China’s Defense & Foreign Policy Topic Week

By Jeffrey Payne

Consistent discussions over the past several years between the United States and China on counterterrorism (CT) cooperation represented an opportunity during a time of tension. The logic behind these discussions is simple: both Washington and Beijing’s interests generally run in parallel when it comes to stopping violent extremist organizations. Yet, despite detailed conversations in several formats, no cooperative plan has emerged. The reasons for this are multifaceted, but they center on this point: the cost of cooperation outweigh the benefits, on both sides. The United States, for its part, should accept that efforts to cooperate with China on CT are not viable, at least in the near term, and instead should focus on expanding CT cooperation with other Asia-Pacific partners.

The CT Problem Set

Degrading and destroying violent extremist organizations has been a national security priority of the United States for several decades and in that time the federal government developed a host of tools for countering terror that vary from intercepting illicit financial transactions to military operations intent on eliminating terrorist organizations. United States CT operations have evolved from those focusing on extremists in South Asia to today becoming a global effort featuring partnerships with dozens of states. CT partnerships have not only assisted in deepening military relationships between the United States and other countries, but also became an irreplaceable resource for intelligence gathering, capacity building, and economic development.

The threats posed by violent extremists continue to diversify. CT is much more than a military or security force strike. Too many both outside and inside of government forget the investments in supply chains, facilities, training, intelligence, community outreach, judicial and police services, development, and simple face-to-face discussions among partners that are needed for CT efforts to be successful. Therefore, many partnerships the United States built in past decades are not simply about combat. Many partners are engaged in the CT fight without contributing military or security service personnel. Quite a few are sources of information about violent extremists, while others provide needed equipment and supplies. Still more, either due to domestic considerations or external limitations, are involved in efforts more accurately described as countering violent extremism (CVE), a term that addresses a host of actions targeting the economic structures, communities, laws, and social fabric, among others, of a country or region in order to inhibit the spread of violent extremism. CVE is distinct from CT, but still related through the overarching objective of ending the threats posed by violent extremism.

What the evolution of CT, and by extension CVE, reveals is that there a multitude of ways in which countries can use the resources at their disposal to erode terrorism. The United States has partnered with dozens of countries in various capacities and in varying intensity to conduct CT operations. Some of these partnerships were easy to build as they merely added on to existing alliances. Still others were issue-focused partners that coordinated on CT-related operations solely. When it came to countering terrorism, preexisting difficulties do not inherently close the door on state-to-state cooperation. Therefore, the fight against terrorism has evolved in such a way where a country like China can become a partner to the degree in which it is most comfortable. So long as partnerships are conducted in good faith by both parties, there should not be insurmountable obstacles to cooperation.

Why Cooperation with China is Unlikely

The U.S.-China bilateral relationship has long been complicated. Beijing sees itself as ascendant and has pursued actions that signal its intention to become a regional hegemon and alter the dynamics of the region. The United States, the principal architect of the existing regional order and an ally to four of China’s neighbors, seeks to see China rise without fundamentally displacing its position in the Asia-Pacific, nor dismantling the rules and institutions that define the current regional environment. When it comes to the Asia Pacific, the United States and China are in competition.

Yet, outside of the Asia Pacific, the interests of the United States and China are seemingly not as complicated. In fact, on many global issues the view of both Washington and Beijing are complimentary. Thus, a situation exists where the United States and China ‘compete locally but can cooperate globally.’ A more global China, even one that is risk averse, has slowly but steadily gained experience in the cultural context of foreign regions, while also becoming more tied to foreign countries through trade and diplomacy. Today, China enjoys the status of a major power. China is relatively stable internally, possesses the second largest economy, and is building one of the world’s largest and most advanced militaries. It is also a country that increasingly has to concern itself with terrorism, both domestically and as it relates to its foreign investments and expatriate population.

For much of the bilateral relationship, the United States and China have been interested in each other and the balance of power in the Asia-Pacific. Beijing’s engagement beyond the Pacific intensified during the administration of Hu Jintao and became solidified in the current Xi Jinping era. China substantially deepened its economic and diplomatic engagement throughout Africa with China’s banking institutions and commercial development corporations becoming the go-to source of infrastructural development. China invigorated its outreach to Europe both in an effort to gain greater market share for its exports in those economies, but to also develop the relationship networks needed for a stronger continental footing. China gradually and quietly intensified relationships throughout the Middle East, particularly in the Gulf and with other regional resource-rich countries. China’s footprint in Latin America is often overlooked by China watchers throughout the world, but Chinese diplomacy and money have made quite the impact over the past decade. Finally, China ratcheted up engagement with the regions it borders: Central Asia, South Asia, and East Asia. Taking as a whole, China’s foreign engagement has made it a global actor that is quickly gaining the capacity to compete with the United States. In fact, negative perceptions regarding the current United States administration’s willingness to retain its traditional global leadership role have led some to look to China.

China’s successful emergence as a global power comes with a cost. One of these costs is that as China became more engaged around the world, the probability of being targeted by violent extremists increased. Chinese nationals or Chinese investments have been targeted by extremists in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Libya, Kyrgyzstan, and Iraq. Increased risk from extremists have forced evacuations or increased security in Yemen, Kenya, and the Philippines, among others. A handful of attacks have also occurred inside Chinese territory. The first factor explaining why China is becoming more affected by terrorism is its willingness to engage in foreign projects within unstable countries or near conflict zones. As Rafaello Pantucci stated in a recent opinion piece, “turn to today, and as China reaches out to the world through President Xi Jinping’s belt and road plan, Beijing is becoming more of a terrorist target.” Such risk inevitably puts Chinese citizens and capital in close proximity to violent extremist organizations.

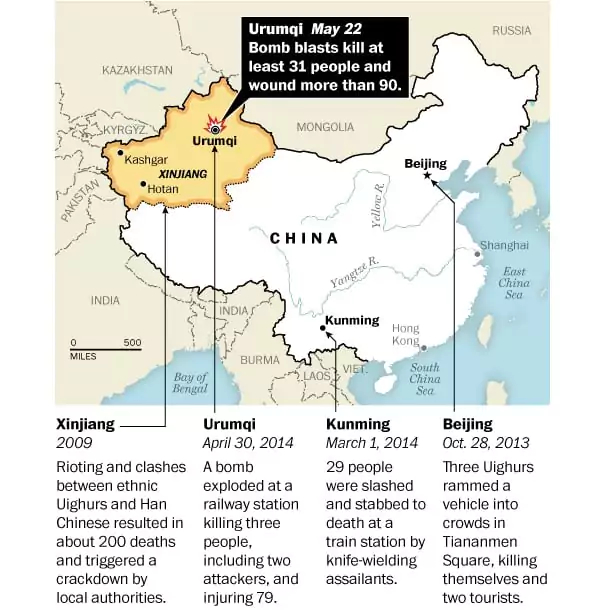

China’s greater international political standing is a second factor and its rise has also seen it become more involved in global governance. It is a major contributor to United Nations Peacekeeping Operations (UNPKO), was an active player in the P5+1 Talks regarding Iran’s nuclear program, and created several major international organizations, like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, that indirectly tie China to the internal politics of other states. The third and most often mentioned factor is the emergence of violent extremism among minorities in China, with the Uyghurs most often discussed, who have adopted violent measures as a means for achieving political aims. Beijing claims these violent extremists are a major threat to China’s stability and growth, while consistently emphasizing that violent extremists are tied to terrorist organizations beyond China’s borders.

The first and second factors are not inherently politically charged issues for the United States, but the same cannot be said for the issue of minority violence. China’s position regarding homegrown violent extremism presents a human rights concern for Washington. Past United States’ administrations have made a distinction between those from minority groups who are actual violent extremists and those who are peaceful political dissidents. The United States has objected to Beijing’s domestic actions in regard to violent extremism due to apprehensions that Chinese authorities are using the threat of terror to repress ethnic and religious minorities, many of whom are in no way tied to violent extremism. But there is no mistaking that some Chinese citizens are violent extremists. A small portion of Uyghur extremists are affiliated with several terrorist organizations including the Turkistan Islamic Party, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and Daesh/ISIL, among others. In 2001, the United States designated the East Turkistan Islamic Movement, a violent organization that claimed to act for Uyghur rights, as a terrorist organization. But it remains unlikely that the United States and China will soon solve their disagreements over how China classifies terrorism within its own borders.

China’s interests in combating terrorism go beyond the question of violent extremists among ethnic and religious minorities in China. China is increasingly concerned about the impact of violent extremism in Pakistan, has consistently voiced its support for efforts to defeat Daesh, and has publicly condemned the actions of groups like Boko Haram and al Shabaab. According to Beijing, such terrorist groups not only put Chinese citizens and investments in harm’s way, but their existence spreads regional instability. The United States is actively involved in multilateral efforts to defeat violent extremism around the globe, including groups that China has publicly opposed. As the United States and China both share an interest in seeing such terrorist organizations defeated, it is logical for the two states to discuss cooperative action. The recent Diplomatic and Security Dialogue between senior leaders from the United States and China in June of 2017 highlighted how China wishes not only to see the demise of Daesh, but also hopes to contribute to such an undertaking.

June discussions on CT are the most recent of a series of bilateral meetings between the United States and China that discussed CT cooperation in Track I, Track 1.5, and Track II formats. Both sides agree that there is a shared interest, but over the course of the past five years these discussions have not generated any tangible plan of action as to how to actually cooperate. The problem is one of good faith. China has long been apprehensive about United States military actions in the developing world, specifically in the Middle East. Given that the most intensive CT operations target Middle East-based terrorist organizations, this is not an easy hurdle to clear. Chinese officials and analysts regular discuss the reasons that the invasion of Iraq in 2003 is a root cause of current instability in the Middle East and have more recently expressed displeasure in what they see as the United States’ and European allies’ disregard of a UN mandate during the civil war in Libya. China fears that if it cooperates with the United States it could become a party to a regional crisis or end up providing diplomatic cover for an overly-ambitious United States military operation.

Furthermore, China continues to differ in how to best defeat certain terrorist organizations. Daesh became a regional threat in the Middle East and is a contributing factor to the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Syria and the larger Levant. United States policy is committed to defeating Daesh and has created the international coalition to Counter ISIL to assist in that goal, but it and its allies maintain that defeating Daesh does not mean supporting the Assad regime, which initiated the humanitarian crisis in Syria that in turn provided space for Daesh to gain power while the regime continues to commit human rights abuses. China is less concerned with the human rights abuses of the Assad regime and argues that stability in Syria is of paramount importance. The only person inside Syria that has any possibility to create stability is Assad, at least according to Beijing.

Beyond specific objections relating to United States CT approaches, China has also been consistently apprehensive about joining multilateral security efforts, with the exception of those operating under a United Nations banner or those created and largely controlled by Beijing. Beijing has signaled that joining multilateral security efforts will provide China little leverage over decision making inside these organizations. China’s longstanding foreign policy principles of non-interference and respect for sovereignty continue to matter when it comes to foreign policy, even if only as talking points. When they are abandoned for national interest, Beijing prefers to engage countries on a bilateral level, especially when security issues are at stake so as to optimally manage perceptions of interference. China’s concerns over Pakistan-based violent extremism, for instance, are largely encapsulated within the bilateral relationship it has with Islamabad. Finally, arguments are regularly put forward stating that China is not yet capable of sending military units far from its borders for long-term military action and doing so would put too great a burden on its security forces. Such concerns have not kept China from engaging in long-term UNPKO or from maintaining a consistent People’s Liberation Army Navy presence near the Horn of Africa since 2008 as part of a counter piracy and commercial escort mission, however.

Given China’s hesitations regarding security-based cooperative action and its different reading of how to address threats, it should come as no surprise the United States is increasingly skeptical of cooperation. The United States neither expects nor would necessarily welcome Chinese military units to engage in existing CT operations. Both the United States Department of Defense and the Department of State are quite familiar with China’s hesitation with the United States’ preferred approach of multilateralism. When the offer of cooperation has been extended by China, the United States has most often responded with an affirmative response followed by a request of how China wishes to specifically cooperate. When nothing specific is mentioned, which is a common occurrence, there have been attempts to offer China a role that seeks to address concerns from the Chinese side while also being of value to larger CT efforts. China has in the past run effective training programs for police officers and first responders, along with possessing a modern and sophisticated supply chain within its security organs. Each of these and more has been floated as possible avenues by which China can become involved in CVE initiatives. Such efforts are not directly tied to CT operations, but provide a support function that could be of great help. No real traction has come from any of these ideas.

When specificity is offered by China it is often conditional and will conflict with a tenant of existing United States policy. For instance, the United States should accept China’s view of Assad’s future in Syria before progress can be made on cooperating over Daesh. This is not an easy option for the United States given how it sees Assad’s crimes against his own people. Another commonality is for the United States and China to build a shared framework for approaching CT that can either be a part of the larger bilateral relationship or be the basis for a new multilateral effort. Beyond being unproductive given existing multilateral efforts, China has consistently used engagements on specific issues to get the United States to affirm its “new type of great power relations” concept. The United States refuses such a concept because it could undermine existing institutions that constitute the existing international system.

Consistent conversation on the issue of CT has led to no tangible avenue for cooperation. This failure does not mean that the United States and China cannot cooperate on a host of other issues internationally, nor does it mean that China is not serious about countering terrorist organizations. What past discussions have revealed is that what sounds like a good idea theoretically is impeded by other elements of each country’s respective national interests. For the United States, CT cooperation with China is not viable in the current environment and attention should be directed to other actors in the Asia-Pacific.

Do More with Existing Partners in Asia

United States CT operations are concentrated in certain regions: the Levant, the Gulf, North Africa, East Africa, and South Asia. For our partners in the Asia-Pacific, they too face threats from terrorist organizations. The United States can leverage its relationships in the Asia-Pacific to expand CT efforts.

To start with, the United States can and should do more with regional allies. Existing CT cooperation exists with all of the allies in the Asia Pacific, but given the depth of ties with these states, more could be developed and more could be asked. Australia, already experienced with both CT and CVE efforts, has progressively shown greater strategic interest in areas beyond the Asia-Pacific. Intensified CT joint training, particularly given the United States Marine barracks in Darwin provides logistical ease, is a prime opportunity. Australia is a participatory member of the International Coalition to Defeat ISIL and that model could be a source point for intensified conversations about other CT concerns, such as the dangers posed by al-Nusra, illicit networks operating in the Horn of Africa, and other similar threats. The recent visit by Secretary Mattis had an emphasis on CT cooperation. Momentum on intensified CT cooperation should not be wasted by the current U.S. administration.

South Korea and Japan have both invested in CT capability and both are also members of the current anti-ISIL coalition. Seoul and Tokyo are also increasingly interested in regions beyond the Asia-Pacific and gaining expertise about the regional dynamics of Africa, the Middle East, and other regions where the United States conducts CT operations. In short, our allies in Northeast Asia are casting their eyes beyond their neighborhood and are doing so within existing international structures – both of which are welcomed by Washington. Northeast Asia is without a doubt a complicated neighborhood right now given China’s regional ambitions and the nuclear threat posed by North Korea, but such complications should not erase an opportunity for deepening regional partnership while also enhancing regional capacity on CT. Japan’s capabilities to establish CT-focused training programs have been routinely discussed by Prime Minister Abe’s government and the United States, as part of its alliance with Japan, could bolster political will around such efforts. South Korea-United States bilateral dialogues on CT are an established component of the relationship and represent a pathway for further cooperative action.

The Philippines is not only a longtime ally, but is the focus of one of the United States military’s oldest CT operations. United States Special Forces have worked alongside the Armed Force of the Philippines (AFP) in training exercises, capacity building programs, and operations intended to degrade the capabilities of the Abu Sayyaf terrorist group and other extremist groups located in western Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. While this cooperation continues, the Duterte administration has made the military relationship with the United States a contentious political issue. Yet, intensified government-to-government contact, including high-level visits by the U.S. administration could do much to ease any existing tensions. Massaging the relationship with the Philippines could open additional doors for cooperative action, such as providing further assistance to AFP operations relating to Davao City and working with the Philippines government to expand the scope of cooperation beyond the Philippines border.

Allies offer the most immediate opportunities for CT cooperation, but other regional actors should not be ignored. Repaired relations with New Zealand could include a focus on CT assistance in Southeast Asia, a region where New Zealand has ample experience through its record of peacekeeping. Indonesia, a rising regional economic powerhouse, not only continues to confront its own violent extremist threat, but also is connected with both its Southeast Asian neighbors and with other Muslim-majority societies in the MENA region that face extremist threats. Thus far, the bilateral relationship between Jakarta and Washington on security matters has been slow to develop, but as with the Philippines leaps could be achieved by simply investing direct government-to-government attention. Many hesitations about cooperating with the United States can be countered merely by key leaders showing up.

Conclusion

It is past time to recognize that CT cooperation is a remote possibility for the United States and China. Such a realization does not undermine the prospects of cooperation in other areas, nor ignore the threats violent extremists pose to China and its citizens. Discussions of CT simply exist too near the orbit of complex issues in the bilateral relationship that neither party is willing to jettison. The United States’ interest in confronting violent extremism around the globe will continue to be viewed as vital to national security. The United States would find rewards if instead it intensified efforts with regional allies and invested the legwork needed to map out new partnerships.

Jeffrey Payne is the Manager of Academic Affairs at the Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies in Washington, DC. The views expressed in this article are his alone and do not represent the official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Featured Image: Chinese Armed Police soldiers shake hands with their Belarus peers at the opening ceremony of the United Shield-2017 joint anti-terrorism drill on July 11, 2017. The United Shield-2017 joint anti-terrorism drill, which was jointly held for the first time by the Chinese People’s Armed Police Force (APF) and the Internal Troops of the Belarusian Interior Ministry, started in the suburb of Minsk, capital of Belarus, on July 11, 2017. (81.cn/Xie Xinbo)