There are two extremes in public discourse over China and the ambitious naval modernization campaign that the People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLAN) has undertaken over the last two decades. On one hand, China is often presented as an existential threat whose massive naval build-up in both weapon quantity and quality, coupled with a newly aggressive foreign policy, makes it poised to directly challenge U.S. dominance of the high seas and hegemony in the Western Pacific. Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, China is portrayed as a rational major player within an interlinked global economic system, for which conflict with the U.S. or other regional powers such as Japan, South Korea, and even Taiwan, would be unthinkable and ruinous. Regardless of which depiction is more representative of reality, in an era of impending defense cutbacks, budget battles of the near future will repeatedly reference Chinese naval modernization as the driving justification to buy, develop, or retain all sorts of weapons and capabilities.

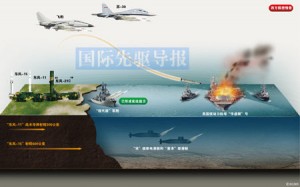

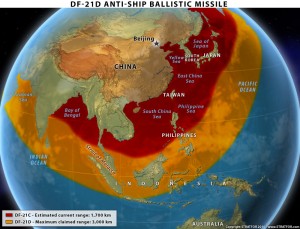

What has really been missing from much of the public debate over the Chinese navy is a holistic analytic framework to aid understanding of the potential impact of China’s burgeoning capabilities in a Sino-American conflict. This would be done through a better understanding of Chinese intentions in terms of its doctrine and both foreign and domestic policies. Those policies are not necessarily aligned. Toshi Yoshihara and James Holmes’ Red Star over the Pacific discusses these issues, but their careful review of the evolution of Chinese naval strategy is not mirrored in discussions of China’s in the blogosphere. A focus on Chinese naval weapons system developments (the latest unveiling of a new Chinese ship, plane, missile, etc) can lead to both hysteria and conflicting calls for action. For instance, while the DF-21 Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile could potentially be a game-changing weapon impacting how war at sea will be fought in the future, it has yet to be fielded. However, some critics have already used its development to argue for the elimination of carriers and large surface combatants (because they are now potentially vulnerable), while others see its development as evidence of malign Chinese intent that justifies an American naval revitalization – presumably achieved by building many more large surface combatants.

A holistic analytic framework would assess 1) The elements of Chinese efforts comprising what is now commonly referred to as “Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities, 2) the “quantity and readiness” of Chinese maritime power, and 3) Chinese strategy and policy. These factors form a three-legged stool of sorts, all of which must be in place for the argument to rest that China has the ability and intent to do harm to U.S. forces at sea, and therefore a U.S. naval expansion designed to counter China is merited (rather than one to ensure the U.S. Navy has the combat capability to meet US foreign policy objectives around the world).

A2AD:

• Chinese developments in the cyber domain are often cited as significant threats to U.S. naval operations. These threats range from jamming U.S. satellite and wireless communications networks, disrupting communications and preventing the means for effective Command and Control (C2), to cyber attacks on U.S. information technology, crippling dependent American C2 systems. Is China capable of executing cyber attacks that can cripple U.S. combat operations afloat?

• China has made a significant effort to build and buy a variety of the most modern and capable naval and air platforms currently available. These include new submarines, ships, and airplanes. Are these qualitatively superior to their American counterparts?

• China is also acquiring a variety of cutting edge high-end anti-ship cruise missiles and the already noted DF-21. Will these make it impossible for an afloat task force in its current incarnation to operate at sea in the Western Pacific as the U.S. Navy has grown accustomed to? Will these prove too much for the current generation of American countermeasures?

Quantity:

• While all the new weapons mentioned above present an abstract threat to U.S. naval forces in the sense that they seem extremely capable and represent the cutting edge of technology, are they now or will they ever exist in large enough numbers to present an actual threat to U.S. Navy operations?

• In the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, the Chinese wouldn’t necessarily need numerical superiority over the U.S. force assembled in response, but how much capability would they need to bring to the fight in order to accomplish the mission? Regardless of how much “quality” navy they bring, how much “quantity” does China need before the balance tips in their favor?

• While all this new technology might be highly capable, Can Chinese forces effectively use it to maximum effect? Can they maintain this equipment? Do they have the logistics and infrastructure to support fielding it in combat?

• Are Chinese efforts towards cyber dominance integrated with their improvements in more conventional naval weapons and capabilities?

Strategy and Policy:

• Why are the Chinese pursuing a naval build-up? Is it driven by a bureaucratic impulse of the PLAN, a nationalist desire to be the regional hegemon, or the result of what China perceives as external security threats by the U.S. or other regional powers?

• What would drive China towards attempting a military takeover of Taiwan? Have they figured out how they would actually fight with the navy they have built?

• Does Chinese maritime strategy reflect the same principles as those of the U.S. Navy’s, in which maritime forces are important because they are the critical enablers for power projection across the globe, or do they simply represent an expansion of land power?

There are many conflicting answers to these questions, pointing towards many different potential conclusions. There is no simple answer as to whether Chinese naval modernization represents a grave threat to U.S. interests or what that means to the U.S. Navy’s acquisition efforts. Regardless, the need for deep and sustained analysis of China is merited and should be a high priority. In the mean time, one should be wary of simplistic analysis using the latest splashy announcement of a new Chinese ship/plane/missile to justify a particular course of action, particularly when linked to future defense acquisition strategies (Build more ships! Build less ships! Shift focus to/from carriers/amphibs/fighter jets/subs/SOF/unmanned systems/cyber!) Chinese capabilities and intentions need to be understood in their totality before driving shifts in U.S. defense policy.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a Naval Intelligence Officer and currently serves on the OPNAVstaff. He has previously served as at Naval Special Warfare Group FOUR, the Office of Naval Intelligence and onboard USS ESSEX (LHD 2). The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.