I started out the week with a few of my own thoughts and an interview with Randy Hencken, Executive Director of the Seasteading Institute, who was gracious enough to reach out and participate in our discussion.

In “From Jules Verne to Sir Julian Corbett” Viribus Unitis provided a worse-case scenario for rogue sea-based nations, and along with LT AJ Kruppa’s “Sea-based Nation Security” delved into the issues of warfare and maritime security among city-state platforms. LT Kurt Albaugh took a similar tack and pondered the potential use of sea city-states as Afloat Forward Staging Bases and launching pads for military operations in “Bridging the Moat.”

Ian Sundstrom examined the question of “Who Would Benefit Most from Seasteading?” – particularly the numbers behind the hope proposing replacing low-lying islands threatened by climate change. In “Ice-basing the Arctic,” LT Allen Tweedie questioned whether seasteads could harness the new round of excitement over trade routes and minerals in the Arctic Circle. Meanwhile, LTJG Matt Hipple imagined a future of seasteads at the forefront of mineral claim-stakers in “Seasteaders: Mining the Sea, Mining the Future.”

Exploring the source and models of sovereignty also featured prominently in CDR Doyle Hodge’s “Sea-based Nations and Sovereignty,” Matt Hipple’s “SeaUnsteady: Personal Sovereignty” and Susanne Tempelhof’s “Why the U.S. Should Embrace Seasteading.” This segued into discussions on the nature of citizenship and government in the last two articles –where seasteaders particularly hope to inspire new lines of thinking.

A few final thoughts:

International Law:

One common issue posters grappled with was the applicability of international law to the concept of seasteads. As it stands, international law in the form of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) throws up many road blocks for seasteads and sea-based nations.

Ian Sundstrom pointed out that UNCLOS doesn’t grant man-made structures their own EEZs, reducing the resource incentives for a seastead to transition from a flagged vessel to a micro-nation; LTJG Hipple noted UNCLOS has established rules for the mining the deep-sea bed in international waters; and, multiple posters discussed both the necessity of flagging a seastead as a vessel (if only for their own protection) and the restrictive effects of existing states’ territorial waters, contingency zones, and EEZs on placing a new sea-based nation.

All this illustrates the importance and real impact international law can have on maritime security and the health of a nation’s economy. It also suggests the benefits to be gained by influencing international law to one’s own advantage – as Randy Henrickson himself pointed out. This is something done through enforcement of international customary law, for example freedom of navigation transits through international straits, or by having a seat at the table when negotiating the terms of treaties or helping to enforce, interpret, or implement them. True, a nation (even a sea-based nation) can violate the rules, but there are courts and international mechanisms which can make it very painful on the pocket-book to do so (whether or not a signatory), through negative trade rulings, banking sanctions, or exclusion from certain markets. In short, those hoping to seastead or create a sea-based nation have a lot of work to do not only in creating new experiments in government, but in changing or gaining acceptance for new international norms.

Flagging:

The preferable flag for seasteads will vary based both on their location and their future intent. Those seeking to eventually declare themselves a fully fledged micro-nation would do well to choose a flag of convenience. While flags of convenience provide only the bare minimum of legal security against other states and criminal enterprise, they do promise minimal interference both in the short-term and the day when a seastead attempts to gain acceptance as a micro-state. The navies and coercive powers of Panama and Liberia are, sorry to say, not particularly fearsome. Additionally, the lack of security provisions of the flag state can be balanced by recourse to the legal systems (and militaries) of the seatead’s own citizens – at least until they become members of their new micro-nation.

For those seeking to create a seastead near the EEZ of another nation, there are a couple options, each with its own advantage, if autonomy short of independence is acceptable. First, the seastead could seek the flag of the major port – this would greatly lower the cost of doing business with what will likely be the seastead’s major trading partner and critical logistical support hub. Second, the seastead could seek the flag of a “champion powerful enough to coerce non-interference,” as CDR Hodges put it. This could be a nation looking for a major trading hub, a nation looking for a military foothold in the region, or some combination of the two.

Sovereignty and Resources:

No matter what route seasteads take to attempt the transition to micro-nations or harness the resources of international waters, the difficulties they will face are daunting – but not insurmountable.

A clear mechanism for the transition to micro-nation would be preferable. Perhaps with minimum qualifications such as self-sufficiency, a written constitution, a minimum population level (and a hefty “application fee”). Whether or not the sea-based nation was mobile would also factor in, with a permanent residence likely gaining greater acceptance. A successful qualification could be awarded territorial waters an EEZ, and a zone in which it can mine the deep sea bed. These distances could be specifically delineated on a case-by-case just as the 200nm EEZ was created out of whole cloth. A sea-based micro-nation could be its own form of sovereignty with its own legal conditions rooted in international law. Here I turn the question to you – what other sorts of qualifications do you think should be applied?

In reality we are likely to see more muddled development, with some seasteads gaining recognition by one set of nations, and others another. The aforementioned powerful champions will likely aid those with cultural ties, hold out the promise of co-developing resources, or offer a military or economic foothold as described above – presenting seasteads with the trick of charting their course to true sovereignty in a sea full of sharks (but such is the case of diplomacy everywhere).

Security:

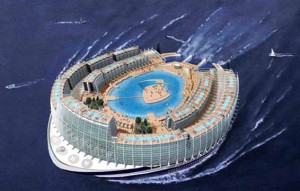

Lastly, seasteads may also experiment with what are really old models of armed forces, by requiring all hands or all citizens to be ready to defend themselves against attack (see picture), they may require new citizens to spend a spell in dedication to the nation (universal conscription), or they may just hire out mercenaries. The size, economic-base, wealth, technological level, form of government, and relative security will all play a role in determining the form of the armed forces.

It’s also important to remember that not every seastead or sea-based nation will be floating, but many will, and that will make them particularly vulnerable to any sort of attack. The morality of bombing/torpedoing such a target might be equated to sinking dual-use ocean liners and might force the type of hybrid maritime/urban warfare Viribus Unitis discussed – especially if the sea-based nation develops few offensive or stand-off weapons to justify an initial bombardment.

We may hear more about sea-based nations in the future, with another interview or two in the works. And for those of you in the DC area, don’t forget our meet-up Wednesday, from 6-10pm at District Pi Pizza, where you’ll have a chance to meet a few of the posters and discuss in person the writing. We’ll also have an informal poll from the week for the Best Written, Most Original Thought, and Most Persuasive pieces.