By Chad Pillai

There is a growing strategic competition underway in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea between India and China focused on acquiring commercial ports and military facilities. It is a race for strategic access, leverage, and influence for energy resources, markets, and national security. This competition between two relative new naval powers in the region will directly influence the U.S. and its regional partners in the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) and U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) Area of Responsibilities (AORs), beyond the usual purview of Pacific Command (USPACOM) whose AOR India lies within. For the U.S., this represents a strategic opportunity to compete against China’s growing influence by expanding its relationship with India in the CENTCOM and AFRICOM AORs.

Nyshka Chandran reported on CNBC in February 2018 that “China and India are competing for regional supremacy in the Indian Ocean as they look establish a stronger military and economic presence in bordering countries.” China’s move into the Indian Ocean, as part of its “String of Pearls” approach to expand its strategic reach, is well documented. The formal establishment of China’s first overseas military base in Djibouti serves as its first military marker on the global map. Recently, China has been in negotiations with Pakistan to expand its access to the port of Gwadar and open its second overseas naval base in Jiwani, Pakistan which is about 80 km from Gwadar. These two locations would provide China the means and proximity to militarily influence two of the world’s eight strategic chokepoints, the Bab el-Mandeb straits along at the mouth of the Red Sea and the Strait of Hormuz. Additionally, China has been expanding its economic presence in the Seychelles, Maldives, and in Oman.

While China expands its presence, India has not remained idle. It has invested in the commercial port of Chabahar, Iran to give it greater access to Afghanistan, circumventing Pakistan. However, questions arise on whether India can use the port to effectively compete against China and its One Belt and One Road (OBOR) strategy. In addition to the port in Iran, India is competing for access to the Seychelles, Maldives, and Oman. The recent tensions between China and India, after China deployed 11 warships to the Maldives in February illustrates this growing rivalry. In the Seychelles, India is spending $46 million dollars in foreign aid to improve costal defense and airstrips; however, that has run into recent issues with the president of the Seychelles. While India doesn’t lack in its ambition to compete with China, it lacks a cohesive political and economic decisionmaking body like China to invest and outcompete, and lacks in its naval capabilities to effectively challenge the Chinese. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), China’s naval surface combatants dwarfs India (83 Chinese combatants vs. 27 Indian Combatants; 57 Chinese attack submarines vs. 15 Indian attack submarines; and 4 Chinese ballistic submarines vs. 1 Indian in development). Of course, the naval disparity between the two nations is spread out across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and China must overcome its “Malacca Straits Dilemma” to surge forces into the Indian Ocean.

This growing competition between China and India present a strategic opportunity for the U.S. to offset China’s growing presence in the region. While the U.S. has generally viewed India as a strategic partner in the U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) AOR to offset China, it represents an opportunity to counter-balance China in the USCENTCOM and AFRICOM AOR as well. In concerted effort by USCENTCOM, in partnership with PACOM, can find ways to enhance the Indian Navy’s force projection capabilities in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea to challenge China’s small, but growing, military presence in the region. U.S. Navy Central Command (USNAVCENT) can spearhead this effort on behalf of CENTCOM by encouraging India to more fully participate in the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) that focuses on Counter-Piracy operations. NAVCENT could consider future joint naval exercises focusing on combined naval operations, Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW), and carrier-based operations. Such combined exercises can assist India in expanding its capabilities and capacity to exert greater influence, in concert with U.S. interests, in the region as a means to counter-balance China’s presence. Additionally, as Harry Halem recently noted, the U.S. can encourage greater cooperation between its allies and partners in the region, to include Israel, to cooperate with India. This also includes expanding ongoing Indian-French naval cooperation in the Indian Ocean as seen by France’s deployment of its Charles De Gaulle strike group to exercise with the Indian Navy. For the U.S., these efforts will have to be delicately balanced with the U.S. relationship with Pakistan and it may raise concerns on the Pakistani Navy’s ability to counter-balance India as well.

Increased ties between the U.S. and India will also support increased foreign military sales of U.S. capabilities. Recently, the U.S. has become one of India’s primary weapons exporters with sales of “Boeing P-8I Neptune — a version of the U.S. Navy’s P-8 Poseidon anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft.” Additionally, the U.S. offered to sell its Harpoon missile to India. The recent cancellation of the Indian-Russian Stealth Fighter presents an opportunity for the U.S. to offer its platforms to include the F/A-18 Super Hornet. An area of future opportunity may lie in a combined shipbuilding program to assist the Indian Navy in its modernization efforts. These sales will contribute towards developing increased interoperability between the U.S. and Indian Navies, along with allied and partner navies in the region.

While China is attempting to build upon the legacy of Zheng He (Ming Dynasty), India must learn to use its geographic positional advantage in the Indian Ocean that dominates east to west maritime traffic. The key to leveraging its geographic positional advantage in the Great Game of the Indian Ocean will be based on a mutual desire by India to expand its military, primarily naval, capabilities to compete with China and, a mutual desire by the U.S. and India to expand their military cooperation. For the U.S., India can no longer be viewed simply as a PACOM partner. Instead, it must be viewed as a trans-regional partner who has the ability to influence both the CENTCOM and AFRICOM AORs as a counter-balance to China’s growing global ambition. As Robert Kaplan, author of Monsoon, has noted, the Indian Ocean represents the fulcrum between American Power in the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific, and its growing relationship with India will shape its desire to remain atop the global order against a rising China.

Chad M. Pillai is an experienced Army strategist and is a member of the Military Writers’ Guild, Army Strategy Association, and contributes to the U.S. Naval Institute. He has operational experience in the CENTCOM AOR and has traveled to India, to include 1998 during the Indian and Pakistani nuclear tests of 1998. He received a Masters in International Public Policy from the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). The article reflects the opinion of the author and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Government and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Featured Image: SASEBO, Japan (June 10, 2016) – Rear Adm. Brian Hurley, center, deputy commander, U.S. 7th Fleet, tours the Indian navy Kora-class corvette INS Kirch (P62) during Malabar 2016. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Ryan J. Batchelder/Released)

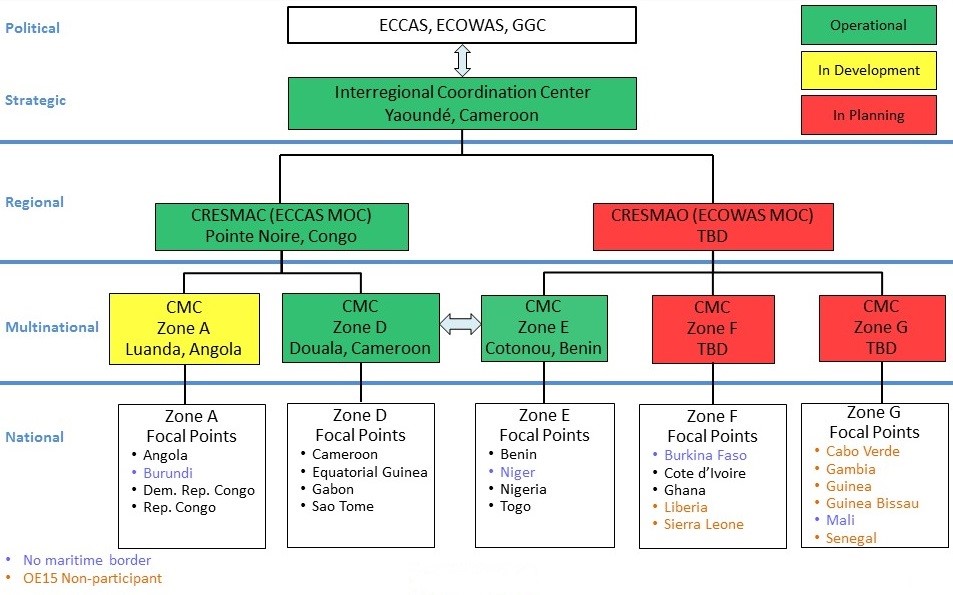

We interview CAPT Rinko, USN, and CDR Sune, Cameroon, about Obangame Express, the 23 Nation Gulf of Guinea Maritime Security exercise. We discuss the scope and purpose of the exercise, the challenges of building cross-organizational/ cultural/ national inter-operability, and lessons learned. For context on the ongoing expansion and conduct of Obangame Express,

We interview CAPT Rinko, USN, and CDR Sune, Cameroon, about Obangame Express, the 23 Nation Gulf of Guinea Maritime Security exercise. We discuss the scope and purpose of the exercise, the challenges of building cross-organizational/ cultural/ national inter-operability, and lessons learned. For context on the ongoing expansion and conduct of Obangame Express,