The age of Fourth Generation Gaming is upon us. With the launch of the PlayStation 4 this week and the Xbox One next week, the younger side of me emerges from its shell with interest. As we step into this new age of gaming, one has to wonder if these new sophisticated gaming devices have the potential to contribute to professional military training and education in an age of fiscal austerity. This article argues that specific video games provide users the opportunity to practice ground and naval warfare tactics in addition to leadership skills.

Going Beyond the Call of Duty

When one simultaneously thinks of the military and video games, notable first-person-shooters (FPS) such as Call of Duty and Battlefield come to mind. As fun as these games may be, they unfortunately serve the military little purpose besides acting as a recruiting tool. Yet, one title that focuses on land warfare (and dabbles in the maritime area) is the Arma series. Based off of the Virtual Battlespace engine, Arma II and the recently released Arma III bring unparalleled realism to the gaming realm. Accurate bullet ballistics, radio communications, wounding, and scale of the terrain are several features among many that create a multiplayer (players against players, not AI) platoon or company level large scale engagement. In addition to these realistic features, the Arma series features a comprehensive and versatile, but yet easy to use mission editor allowing users to set-up almost any tactical engagement in mind (I personally created a mission entailing a situation in which USMC forces had to assault a captured oil rig with helicopters and small boats; this mission exposed the tactical difficulties of VBSS as my team did not anticipate searching every inch of the complex platform for OPFOR.)

Although the educational benefits of playing a FPS video game may appear to be nonexistent, the Arma series illustrates that tactical lessons at squad, platoon, and company levels can be learned. Players can simulate a variety of engagements ranging from 300+ meters in mountainous terrain modeled after Afghanistan to larger conventional fights with armor and mechanized infantry (a typical Arma engagement video). At the squad level, players practice moving as a unit in different environments (rural and urban) against different enemies (unconventional guerrillas, rag-tag Third World armies, and sophisticated Russian and Chinese militaries). A different set of challenges confronts players commanding a platoon or company as they have to not only ensure that their units remain organized and move coherently, but also penetrate the fog of war to determine how to best apply their forces strategically, practicing combined arms operations (a skillset with potent consequences if forgotten).

Other games such as Combat Mission Shock Force and Flashpoints Campaign: Red Storm also provide players with the opportunity to experience with small-unit tactics, but the dynamic pace of the Arma series challenges players in ways these other games lack. Although the Arma series fails to embrace the maritime domain of war (with a few exceptions such as my team’s bungled oil rig assault), fortunately other games are available to provide players with this opportunity.

Bringing a CIC to Your Living Room

Less than a handful of video games embrace the concept of naval warfare, but the few that do surpass their users’ expectations. Many mimic the style of the notable Harpoon series by featuring an interface similar to a CIC rather than amazing visuals. One recent title, Command: Modern Air/Naval Operations, simulates naval tactics and operations by allowing players to command a variety of units ranging from a single destroyer tasked with ASW to all of the assets under the command of the 5th Fleet (even nuclear weapons are included, with dangerous consequences). Players command their unit(s) through a CIC-type interface. Accompanying the game is an enormous encyclopedia containing an endless amount of statistics for every ship, aircraft, and weapon automatically factored into gameplay. Unfortunately, all of these variables make playing the game itself a hard experience with a difficult learning curve (grasping the controls while being pummeled by Russian Backfire bombers does not help). Yet, this illustrates the complexity of how a carrier battle group functions. Fortunately, some of these features can be delegated to the Al (such as engaging with the most optimal weapon). For further information about Command, USNI published an excellent review.

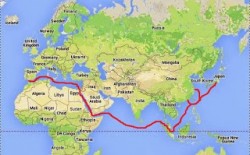

Command’s ultimate benefit is its vast scale. The ability to employ nearly any naval or air unit in any corner of the globe allows players to experiment with various situations and conflicts including counter piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, transiting the Strait of Hormuz while being harassed by dozens of Iranian missile boats, counternarcotic operations off the coast of South America, and repelling Chinese A2/AD forces in the Pacific. Some units and methods work almost perfectly in some situations but fail in others. Players experience both the tactical and operational challenges in these various scenarios. Although the game lacks stunning visuals or sounds, it gives users a vast sandbox to practice a wide array of naval tactics.

Leadership: Practice, Practice, and Practice Some More

The previous two games discussed both allow users to practice maritime and ground tactics. These skills are incredibly important but by themselves do not make a great officer. I argue that leadership is another key trait. Although leadership (in my opinion—many others would disagree) is a natural trait that not everybody possesses, those that have this trait only improve their leadership abilities through experience; typically, the more someone leads, the better leader they become. There are almost infinite amounts of ways to practice leadership, but one that stands out is a video game titled EVE: Online.

Thinking of EVE as a tool to practice leadership may appear to be out of this world (literally because of the science-fiction feel), but it is not. EVE is a science-fiction space game in which players fly their ships around different star systems for combat, industrial, commercial, and exploration purposes. In EVE, all players (approximately 500,000) are on the same server, making the game persistent, and player-driven (for example, corporations—or alliances—fight over sovereignty over key systems linking resource-rich areas with market hubs). Few ‘rules’ exist in EVE (although corporations try to enforce certain laws) allowing players to conduct practically any activities they desire. The economy is completely player based, making the most expensive ships in the game tradable for over $3000 USD (a lot of cash at stake for a ‘recreational’ video game).

Now, how does this game with spaceships simulate leadership experience? Essentially, Fleet Commanders in EVE are always applying Col. Boyd’s famous “OODA” loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act); the most successful Fleet Commanders are masters of this process. Combat in EVE is extremely complex with different types of ships (agile frigates, electronic warfare, logistics, stealth bombers, carriers, dreadnoughts, and many more) that each fulfills important roles; 3 battlecruisers with 3 logistics ships can easily take on 10 battlecruisers. A Fleet Commander needs to account for all of these variables when in the midst of a 3000+ ship battle. The Fleet Commander also ponders how he will get his 1000 ship fleet organized and to the staging area in a time efficient manner (Woody Allen once said that 80% of life is just showing up. In EVE, many “battles” are decided before they commence as players will only risk losing their thousand dollar fleets in fights they can win.), counterintelligence issues from spies embedded in his fleet, and his ultimate objectives. When targeting other ships (in combat, commanders tend to focus all of their firepower on only a couple of targets at a time), the Fleet Commander needs to analyze the changes in both the enemy and his fleet compositions while sounding confident over communications.

As earlier mentioned, EVE essentially provides players with a dynamic environment to constantly practice the OODA thought process. Despite its unrealistic setting, EVE demonstrates how a player-driven video game with a complex—but yet simple—combat system can serve as a tool to for users to practice the strategic thinking. In fact, some may argue that its completely fictional setting removes a commander’s obsession with certain assets and forces him to rely on the core aspects of leadership and critical thinking.

Integrating Video Games into Military Training?

This article is not arguing that the US military institutions should replace their training with video games like EVE (although this may be more reasonable in 2154). Yet, with the conclusion of major military operations and inevitable decline in military training exercises in an age of fiscal austerity, officers will have fewer opportunities to learn from practicing their leadership abilities and experimenting with different tactics. Thus, after illustrating several examples of video games providing educational lessons, this article argues that integrating video games with training may serve as part of a solution to this upcoming gap.

Bret is a student at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, but currently abroad in Amman, Jordan studying International Politics and Arabic. The views expressed are solely those of the author.