By David R. Strachan

Events of the past decade have forced the United States Navy to re-imagine undersea warfare in light of two emerging and interrelated trends: the rise of sophisticated unmanned undersea systems, and a dramatic increase in geopolitical tensions suggesting the return to an era of near-peer competition and great power conflict. Russian activities in the Crimea, Middle East, and the Arctic, as well as China’s growing regional influence in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean are prompting the Navy to shift its priorities from confronting lesser threats such as rogue states and nonstate actors, and being a “global force for good,” to planning and preparing for the possibility of large-scale warfare against a well-equipped, modern navy. As such, warfighting concepts and operations mothballed after the Cold War are now in need of urgent re-tooling for the current era.1

One such operation experiencing a kind of renaissance is mine warfare which, when combined with unmanned technologies and key infrastructure based on the ocean floor, transforms into the more potent strategic tool of seabed warfare. But even the concept of seabed warfare is itself in transition, and is on track to be fully subsumed by the broader paradigm of autonomous undersea warfare. Mines and associated sensors, as currently employed, will be a thing of the past as their functionality is absorbed by fleets of smart, mobile, autonomous vehicles. More profound still will be the range of new threats unleashed by autonomous undersea warfare. The U.S. Navy must anticipate these threats and recognize that its continued dominance of the undersea domain will rest on its ability to prepare for the kind of combat the coming era of unmanned undersea conflict will entail.

Not Your Father’s Seabed

Warfare conducted on and from the ocean floor is nothing new. For the better part of a century, ships, aircraft, and submarines laid mines and encapsulated torpedos fitted with an array of magnetic, acoustic, and pressure sensors. SOSUS provided valuable intelligence on Soviet naval activities, and during the 1970s, U.S. spy submarines successfully tapped Soviet undersea cables, resulting in what is arguably one of the greatest intelligence coups of the Cold War. But while conceptually seabed warfare may not be new, it is evolving, and is poised to be more fully developed and integrated into the wider grid of unmanned maritime operations.

The U.S. Navy and DARPA have anticipated this evolution, and have proposed a variety of operating concepts to prepare for it, namely:

- Advanced Undersea Warfare System (AUWS) – A distributed network of remotely controlled unmanned systems that can be rapidly deployed and custom configured for battlespace shaping and A2/AD. 2

- Forward Deployed Energy and Communications Outpost (FDECO) – An array of fixed undersea docking stations providing recharging, communications, and data transfer to extend UUV reach and endurance.

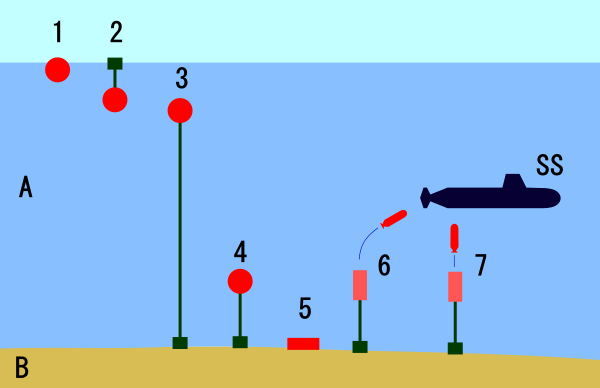

- Modular Undersea Effectors System (MUSE) – A system of fixed, encapsulated payloads capable of deploying weapons, decoys, communications nodes, and other such “effectors.”3

- Hydra – A DARPA-led initiative that calls for a distributed undersea network of unmanned payloads and platforms “trucked in” and deployed from large UUVs.

- Upward Falling Payloads (UFP) – Similar to MUSE, this DARPA initiative proposes fixed, self-contained payloads on the seabed for remote activation and deployment.

The future state of seabed warfare lies somewhere in the integration of these five operational concepts. Appropriately, each one showcases the dominant role of unmanned, autonomous or semi-autonomous systems that are tightly networked to both manned and unmanned assets operating above, on, and below the sea. But they also rely heavily on the deployment of fixed seabed infrastructure, specialized hardware that may be required in the near-term, but will present logistical challenges and also leave critical systems vulnerable to attack. We should expect that in the opening days, if not hours, of a war with Russia or China, seabed systems will be at the top of the target list. Therefore, while this configuration may work for coastal defense of the United States and our allies, its cumbersome and resource intensive nature will only add a layer of operational complexity that could compromise readiness in a forward deployed environment.

Nipping at Our Heels

Our adversaries are not standing still, and are inching ever closer to technological parity with the United States in both unmanned undersea systems and seabed warfare. Both Russia and China maintain robust search and development programs that have resulted in impressive gains over the past few years alone.

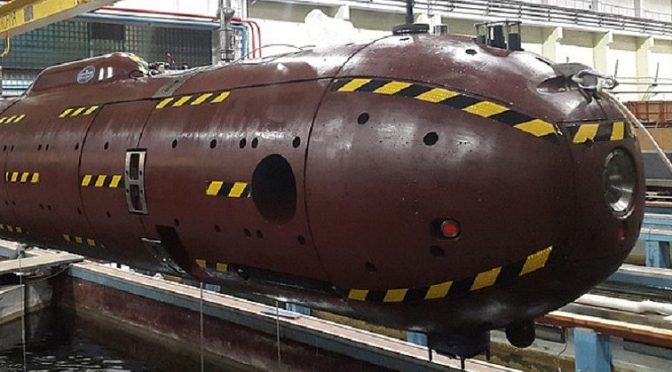

Since 2007, Russia has made great strides in undersea warfare, deploying several new classes of submarines, and conducting deep sea operations on the floor of the Arctic Ocean, and has made no secret of its intention to build a robust undersea capability to offset the asymmetric advantage of the United States. Among some of Russia’s more impressive initiatives include:

- Project 09852 Belgorod – At 600 feet, this modified Oscar II-class is the largest nuclear submarine ever built. It is designed to operate on or near the Arctic seabed, and deploy an array of unmanned vehicles, manned submersibles, and other systems, “including ones that do not yet exist.”4

- Oceanic Multipurpose System Status-6 – An intercontinental nuclear powered autonomous torpedo, purportedly capable of speeds of up to 100 knots and a running depth of 1000 meters, this doomsday weapon is armed with a 100 megaton “salted cobalt” warhead capable of destroying ports and naval installations and rendering the area uninhabitable for decades.

- Harmony – A SOSUS-style network of bottom sensors placed on the floor Arctic Ocean and powered by small nuclear reactors.5

- Project 09851 Khabarovsk – A submarine designed ostensibly as a deployment platform for Status-6.6

Russian submarines have also been observed near undersea cables in the North Atlantic, prompting speculation that Moscow is either exploiting or interfering with global information flows, or preparing for the possibility of severing critical information infrastructure in the event of war.

China, on the other hand, seems content, at least publicly, to assume a more defensive posture and focus on establishing a wide network of fixed and mobile sensors in the South China Sea. Chinese vessels have been aggressively mapping the seabed and gathering oceanographic data for scientific and military applications. Last summer, a dozen Haiyi undersea gliders were released into the South China Sea, reaching record depths while transmitting data in real-time to land-based laboratories, suggesting a breakthrough in undersea communications.7 And China State Shipbuilding Corporation has put forth a concept it calls the “Great Undersea Wall,” a distributed network of air, surface, and subsurface sensors to identify and track submarines in the South China Sea.8 A three dimensional model of the project featured an array of sensors, UUV docking stations, and undersea cables, very similar to FDECO.9 While publicly China’s seabed warfare efforts appear to be mirroring those of the United States, given the breathtaking extent of China’s activities in the Spratly Islands, we can only speculate as to what may be occurring on the ocean floor, and whether it moves beyond benign surveillance to something more lethal.

What do these developments by our potential adversaries mean for the United States Navy? Clearly both Russia and China are achieving significant technological milestones that should concern if not alarm Navy leaders. As such, we are reaching a point where it may not be enough to deploy passive, defensive systems that do little more than blunt offensive capabilities. The Navy is, at the end of the day, a fighting force, and it should be prepared to fight, and the fight may be soon happening on or near the seabed.

Preparing for a New Kind Of Conflict

Numerous seabed and UUV programs are currently under development or deployed to the Fleet. Given that we are still very much in the infancy of unmanned undersea warfare, this should be expected and encouraged. The Navy should indeed cast a wide net in an effort to understand the potential and the limits of unmanned systems. However, while “letting all the flowers grow” has its merits, the time for greater clarity in roles and expectations for these systems is here, particularly as advancements in adversary programs continue unabated.10

While any AUV program should integrate a full spectrum of effectors, it is critical that it also be capable of intercepting enemy unmanned vehicles and striking enemy seabed infrastructure. To date, however, the development of unmanned undersea craft has been driven by non-combat requirements – oceanographic research, intelligence gathering, mine countermeasures and other roles deemed too dangerous or tedious for human involvement. Other than passing references to anti-UUV operations, little has been written regarding the potential for equipping unmanned undersea vehicles for combat or strike operations. This may be due to the infancy of the technology, or ethical considerations surrounding autonomy, or that it smacks too much of science fiction, but it may also be due to the fact that actual undersea combat (i.e. submersible vs. submersible, submersible vs. seabed target) has been largely nonexistent, and in fact has only resulted in one kill in the history of submarine warfare.11 Since World War II, undersea warfare has been more a high-stakes game of cat and mouse, to deliver cruise missile attacks, gather intelligence, and maintain a viable nuclear deterrent.

But whereas in peacetime there is every reason to avoid confrontations between manned platforms, such reasoning may not necessarily hold in the case of unmanned systems. Unencumbered by this imperative, and with the cover of the opaque undersea environment, as well as plausible deniability to cloak them, fleets of unmanned vehicles will be free to disrupt, degrade, and destroy seabed infrastructure – and one another – at will.

As such, the Navy should move to develop a single, highly modular class of autonomous undersea vehicle that operates in “Strikepods,” adaptive, autonomous undersea strike groups comprised of any number of vehicles, and designed to execute missions of varying scale and complexity, such as ASW, ISR, MCM, and EMW, but also, importantly, counter-AUV and time-critical strike. Deployed from shore, surface ships, aerial assets, or submarines, and operating either within the water column or on the seabed, they would effectively eliminate the need for cumbersome, costly, and vulnerable fixed infrastructure on the sea floor.

Given its highly modular design, each vehicle would be capable of performing the role of any effector, from sensor to communications node to weapon, whether mobile, hovering, or fixed on the seabed, and ideally would be capable of dynamically reconfiguring at a moment’s notice to compensate for losses or malfunctions and ensure mission success. Strikepods could clandestinely penetrate the A2/AD defenses of an adversary and then deploy to the seabed as fixed bottom sensors, or EMW nodes, or could await further orders and dynamically activate as a bottom mines, or CAPTOR-style mines to attack enemy submarines or surface ships. In a combat role, Strikepods could be programmed to swarm and attack enemy submarines or surface ships, seek and destroy enemy unmanned vehicles, or attack enemy seabed infrastructure.

Autonomous undersea combat vehicles represent a logical progression in the emerging era of undersea warfare, a fact that will not be lost on our adversaries. They too will one day be capable of deploying AUVs in a covert, standoff manner, and operating within our territorial waters and inland waterways with impunity. Moreover, their low cost and eventual proliferation could enable rogue states and nonstate actors to acquire their own “poor man’s navy” and threaten U.S. forces at home or abroad. Thus, the need for a coastal undersea defense network will be vital to counter this threat. For example, an “Atlantic Undersea Defense Network” (AUDEN) would be a regional tactical grid comprised of numerous Strikepods deployed along the coast near ports, chokepoints, naval installations, and critical infrastructure. AUDEN Strikepods would operate both within the water column and on the seabed to deter incursions of adversary AUVs, and, if necessary, detect and engage them.

Conclusion

As the world undergoes a shift toward near-peer competition, the U.S. Navy must reexamine its role as a fighting force in light of unmanned undersea systems, and the aspirations of ever more technologically sophisticated adversaries. Seabed warfare in particular, understood as a combination of “old school” mine warfare with advanced technologies, is evolving rapidly, and is poised to be more fully developed and integrated into the new paradigm of autonomous undersea warfare. The Navy’s continued undersea dominance will rest on its ability to master seabed warfare, and to anticipate and prepare for the kind of challenges, threats, and opportunities autonomous undersea conflict will present. It will no longer be enough for the Navy to simply out-fight its adversaries. In the era of autonomous conflict, it will have to out-innovate them.

David R. Strachan is a naval analyst and writer living in Silver Spring, MD. His website, Strikepod Systems (strikepod.com), explores the emergence of unmanned undersea warfare via real-time speculative fiction. He can be reached at [email protected].

Endnotes

[1] Dmitry Filipoff, “The Navy’s New Fleet Problem Experiments and Stunning Revelations of Military Failure,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), March 5, 2018. https://cimsec.org/the-navys-new-fleet-problem-experiments-and-stunning-revelations-of-military-failure/35626

[2] See: Dave Everhart, “MINWARA Technical Session I, Advanced Undersea Weapons System (AUWS) [PowerPoint presentation], May 8, 2012. https://cle.nps.edu/access/content/group/3edf6e90-24e8-4c31-bffd-0ee5fb3581a6/public/presentations/Tues%20pm%20A/1330%20Everhart%20AUWS.pdf, Scott D. Burleson, David E. Everhart, Ronald E. Swart, and Scott C. Truver, “The Advanced Undersea Weapon System: On the Cusp of a Naval Warfare Transformation,” Naval Engineers Journal, March 2012. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/asne/nej/2012/00000124/00000001/art00010;jsessionid=76tt4k2q2j7d9.x-ic-live-02, Joshua J. Edwards and Captain Dennis M. Gallagher, USN, “Mine and Undersea Warfare for the Future,” Proceedings Magazine, August, 2014. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-08/mine-and-undersea-warfare-future

[3] Scott Truver, “Naval Mines and Mining: Innovating in the Face of Benign Neglect,” Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), December 20, 2016. https://cimsec.org/naval-mines-mining-innovating-face-benign-neglect/30165

[4] David Hambling, “Why Russia is sending robotic submarines to the Arctic,” BBC, November 21, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20171121-why-russia-is-sending-robotic-submarines-to-the-arctic

[5] HI Sutton, “’Harmony’ submarine detection network, Covert Shores, November 12, 2017. http://www.hisutton.com/Spy%20Subs%20-Project%2009852%20Belgorod.html

[6] Ibid.

[7] Stephen Chen, “Why Beijing is Speeding Up Underwater Drone Tests in the South China Sea”, South China Morning Post, July 26, 2017. http://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2103941/why-beijing-speeding-underwater-drone-tests-south-china

[8] Catherine Wong, “’Underwater Great Wall:’ Chinese firm proposes building network of submarine detectors to boost nations defence,” South China Morning Post, May 19, 2016. http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/1947212/underwater-great-wall-chinese-firm-proposes-building

[9] Jeffrey Lin and P.W. Singer, “The Great Underwater Wall of Robots: Chinese Exhibit Shows Off Sea Drones,” Popular Science, June 22, 2016. https://www.popsci.com/great-underwater-wall-robots-chinese-exhibit-shows-off-sea-drones

[10] Testimony of Bryan Clark, House Committee on Armed Services, Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces, Game Changers – Undersea Warfare, 114th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 7, October 27, 2015. https://armedservices.house.gov/legislation/hearings/game-changers-undersea-warfare

[11] Sebastien Roblin, “The True Story of the Only Underwater Submarine Battle Ever,” The National Interest, November 18, 2017. http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/the-true-story-the-only-underwater-submarine-battle-ever-23253

Featured Image: Russian Harpsichord-2P-PM (via Hisutton.com)