By Rachel Gosnell

Introduction

The economic potential of the Arctic is vast, but the complexities of the region must be considered when analyzing the future of the Arctic. While the region north of the Arctic Circle is commonly viewed as a singular expanse, the reality is rather different. Within the Arctic – and amongst the eight Arctic nations – there exists noteworthy similarities but also tremendous variations. Indeed, the Arctic is a diverse part of the world that would be best characterized as several different subregions, all with unique resources, populations, accessibility, geostrategic importance, and challenges. It is critical to analyze economic drivers and political factors across the High North in order to evaluate the economic potential of the region, understand national security interests, and develop appropriate Arctic policy.

A Challenging Environment

One constant throughout the Arctic region is the hostile climate. Record setting cold, ice-covered waters, rapidly emerging storms, and high winds define the region. The warming trends of the High North, which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) note are about double the rate of global warming trends, are of such a magnitude that the pace of sea ice decline and surface ocean warming is unprecedented. This warming is contributing to an alarming decline in ice coverage at sea and permafrost ashore. The warming trends are forecasted to continue at an increasingly rapid rate due to the albedo effect, making Arctic weather more unpredictable as the likelihood of fog, storms, and even ice floes rises in upcoming years. All Arctic states must confront these challenges and share a common interest in conducting research to better understand the scientific trends that are emerging in the region.

The majority – nearly half – of the Arctic’s four million inhabitants live in the Russian Arctic, with the largest communities located in Murmansk and Norilsk. These cities dwarf the largest comparable North American communities, though population trends indicate a slight shift toward growth in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic. Yet the Arctic population in total is predicted to experience only a slight upward growth in the upcoming decades, with just a 4 percent growth rate predicted through 2030. When compared with the global growth rate projection of 29 percent over the same period, it becomes clear that the region will not becoming a booming source of labor. Indeed, the Business Index North 2018 report notes that many cities in the Arctic are confronting challenges stemming from the loss of the region’s youth – who move south in search of education and jobs – and a gender imbalance. Further, as the Arctic warms, attracting interest to the region, the indigenous communities are facing new challenges. Thawing permafrost is causing damages to infrastructure as the ground becomes less stable. Developing new infrastructure to support economic development will require innovative approaches in a region not experienced in such issues. The logistical difficulties of transporting building materials and expertise will further compound the issue.

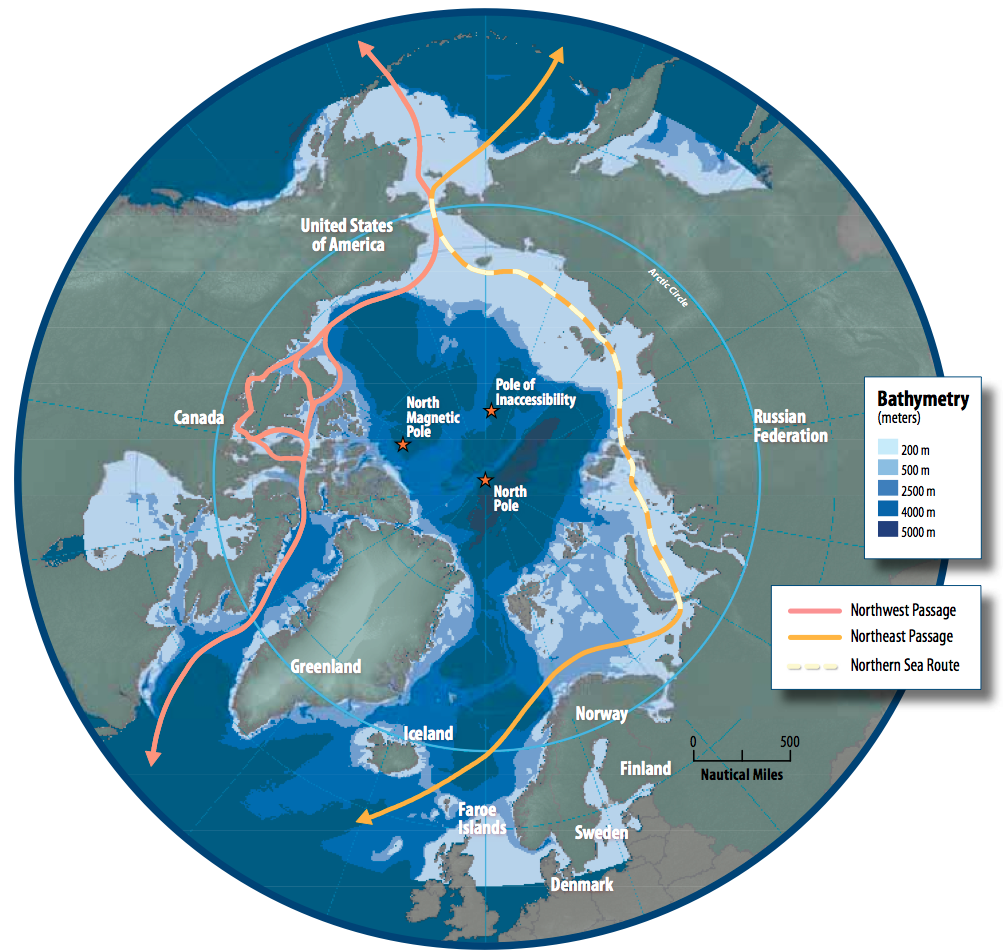

The warming trends, however, will certainly enable further economic activity in the region. Diminishing sea ice coverage is enabling greater maritime traffic. However, it remains unlikely that the northern routes will become competitors of the Suez Canal despite the difference and significantly shorter distance (approximately 4,700nm) from Northern Europe to East Asia that amounts to a decreased transit time of 12 to 15 days if weather conditions cooperate. Yet of the primary identified shipping routes through the Arctic – the Northern Sea Route (NSR), Northwest Passage (NWP), and Transpolar Route (TPR) – only the NSR will have extended periods of opening through approximately 2025.

New Opportunities

Shipping companies and countries alike are exploring the potential new trade routes. Putin has exclaimed that the Northern Sea Route will rival international trade lanes and indeed, there has been an increase of vessel activity in the region. In 2017, the Northern Sea Route Administration (NSRA) issued 662 permissions to vessels for navigation along the NSR, though only 107 of these for foreign (non-Russian) flagged vessels. During that year, the NSRA notes that 9.74 million tons of various freights were transported by vessels, though mostly between ports located along the NSR. Indeed, in 2017, there were only 24 vessels and 194,364 tons of cargo that transited the duration of the route – much less than the record high in 2013 when China’s COSCO and others sent cargos through to explore the possibility of a maritime route. That year, aided by exceptional weather conditions, 71 vessels and 1.36 million tons of cargo transited the Northern Sea Route. Yet this still pales in comparison to the Suez Canal traffic, which saw more than 17,600 vessels and 1.04 billion tons of cargo in 2017.

Weather and vessel size limitations – due to reduced water depths and widths limited to icebreaker accompaniment – will reduce the efficiencies of the commercial shipping industry, which values economies of scale and the just-in-time shipping model. Arctic shipping in its current state is not yet reliable enough to adhere to these requirements, although when the Transpolar Route opens it may become more appealing. China has already looked northward to link the “Polar Silk Road” to its broader One Belt One Road Initiative. Yet weather will remain a challenge, with unpredictable ice floes moving into vessel routes, harsh storms, and cold operating temperatures. The International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code was a solid effort to improve safety and establish training and operating standards for vessels in the Arctic, but it will likely need continuous updates to remain relevant. International coordination on Arctic maritime safety and emergency response will be critical to ensuring the prevention – or expeditious response – of a maritime crisis. Given the fragility of the environment, hostile conditions, and dearth of emergency response capabilities in the Arctic, cooperation will be critical to the future.

Another significant economic driver for the region is the abundant presence of energy both on shore and within the exclusive economic zones of the five Arctic coastal nations. Several countries have already submitted claims to further extend their claims under the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. This includes a number of overlapping claims, to include the Lomonosov Ridge – and the North Pole. Although the United States remains the sole Arctic nation that has not ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) it appears that all Arctic nations will submit claims in accordance with UNCLOS. Yet the review of such claims make well take years due to the backlog of the Commission and the complexity of the review process. Until then, there remains a potential for disputes over economic resources, although Norway and Russia resolved the biggest dispute in the region peacefully in 2010. Currently the largest disputes in the Arctic are between the United States and Canada.

While oil and gas reserves are still unknown, it is estimated that the Arctic may hold nearly one-third of the world’s natural gas and thirteen percent of global oil reserves. Yet costs of exploring, developing, and extracting these resources are very high given the harsh environment, limited infrastructure, and difficulties posed. Given the current market prices, there is limited interest in pursuing these reserves in North America, though Norway and Russia are continuing development in the Barents and Kara Seas. The Chinese Nanhai-8 rig made an April 2018 discovery that may rank the Leningradskoye field as one of Russia’s largest natural gas fields. Indeed, China has also invested in the Yamal LNG project, which has ownership of 50.1 percent by Novatek, 20 percent by total, 20 percent by China National petroleum Company, and 9.9 percent by the Chinese Silk Road Fund. Production officially began in December 2017 and officials predict an annual production of up to 360 billion cubic meters of gas. The new Christophe de Margerie class of icebreaking LNG carriers – projected to be a total of 15 vessels at more than $300 million apiece – has commenced deliveries from Yamal to Asia. While the transit shipping of cargo may not be viable for decades, it is clear that Russia is intent on using the Northern Sea Route to ship commodities to market, albeit on a small scale when compared to the global maritime industry. Overall production of Arctic energy reserves will likely remain limited in the near future, unless the price of oil climbs significantly. Other sources of oil and gas – to include shale and using newer technology on older fields – will continue to remain a more economical option.

Mineral resources are also found in vast quantities throughout the Arctic, with all Arctic nations except Iceland possessing significant mineral deposits. While some new deposits are being revealed as ice coverage melts, it is likely that development in the near term will continue to focus on existing mines. It is predicted that infrastructure to these mines and areas will steadily be improved to permit future access.

Changes in climate are also likely to result in increased fishing in the Arctic. While there is little data on exact sizes of Arctic fishing stocks, it is likely that fish will continue migrations northward as the waters warm in the south. International fishing fleets will follow these fish, and the level of illegal and unreported fishing will likely rise due to the challenges of monitoring the vast region and lack of comprehensive maritime domain awareness. Yet this is also another opportunity for the Arctic coastal states to work together, in regulating and monitoring fishing. Likewise, the regulation of tourism in Arctic water – and the establishment of clear safety and emergency response protocols – will require cooperation from the Arctic states as the numbers of tourists rise. Indeed, the 2016 and 2017 Northwest Passage transits of the Crystal Serenity cruise ship and 1,800 passengers (900 guests) highlight the importance of developing both regulations and crisis response procedures as the adventure tourism industry continues to grow.

A final economic factor in the Arctic will be foreign direct investment. To date, the Arctic has received significant levels of FDI, with China being the largest source at an estimated $1.4 trillion invested into the economies of the Arctic nations from 2005-2017. Concerns arise over the potential for externalities associated with this investment, particularly given China’s record on labor and environmental issues. China’s recent Arctic White Paper establishes that China will continue to seek investment and other economic opportunities in the region.

Conclusion

The Arctic is brimming with economic potential. Though the population will continue to be a small fraction of the global population, the region has significant natural resources and potential as a maritime trade route. With an annual economy presently exceeding $450 billion, it is likely that the region will experience further growth as the Arctic becomes increasingly accessible. Yet Arctic states must carefully regulate this growth in order to ensure protection of the environment, indigenous peoples, and their own strategic interests. This will further require significant cooperation amongst the nations of the High North – and those with interests in the region – in order to ensure the development and adherence to protocols and regulations that guide economic development.

Rachael Gosnell is pursuing doctoral studies in International Security and Economic Policy at the University of Maryland, with a focus on maritime security in the Arctic. She holds a MA in International Security Studies from Georgetown University, a Masters in Engineering Management from Old Dominion University, and a Bachelors of Science in Political Science from the U.S. Naval Academy. She currently teaches Political Science at the U.S. Naval Academy. All views expressed are her own and do not reflect the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Naval Academy.

Featured Image: Helicopter view of U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy (bottom left) stopped in the Arctic Ocean as Canadian Coast Guard Ship Louis S. St. Laurent (top right) comes alongside it. (Jessica K. Robertson/Public Domain)