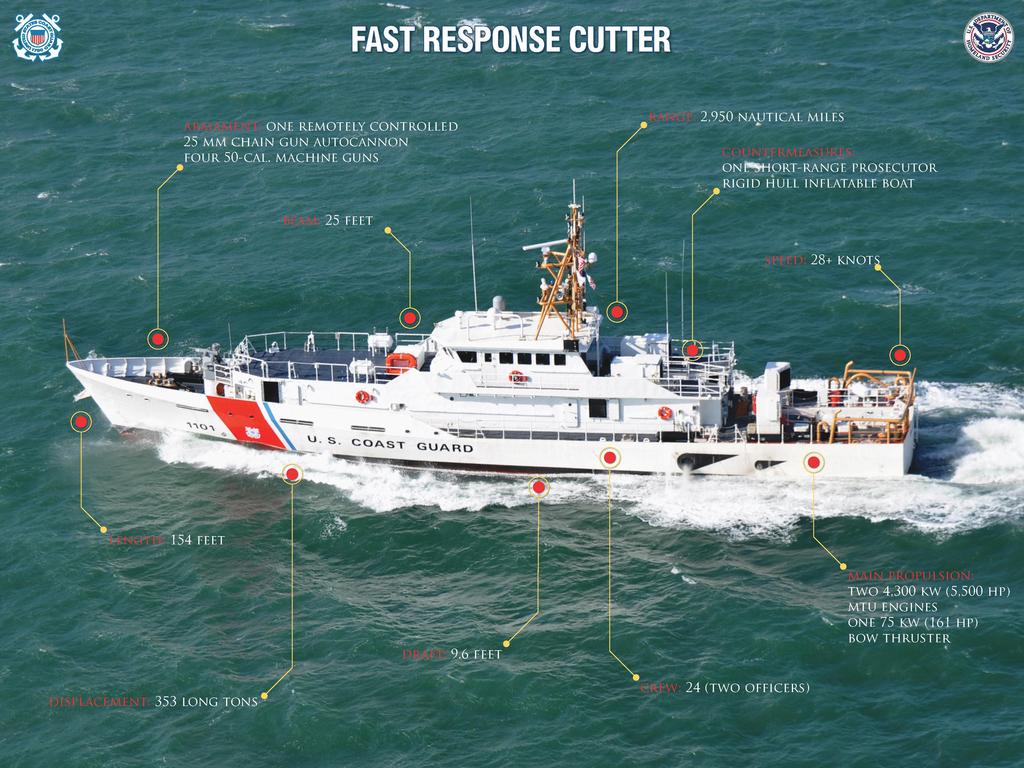

The FRC program of record is to build 58 of these 158 foot, 28 knot, 365 ton vessels. 19 have been delivered and they are being built at a rate of four to six per year. All 58 are now either built, building, contracted, or optioned. They are essentially the same displacement as the Cyclone class PCs albeit a little slower, but with better seakeeping and a longer range. Even these small ships have a range of 2,950 nm. They are armed with Mk 38 mod2 25 mm guns and four .50 caliber M2 machine guns.

They are already better equipped than the Coast Guard 82 foot patrol boats that were used for interdiction of covert coastal traffic during the Vietnam war. If they were to be used to enforce a blockade against larger vessels, they would need weapons that could forcibly stop medium to large vessels.

Marine Protector Class

There are 73 of these 87 foot, 91 ton, 26 knot patrol boats. Four were funded by the Navy and provide force protection services for submarines transiting on the surface in and out of King Bay, GA and Bangor, WA.

If use of these vessels for force protection were to be expanded to a more hostile environment, they would likely need more than the two .50 caliber M2 machine guns currently carried. The four currently assigned to force protection units are currently equipped with an additional stabilized remote weapon station.

Weapons

Cruise Missiles

The U.S. Navy currently has or is considering four different surface launched cruise missiles: Harpoon, Naval Strike Missile (NSM), Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), and Tomahawk. Of these, LRASM appears most promising for Coast Guard use. Tomahawk is the largest of the four and both Harpoon and NSM would be workable, but they do not have the range of LRASM. The intelligence and range claimed for the LRASM not only makes it deadlier in wartime, it also means only a couple of these missiles on each of the Coast Guard’s largest cutters would allow the Coast Guard’s small but widely distributed force to rapidly and effectively respond to asymmetric threats over virtually the entire U.S. coast as well as compliment the U.S. Navy’s efforts to complicate the calculus of a near-peer adversary abroad.

Small Precision Guided Weapons

It is not unlikely that Fast Response Cutters will replace the six 110 foot patrol boats currently based in Bahrain. If cutters are to be placed in an area where they face a swarming threat they will need the same types of weapons carried or planned for Navy combatants to address this threat. These might include the Sea Griffin used on Navy’s Cyclone-class PCs or Longbow Hellfires planned for the LCS.

Additionally, a small number of these missiles on Coast Guard patrol craft would enhance their ability to deal with small, fast, highly maneuverable threats along the U.S. coast and elsewhere

Light Weight Anti-Surface Torpedoes

If Coast Guard units, particularly smaller ones, were required to forcibly stop potentially hostile merchant ships for the purposes of a blockade, quarantine, embargo, etc. they would need something more than the guns currently installed.

The U.S. does not currently have a light weight anti-surface torpedo capable of targeting a ship’s propellers, but with Elon Musk building a battery factory that will double the worlds current capacity and cars that accelerate faster than Ferraris, building a modern electric small anti-surface torpedo should be easy and relatively inexpensive.

Assuming they have the same attributes of ASW torpedoes, at about 500 pounds these weapons take up relatively little space. Such a torpedo would also allow small Coast Guard units to remain relevant against a variety of threats.

Conclusion

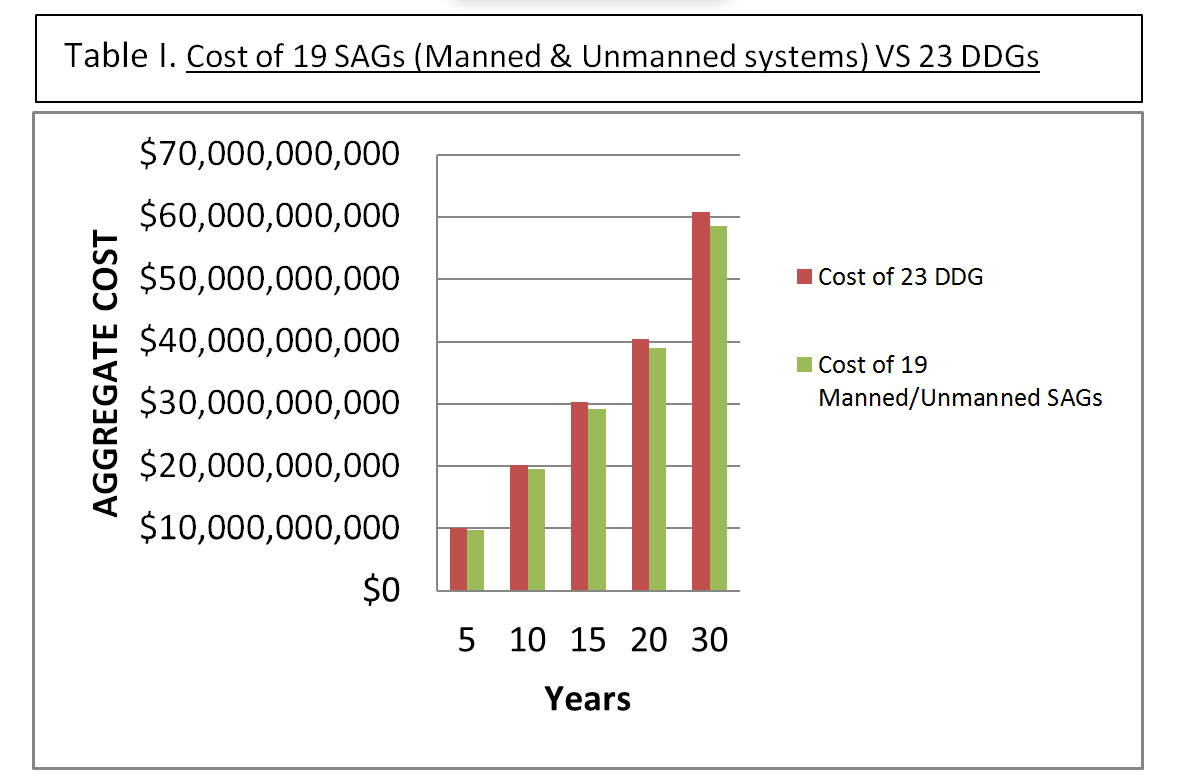

Adding cruise missiles to the Coast Guard National Security Cutters and Offshore Patrol Cutters would increase the number of cruise missile-equipped U.S .surface ships by about 40 percent.

Coast Guard Patrol craft (WPCs) and patrol boats (WPBs) significantly outnumber their Navy counterparts. They could significantly increase the capability to deal with interdiction of covert coastal traffic, act as a force multiplier in conventional conflict, and allow larger USN ships to focus on high-end threats provided they are properly equipped to deal with the threats. More effective, longer ranged, and particularly more precise weapons could also improve the Coast Guard’s ability to do its homeland security mission.

Thanks to OS2 Michael A. Milburn for starting the conversation that lead to this article.

Chuck retired from the Coast Guard after 22 years service. Assignments included four ships, Rescue Coordination Center New Orleans, CG HQ, Fleet Training Group San Diego, Naval War College, and Maritime Defense Zone Pacific/Pacific Area Ops/Readiness/Plans. Along the way he became the first Coast Guard officer to complete the Tactical Action Officer (TAO) course and also completed the Naval Control of Shipping course. He has had a life-long interest in naval ships and history. Chuck writes for his blog, Chuck Hill’s CG blog.

Featured Image: Photo: The U.S. Coast Guard high endurance cutter USCGC Mellon (WHEC-717) launching a RGM-84 Harpoon missile during tests off Oxnard, California (USA), in January 1990. by PAC Ken Freeze, USCG