This article is part of a series that will explore the use and legal issues surrounding military zones employed during peace and war to control the entry, exit, and activities of forces operating in these zones. These works build on the previous Maritime Operational Zones Manual published by the Stockton Center for International Law predecessor’s, the International Law Department, of the U.S. Naval War College. A new Maritime Operational Zones Manual is forthcoming.

By LtCol Brent Stricker

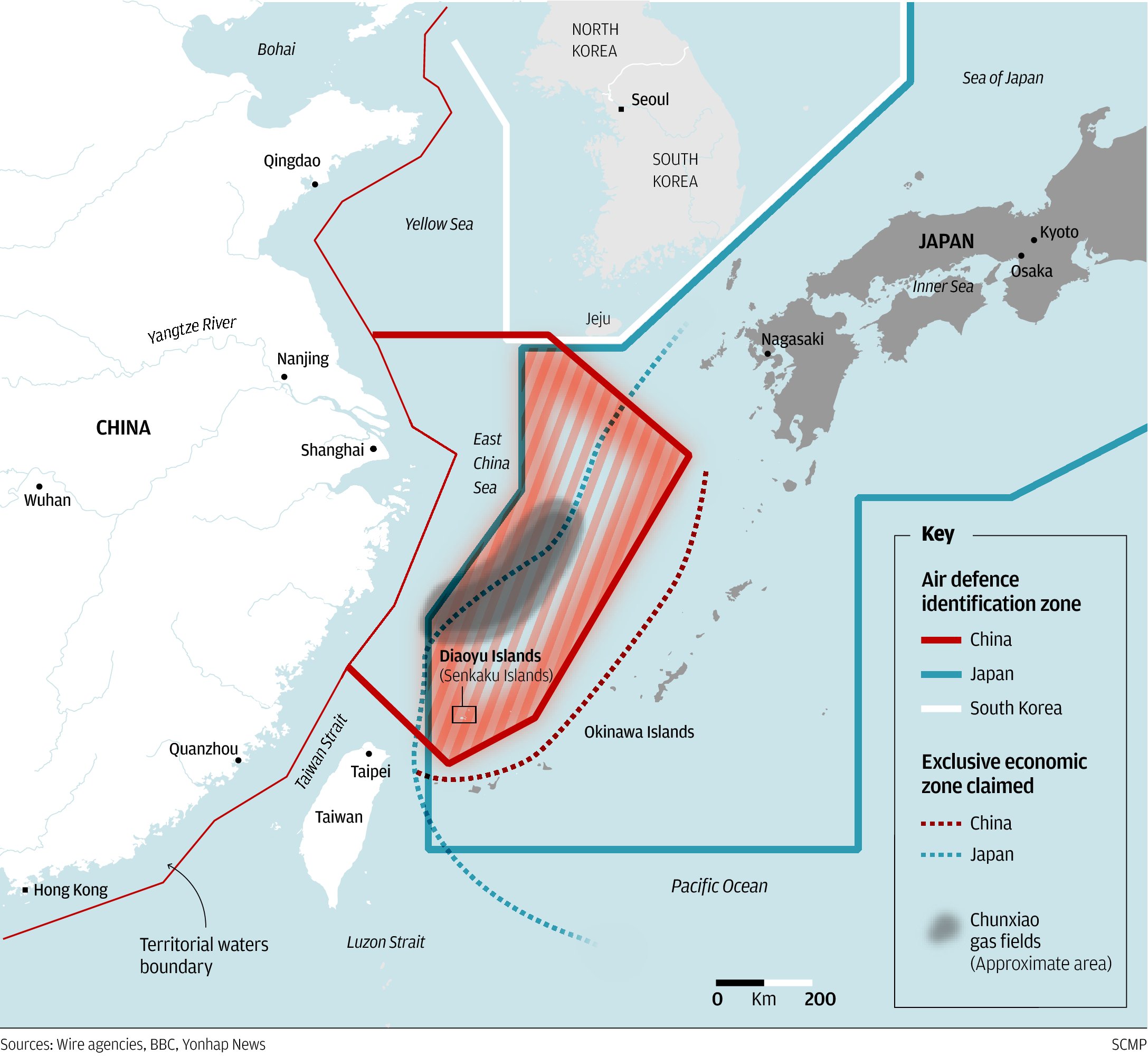

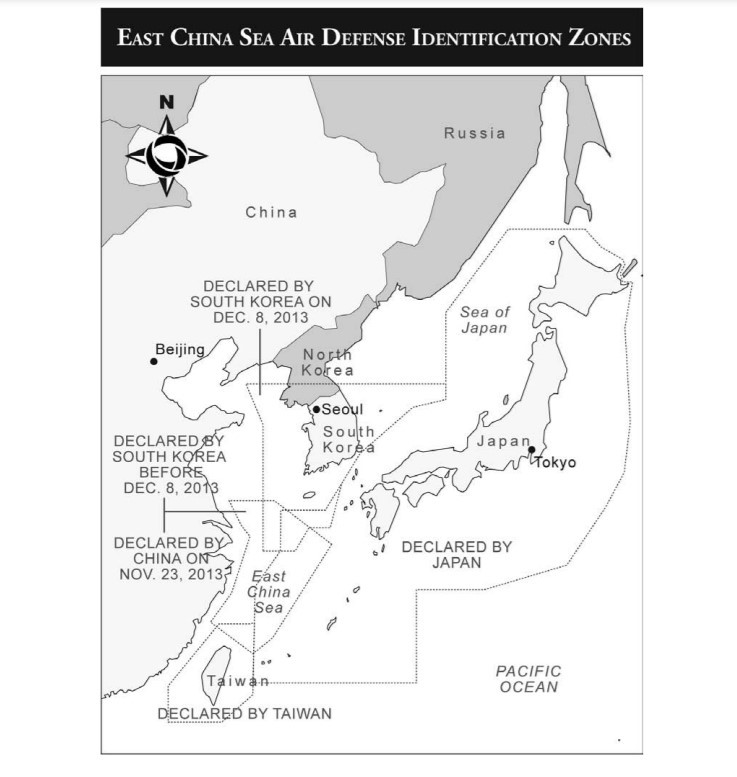

Tensions could be high in East Asia when a civil aircraft flying in international airspace over the East China Sea (ECS) finds itself intercepted by military fighter aircraft. These aircraft are part of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) system which exists to identify and control aircraft approaching a nation’s airspace. Intercepted aircraft can be ordered to land in a country they never intended to visit, shot down for failure to comply, or perhaps suffer a mid-air collision as occurred in the EP-3 incident. Unfortunately in the ECS, there are four overlapping ADIZs (Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan) increasing the risk for civil aircraft navigating the area.

The patchwork of overlapping Air Defense Identification Zones (ADIZs) covering much of the East China Sea represents a potential flashpoint for conflict. A brief survey of the history, purpose, and location of these zones can help frame these risks for the future.

A Short History of the ADIZ

International law governing aircraft evolved after the First World War with the adoption of the 1919 Paris Convention for the Regulation of Aerial Navigation.1 The Paris Convention treated international air space like the high seas, adopting the principle of caelum liberum (freedom of the skies) where national sovereignty could not be asserted.2 The Paris Convention was replaced by the 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation (Chicago Convention). The Chicago Convention maintains the distinction between national and international airspace but only applies to civil aircraft.3 State aircraft, which include military, customs, and police aircraft, are exempt from compliance with the convention but must operate with “due regard” for the safety of civil aircraft and may not fly over the territory, including the territorial sea, of or land in another state without permission.4

An Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) is defined in Annex 15 of the Chicago Convention as a “Special designated airspace of defined dimensions within which aircraft are required to comply with special identification and/or reporting procedures additional to those related to the provision of air traffic services (ATS).”5 Information regarding the establishment of ADIZs and their reporting requirements is available in each states’ Aviation Information Publication.6

The United States pioneered this concept by creating the first ADIZ in 1950 and encouraging its allies, such as Norway, Iceland, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, to establish similar zones. An ADIZ can extend beyond national air space into international airspace to allow states to identify aircraft approaching their territory to ensure they are not a hostile threat. ADIZ reporting requirements vary by state, but all have requirements to identify approaching aircraft and their origin and destination. An ADIZ is analogous to port entry requirements or conditions a state imposes on ships entering or transiting its internal waters.7 Since the end of the Cold War, ADIZs have declined in use. Norway and Iceland’s ADIZs, for example, were decommissioned after the Cold War ended.8

While states exercise sovereignty over their national airspace, an ADIZ that extends beyond a state’s territorial sea only allows the state to establish “conditions and procedures for entry into its national airspace.”9 These conditions and procedures may include filing a flight plan before departure, aircraft identification requirements, and positional updates.10 Aircraft entering an ADIZ that do not intend to enter national airspace continue to enjoy high seas freedoms of overflight and are not required to comply with ADIZ requirements.11

A civil aircraft entering an ADIZ that fails to comply with the conditions and procedures for entry into national airspace may be considered a potential threat. Typically, such non-compliant aircraft are intercepted by military aircraft to determine their intentions. Violation of ADIZ requirements does not, however, authorize a military aircraft to attack a civil aircraft unless it commits a hostile act or demonstrates hostile intent.12 For example, in February 1961, a Soviet state aircraft was flying in international airspace over the Mediterranean Sea 80 miles off the coast of French Algeria when it was intercepted by a French fighter.13 The French claimed that the aircraft had entered a declared “zone of identification,” had diverted from its declared flight path, and was approaching Algeria without responding to radio challenges.14 Although only warning shots were fired, the diplomatic fallout of the incident was a recognition by both the Eastern and Western powers that there was a free right to navigation in international airspace even within an ADIZ.15

East China Sea ADIZ

ADIZs have been established in North Asia by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. The PRC ADIZ differs from the others in that it intentionally overlaps portions of the other three. The PRC ADIZ also includes the airspace above Japanese administered territory16 and appears to assert jurisdiction over international air space.17 (The People’s Republic of China AIP can be accessed here.)18

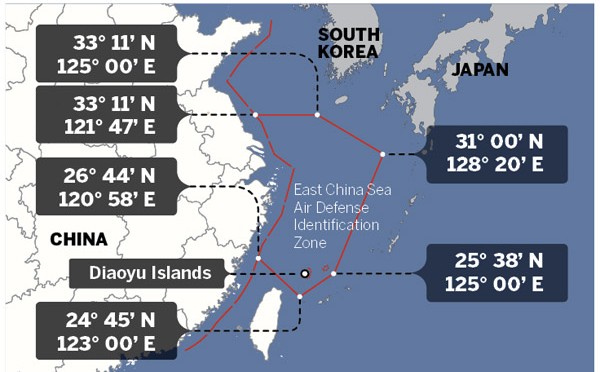

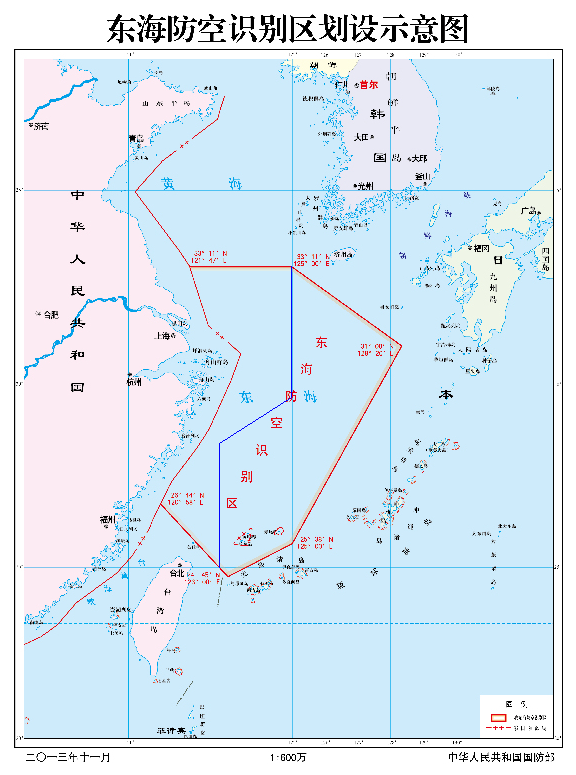

The PRC declared an ADIZ in the East China Sea on November 23, 2013.19 This ADIZ differs from other zones because claims to apply to all aircraft transiting the zone whether or not they intend to enter PRC national airspace. Such a requirement is inconsistent with international law.20 The zone requires all aircraft transiting through the zone “to follow identification rules, including filing a flight plan with the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs or Civil Aviation Administration; maintaining two-way radio communications and responding promptly to identification requests from the Ministry of National Defense; operating a secondary radar responder (if equipped); and marking nationalities and logos clearly.”21 The zone therefore illegally purports to assert PRC jurisdiction over aircraft in international airspace.22 Under international law, all transiting aircraft are guaranteed freedom of overflight in international airspace seaward of the territorial sea.

The PRC zone directly overlaps with those of Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan.23 This was the first ADIZ to intentionally overlap with another.24 It also includes airspace over the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands adjacent to Taiwan. These islands are the subject of a territorial dispute between the PRC/Taiwan and Japan.25

Both the United States and Japan protested the establishment of the ECS ADIZ. Then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry accused China of attempting to change the status quo in the East China Sea and increasing tensions in the region. The U.S. statement further indicated that the United States does not “support efforts by any state to apply its ADIZ procedures to foreign aircraft not intending to enter its national airspace.” Japan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs similarly accused China of attempting to change the status quo in the East China Sea, indicating that the ADIZ “measures unduly infringe the freedom of flight in international airspace…and will have serious impacts on the order of international aviation.” Japan also objected strongly to the inclusion of the airspace over the Senkaku Islands within the ECS ADIZ.

| Name

Lateral Limits |

Upper/Lower Limits and system/means of activation announcement INFO for CIV FLT |

| 1 | 2 |

| PRC ADIZ

3º11’N and 121º47’E , 33º11’N and 125º00’E, 31º00’N and 128º20’E, 25º38’N and 125º00’E, 24º45’N and 123º00’E, 26º44’N and 120º58’E |

UNL / SFC |

Taiwan’s ADIZ is defined in its AIP.26 The Taiwan ADIZ was established by the United States after the Second World War and applies the standard request for aircraft entering the zone intending to enter Taiwanese air space to identify themselves. Civil aircraft are required to fly above 4,000 feet along designated airways or as vectored by air traffic controllers. Aircraft that do not comply with these requirements are subject to intercept by military aircraft.27 Other examples for intercept include, “Aircraft deviat[ing] from the current flight plan – fail[uire] to pass over a compulsory reporting point within 5 minutes of the estimated time over that point; deviat[ing] 20 NM from the centerline of the airway; or 2000FT difference from the assigned altitude; or any other deviations.”28 Taiwan’s AIP publishes strict guidance for aircraft to “fly straight and level” upon interception and to take no action that might be viewed as hostile. Communication with the intruding aircraft will be attempted via radio or visual signals. The AIP notes that Taiwan will not be held responsible for damages caused by interception or failure to comply with ADIZ requirements. Since September 2020, Chinese military aircraft have maintained a near continuous presence in the Taiwan ADIZ, penetrating the zone nearly 2,200 times. Although China believes that these incursions are consistent with international law because Taiwan is part of China, Taiwan has stated that it will respond in self-defense if attacked.

| Name

Lateral Limits |

Upper/Lower Limits and system/means of activation announcement INFO for CIV FLT |

| 1 | 2 |

| Taiwan ADIZ 210000N 1173000E – 210000N 1213000E – 223000N 1230000E – 290000N 1230000E – 290000N 1173000E – 210000N 1173000E. |

UNL / SFC |

The South Korean ADIZ is described in its AIP.29 The ADIZ was established in 1951 by the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War. It currently includes airspace above Ieodo/Suyan, a submerged feature disputed between South Korea and the PRC. South Korea expanded its ADIZ to include the airspace over Ieodo in December 2013 after the PRC included the airspace above the feature in its ADIZ in November 2013.30 The Korean ADIZ is similar to the PRC ADIZ in that it requires aircraft flying in the zone to submit a flight plan whether or not they intend to enter Korean air space. Aircraft are required to maintain two-way radio contact, use a secondary surveillance radar transponder, and make position reports every thirty minutes to air traffic control.

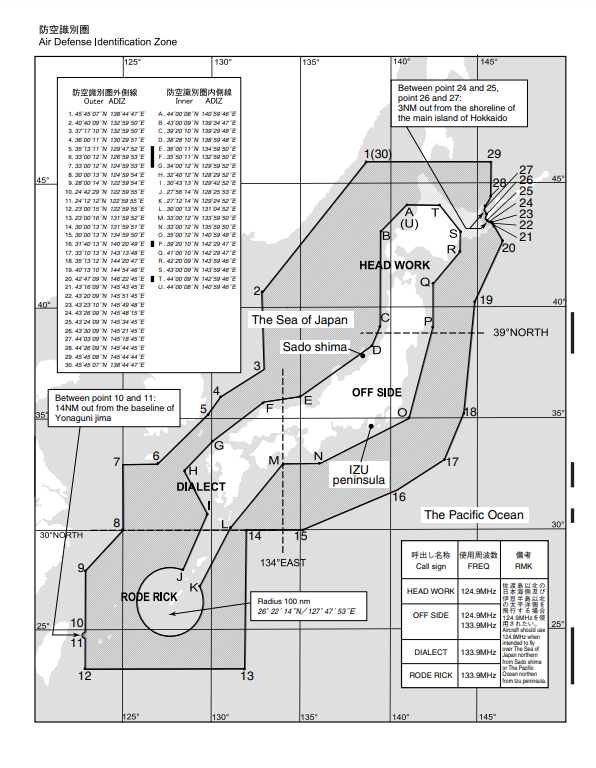

An illustration of Japan’s ADIZ is contained in its AIP.31 Japan’s ADIZ was established in 1969. It does not include the airspace above the disputed Northern Territories/Kuril Islands controlled by Russia.32 The Japanese ADIZ follows the North American example applying its procedures only to aircraft intending to enter Japanese national airspace. The zone is divided into an inner and outer zone. The inner zone overlaps the territorial Sea of Japan. An aircraft entering the inner zone is expected to file a flight plan in advance and comply with air traffic control instructions or face interception.

| Name and lateral limits | Upper limit / Lower limit |

| 1 | 2 |

| KOREA ADIZ(KADIZ)

3900N 12330E – 3900N 13300E- 3717N 13300E – 3600N 13030E- 3513N 12948E – 3443N 12909E- 3417N 12852E – 3230N 12730E- 3230N 12650E – 3000N 12525E- 3000N 12400E – 3700N 12400E- 3900N 12330E |

UNL/SFC |

Conclusion

While ADIZs may have once been a relic of the Cold War, the situation in the East China Sea has seen an increase in their use. As the issue of China-Taiwan relations remains unresolved, the PRC ADIZ might become a tool to pressure other nations if the PRC chooses to assert sovereignty over the ADIZ by intercepting civil aircraft over the ECS. Certainly for Taiwan, repeated instances of Chinese military aircraft testing Taiwan’s response time show that ADIZs will remain relevant for the foreseeable future.

LtCol Brent Stricker, U.S. Marine Corps, serves as the Director for Expeditionary Operations and as a military professor of international law at the Stockton Center for International Law at the U.S. Naval War College. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Navy, the Naval War College, or the Department of Defense.

Endnotes

1. Convention on International Civil Aviation, Oct 13, 1919, 11 LNTS 174, reprinted in 17 AJIL Supp. 195 (1923) (no longer in effect).

2. Peter A. Dutton, “Caelum Liberum: Air Defense Identification Zones outside Sovereign Airspace” The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 103, No. 4 (Oct., 2009), pp. 691-709, 692.

3. Chicago Convention Article 3.

4. Id.

5. INT’L Civil Aviation Organization, Convention on International Civil Aviation, Annex 15, International Standards and Recommended Practices, Aeronautical Information Services (16th ed. July 2018). .

6. For a comprehensive listing of AIPs see Hazy Library Emory Riddle Aeronautical University Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Resources: Electronic AIPs by Country (https://erau.libguides.com/uas/electronic-aips-country).

7. James Kraska and Raul Pedrozo International Maritime Security Law 158 (2013); Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, “Air Defense Identification Zones” 97 INT’L L. STUD. 7, 8 (2021).

8. Joëlle Charbonneau, Katie Heelis, and Jinelle Piereder, “Putting Air Defense Identification Zones on the Radar” Centre for International Governance Innovation POLICY BRIEF No. 1 • June 2015 CIGI Graduate Fellows Series at 2

9. J Ashley Roach “Air Defense Identification Zones” Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law www.mpepil.com, https://opil-ouplaw-com.usnwc.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e237; Each country’s ADIZ is defined in its own Aircraft Information Publication (AIP). Joëlle Charbonneau, Katie Heelis, and Jinelle Piereder, “Putting Air Defense Identification Zones on the Radar” Centre for International Governance Innovation POLICY BRIEF No. 1 • June 2015 CIGI Graduate Fellows Series at 4.

10. J Ashley Roach “Air Defense Identification Zones” Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law www.mpepil.com, (https://opil-ouplaw-com.usnwc.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e237).

11. J Ashley Roach “Air Defense Identification Zones” Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law www.mpepil.com, (https://opil-ouplaw-com.usnwc.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e237).

12. Chicago Convention Article 3.

13. Oliver J. Lissitzyn “Legal Implications of the U-2 and RB-47 Incidents” The American Journal of International Law Jan 1962, Vol 56, No.1 pp. 135-142. (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-journal-of-international-law/article/some-legal-implications-of-the-u2-and-rb47-incidents/EF3BFC9B45E842B3A5B298D120DBE241).

14. Lissitzyn at 141 (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-journal-of-international-law/article/some-legal-implications-of-the-u2-and-rb47-incidents/EF3BFC9B45E842B3A5B298D120DBE241).

15. Lissitzyn at 142 (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-journal-of-international-law/article/some-legal-implications-of-the-u2-and-rb47-incidents/EF3BFC9B45E842B3A5B298D120DBE241).

16. Joëlle Charbonneau, Katie Heelis, and Jinelle Piereder, “Putting Air Defense Identification Zones on the Radar” Centre for International Governance Innovation POLICY BRIEF No. 1 • June 2015 CIGI Graduate Fellows Series at 4.

17. “Strauss at 759; “Announcement of the Aircraft Identification Rules for the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone of the P.R.C.,” PRC Ministry of National Defense, November 23, 2013, (http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Press/2013-11/23/ content_4476143.htm).

18. To access the PRC AIP (https://www.aischina.com/EN/indexEn.aspx).

19. Ted Adam Newsome, “The Legality of Safety and Security Zones in Outer Space: A Look to Other Domains and Past Proposals” A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF THE LAWS (LL.M.) Institute of Air and Space Law McGill University, Faculty of Law Montreal, Quebec August 2016 at 47.

20. “Pedrozo at 9-10.

21. Edmund J. Burke and Astrid Stuth Cevallos, In Line or Out of Order? China’s Approach to ADIZ in Theory and Practice 6-7 (2017).

22. Edmund J. Burke and Astrid Stuth Cevallos, In Line or Out of Order? China’s Approach to ADIZ in Theory and Practice 7 (2017).

23. Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, “China’s Legacy Maritime Claims” Lawfare (July 15, 2016) (https://www.lawfareblog.com/chinas-legacy-maritime-claims).

24. Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, “China’s Legacy Maritime Claims” Lawfare (July 15, 2016) (https://www.lawfareblog.com/chinas-legacy-maritime-claims).

25. Edmund J. Burke and Astrid Stuth Cevallos, In Line or Out of Order? China’s Approach to ADIZ in Theory and Practice 1 (2017).

26. To access Taiwan’s AIP (https://eaip.caa.gov.tw/eaip/home.faces).

27. NR 1.12 Taiwan AIP.

28. NR 1.12 Taiwan AIP.

29. To access the South Korea AIP (https://aim.koca.go.kr/aim/main.do).

30. Michael Strauss “China-Japan-South Korea-Taiwan: East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zones” Border Disputes : A Global Encyclopedia: Functional Disputes, 2015, p.759-764, 761.

31. To access Japan’s AIP (https://aisjapan.mlit.go.jp/Login.do).

32. Edmund J. Burke and Astrid Stuth Cevallos, In Line or Out of Order? China’s Approach to ADIZ in Theory and Practice 5 (2017).

Featured Image: U.S. Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps and Air Self-Defense Force aircraft conduct a large-scale joint and bilateral integration training exercise on Tuesday in airspace near Japan. (U.S. Air Force photo)