Have you ever heard of Nauru? This small island of the South Pacific is not very well-known but its story could be representative of the one of humanity.

A little history

Nauru was formerly called “pleasant island” and if it may have been really pleasant, it is no longer the best tourist destination.

With its 21 square kilometers for less than 10 000 inhabitants, it is the second smallest state in the world after the Vatican.

As many islands in the South Pacific, Nauru was colonised by a European state in the 19th century. The German Empire settled in the small island to make it part of its protectorate of the Marshall Islands.

During this time, the Australian prospector Albert Fuller Ellis discovered phosphate in Nauru’s underground. Phosphate is widely used in agriculture and is an essential component in fertiliser and feed.

After contracting an arrangement with the German administration, Ellis began mining in 1906.

But soon, WWI happened and Australia, New Zealand and the UK took over Nauru and started administrating the island and its phosphate. In 1923, the League of Nations gave Australia a trustee mandate over Nauru, with the United Kingdom and New Zealand as co-trustee.

Then the Japanese troops occupied the small island during WWII. It’s only in 1968 that Nauru gained its independence, shortly after buying the assets of the phosphate companies. This enabled Nauru to become one of the richest island in the South Pacific.

All Used Up

Between 1968 and 2002, Nauru exported 43 millions of tons of phosphate for an amount of 3,6 billions Australian dollars. But 21 square kilometers is a small area to have mines everywhere and now there is no phosphate left.

The Land of the Fat

In the meantime, people of Nauru started having access to a lot of money and to live the American way. Apart from phosphate, there are very few resources on the island. Therefore, most products were imported, including big American cars and fat food. It did not take long before inhabitants of Nauru became the most obese people in the world, which led the British journal ‘The Independent’ to call Nauru ‘the land of the fat’. Indeed, according to the World Health Organisation, 97 percent of men and 93 percent of women in Nauru are overweight or obese.

Those people who used to eat fish, coconuts and root vegetables now eat imported processed foods which are high in sugar and fat. Now, more than 40% of the population is affected with type 2 diabetes, cancers, kidney and heart disease.

Money, Money, Money

In the 80’s, Nauru was very rich. However, soon, growing corruption, bad investments and big spending on the government’s side made Nauru a very indebt country.

Nauru’s bank accounts are all in Australia, simply because there are no banks in Nauru (the only one left, the National Bank of Nauru is actually insolvent). In October 2014, an Australian court ruled that Nauru owed 16 million Australian dollars to US-based investment fund Firebird, which had lent money to the government of the small island. But the government of Nauru did not respect the court’s decision and it defaulted on the bonds. Since it did not reimburse Firebird, its debt soon amounted to 31 million Australian dollars. Firebird had then prevented Nauru’s government from accessing its bank accounts held in Australia and had frozen all of Nauru’s acounts. Nauru’s administration immediately warned that it was about to run out of cash and that it could not pay for essential goods, such as generator fuel, and public servant salaries. It would have been a national disaster because from the 10% people who have a job in Nauru, 95% are employed by the government. Nauru’s unemployment rate is estimated to be 90 percent. The government clearly needed money to buy fuel to produce energy, since it did not invest in renewable energies. Without fuel, no possibility to have a functioning hospital or to have fresh water, because sea water is pumped and then desalinated, a process that needs lot of energy. And without fuel, all the planes stick to the ground.

Finally, Nauru merely won the court case and did not have to repay Firebird. Is this decision linked to the fact that Nauru hosts Australia asylum-seekers in a detention center? Maybe. If all the planes stick to the ground, that means that the center is no longer running; every day, new asylum seekers come and go, and so do doctors, lawyers and others.

Furthermore, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) declared that although Nauru’s administration has a strong public mandate to implement economic reforms, in the absence of an alternative to phosphate mining, the medium-term outlook is for continued dependence on external assistance (mainly from Australia and China). In 2007, the ADB estimated Nauru GDP per capita at $2,400 to $2,715. That’s not a lot!

Public enemy n°1

In the 1990s, Nauru became a tax heaven and started selling passports to foreign nationals.

It led the inter-governmental body based in Paris, the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF), to add Nauru to its list of 15 non-cooperative countries in its fight against money laundering. Experts estimate that Nauru triggered a $5 trillion shadow economy. According to Viktor Melnikov, previous deputy chairman of Russia’s central bank, in 1998 Russian criminals laundered about $70 billion through Nauru. The island started suffering the harshest sanctions imposed on any country, harsher than those against Iraq and Yugoslavia. European banks did no longer allow any dollar-denominated transactions which involved Nauru. This is why in 2003, under pressure from FATF, the government of Nauru introduced anti-avoidance legislation. The result was quick: foreign capitals left the island. Two years later, satisfied by the legislation and its effects, the FATF removed Nauru from its black list.

The difficult relationship between Australia and Nauru

There is a very special relation between Australia and Nauru. Australia administered Nauru from 1914 to 1968. However, Nauru did not seem entirely satisfied with the Australian administration. Indeed, in 1989, Nauru took legal action against its former master in front of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Nauru was attacking the Australian way of administrating the little island and in particular Australia’s failure to remedy the environmental damage caused by phosphate mining.

You can find the judgement here.

In 1993, Nauru and Australia notified the ICJ that, having reached a settlement, the two parties had agreed to discontinue the proceedings : Australia had offered Nauru an out-of-court settlement of 2.5 million Australian dollars annually for 20 years.

In 2001, Australia asked Nauru to help it fight immigration. The two countries signed an agreement known as “the Pacific solution”. In exchange for an important economic aid, the small island of 21 square meters agreed to host a detention center for people seeking asylum in Australia. This agreement officially came to an end in 2007 but the two countries are still looking for a solution to help Nauru’s economy survive. Which means the detention center is still running.

Furthermore, we know that a significant portion of Nauru’s income comes in the form of aid from Australia. In 2008, Australia committed €17 million in aid for the 2009 financial year, along with assistance for “a plan aimed at helping Nauru to survive without aid.”

In November 2014, the Australian independent Tasmanian MP Andrew Wilkie wrote to the International Criminal Court (ICC) asking it to investigate Abbott’s government for crimes against humanity over its treatment of asylum seekers .

Abbott’s government has consistently argued that its offshore processing and resettlement policies have stopped people attempting to arrive in Australia by boat and therefore saved lives. For the moment, asylum seekers who arrive to Australia by boat will be refused visas and the ‘Pacific Solution’ is implemented; under this policy, asylum seekers arriving without authorisation are sent to Australian-funded detention camps in Nauru or the island of Manus in Papua New-Guinea rather than being allowed to claim asylum on the Australian mainland. In September 2014, Canberra paid 40 million Australian dollars to the government of Cambodia for Phnom Penh to welcome asylum seekers from Australia. Furthermore, a new legislation from September 2014 will make it harder for asylum seekers already in Australia who arrived by boat to make visa applications.

Nauru’s diplomacy

After having sold many passports, the Nauru’s government decided to communicate on positive actions.

In 2008, immediately after Kosovo declared independence from Serbia, Nauru recognised it as an independent country.

One year later, along with Russia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, Nauru recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two breakaway regions from Georgia. After a war with Georgia, Moscow had tried to secure international recognition for the two regions. According to the Russian newspaper ‘Kommersant’, Russia gave $50 million in humanitarian aid to the little Pacific state.

Nauru is Kiribati’s neighbour, an atoll famous for disappearing and for sending the first climate change refugees abroad, to Fiji. With no space left to grow food or to live, no fresh water and always more refugees coming, the people of Nauru might also desert their island soon.

Hopefully, the story of the small island of Nauru will not be a sample to the history of humanity’s little island orbiting the sun!

Alix is a writer, researcher, and correspondent on the Asia-Pacific region for Marine Renewable Energy LTD. She previously served as a maritime policy advisor to the New Zealand Consul General in New Caledonia and as the French Navy’s Deputy Bureau Chief for State Action at Sea, New Caledonia Maritime Zone

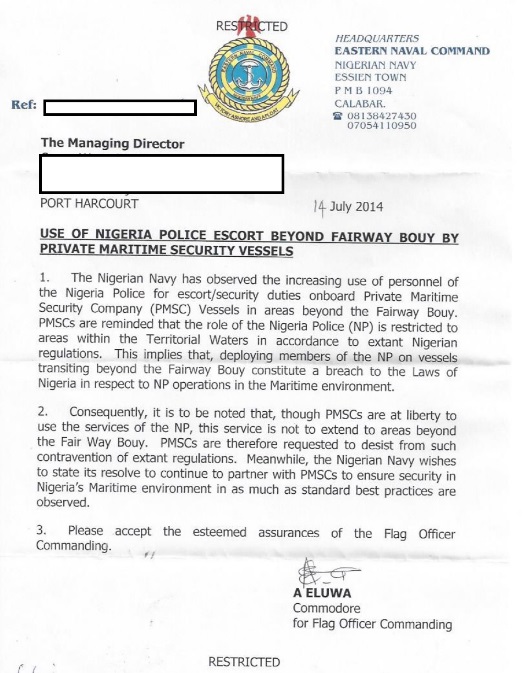

![[Photo: “Acknowledgement of receipt” provided by a security provider to a client as “evidence” of approval to embark naval personnel.]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/security-receipt.jpg)

![[Photo: Damage to the bridge of SP BRUSSELS from the firefight on the bridge. (Source: withheld)]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Brussels-damage.jpg)

![[Photo: The SEA STERLING on Lagos roads in April 2014. (Dirk Steffen)]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Sea-Sterline.jpg)

![[Photo: NNS IKOT-ABASI, pictured here on Lagos roads in April 2014, responded to the distress call made by the SP BRUSSELS. (Dirk Steffen)]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/IKOT-ABASI.jpg)