Distributed Maritime Operations Topic Week

By Kevin Eyer and Steve McJessy

Origins and Implications

While the concept of Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) may represent the major, new thrust in the Navy’s warfighting thought, it does not arrive out of a vacuum. In order to fully understand both the concept and implications of DMO, it is essential to first understand the seminal documents and thoughts out of which it grew.

The kernel ideas as to what DMO might one day become has existed in Navy circles for some time, and these have grown organically along with certain elemental technological steps. The first of these steps began with the advent of a significant Soviet threat arising with the fielding of a major anti-ship cruise missiles capability in the late 1950s. In response, the Navy undertook two significant programs; a shift in defensive primacy from guns to missiles, and; the development of Tactical Data Links (TDL). Missiles provided the necessary speed and reach, and “TADILs” were designed to share each connected unit’s radar picture among all TADIL capable units in the local force. For the first time forces were knit together by more than flashing light, signal flag, and radio communications.

The second major event was the development of the Aegis Combat System (ACS), which began in the mid-1960s and came to fruition in the late 1970s. It is generally understood that with the advent of the ACS, ships achieved a near full integration of the disparate, elemental combat systems in those ships. Everything in an Aegis ship’s combat systems was suddenly able to work together, synergistically.

The last step necessary in moving from non-integration at any level to full integration of a force occurred with the Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC), which came out of “the black” in the early 1990s. In a nutshell, CEC operates in a fundamentally different manner than do classic data links. Unlike TDLs, rather than sharing only highly processed symbology in a time-late and low granularity manner, CEC shares raw sensor data directly off a sensor’s buffers, unprocessed, and with such speed and volume that it appears to each every participating unit as if any netted sensor is an actual element of every other unit’s own Combat Management System (CMS). With CEC, an identical, real time, fire-control quality picture of the surrounding battlespace is resolved in every connected unit. Before CEC, an Aegis ship could only engage a threat once that threat was detected by its own radar. With CEC however, if another ship or aircraft detects a threat, any ship in the CEC network can potentially engage that threat because it appears to that ship’s CMS that, “their radar is my radar.” At last not only were Aegis units in a local force internally integrated into a coherent whole, but the entire force was capable of behaving as a single, fully integrated CMS.

But the potential of CEC was much bigger. (Then) Rear Admiral Rodney P. Rempt, Director of Theater Air and Missile Defense on the Navy Staff, saw a more sophisticated future still. A future in which the Navy’s tactical grid would one day be understood as, simply put, an agnostic network of weapons and sensors, controllable by any number of nodes, and without regard to where those weapons or sensors or controlling nodes might be deployed or even in which unit they existed. In the future, if an inbound threat were to be detected, this agnostic, dispersed grid would determine which sensor(s) would be most appropriate, and then, when necessary, the system would pair the most capable and best located weapon with that sensor(s) in order to efficiently engage the threat.

Imagine a hypersonic threat launched from a threat nation. In this agnostic grid, the launch is detected by multiple, mutually reinforcing methods, including satellites of various types and capabilities, as well as by other systems, including for example, intelligence networks. Immediately, other sensors are cued and brought to bear. The mode of a theater AN/TPY2 radar is automatically changed to maximize its tracking capability. As more sensors are automatically brought to bear, a precise track, including origin and aim-point is generated. At the same time, decisions are made at the strategic and operational levels; decisions dramatically aided by the application of artificial intelligence: Is the threat real? What asset(s) is under threat? What hard and soft-kill techniques and systems are best employed? What systems are both in position and possess the capability and capacity necessary for engagement? What is the optimal engagement timeline? What additional sensors should be brought to bear, and when? Jamming? Chaff? Decoys? From whom and when? Who shoots? When do they shoot? What ordnance do they shoot? How many rounds? Orders are automatically issued to concerned units, yet the entire network, including other decision nodes remain fully cognizant of the larger picture. The system has built in redundancies so that if one node is destroyed, another automatically and seamlessly steps in. And, all of these decisions can be automated, if desired, in order to maximize speed and the optimal response, provided that commanders allow for that automation. Ultimately, only the necessary and best systems are matched to the threat, at only the right time, maximizing effect and minimizing the waste of limited resources. The most effective and efficient method of engagement becomes routine.

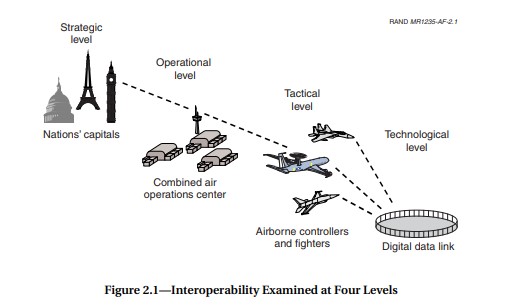

So, in fact, if one understands this networked grid of sensors, weapons and controlling nodes, whether at the tactical, operational, strategic or joint levels, then one begins to grasp both the operationalized reality of DMO, and many of the steps necessary in making DMO a reality.

Early, proto-progress has already been made in this direction. For example, Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air (NIFC-CA), enabled by CEC, allows ships to engage air threats located far over the shooter’s radar horizon. CEC also enables the “Engage-on-Remote capability which allows one unit to launch defensive missiles against a threat prior to detection of the threat with that ships own sensors. Also, in-flight retargeting allows dispersed units to contribute to an in-progress kill chain ensuring that the data remains as current as is possible. Still, there has been less incentive, post-Cold War, than might have otherwise been expected in a Naval Surface Force determined to lead in this arena. As the primary mission of the Navy shifted away from sea control and into power projection, directed against less sophisticated challengers, the need to operationalize this vision was far less dire. Moreover, in a resource constrained environment, leaps forward were forestalled. For some time, other needs and priorities took precedent.

The Motivation to Leap Forward

In January 2016, Admiral John M. Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) released a document entitled, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority. This paper discussed the necessity of a return to a larger strategy of Sea Control, following a lengthy, post-Cold War, period in which no blue-water challenger presented, and during which “Power Projection” was the Navy’s primary strategic approach. Moreover, this document set the table for the Navy’s return to “Great Power Competition,” sighting China and Russia as primary threats to U.S. and global interests. Perhaps most importantly, while DMO per se, was not mentioned, the CNO created a context in which DMO became the only viable solution: “We will not be able to ‘buy’ our way out of the challenges that we face. The budget environment will force tough choices but must also inspire new thinking.” The implications of this phrase were, and are, of enormous significance and these are only now coming more fully into the light.

In January, 2017, Vice Admiral Thomas S. Rowden, Commander, Naval Surface Forces, responded to the challenge posed by the CNO’s, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority with his Surface Force Strategy, Return to Sea Control. This document discussed an approach which it called “Distributed Lethality.” Distributed Lethality or “DL” may perhaps be best understood in the context of the catchphrase: “If it floats, it fights.” DL was intended as an operational and organizational principle, which will ultimately ensure that U.S. sea control will be reasserted and then sustained, despite a persistent decline in overall fleet size. DL was aimed to reinforce initiatives intended to drive collaboration and integration across warfighting domains; synergies, out of which the sum would exceed the parts. More specifically, and from a programmatic point of view, DL required an increase in the offensive and defensive capability and capacity of surface forces, now and in the future.

The 2017 Surface Force Strategy describes Distributed Lethality as being composed of three tenants:

- “Increase the lethality of all warships”: There is a clear tension between the undiminished, if not growing, mission sets assigned to surface ships, especially in light of the geographic demands associated with a return to Sea Control, and the total number of ships available. Moreover, in light of the collisions experienced in the summer of 2017, a lack of sufficient time and funding for maintenance was observed. Correction of this issue will inevitably result in fewer ships available at any given time as maintenance shortfalls are corrected.

Back to the tag-line, “if it floats, it fights,” this should be considered to represent the realized necessity that cruisers, destroyers, and frigates cannot be endlessly tied to High Value Units (HVU) whether those are amphibious ships or permanently constituted Carrier Strike Groups (CSG). Those ships must also have an ability to defend themselves, of course, but also a capability to strike hard in order to contribute to the larger mission of sea control. This suggests a compelling need to “upgun” these platforms, making them dramatically more capable both defensively and offensively.

- “Distribute offensive capability geographically”: This speaks to a wider dispersion of ships, in order to hold an enemy at risk from multiple attack axes, and force that enemy to defend an increased number of vulnerabilities, created by that dispersion. This point suggests what will become clear later, and that is the disaggregation of forces, which is part and parcel of DMO. So, in a genuine DMO environment, amphibious ships and aircraft carriers may be required to operate independently for periods of time.

In 2018, the Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group (CSG), demonstrated a new concept called, “Dynamic Force Employment (DFE).” The strike group was the first to venture north of the Arctic Circle in nearly three decades, spending significant time patrolling the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) Gap. Fundamentally, DFE speaks to deploying Navy forces in a much more diverse set of environments than those which have become common since the close of the Cold War. In the case of East Coast CSGs, standard deployments have featured passage through the Mediterranean to launch air strikes on Middle East targets from either U.S. 6th Fleet or U.S. 5th Fleet waters. According to the CNO, “…we don’t have to go too far back to sort of recapture what it means to be moving around the world as a strike group or an individual deployer and really kind of making everybody guess, hey where’s this team going to show up next? What are they going to bring to us next?” In short, there are tremendous incentives to spread the available force, for a variety of reasons, and this will require making each unit more capable of operating independently.

- “Give ships the right mix of resources to persist in a fight.” This point talks to an increase of defensive capability in ships, not only against kinetic threats, but also cyber and electronic warfare. Every ship must be a shooter and also every ship’s sensors must contribute to the larger network. Now all units become integrated, not only internally, but within the larger network, providing geometric synergies. In order to do this, it is essential that ships are able to send and received large amounts of timely and secure data as required, even when under cyber and electronic attack.

What is not discussed directly, but what must be appreciated, is the point that DMO is the necessary connective tissue, which must be built in order to stitch these up-gunned, widely dispersed ships together into a coherent whole.

In December 2018, the CNO released, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, Version 2.0. According to the CNO, this update more clearly aligned with both the latest National Security Strategy (NSS), released December 2017 and the supporting National Defense Strategy (NDS) of January 2018. While a new National Military Strategy (NMS) will follow, it is plain that these documents orient national security objectives more firmly toward great power competition with China and Russia.

It was here, in this document, that DMO made its first official, public appearance. The CNO called to “Continue to mature the Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) concept and key supporting concepts. Design the Large Scale Exercise (LSE) 2020 to test the effectiveness of DMO. LSE 2020 must include a plan to incorporate feedback and advance concepts in follow-on wargames, experiments, and exercises, and demonstrate significant advances in subsequent LSE events.”

Further, the Navy was tasked to: “Design and implement a comprehensive operational architecture to support DMO. This architecture will provide accurate, timely, and analyzed information to units, warfighting groups, and fleets. The architecture will include:

- A tactical grid to connect distributed nodes.

- Data storage, processing power, and technology stacks at the nodes.

- An overarching data strategy.

- Analytic tools such as artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML), and services that support fast, sound decisions.

Not only will DMO aid in the attack, but it will be critical in the defense. DMO will stretch an adversary’s ISR capabilities as wider areas much be searched to find “Blue” forces. Perhaps more important, widely dispersed forces will hurt “Red’s” ability to mass fires on Blue as their forces much also be more dispersed (though not linked in the same way that is possible in a full instantiation of DMO).

In other words, the time has arrived to define and build DMO. As to exactly how DMO will look and be employed, it is evident that the jury is still, very much, out. Not only is DMO the ultimate fruit of years of thought and effort, but it has become a necessity: Fleet size is not increasing, while demand for ships remains unabated. Sea Control requires a larger fleet – and if not a larger fleet, then new ways of thinking and fighting. DMO is the leading edge of this need.

Setting a New Table in the Fleet

With regard to the actual warfighting side of all of this, activity has been initiated. In February 2018, Admiral Scott Swift wrote a series of articles for Proceedings Magazine. In order to understand the possible Concept of Operations (CONOPS), which will be rendered possible by DMO, it is essential to read Admiral Swift’s essays. He describes a tactical grid, overseen by an operational/fleet-level Maritime Operations Center (MOC) which is charged by a Joint Forces Command (JFC) to implement various “effects,” in different campaigns (for example logistic, anti-submarine, amphibious) across time and space in order to achieve strategic goals.

This is a CONOPS which moves the conduct of warfare to a higher, more broadly-seeing level, above the long-standing primacy of the Carrier Strike Group. Further, it seems plain that in order to successfully carry out these campaign effects it will be necessary to disaggregate the once sacrosanct Carrier Strike Groups (CSGs). For example, a threat submarine is detected in the vicinity of a key logistics asset. The Theater Anti-Submarine Warfare Commander (TASWC) is tasked by the MOC to destroy the threat. In order to execute this task, the TASWC may have to draw a destroyer from a CSG, not only owing to proximity, but in order to bring that ship’s sensors and weapons, including helicopters, to bear on the target. Once the threat is passed, the destroyer returns to the CSG. In short, a general paucity of assets in any high-end fight, in any theater can only be addressed by the precise delivering of only the exact right force to the exact right place at the exact right time.

The point is that the big picture, regarding these campaigns and the respective effects associated with each campaign, resides up the chain-of-command. This picture, which is essential in operationalizing DMO, includes data of all sorts and not simply sensor data. Certainly, the issues associated with classified data being shared, system-to-system and unit-to-unit must be addressed, and this will necessarily be a major factor, requiring understanding and solution as the system evolves. However, while the current flow of data – and the ability to process that data – is directed to the top, this creates a potentially single point of failure. This speaks to a need in future instantiations of DMO to render the system “node-less,” by which is meant that more than one command is potentially capable of running the show. If the MOC is destroyed, the system will require that another command; another shore command or a CVN or a cruiser can seamlessly take over; this is the promise of Artificial Intelligence, more fully realized.

However, even if the desire to achieve DMO exists at all levels, a certain force level will be necessary in order to operationalize the concept. The question is, will that force exist? Currently, the Surface Force has specific numeric requirements for both Large Surface Combatants (LSC) and Small Surface Combatants (SSC). Whether these numbers are attainable is in doubt. Whether fleet size will continue to decline or whether the LCS class is a meaningful element in the DMO construct are, at this point, unknown. The Navy’s number one priority is building the Columbia class, and this means that in order to accomplish this effort sacrifices in other build programs, including the Surface Force, may be necessary.

A glimpse at what may be the Surface Force’s intention regarding the address of both raw ship numbers and the requirements of DMO’s operationalization, may have been on display at the 2019 Surface Navy Symposium, in Washington DC. The Navy may be arriving at the cusp of a true revolution in the shape of the Surface Force. In addition to the SSC and LSC types, which may be thought of as “classic” warships, what was freely discussed was the Surface Forces intention to embark upon the construction of an entirely new universe of Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USV), both large and medium in size. It is these platforms; the medium being primarily a weapons carrier and the medium being primarily a sensor platform, which may light the way to an actually dispersed force of weapons and sensors – achieved within a sustainable budget. These USVs will be substantially less expensive than fully manned, multi-mission ships, and they will be the essential population necessary to actualize the distributed grid of sensors and weapons which will enable DMO.

It is also important to consider that even as fleet size remains problematic, the advent of new systems provide a key opportunity, which can be geometrically capitalized upon through DMO. According to Dmitry Filipoff of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC):

“The Navy’s firepower is about to experience a serious transformation in only a few short years. Comparing firepower through a strike mile metric (warhead weight [pounds/1,000] × range in nautical miles × number of payloads equipped) reveals that putting LRASM into 15 percent of the surface fleet’s launch cells will increase its anti-ship firepower almost twentyfold over what it has today with Harpoon. New anti-ship missiles will cause the submarine community and heavy bomber force to also experience historic transformations in offensive firepower. The widespread introduction of these new weapons will present the U.S. Navy with one of the most important force development missions in its history. This dramatic increase in offensive firepower across such a broad swath of untapped force structure will put the Navy on the cusp of a sweeping revolution in tactics unlike anything seen since the birth of the aircraft carrier a century ago. How the Navy configures itself to unlock this opportunity could decide its success in a future war at sea. The Navy needs tacticians now more than ever.”

The Brain of DMO

If one considers that the vision of DMO has been described for some decades; that a requirement for DMO has been forwarded by the CNO; that a detailed thinking process has been undertaken in both the Surface Force and at the Fleet-level, and that budgetary limitations may force fundamental changes in Fleet composition, then the stage is set to begin thinking about the detailed connective tissue necessary to fully operationalize the concept.

First and foremost, in order to be fully realized, it is essential that Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) have nodes which are able to control the widely dispersed forces elemental to the system. All of these units must be stitched together by what may be thought of as a Battle Force Manager (BFM) resident in the many and varied (potential) command nodes. For purposes of security, this capability may be fully instantiated in some nodes, and only operationalized in others, as required. But, more than one unit will have to have full capability in order to guarantee the reliability and flexibility of the overall architecture.

With regard to the specific attributes of a BFM – the element of a command node which makes DMO command possible – the first requirement is the ability to ensure the composition of a single, commonly held and fully integrated picture of the battlespace, encompassing air, surface and subsurface domains, from the seabed to space, a true cross domain picture. Every node in the grid must possess a real-time, fire control quality picture, whether at the tactical or operational level, and this picture must be identical in every way to every other unit’s picture. Without this single, integrated, real-time, fire control quality picture, confidence is diminished and subordinate systems are dramatically sub-optimized.

It should be understood that this required picture of the battlespace currently does not exist. Despite the much touted “Common Operations Picture,” the Strike Group/Force, Maritime Operations Center (MOC) or Joint Force Commander’s (JFC) picture of the surrounding world is only similar to (but not tactically useful to) that of the Strike Group, the MOC or anyone else. One is reminded of a more powerful, Link 11 picture from the past. It may be useful at the operational level of warfare in that it provides broad, situational awareness, but it is completely insufficient to the challenges inherent to DMO.

As for the discrete capabilities resident in a BFM, it requires several:

- The BFM will monitor connectivity with every unit, on every circuit, automatically correcting issues of connectivity, and without operator intervention.

- The BFM “knows” in detail the nature of all ordnance and the weapons posture of every unit in the force. Who has what and what is the availability of that ordnance at any given time.

- Remote Control Capability: The BFM will be able to change the operational parameters of sensors and weapons systems, grid-wide, as appropriate. It also will know the mission, priority, survivability, and material condition of each unit, with regard to fuel and damage.

- Sensor/Weapons/Target Pairing Algorithms. The BFM will understand which sensor/weapon combinations are best versus any force threat and automatically issue commands to cause those weapons and sensors, no matter where they are located, to work seamlessly together. This will include both hard and soft-kill systems.

- A system which knows the operational limits of each node, including the weapons/sensor capability and capacity of each node, either manned or unmanned.

- The BFM will require access to and ability to sort enormous amounts of data, including intelligence, while at the same time aiding the decision makers by funneling only the most salient and correct prompts to the command team.

- The BFM will include aspects of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in order to ensure that decision-makers are presented only information which aids decisions, and holds other information in check unless called for. Moreover, this AI is the necessary “brain-power” which enables all other aspects of the BFM, and by extension, DMO.

There are “religious” issues in operationalizing a BFM. To a certain extent it means that a commanding officer may have to cede their absolute control of the systems subordinated to them. Moreover, it is not evident whether the Navy or industry fully grasps what will be necessary or of how to get there. What may be necessary in order to get “there” from “here” is a sort of modern-day, “Manhattan Project,” incorporating all of those companies and commands with either a stake in the problem or a critical capability. Otherwise, one may expect a suitable, capable BFM to only arrive in the long-range time-frame, and in balky fits and starts.

The Two Achilles Heels

Regardless, there are vulnerabilities here. Only now is the Navy awakening to the fact that a profound vulnerability exists in its ability to wage the sort of warfare that has been planned and worked toward for decades. Today, it is increasingly understood that Electronic Warfare (EW) is becoming a sort of sand foundation upon which the entire edifice of Navy warfighting capability shakily stands. In this case, EW should be thought of as the effort by which unfettered and complete access to the entire Electromagnetic Spectrum (ES) is ensured, rather than from the small, tactical perspective of Electronic Attack, Warfare Support and Protection.

Curiously, this situation has presented itself primarily as a result of the Navy’s focus upon an explosive growth in C5I (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Combat Systems and Intelligence) capability and capacity. Over time, a remarkable and unique ability to bend all elements of a widely dispersed force of weapons, sensors, and information into a single, integrated, global Combat Management System (CMS) has been developed for and by the U.S. Navy. This CMS enables implementation of the new strategy of DMO: Smart War. The BFM is the unit-level foundation which enables that ability. It will exist in all ships and aircraft, perhaps with different capabilities which can be enabled as necessary, making the entire system fully redundant and durable.

Unfortunately, any sensible adversary will recognize the advantage conferred on the U.S. Navy through an undisturbed access to the ES. In a Post-Arabian Gulf era, it becomes increasingly plain that this uninterrupted and secure flow will be a primary point of attack by any enemy possessing the means to do so. So, while it may be desirable to plan to employ this awesome capability, it also seems plain that in any real fight, full employment will be problematic.

Consequently, the Navy must develop the tactical approaches necessary in order to win in an ES-denied environment: An environment in which connections to higher authorities – any connections – may either be interrupted or severed. A CO is cut off from both leadership and external support for warfighting systems. What to do? Seek and destroy? Wait for a solution from above? Go to port? What about fuel?

Former Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Scott Swift evidently grasped the conflict between a maturing, global CMS and the possible loss of spectrum with the 2017 publication of his “Fighting Orders.” While the content of these fighting orders is classified, the shape of them can be guessed at, and perhaps they offer answers to some of the questions which arise in a “Dark Battle” scenario. Nevertheless, it seems essential that still more intense and critical thought be given to these issues, and now. And of equal import, these tactics should be practiced. Where shall I go? What shall I do?

Second, while this issue is somewhat beyond the specific conceptual scope of the DMO problem, there is an overwhelming need to address problems with the size of the Combat Logistic Force (CLF). This is particularly the case with regard to oilers. A combat ship refuels, in general, once every three days, but this can be stretched provided that increased risk is taken as far as available fuel is concerned. As it currently stands the number of replenishment ships available is a problem, even in a non-distributed environment. The days of the Navy possessing a sufficient numbers of oilers so that one could be attached to each CSG are gone.

What will happen as the fleet is broadly dispersed? Where will the fuel come from? Perhaps more worrisome, how can stealth be expected to be maintained when it must be clear to even the most casual enemy observers that not only are oilers are in terribly short supply, but that they travel directly from one HVU to another. Beyond this, oilers are operated by the Military Sealift Command (MSC). Not only are these ships manned by civilians who are in no way obligated to go into war zones, but they are completely defenseless without escorts and where oilers may warrant an escort contingent on par with that of capital ships.

Opening the Aperture

With distribution comes challenges. Not only in terms of connectivity but in terms of the discrete elements in the tactical grid. Far from either shore-based assets or the air wing resident in the aircraft carrier, one must ask how ships will be able to maintain a picture of the surrounding world beyond the range of their own radar. Any hostile surface ship, for example, more than 20 or so miles away may be undetected and undetectable. Not only does this create vulnerabilities for the single unit, but it severely limits the ability of controlling nodes – at any level – to fully grasp the battlespace. A larger, more complete understanding of the tactical grid is required.

Owing to issues ranging from maintenance to crew availability even ships equipped with two helicopters cannot sustain around-the-clock air operations – far from it. It seems plain that the solution to this must lie in a greatly expanded capability and capacity in terms of ship launched and recovered Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV). UAVs will serve several primary needs in a DMO environment; sensors, weapons carriers, and communication assets. First, small UAVs with sensors can greatly expand the footprint of dispersed ships. And, if they are long duration, this footprint can be maintained around the clock. A good, early example of this type of UAV is the Boeing Insitu ScanEagle. ScanEagle carries a stabilized electro-optical and/or infrared camera on a lightweight inertial stabilized turret system, and an integrated communications system having a range of over 62 miles (100 km), and it has a flight endurance of over 20 hours. Subsequently, improvements to the original design added the ability to carry Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), infrared cameras, and improved navigation systems.

Second, these UAVs can extend the attack reach of widely dispersed units. Today, the MQ-8B “Firehawk” is capable of carrying hellfire missiles, Viper Strike laser-guided glide weapons, and, in particular, pods carrying the Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System (APKWS), a laser-guided 70 mm (2.75 in) folding-fin rocket. Depending upon the size of the flight deck, ranging from the very small in the case of LCS class ships to the larger flight decks in amphibious ships, like LPD class ships, the variety and capability of UAVs seems limited only by imagination.

Third, is the matter of communications relay, without which the “distributed” part of DMO ceases to exist. As it stands today, Navy communications face a number of vulnerabilities, not the least of which is a reliance on commercial satellite channels. By lowering the connectivity grid from satellite level to long-endurance UAVs, the grid gains a redundancy which could make the difference between fighting the next war, “in the dark,” and fully realizing the potential of DMO.

The same thinking applies to Unmanned Surface Vessels (USV). Based upon the presentations given by the senior officers of the Surface Warfare Community at the 2019 Surface Navy Association (SNA) it seems abundantly clear that a major shift may be in the offing. Not only is the Surface Force activating a squadron aimed at USV experimentation and development, but it is also plain that the Navy intends to move into the USV world in a big way and in the near future. Evidently, these USVs will be divided into two primary classes: Medium-sized, which will be carriers of ordnance, and small-sized which will be sensor platforms, potentially of great variety.

With regard to the Medium USV, the need is abundantly clear. A modern Navy has the need for many and varied types of weapons, ranging from short-range point defense to ballistic missile interceptors, to anti-submarine weapons to long-range surface and land strike missiles. The number of cells resident in even the largest Vertical Launching System (VLS) is 122. It is easy to envision these weapons being expended quickly in a real shooting war. Will floating magazines help remediate this problem? Will they potentially be able to host directed energy weapons?

As for the small USVs, what sort of sensors are under consideration? The problem is that modern radars generally emit a very specific signal, and are consequently, easily identifiable. What can be done to protect sensor UAVs from detection and destruction? If they are only intended to be activated for short periods and then moved, how useful can they be? Or, if they are all passive sensors, what is the nature and utility of these. Regardless, they will have to pass data and this also creates a threat of counter-detection.

Today, not much is yet known about the potential shape or nature of these USVs, but they are coming. Having said that, there are aspects of these USVs which should be of enormous concern and interest. First, what is the likely stay time on station for these units? How will they arrive on station and what sort of mobility will they have? Is it possible for them to move, perhaps hundreds of miles from station-to-station? What power source will they employ? Potentially, either variety of USV will have significant power needs, which speaks to greater energy production than may be found in modern batteries.

Perhaps more important, and this is especially the case of those USVs which carry sensors, how will detection by enemy forces and subsequent capture or destruction be avoided? How seaworthy? Semi-submersible weapons carriers? How will they be serviced and how often will that be required? Perhaps more than any element of a DMO instantiation, with the possible exception of a BFM, the nature of these USVs is critical.

In the Long Run

This discussion only touches upon the surface of what could well be called a “plastic” discussion. In the course of operationalizing a viable DMO system and concept, a voyage of discovery will be necessary, and in this, both blind alleys and new approaches will be discovered. What is essential is a clear understanding of what DMO might look like so that a path to a solution can then begin to be envisioned. Further, it is critical that those involved in these discussions put aside their parochial views in favor of achieving and maintaining a critical edge which will ensure American command of the seas for decades to come. It will take much more than directed energy weapons or UAVs or AI to maintain this command. In order to attain this goal, the necessary effort lies in stitching these systems all together into a single, fully integrated Combat Management System, lying far beyond that which is possible today.

Steve McJessy is a Reserve Commander, living in San Diego. He also works in the defense industry supporting Navy programs.

Kevin Eyer is a retired Navy Captain. He served in seven cruisers, commanding three Aegis cruisers: USS Thomas S. Gates (CG-51), Shiloh (CG-67), and Chancellorsville (CG-62).

These views are presented in a personal capacity.

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (Nov. 8, 2018) The aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76), left, and the Japanese helicopter destroyer JS Hyuga (DDH 181), right, sail in formation with 16 other ships from the U.S. Navy and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) during Keen Sword 2019. Keen Sword 2019 is a joint, bilateral field-training exercise involving U.S. military and JMSDF personnel, designed to increase combat readiness and interoperability of the Japan-U.S. alliance. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kaila V. Peters)