By Travis Reese and Dylan Phillips-Levine

This is the third and final part of Travis Reese’s CIMSEC Readiness Series. Read Part 1 on properly defining joint readiness, Read Part 2 on how Defense Department planning horizons can better avoid strategic surprise.

The False Dilemma

“Necessity, especially in politics, often occasions false hopes, false reasonings, and a system of measures correspondingly erroneous.” —Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 35, 1788.

“Innovation is [sic] an exercise in risk management, a balancing act between the promises of a new capability and the perils of losing older ones.”—Kendrick Kuo of the Naval War College.

Current readiness and future requirements can be synchronized in DoD, reconciling the tension between contemporary force employment and future force design with the proper framework. The debate on how to balance the paradigms and viewpoints of what are often termed “traditionalists” and “futurists” is something which many national security practitioners appreciate, but little has been done to rectify. Both paradigms of traditionalists and futurists are equally unhelpful to delivering a clear-eyed assessment of the security environment when looked through that singular lens. The misunderstanding between these diametrically opposed paradigms has been historically regarded as an “either-or” statement: the choice is adaptation of existing and legacy means or developing future-minded innovation which may be at the root of this phenomenon. Both camps staunchly dig their heels into the sand and are either reticent to change existing solutions to answered problems or overly enthusiastic about advocating for solutions to potential problems based on the allure of technological promise.

The whole concept of traditionalists and futurists is a little comical given the fact that what is tradition now was once future and what is future assumes that older solutions are merely inadequate because they are old. People in one camp or the other are either reticent to change by disposition or overly enthusiastic about the future sometimes suppressing discussion of risk by overvaluing opportunity.

Despite the entrenched viewpoints between both camps, two complementary models will be detailed in this article that define how to apply the principles of the Horizons of Innovation. These models bridge the gap from traditionalists to futurists and provide a framework to develop the transition from “as is” into the “to be.” These models are designed to help overcome the temptation to remain fixated on the static logic of a traditionalist or futurist point of view. They provide clear criteria to frame objective discussion within the two camps as they assess the implications of the future horizons model on preserving legacy capability or shifting to future means. Horizons of Innovation models create an objective framework to reconcile the current environment with the future before making the risky decision between sustaining the “old” or adopting the “new.”

The First Horizons Application Model shows the level of detail that should populate appropriate timeframes depicted in the Horizons of Innovation. The Second Horizons Application Model accounts for the dynamic response by adversaries to potential innovations and how DoD can gain the most utility from a range of potential capability investments before adversaries respond with effective countermeasures. The Second Model is a framework that minimizes the institutional shock to capability replacement and succession.

Horizons of Innovation Recap

The Three Horizons model introduced by business strategists around the turn of this millennia serves as the inspiration to develop the Horizons of Innovation Model. The operating definitions in this article for innovation and adaptation are derived from remarks by former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joseph Dunford: Innovation is doing new things in new ways with new means and concepts. Adaptation is using current means and applying them to new or emerging challenges.

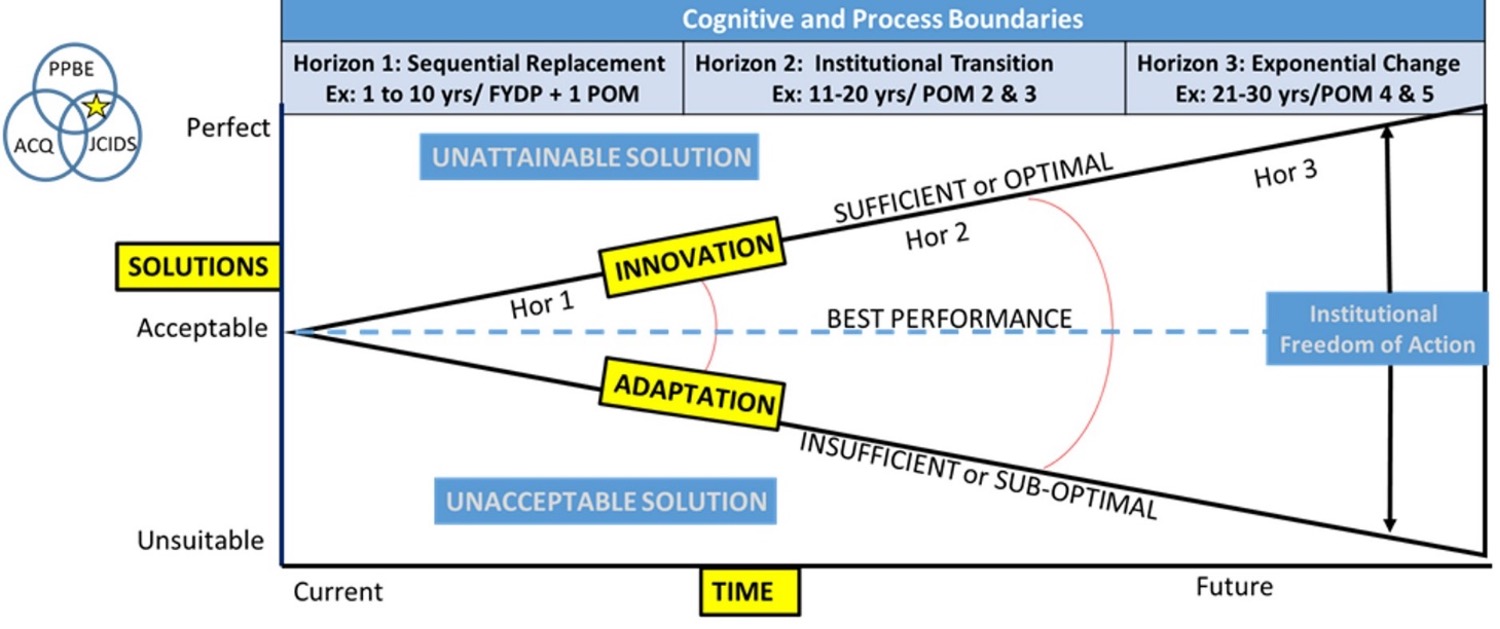

Horizons of Innovation Model is represented in Figure 1. The Horizon Innovation model provides a framework for three horizons. The Y-axis, labeled “solutions” spans the spectrum from unsuitable to perfect. The X-axis, labeled “time” spans from the present into the future. Solutions are constrained by the positively sloped “innovation” line and negatively sloped “adaptation.” All solutions constrained in the angle formed between adaptation and innovation are acceptable where the bisecting dashed line represents the best performance. Solutions that exist below the adaptation line are unacceptable while solutions that exist above the innovation line are unattainable. DoD force planners should look at the limiting lines of innovation and adaptation across the three different horizons of 10, 20, and 30 years to develop the framework to address future challenges.

The historical length of time required to develop technological innovations or adopt new concepts informed the 30 years timeline. This timeline of 30-years from conception to adoption of innovative solutions is a consistent trend (opposed amphibious assault for example) for modern military capability development and precedes many modern bureaucracies. The misguided belief that modern information and manufacturing compresses technology advancement and is only stifled by institutional processes or bureaucratic hinderances to develop or adopt new capabilities is not reflected reality. Recent analysis by the GAO identified the necessity to improve and secure the defense industrial base and confirmed that synchronizing capability development with the needed modifications to industrial capacity to meet future demands is a matter of extreme forethought. Famed futurist Bran Ferren said it best: “We don’t do strategic or long-term thinking anymore. If anything, we may do long-term tactical thinking and call it strategic, but it’s really just a spreadsheet exercise…That’s not a survivable model.”

The issue is not process improvement or increasing efficiencies. The issue is the need to adopt strategic horizons that correspond to the realities of technology development and concept adoption. Defense “professionals” constantly surprise themselves every time a new institutional horizon is established for consideration under a national defense strategy only to discover that industrial base and resources are not prepared for the new problem set. This phenomenon tends to exacerbate the tension between traditionalists – who reflexively hedge by advocating for “tried and true” capabilities – and the frustrated futurists who don’t understand why their certain vision of the future isn’t accepted and quickly translated into physical reality.

First Model: Framework for detailed future projections and reconciling emergent challenges

The hardest thing about future analysis is to reconcile projections with current, or emergent, challenges. In 2014 the discovery of large gaps in defense capacity due to Russian and Chinese development over the Global War on Terror (GWOT) years created a need to energize “innovation” and pursue “disruption”. Those buzzwords proliferated in the new defense jargon around the 3d Offset Strategy and the supporting Long Range Research and Development Plan initiatives The use of the Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO) to cover emergent Combatant Commander-identified gaps along with the creation of DIUx to better integrate with America’s technology base were direct reflections of the mindset forming around how to sponsor and conduct defense innovation. As the reality of future capability needs found itself at odds with the timeline to see true technology development occur, the rift between traditionalists and futurists only grew. As a result, strategists did not develop a process or method to reconcile transition from old to new as a matter of managed risk around a set of common criteria that would satiate the conflict between “as is” traditionalist and “to be” futurists.

However, as the reality of future capability needs settled in along with an appreciation of how long it takes to see true technology development occur, the confrontation between how to manage current and future by traditionalists and futurists was never resolved in defense culture or process. One reason why was that there was no clear engagement on how the continuum from current to future should be managed nor what level of detail should populate long range projections compared to near-term realities. Worse, there is still a lack of direction on how to manage normal capability succession if an unanticipated adversary capability is identified that may pre-empt planned investments or divestments, especially if the problem is severe or urgent enough that it requires redirection of re‐ sources. The First Model below provides clear steps to introduce a process to reconcile legacy and future requirements.

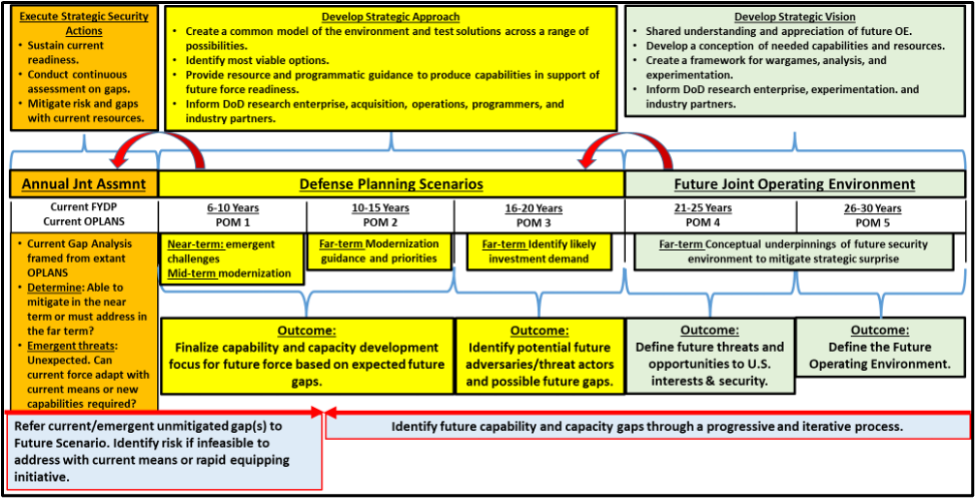

The model above shows the level of detail that should inform discovery, learning, experimentation, and investment for different planning horizons. This model reads from right to left. Planning conducted in the 30-year block on the far right is broken into 5-year increments. Its focus is on the conceptual framework that underpins plausible security situations in 30 years, derived from long-term trends to include: demographics, economics, technology projections, and other factors. The effort of the 30-year period shapes a future defined by the projected operating environment and captures potential threats and opportunities to U.S. security interests. The 30-year projection then gives way to the 20- and 10-year horizons. Finally, this model shows that emergent or unmitigated gaps discovered in the Annual Joint Assessment of the current environment, for which there is no near-term resolution, can be referred to future analysis.

If no solution exists to mitigate a gap with current capabilities, the solution becomes an object of future consideration. The level of risk determines how soon a gap must be filled. As a caveat, this is not a form of “backcasting,” which is often used in future disciplines to define a future state and then identify how in the contemporary environment that desired outcomes should be achieved. This is decidedly not path determinant in that manner, it is simply a guide to the level of detail that should populate strategy and planning activities in each Horizon. Long-term projections are necessary to shape sustained development efforts, but not at the discounting of emergent conditions. Conversely, the emergent pressures of the “now” should not divert all attention from the future as it may set a detrimental course that will impact long-term security.

To develop an effective understanding of the future as it may impact the security environment must be a continuous effort. That future environment is often depicted in the form of defense planning scenarios. However, tension often arises about how much detail a scenario should have. Regardless of the detail requirements, the model effectively shapes 30-year projections through a process of assessment and then, with increasing details, converts assessment into an actionable criterion for defense strategy. Future projections are reconciled to the Joint Strategic Planning System (JSPS) process of force design (five-15 years), force development (two-seven years), and force employment (zero-three years) for the Joint Force synchronized with the Services. The Annual Joint Assessment conducted as part of the JSPS quantifies the capacity of the Joint Force to address current challenges and identifies any newly revealed and emergent threats from adversaries that were not anticipated in Force Design. These emergent concerns are considered and referred to the Joint Staff and Services for resolution. If an arriving capability fills the gap in an acceptable period, then transition can continue. If an emergent challenge is significant enough and a near-term solution can be delivered within two years, then the adjustment to timelines and budgets must be made. If, however, an emergent challenge cannot be mitigated in the near term and is expected to be a continuing challenge with long-term impacts to Joint Force effectiveness, it needs to be allocated to a horizon timeline with corresponding priority where research and experimentation can begin, even if it offsets other newly recognized lower priority efforts.

The First Model also helps to create cognitive space between current programs and future programs to enable honest assessments in each timeframe. It keeps these time periods from being conflated thus, avoiding unnecessary confusion between traditionalists and futurists when it comes to assessing the utility of legacy or future capabilities. It shows how to sustain a constant flow of future projections that mature in detail the closer one gets to the period under question while also accounting for near-term risks. This model establishes the level of detail that can feed a future projection and corresponding defense planning scenario based on its relevant timeframe thus impacting the level of analysis that can contribute to programmatic decisions.

For example, analysis in the 20-year timeframe may only be able to inform decisions to investigate a broad range of solutions or pursue basic or applied research vice selection of specific projects or solutions. Analysis in the 10-year timeframe should be more detailed and aligned with the current operating environment to inform final acquisition decisions and capability transition. Allowing current force commanders to contribute to future analysis in the 10-year horizon can prevent chaining DoD to an exclusive fixation on current concerns at the expense of future readiness while serving to eliminate any anchoring and availability bias in DoD planning and programming.

DoD struggles with how to weigh the consequence of emergent discoveries against other anticipated threats that have been matured and modeled over years. Posture hearings and testimony in front of Congressional committees play this drama out repeatedly as lawmakers question Department staff, Combatant Commanders, and Service leaders over which problem is the greatest and where to focus resources. Often the consequence of immediately allocating resources to an emergent problem is not reconciled against the impact for long-term shaping of force design efforts. The First Model both mends the rift between traditionalists and futurists while clarifying the depth of detail to inform multiple planning horizons. This model provides a solution to end the long-standing chasm between traditionalists and futurists misunderstanding through a mutually beneficial model with clear and common appreciation of the framework from which they view security challenges and remedies.

Second Model: Material and Technology Obsolescence vs Threat Obsolescence

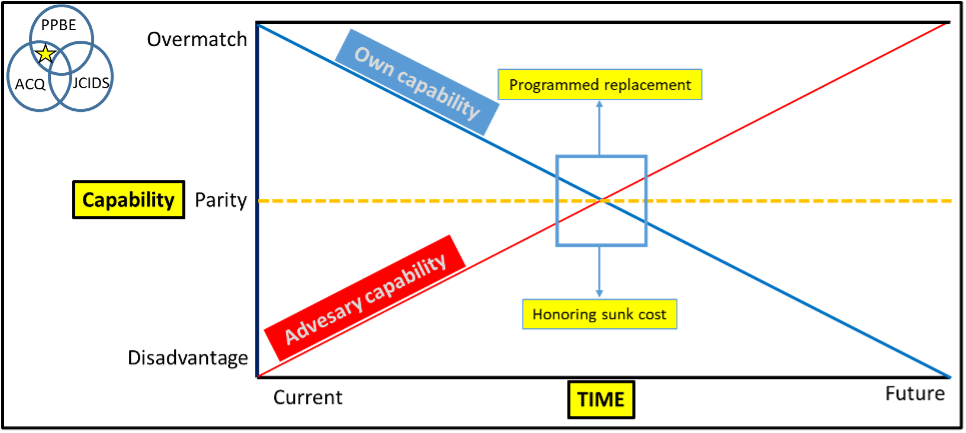

Many proposed future capabilities are increasingly complex technologically both from a hardware and software perspective. Many extant capabilities, having proved their worth in previous generations, become the paradigm of successful means despite indicators that they may not be effective in the future. It is tempting in DoD to avoid re-assessing the efficacy of a capability against an adversary once it becomes a program of record regardless of whether it is an evolutionary or revolutionary capability due to the length of investment of time, money, and institutional alignment around the acquisition effort. Threat information contained in requirements documents introduce a single appreciation of the adversary once signed. Ironically, the need to re-assess increases the longer the capability dwells in development. Potential shifts in adversary capability throughout the capability development and acquisition process is something that demands updating. The Second Model illustrates the importance of a continuous assessment for adversary capabilities during a capability development to assess current legacy systems or their future programmed replacements.

In the Second Model depicted above, the Y-axis, labeled “capability,” spans the spectrum of our relative capability against an adversary. The X-axis spans time from the present to the future. Every capability DoD produces moves along the negatively sloped “Own Capability” line from useful to useless as it materially degrades over time. In the “Own capability” line, current capabilities are useful to provide overmatch, followed by neutral or parity as materiel condition over time, then followed by disadvantage as materiel condition and lack of sustainment render the current capability as useless. To exacerbate the entropic “Own capability” line, adversaries also decrease the time of usefulness of “own capability” since adversaries have their own negentropic positive sloped “Adversary capability” line. For each “Own capability,” adversaries adapt and introduce their own means to decrease time to make our “own capability” transition from useful to useless. The intersection of “own capability” and “adversarial capability” creates a point of competitive parity where sustained “own capability” beyond competitive parity generates an unnecessary risk to force and mission.

DoD generally does not consider of the ways that an adversary could respond after the decision to commence research and development of a new capability. The Services generally presume they will start from a position of overmatch and replace the capability as a technology improvement creates an advantage that makes retiring a system worthwhile compared to the expense of its development. The Second Model demonstrates that the adversary capability shift from disadvantage to overmatch may happen faster than the Services project. This template delivers an objective case for how both futurists and traditionalists can bridge the gap from their respective biases when they consider the adversary capacity to overcome either evolutionary or revolutionary means. Depending on the overmatch-disadvantage and present to future deltas, both traditionalists and futurists can assess feasibility of any capability opportunity and whether long-lead technology or a rapid and cheap adaptation is better in the face of an ever-changing adversary.

Peer and near-peer threats seemed less likely just 10 years ago, which afforded the luxury of capability introduction and replacement to be based on self-assessed warfighting improvements that dominated the approach to acquisition and sustainment. This self-assessment helped facilitate multi-mission exquisite platforms and was based on what the U.S. wanted to do or achieve given the low probability, or even lack of consideration, of a peer competitor. The perceived economy of multi-role platforms was derived from the need to have optionality in functions vice specificity derived from a single, or potent grouping, of comparable adversaries. The U.S. largely enjoyed the luxury of time for making features of the systems the dominant design variable rather than the threats they were devised for. A capability was threat informed but largely for adversaries expected to lack the capacity or means to rapidly respond with an effective countermeasure. The Services honored their invested preferences by sustaining capabilities as long as possible either in their original form or through ad-hoc adaptations that did not require major revisions to stave off obsolescence. Spiral development approaches of single systems informed this method with notable examples include the M2A2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle or most of the Navy’s weapons programs and ship construction. In the years of the GWOT, most adversary capabilities, although potent, did not stress the ability of the acquisition system to provide a capable response, just the willingness of the bureaucracy to accept the demand and energize appropriately.

In recent years the U.S. and its allies have seen the ability of adversaries to offset their capability overmatch. Near-peer adversaries are now capable of operating in environments that defy or limit the use of many primary systems to affect conventional deterrence or that present credible high-end capabilities that may achieve an overmatch to U.S. means and systems. With adversaries devoted not simply to regional concerns but limiting U.S. and allied efforts to check their global influence, the moment a capability is introduced, there should be an expectation that an adversary will develop a countermeasure; both symmetrically and asymmetrically. The cost imposing strategy of responding to a well-developed measure with a cheap countermeasure should cause DoD to change the timeframe the Services should expect utility from capabilities and consider replacements.

Honoring sunk cost and assuming good stewardship of resources based on giving the taxpayer a “return on investment” by merely sustaining or adapting a capability is no longer a viable economy in the face of expected countermeasures for all but a few systems or platforms given the capacity of adversaries to respond technologically and materially. For this reason, force developers and force designers should meet often to develop clear appreciations of what capabilities or concepts will resolve adversary capacity at the point they achieve parity. More importantly, it should give pause to consider many long-lead programs if the time of utility is dramatically less than expected or if the proposed capability gap can be filled by a significantly cheaper and more risk-worthy option before parity is achieved.

Although the U.S. will be unlikely to see very many capabilities that will truly be useful for 30 years that are worth enormous time and capital investments, those that are pursued for 20 years with an expected service life of 20 or 30 years need to have assumptions of their utility validated during the development cycle with a dynamically considered adversary, and not one statically anchored. Only a concerted effort to develop an objective framework offered by the Second Model can help the critical traditionalist versus futurist debate into an actionable accord that delivers platforms and solution.

Conclusion

There should be no false boundary between those who choose to be either traditionalists or futurists. True defense professionals appreciate both perspectives and understand that each is subject to assessment of the claims advocated by either side. One method to address this challenge in DoD culture is to adopt an approach to capability development that treats current and future as a part of a continuum. The Horizons of Innovation illustrate that principle supported by the two subsequent detailed models. From the Horizons, institutional strategists, capability developers, and acquisition professionals can better identify when a capability will face obsolescence, not just due to material degradation but also to adversary response. Merely improving the bureaucracy is insufficient alone to accelerate the choice between innovation and adaptation.

The key process for DoD to gain maximum advantage is to adopt a longer-range strategic scan and continually update and compare multiple horizons against each other. More importantly, the ability to make a compelling case between sustaining current technology or adopting future technology depends entirely on developing measured and accurate models of future concerns that are more right than wrong which can only occur through sustained institutional learning and study.

Travis Reese retired from the Marine Corps as Lieutenant Colonel after nearly 21 years of service. While on active duty he served in a variety of billets including tours in capabilities development, future scenario design, and institutional strategy. Since his retirement in 2016 he was one of the co-developers of the Joint Force Operating Scenario process. Mr. Reese is now the Director of Wargaming and Net Assessment for Troika Solutions in Reston, VA.

Dylan Phillips-Levine is a naval aviator assigned to a tactical air control squadron. His Twitter handle is @JooseBoludo.

Featured Image: Busan, Republic of Korea (Feb. 23, 2023) Tugboats assist the Los Angeles-class fast-attack submarine USS Springfield (SSN 761) as it pulls into port in Busan. (U.S. Navy Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Adam Craft)