By Christopher Nelson

I recently had the chance to sit down and chat with Admiral Scott Swift, the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. In forty-five minutes we covered a range of topics, from leadership styles to discussions on risk, naval culture, and why he joined the U.S. Navy.

Sir, I’d like to start with a question about leadership. How would you describe your leadership style?

It’s an interesting question. I think if you want to understand my leadership style you have to ask a lot of other people. My experience is that when leaders are asked that question, they describe what they desire their leadership style to be as opposed to what it actually may be. But in a word, I would say the leadership style I try to emulate is to be inclusive. Leaders that I admire most are those leaders that have pursued an inclusive leadership style. As opposed to the opposite – an exclusive leadership style – one that excludes other opinions, one that excludes ideas that don’t match with their view of the world. Part of that inclusive leadership is uncertainty, it’s an important element. And it’s not something that is to be diminished but recognized and accounted for.

Anytime you are a leader in the military – or leader of any organization – there is more uncertainty than certainty in the decisions you face. And yet I struggled for a long time looking for words to describe that uncertainty in a broader context. Someone mentioned to me, actually they walked up to me and gave me a little piece of paper with a word written on it, and the word was “vulnerability.” I think as a leader it is important to be vulnerable. I don’t hear anyone saying that. Rather, I hear people saying to be a good leader it is about toughness, it’s about courage; it’s about being demonstrative and committed. I don’t see people saying it is really important as a leader to be vulnerable. Now, I don’t recommend that approach either, but in a discussion about leadership, I think it is important to tie that vulnerability into an element of inclusive leadership.

For example, I don’t like sitting at the head of the table. I sit here, on the side of the table during meetings. I do it on purpose because it makes the circle bigger. More people can talk when you are sitting in this chair directly across from you rather than sitting at the head of the table. This is especially true for the people envisioned as having the most power and that are most relevant are those that sit closest to the head of the table, as opposed to the tail of the table. So being inclusive, I think, is important. I’d like to think if you talked to 100 different people that know me, the majority would agree that my style is inclusive.

Are there are any people from your career or from history that you emulate, or that you think are great at inclusive leadership?

I think we are shaped by the time we are 16 years old. And I think the largest shaping element is our parents in those 16 years. I say 16 because by that time you start to think you are out from under that umbrella our parents provide. Then at about 18, you are really start transitioning out. So the transition occurs between 16 and 18. And of course, it could be grandparents or another individual that you may be drawn to that provides that guidance.

My experience, mainly from a discipline perspective, is when I get most insights into a Sailor’s background. I’ve seen wonderful Sailors come from wonderful parents; I’ve seen wonderful Sailors come from terrible parents, terrible Sailors from terrible parents, and terrible Sailors from wonderful parents. I think it is troublesome to try and correlate what happens in those 16 years.

The examples of leadership that are most compelling, those clearest to me, are examples of bad leadership. I had a tyrannical commander during one of my first tours. The squadron that I went to was the worst squadron on the base – everyone knew it and no one wanted to go there. But that’s where I ended up. I knew right away that I did not want to be a leader like that commanding officer. We thought the executive officer was exactly the same as the commanding officer because he was very loyal. He would say things like, “We need to support the CO.” But after the change of command, we realized he was a completely different leader. Two weeks later he was killed in an aircraft mishap. There was a direct input commanding officer that was put in that was just phenomenal, one of the best leaders I have ever worked with. But the leadership lessons that I got from him I never understood until, three, four, five years later. So the negative lessons are very clear in my mind.

The positive lessons are much more subtle. It goes back to what I learned from my parents, who had the largest influence on me. They were inclusive. And then I’ve had examples that have reinforced those experiences throughout my career.

Do you have any advice you would give to your younger self in the Navy? Any regrets?

I tell the same story all the time. I joined the Navy to get out of the Navy. I wanted to be an airline pilot. I couldn’t afford the certifications and the flight times that the airlines required. I joined the Navy because I wanted to fly, to get experience. At that time it was only a four-and-a-half year commitment from the time that you got your wings. And when my commitment was up, I was a week from leaving the Navy, I had all my paperwork, then I decided to pull my papers because I was afraid I couldn’t engender the same relationships outside the Navy as inside the Navy.

In fact, it’s funny, I know you’re familiar with Admiral Stavridis’ book The Accidental Admiral. I wanted to sue him for copyright infringement because I have been referring to myself as the accidental admiral for some time [laughter]. I made some comment to a group of people back when I was a one-star, and I would refer to myself as the accidental admiral, and I’d tell people that no one was more surprised than I was when I made admiral. And then afterward there would be a big line of people lined up, I assumed ready to congratulate me on these incredible statements I made. But no, they were there to tell me that they were more surprised than I was when I made admiral. My ego couldn’t take it anymore [laughter].

I think along with leadership there needs to be a true sense of humility. You shouldn’t feel worthy of the job. You should be made to feel unworthy because of the quality and commitment of the people around you. I was just up in the N37, the operations directorate. It is a small group of individuals, and it’s just incredible what they do. I don’t think they totally appreciate what they do and the impact of what their day-to-day actions are having on the Fleet.

It leads me to the direct answer to your question: I tell people that I owe the Navy everything and I owe the Navy nothing. I got in the Navy to get out, and here I am a four-star. I used to ask myself, “How in the heck did this happen?” Everybody else would say, “Yeah, I know, we are trying to figure out the same thing, so quit asking that question as well.” But at the same time, when I say I don’t owe the Navy anything, I’ve never done anything just to get a job. So my advice to people is, for example, if you really don’t want to go to Washington D.C. for a job, but you know it’s the best thing for your career, well, then don’t go. I’ve had three tours in Washington. D.C. I went back as the director of the Navy staff because the CNO said you have to come back to be the director because you don’t have a clue how the building works. I said, “Yeah, I don’t want to know how the building works” [laughter].

When I was a one-star I had a two-star come into my office. He was obviously down and wasn’t in that great of a mood. I said, “Hey, what’s up?” He said, “I just found out I’m going to this job.” I said, “I would love to go to that job. So where’s the bad news in this?” His comment was that no one that went to that job was promoted to a three-star. So, here I am a one-star, and this guy’s a two-star, and he’s worried about making his third star? He was worried about all the wrong things. The job he was offered was a great job that would have opened all types of doors inside and outside the military.

I have no regrets. I always viewed every set of orders that I got as an opportunity.

A friend of mine once told me that he tries to balance work, family, and faith. I’ve seen your schedule, you are incredibly busy. How do you balance your work and family life?

When I was an O5, I was spending way too much time with work and not enough time with family. So we took a day out of the weekend and said this day is for us. We weren’t going to do anything that I didn’t want to do, and we weren’t going to do anything my wife didn’t want to do. We’d pick a day, a Saturday or a Sunday. The first day I grabbed a bucket sitting out in the garage, and she asked, “What are you doing?” I said, “Well, this is our day together.” “I know,” she said, but “what are you doing?” I said, “I’m going to wash your car.” She then said, “That’s what you want to do, I don’t care what my car looks like.” Even then I was still too focused on the stuff that needed to get done. I have a hard time relaxing. That lasted for that tour and it lasted through my major command tour. Once I made flag officer it went out the window.

So what we do now is on Saturday and Sunday morning we don’t set the alarm; we wake up when we wake up. We go downstairs and have a cup of coffee and sit in the living room and just talk about whatever is on our minds. It might be ten minutes or it might be two hours. Whenever work intrudes I have to go off and do the work thing. We go out on Saturday to either lunch or dinner. And then on Sunday, we’ll go out to lunch. My Sunday afternoon is committed to getting ramped back up for the week. Then one week out of the quarter I take leave. My wife said we can’t spend our leave on Oahu, we have to get off the island because work is always there. So I said, “How about the big island, you know, for distance?” She said, “Yeah, that would work.” I thought: that was too easy. So we started planning our first trip. I said to her, “You said the big island was OK, so are you thinking about Kona?” She then said, “No, no, I meant the big island – California or east.” That was a wakeup call [laughter]. But you have to find that time for yourself. It’s a sacrifice. You have to have the humility to ask yourself what are the things we need to do together.

There’s a saying that a chaplain whispered in my ear as a reminder when I was talking to the Sailors at the Fitzgerald memorial, and I think it is originally a Morale, Welfare, Recreation (MWR) saying, but it’s “Mission First, Sailors Always.” I always thought that was backward. I changed it when I was a strike group commander. What I said was “Sailors First, Mission Always.” And then I changed it from “sailors” to “people.” So now what I say is “People First, Mission Always.” Because if you put the mission first there is never time for people. The mission will just consume all the energy and all the resources that you have. Show me a mission you can get done without people. If you focus on the people they’re going to get the mission done. People naturally gravitate toward getting the mission done. They don’t gravitate towards spending more time with their family. That’s the message we have to drive through – the idea that you have to make time for you and your family.

I thought this was going to be a two-year tour, but when I found out this was going to be a three-year tour, I knew I had to make a change. When the CNO told me it was going to be three years, I sat down with my wife the next morning. I found out on a Friday, and that next morning, that Saturday, it impacted me and my wife the same way. Both of us knew we would have to change our lifestyle. We knew we had to take measured time off; we came to this conclusion independently.

Sir, I want to shift the conversation to risk. And the anecdote that is often used as a comparison between today’s Navy and the Navy of the early 20th century is Admiral Nimitz grounding his ship, the USS Decatur, when he was an ensign. He turned out OK, even though he was court martialed and received a letter of reprimand. Behind this anecdote is the idea that years ago we would accept more risk and failures were forgiven. But today we simply don’t. Do you agree with that? Are we a risk averse Navy? Do we know how to fail and allow ourselves to learn from those failures?

Yes. I think we are a risk averse Navy and, not only that, a risk averse society. I think it is driven by a few things. 9/11 has something to do with it as does the numerous bombings and terrorist attacks over the years. Parents are nervous about where their kids are, and so on. I used to take off out of the house when I was a five year old. I was well beyond the confines of what my parents thought the neighborhood was. I didn’t give it a second thought; my parents didn’t give it a second thought. And I would be much more concerned about my kids doing that today after reading all these reports in the paper about crimes.

So I don’t think the risk is any higher today, however, we are more informed as a society today, and because we are more informed we tend to be less tolerant. We are less tolerant of making mistakes. And unfortunately, the by-product of that is we are less tolerant of learning. In my mind we are caught in this loop: we don’t want to learn by making mistakes, so we have more mistakes, more mishaps. We try to manage risk directly as opposed to saying, as an example, letting a young child explore the world and make mistakes, it’s part of life’s learning. I think that’s true in the military. We do need to be more tolerant of risk. There need to be fewer implications with respect to making mistakes. And I mean regimented implications. You need to study each mishap as being unique. And then from what you learn you need to decide what measures need to be taken to prevent it from happening again.

Do you think this discussion about risk will be one of the biggest challenges the Navy will face in the next 5-10 years?

I don’t know if it will be the biggest challenge, but it is a challenge the Navy needs to take on. And its a culture change, so it is going to take a long time.

The culture we need to change in the Navy is a 20-year culture. People that are going to leave before retirement, those people will be hard to change. The most compelling group to change is the group that is going to stay for 20 years. If you are trying to influence a group that has a 20-year lifespan within the organization, you’ve got to force the change as a commander and hold that change “lever” for 10 years. If you want to move the culture, and you hold that lever over, after 10 years, when you let go of the lever, it’s going to go to the middle. Half the people are used to where you held the new culture at, the other half remember how it was. And that half that remembered what it used to be like…well, they don’t like change, they don’t like uncertainty, they like that stability. They don’t like all of those elements that we characterize as risk.

Risk aversion is part of our society – certainly the world and American society – and it’s part of our Navy. I think the experiences of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom were incredibly resourced from a financial and manpower perspective, so commanders drove risk to zero. We are not going to have those kinds of resources to face our future threats.

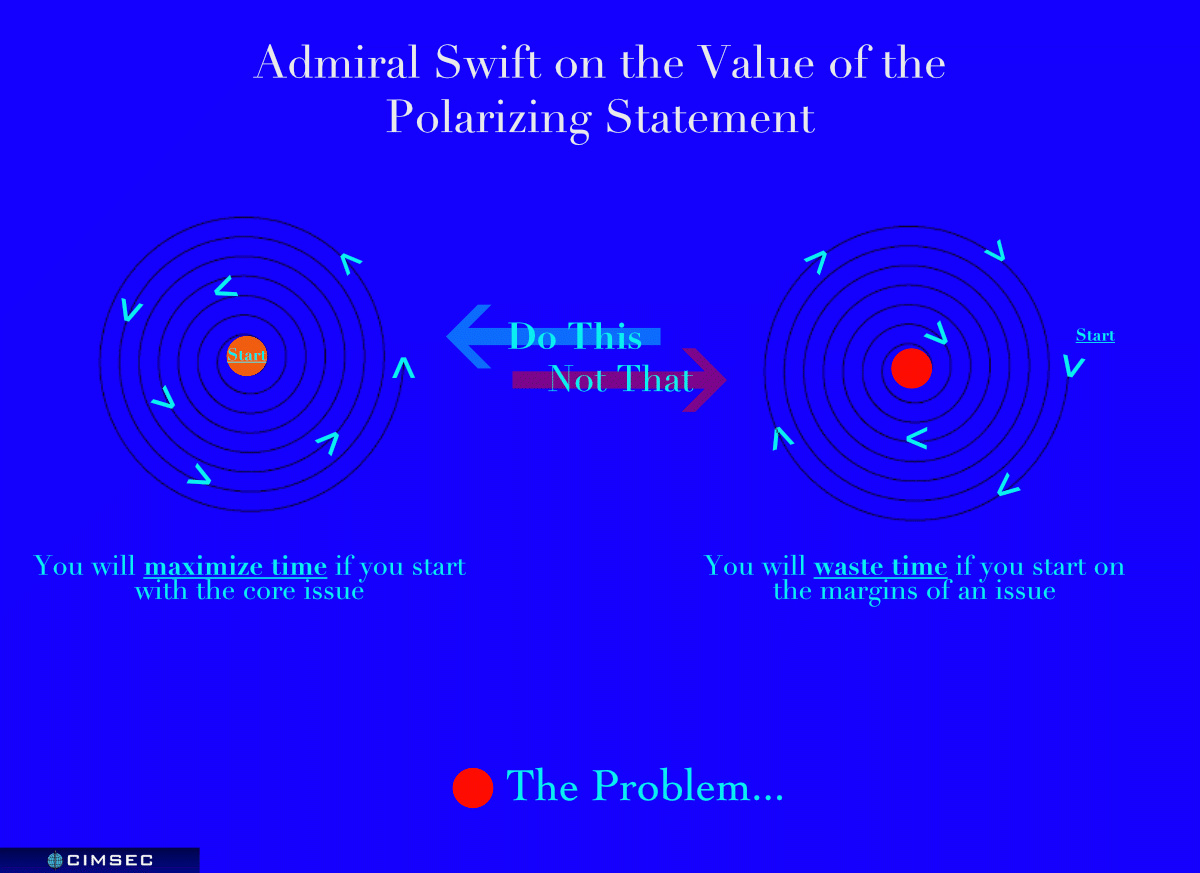

On the staff, we talk about how you like to say a polarizing statement, particularly in a brief or a small group discussion. Is there a reason why you use the polarizing statement?

Time. My most precious personal resource that I have is time. My most important professional resource is people. This is the danger of being inclusive. You can’t just sit around and have the big long conversation. That’s not what being inclusive is about. What’s being inclusive is the diversity of the group as well. You need to have a diverse staff. It’s not gender diversity, it’s not racial diversity, it’s none of those things – it’s the diversity of ideas. We get to a diversity of ideas by seeking to include people within our spheres of leadership and organization that have had different life experiences than us. And we have to value them for those experiences, for who they are.

That is why I seek to surround myself with people whose life experiences are different than mine. Who are not white males, from southern California, who went to OCS, and flew jets. Otherwise, we end up as a group-think organization. But if you don’t create an inclusive environment, no one is going to bring those ideas in. So if you don’t sit here at the table and invite people to put all their ideas on the table and then criticize the ideas without criticizing the individual – that’s what’s being inclusive. But that takes time. To optimize the time I want to keep the dialogue going.

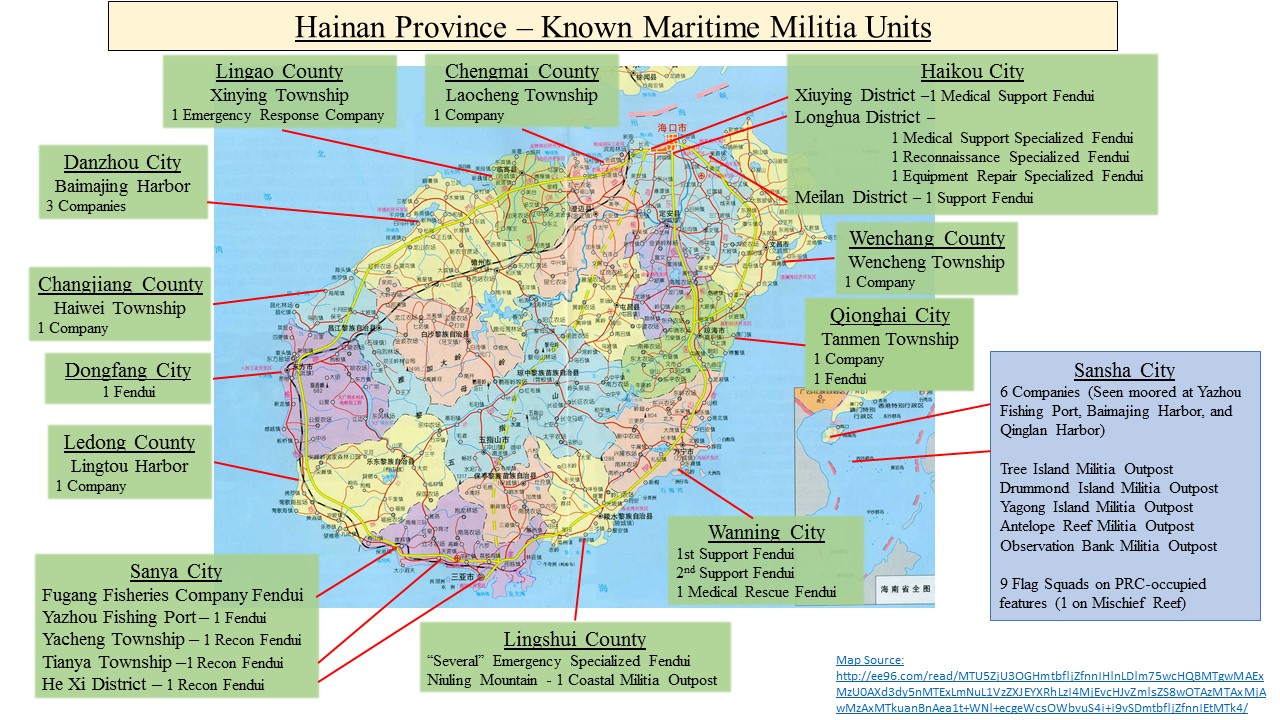

If we start out on the margins of the issue, circling around until we finally get to the core issue, and it takes twenty minutes, we’ve just wasted twenty minutes. So if that is what the discussion should be about, well, put that on the table. This is what the discussion is, and drive the discussion out in an increasing circle from there. This additional discussion can happen after you have that polarizing statement. [FIG 1.]

The other reason is, in order to be inclusive, people have to be willing to put their ideas on the table. I need to be willing to my put my ideas on the table and have people critique them, just like anybody else. So, who has the better idea, me or you?

It depends on the topic and the person’s expertise.

Absolutely. But I’ve got this bubble around me. People think that because I have four stars that somehow I am intellectually superior to them. That’s not the case. You’ve got to empower the group. That’s not a common response. That’s the response of someone that has been inculcated in an inclusive learning environment, in an inclusive leadership environment. So let’s have the polarizing statement first so we know what the goal is, and then people can say, “I don’t think that is central to the discussion.” Yes, the issue may be somewhere else. And I reserve the right to change my mind. Here’s what I think today, ten minutes later I might have a different thought. Leading is listening; it’s not transmitting, it’s not one-way communication.

Sir, to be fair, as a four star when you change your mind, it has reverberations. Do you realize the unintended effects it may have on the staff?

You have to be careful with what you say. Sometimes I don’t appreciate that enough. The best rank that I ever had was lieutenant. I had more authorities, more insights, and more knowledge about my specific weapon system. And I could get more things done as a lieutenant. But now that I am a four star, yes, I can get specific things done by throwing my weight into it, but I still think of myself as a lieutenant.

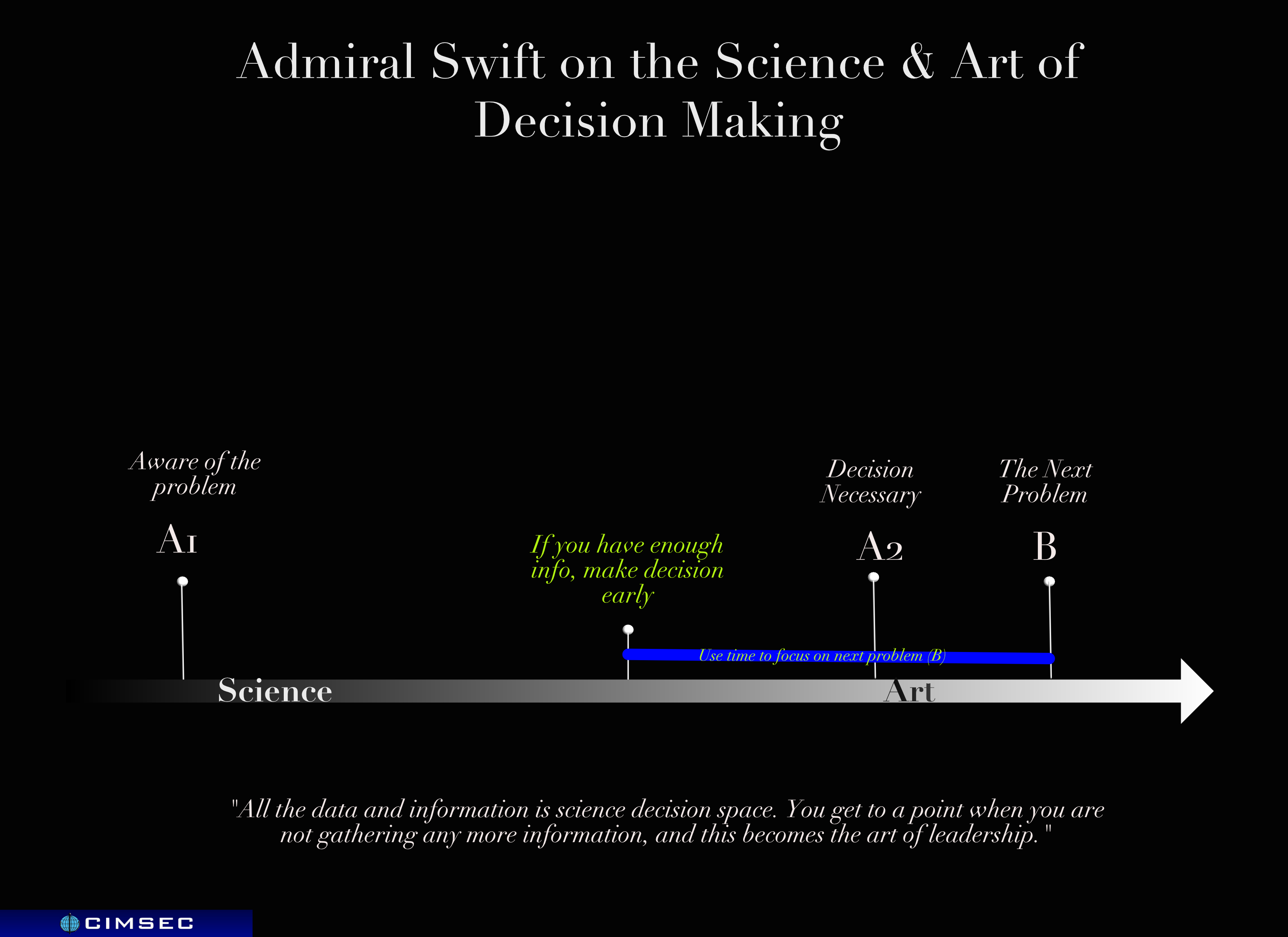

Whenever I say something about work, my wife always says, “Here we go again, the staff is going to jump through hoops, they are going try and deliver on that.” She’s right. It’s just a comment that I make, so it does have an impact. In answer to your question: We should delay decisions until two points. One point is when you determine no more information is going to come into the situation, and then move on.

If this is when you are aware of the problem, here (A1), and this is when the decision needs to be made (A2). You should not make a decision until this point unless you have sufficient information to make the decision earlier. If you do have that information, well, then make this decision at this point and give all this time back to others to focus on other things, then we are done with problem A. We’ve made a decision here, now let’s move on to the next problem which is problem B.

So now this is problem B solving time. You may get to the point where you don’t have enough information to make the decision, that’s when you go to the commander, and the commander says this is what we are going to do. The first decision point is when you have the knowledge to make an informed decision, the second decision point is when you have to actually make the decision.

Commanders lose sight of this because they want all the power that comes with the authority of command, but they don’t want the responsibility. Well, then why did you make that decision? I didn’t have enough information to make an informed decision, so I made an uninformed decision. How many people are willing to say that? That’s what command is. Nimitz made uninformed decisions all the time. The decision Nimitz made for the Coral Sea was absolutely uninformed. It was subjective. So we talk about the science of leadership and we talk about the art of leadership.

All the data and information is science decision space. You get to a point when you are not gathering any more information, and this becomes the art of leadership.

What’s the last good book you read?

It won’t surprise you, you’ve read it, but it’s Jim Hornfischer’s Neptune’s Inferno. There’s a whole raft of reasons why that book is compelling. It’s a book on the science of leadership and the art of leadership. It’s also easy to read. If I can’t figure out where the author is going on a subject within the first thirty pages, then it is difficult for me to continue with a book because rarely do I have the time.

It is a compelling book because it gets at a strategic dichotomy between the Marine Corps and the Navy. It’s compelling from a leadership perspective, with Admiral Ghormley being stuck behind his desk and not being able to circulate through the battlefield. And the tyranny of distance – the Nimitz picture with the HF radio in the background – he’d listen to the communications and through those comms, he would try to patch together what was going on. He knew he had a problem with Ghormley, but he couldn’t figure out exactly what it was. It took him three months to come to the decision that he had to relieve Ghormley to get the campaign moving forward. So he had a decision to make: do I send Halsey or do I send Spruance? I like Spruance because I am a believer in inclusive leadership. (And another great book is The Quiet Warrior, by Buell. I am attracted to Spruance, so that is not an unbiased recommendation. I’ve read it several times.)

So Nimitz decided to send Halsey down there because he needed someone to kick ass. He didn’t need a lot of theory applied; he needed a bunch of ass kicking, someone to get it done. That to me is compelling from a leadership perspective. That comes out in Neptune’s Inferno.

And then the technical piece is interesting. We had some young lieutenants that were involved in the design process of radars. They were providing advice to the task group commanders on how to use radar. But the task group commanders were putting the radar ships in trail. Information was the key to night fighting. So the radar pickets should have been up forward to give a better sense of what the Japanese were doing. So we’ve got this technology piece which is a lesson as well. I’m a big believer in the Third Offset strategy, but I’m concerned we are going too far to technology as being the solution. The most critical weapon system that we own in the U.S. military is something that we all carry with us all the time – it is right between our ears. That’s what we need to get focused on. That’s why that book resonates with me.

Along these lines, where do you go for your news? How do you consume daily news media?

I asked my PAO if there was a program out there that could sort through news and blogs. And I’ve found a news app, and I do a lot of reading with that application. But you have to be careful with an application like that because you tend to self-select stuff. So if you read stuff that you agree with you are reinforcing your own ideas. So you need diversity. And I don’t have a favorite news channel. I view all channels regardless of my personal view. You have to have alternate views, and you are not going to get them if you go single source. All of my personal reading is actually professionally based.

Last question, what advice would you give to the next Pacific Fleet Commander?

Having that sense that there are going to be good people there, that they will help you through this process, is the advice that I would give. You need time ahead of the turnover to circulate through the staff to get a sense of what is going on. And you need time after turning over to circulate through the staff. After I took this job, a month was set aside for what I call listening. Another month was set aside for observing, and a third month was set aside for acting. The pass-downs are easier the more senior we get. The pass-down I got when I was the coffee mess officer as an ensign, well, that was a lot of accounting. The pass-down as the security officer as a lieutenant, that was a pain, no one had done an inventory for over two years. I was like “what!” Tracking down all the stuff that had been destroyed or not, that was hard.

This job, you know what the science is, the hard part is understanding what the art is. What are the personalities? Surveys are important here because it will help you understand where we are as a staff. That’s how I determine if we are making a difference. Do people feel empowered? Are they excited about coming to work?

Sir, thank you for the time. I enjoyed it.

Thanks for all you do.

Admiral Scott Swift was promoted to Admiral and assumed command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet on May 27, 2015. He is the 35th commander since the Fleet was established in February 1941 with headquarters at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Read his entire bio here.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson is a naval officer stationed at the Pacific Fleet Headquarters in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Navy’s Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, RI. The comments and questions here are his own and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

Featured Image: U.S. Navy Adm. Scott H. Swift delivers remarks as he assumes command of U.S. Pacific Fleet from Navy Adm. Harry B. Harris Jr. during the change-of-command ceremonies for U.S. Pacific Command and U.S. Pacific Fleet in Honolulu May 27, 2015. (U.S. DoD)