This article originally appeared on the CDA Institute and was republished with permission. You can find the article in its original form here.

CDA Institute guest contributor Ken Hansen, a research fellow at Dalhousie’s CFPS, comments on the necessity of logistics in light of the decommissioning of HMCS Protecteur and HMCS Preserver.

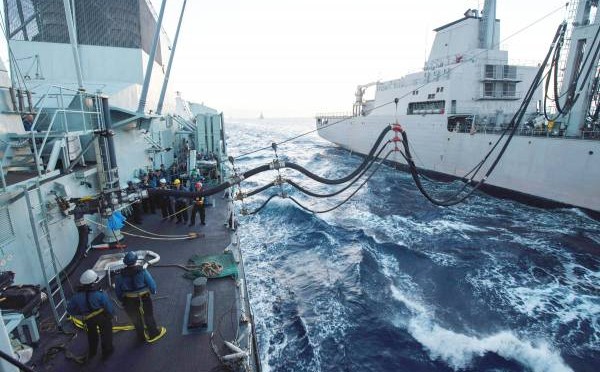

The loss of at-sea replenishment capability has dropped the Royal Canadian Navy’s (RCN) standing from a blue-water, global force projection navy to an offshore territorial defence organization. The major fire in HMCS Protecteur and the severe rust-out problems in HMCS Preserver have resulted in the decommissioning of both ships and a logistical crisis that requires corrective action. Some signs for optimism have arisen recently in two contracts with the Spanish and Chilean navies for the use of two of their replenishment ships for a period of 40 days each. The total cost is rumoured to be approximately $160M CAD.

Forty days of sea time will allow each coastal formation to run an exercise involving replenishment at sea training and perhaps a tactical scenario for task group readiness. By doing this, Canadian sailors will get a chance to preserve complex and perishable skills that are vitally important in modern naval operations.

Replenishment at sea involves all of the ship’s departments. Navigation, operations, deck, engineering, and supply must all understand the sequence of events intimately if all is to go as planned. While sailing a ship alongside another at 20 to40 metres distance is demanding in calm seas, at night and in rough weather is no place to be doing this for the first time. The most graphic example of what can go wrong occurred off the coast of South Africa on the night of 18 February 1982, when the South African navy’s replenishment ship SAS Tafelberg rammed and sank the frigate SAS President Krugerafter the latter made the fatal mistake of turning in front of the bigger ship. Sixteen sailors were lost in this incident.

The South African accident occurred due to confusion in close-quarters manoeuvring during an anti-submarine exercise. Replenishment is a common activity in multi-ship exercises and is often scheduled to coincide with other tactical ‘challenges’ to raise the complexity of challenges facing commanders. I have had many first-hand experiences with these exercises and their hazards. On one occasion, north of Iceland, nearly four hours spent attempting to refuel in stormy winter conditions resulted in a mere 20 cubic meters of fuel transferred, much damage to the equipment, plus lots of frozen fingers and faces from the spray. We nearly lost one sailor overboard from the icy deck before the two captains conferred and agreed to call it off. Another occasion resulted in a side-swiping by our ship of the much larger oiler. We slid backward along her side, leaving a long smear of distinctive Canadian naval paint on her hull and eventually cleared her stern ignominiously. Everyone knew trying to extricate ourselves by going the other way was potentially fatal.

The history of replenishment at sea training is full of such near misses and embarrassing moments. The calamity that befell President Kruger is actually a rarity. More common are parted fueling hoses and span wires, fouled screws, plus minor dents and scratches. Such tough lessons become legend amongst seafarers and we learned vicariously from these mistakes.

In operations, failure during replenishment at sea takes on a more serious nature. Less well known are replenishment events from the Second World War. Canadian escorts frequently had to abandon their convoys despite the presence of attacking U-boats, owing to the difficulty of mastering the intricacies of refueling at sea. At one point in the war, the Admiralty forbade Canadian warships from refueling in eastbound convoys due to the amount of damage they were doing to scarce replenishment equipment. A related problem arose during the Cuban Missile Crisis when returning Canadian warships had to pass right through their assigned anti-submarine patrol stations and carry on to Halifax to refuel. They returned days later. The accompanying aircraft carrier simply did not carry enough fuel to sustain her ‘thirsty’ escorts. Analysis showed that the navy needed a minimum of three replenishment ships to sustain short-range escorts at a distance of only 250 to 500 nautical miles from base.

Today, the Government of Canada has a penchant for deploying the RCN worldwide. The fuel capacity of our current frigates (.1 tonne of fuel per tonne of displacement) equals historic pre-war lows. This has forced planners to assume replenishment is a given in fleet operations. That assumption is now false. Without replenishment ships, the navy’s status has fallen and precious seamanship skills are wasting away.

Contracting foreign naval replenishment ships for short-term training is a necessary expedient but it is only a stopgap measure. It may be that Chantier Davie will be able to produce an interim solution in short order, but if it goes longer than six months you can expect the RCN to re-contract with the Spanish and Chileans on a regular basis.

The cost of leasing replenishment at sea services must now be added to the construction costs of the two new ships being built at Seaspan plus the cost of the building the interim ship by Chantier Davie. It should have been obvious that delaying the replacements for Protecteur and Preserver would result in added expense and more complexity in operations. It is a sad but entirely predictable mess and there is no real end in sight.

The blame for all this has to lay with the naval leadership. Somehow, generations of Canadian admirals decided that logistics is less important than combat capability. The National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS) is based on a one-for-one replacement plan of the Cold War Fleet, with the notable exception of the DeWolf-class arctic/offshore patrol ships. The logistical demands of this new security era are vastly greater than they were during the Cold War. The history of the RCN since 1989 has an abundant array of examples to prove this point.

I find it sad that the admirals care more about politics than they do about the history of their own service. A much more robust logistical capacity is needed immediately. They should remember this advice from American General Omar Bradley: “Amateurs talk tactics; professionals study logistics.”

Ken Hansen is an adjunct professor in graduate studies at Dalhousie University and a research fellow with the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies. He served for 33 years as a maritime surface warfare officer with the RCN. (Image courtesy of the Royal Canadian Navy.)