This is the second article of our “Sacking of Rome” week: red-teaming the global order and learning from history.

This is not a prediction for the future, simply a thought experiment to tell a story of what might be. Thinking about how American power and influence might decline is not a slight to the United States. It is a strength. We are not a people blinded by American hubris, but instead are willing to honestly analyze the negative what-ifs while working toward the positive ones.

When discussing the fall of the United States, the initial reaction is to think of a dramatic collapse. Things such as losing World War III in an enormous battle or an economic collapse making the Great Depression look like a little setback could make for an engaging movie, but reality does not have to entertain – it simply has to be.

This is fiction, not a prediction, but hopefully it makes us think.

And Now for our Story…

The United States is powerless. Though our economy is still intact for the moment, our ability to influence events on the world stage and protect our national interests is gone. We try to turn to our allies for help, but even our oldest friends recognize that the balance of power has shifted and begin to reshape their alliances to look out for their best interests. We are alone, afraid, and powerless in a very complicated world. How did we get here?

The Age of Austerity

As the War on Terror wound down, the Department of Defense entered what has now become known as “the age of austerity.” We began to heed the warnings of Admiral Mike Mullen that our national debt is the biggest threat to our national security. It started with sequestration in 2013. The writing was on the wall that we were no longer the post-Cold War hegemon of the 1990s and once again simply a strong player within a multipolar world.

Before we knew it, China was no longer just a developing power. Profits from energy exports enabled Russia to regain its seat as a major player on the global stage. If there was a time for more guns and less butter it was then. But America was tired and mostly broke from over a decade of war, so the Department of Defense was forced to confront more diverse global challenges with fewer resources.

The future emerged amongst a sea of buzzwords and lightning bolts connecting nodes on countless PowerPoint slides within the Pentagon. It was impossible to attend a Department of Defense brief without network-centric warfare, cross-domain synergy, asymmetric advantages, and autonomous unmanned systems being heralded as the solution to all problems.

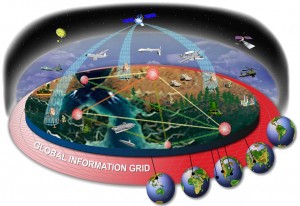

In an effort to preserve America’s military advantage while reducing long-term spending, we invested in unmanned technologies and the ability to network unmanned and highly advanced manned systems together. The network enabled coordinated operations across all domains almost simultaneously. This would provide the quick and overwhelming response necessary to defeat any adversary, and the best part was it required minimal personnel. Unmanned systems might have a high upfront cost, but they do not require a salary, medical care for dependents, or a retirement plan. The extra savings from eliminating as many people as possible enabled the establishment of a network of unmanned undersea, surface, air, and even space systems providing continuous intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance on a global scale and immediate coordinated response in the event of hostilities. The global influence of the United States was secured at a fraction of the long-term costs.

The Bubble Bursts

The American drone network continuously patrols the Air Defense Identification Zones (ADIZs) which China has established encompassing the East and South China Seas. China has made repeated complaints to the United States and the United Nations, and there have been many close calls between American assets and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy and PLA Air Force resulting in the loss of some drones, but without loss of life. Relations are tense, but the global status quo is maintained. The strategic goal of the United States is to keep economic relations with China how they currently are.

Suddenly the handful of operators within the Joint Force Drone Operations Center necessary to monitor and operate the global unmanned network find themselves staring at blank screens. What happened? An unannounced drill? A power outage? A loss this extensive has never happened before. They wonder and begin to troubleshoot.

While the casualty to the network is being reported up the chain of command, drones begin disappearing from radar screens at monitoring stations around the world. A flight of drones scheduled to land at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa for routine maintenance and refueling never arrives. Reports even begin to arrive of flights taking off and immediately crash landing. U.S. Cyber Command is alerted and begins to investigate. Once they know what to look for, it does not take long to find the malicious code responsible and it is glaringly obvious where it originated. The PLA. Not only did they not try to cover their tracks, but it looks like they wanted us to know who was responsible.

The few remaining manned platforms – a mere shadow of the previous numbers during the Cold War – are ordered to sortie toward the western Pacific in a show of force. Everyone quickly makes a devastating discovery. They are receiving no signal from the Global Positioning System. Once they are out of sight from land, ships and aircraft have no idea where they are. The Fleet attempts to adapt. They pull out the old paper charts – which they luckily retained onboard. Utilizing their mechanical compass and dead-reckoning for navigation, they set sail and attempt to find the Chinese coast.

They might not be at 100% capability, but they can at least make a show of American power with presence. Luckily, satellite communications are still functioning so they can coordinate between each other and with their operational commander. As they cross the Pacific, one by one they drop out of communications. The failures are first noticed in the radio room, but they quickly spread to ship control, combat systems, and to engineering. Every U.S. platform is now blind, impotent, and dead in the water. Within a few short days the once-feared military power of the United States is defeated without any bloodshed. Not with a bang, but a whimper.

Jason H. Chuma is a U.S. Navy submarine officer who has deployed to the U.S. 4th Fleet and U.S. 6th Fleet areas of responsibility. He is a graduate of the Citadel, holds a master’s degree from Old Dominion University, and has completed the Intermediate Command and Staff Course from the U.S. Naval War College. He can be followed on Twitter @Jason_Chuma.

The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

This week, Sea Control Asia Pacific looks at cyber security in the region.

This week, Sea Control Asia Pacific looks at cyber security in the region.