Daniel Drezner is an International Politics professor at Tufts University with an informative and entertaining blog at Foreign Policy. He recently published an article in the journal International Security asking whether “military primacy yields direct economic benefits.”

This is an important issue for seapower advocates, with organizations like the U.S. Navy traditionally claiming that American dominance at sea is part of the bedrock foundation of a smoothly running international economic system. The 2007 Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower argues that the “maritime domain…carries the lifeblood of a global system that links every country on earth,” and that “United States seapower will be globally postured to secure our homeland and citizens from direct attack and to advance our interests around the world that relies on free transit through increasingly urbanized littoral regions.”

The 2010 Naval Operations Concept similarly envisions U.S. naval forces that “effectively conduct the full range of maritime security operations and are instrumental in building the capacity, proficiency and interoperability of partners and allies that share our aspiration to achieve security throughout the maritime commons.”

Drezner examines three potential ways in which a state’s military primacy could provide tangible benefits:

1. Geoeconomic Favoritism: “Military preeminence” may spur private sector investment both domestically and from abroad, as “all else being equal, a country is far more likely to attract foreign capital if it is secure from foreign invasion.”

2. Geopolitical Favoritism: Weaker states may “provide voluntary economic concessions to the dominant security actor.”

3. The Public Goods Benefit of Military Primacy: Military “primacy facilitates the creation of global public goods” with “a wide range of international relations theorists” claiming “that a liberal hegemon is a necessary and sufficient condition for the creation of an open global economic order.”

The particular potential benefits of U.S. seapower in its current, globally-deployed state would most likely be realized in terms of the “Public Goods Benefit.” The particular hypothesis which Drezner is trying to test here is whether “by acting as a guarantor of the peace in hotspots such as the Middle East and Pacific Rim, the United States keeps the international system humming along-which in turn yields significant benefits to the United States itself.”

In terms of concrete examples of how the U.S. military has secured the global economy by protecting the sea-lanes, Drezner cites naval operations in the Middle East, an area of both political instability and significant economic importance due to the need to securely ship oil out of the region as well as the recent multi-national campaign against Somali pirates. However, he then proceeds to question whether naval or military power can be credited with minimizing energy market disruptions or defeating piracy, pointing out that “world oil markets” can be relatively resilient and are capable of adjusting to severe price changes, and that “improved private security on board” merchant shipping may have been a more important factor in the decreased threat from Somali pirates. With his focus being military power in general, however, he does not provide a detailed discussion of seapower’s role in the global economy other than his brief discussion of oil and piracy.

Drezner claims that if “unipolarity” and military primacy worked as predicted, China should have been “pacified” by the various manifestations of U.S. policy towards the Far East as part of the the 2011 “pivot,” but instead has acted increasingly aggressive towards its neighbors. Unaddressed in this article, yet probably at the top of the list of factors impacting and/or justifying continued U.S. naval hegemony in the Pacific, is the tangible impact of growing Chinese strength afloat. It is often assumed by China-phobes that a China with a strong navy acting assertively in regards to its claims over the surrounding oceans would be bad for the international system (presumably through somehow limiting freedom of navigation in the region), hence justifying continued American military presence in the Pacific. However, there is no empirical evidence to prove that case yet (because it has not happened), and advocates of both sides are forced to rely on hypotheticals. Drezner has asked the right macro-level questions, but it is unclear if there is specific enough data to generate a definitive answer regarding the tangible benefits of specifically American (or Chinese) naval primacy in East Asia.

Drezner concludes that military primacy is an important resource for a Great Power, but that “military preeminence” alone does not produce “significant economic gains.” Although primacy can be an “an important adjunct to the creation of an open global economy and the reduction of militarized disputes and security rivalries,” a hegemon whose economic strength is declining may not be capable of reaping the benefits of the economic system it has established and protected.

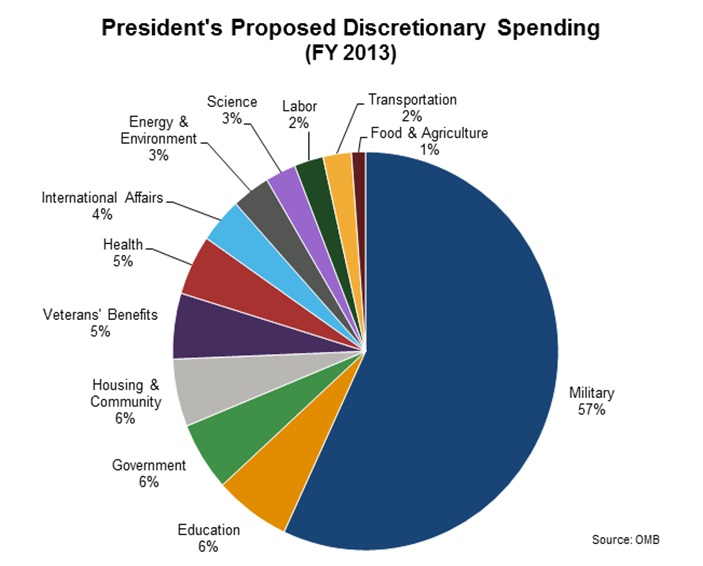

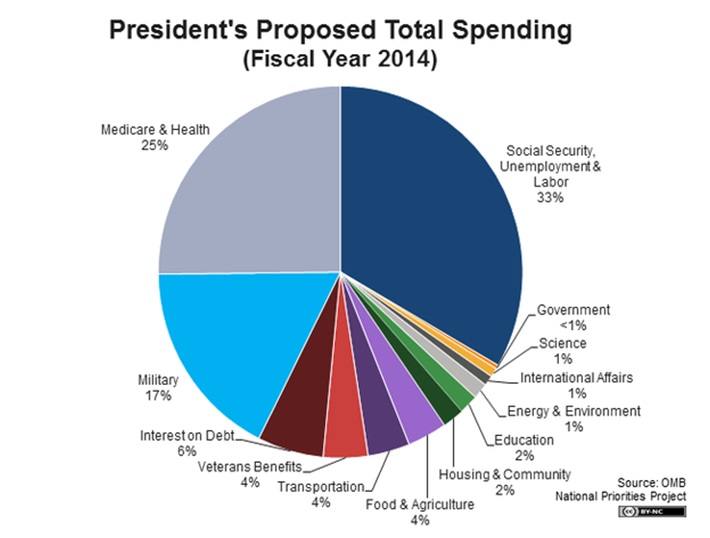

While members of the sea services or naval enthusiasts generally embrace the notion that seapower is an important element of protecting the international system and prosperity both at home and abroad as undisputed truth and gospel, the jury is still out on whether military power is always worthwhile in economic terms, and Drezner questions those often reflexive assumptions here. In an era of budget uncertainty, the Navy needs to have good tangible answers to justify its continued existence when these types of questions are asked in the future.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a Naval Intelligence officer currently serving on the OPNAV staff. He has previously served at Naval Special Warfare Group FOUR, the Office of Naval Intelligence, and onboard USS Essex (LHD 2). The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

However, geostrategic realities on the Korean peninsula and in the Persian Gulf might be more complex than they appear. On the peninsula, the two Korean states

However, geostrategic realities on the Korean peninsula and in the Persian Gulf might be more complex than they appear. On the peninsula, the two Korean states