A continuation of The Hunt for Strategic September, analysis on the relevance of strategic guidance to today’s maritime strategy(ies). As part of the week we have encouraged our friendly international contributors to provide some perspective on their national and alliance strategic guidance issues.

In an earlier article for CIMSEC, I argued that in order for the U.S.-South Korean alliance to effectively counter threats emanating from North Korea (DPRK), South Korea (ROK) must gradually move away from its Army-centric culture to accommodate jointness among the four services. In particular, as Liam Stoker has noted, naval power may offer the “best possible means of ensuring the region’s safety without triggering any further escalation.”

The appointment last week of former ROK Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Choi Yoon-hee as the new Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff seems to augur a shift in focus in the ROK’s strategic orientation. Given that the ROK’s clashes with the DPRK have occurred near the contested Northern Limit Line throughout the late 1990s and 2000s, President Park Geun-hye’s appointment of Admiral Choi as Chairman of ROK JCS seems to be appropriate. Indeed, during his confirmation hearings two weeks prior, Admiral Choi repeatedly vowed retaliatory measures in the event of another DPRK provocation.

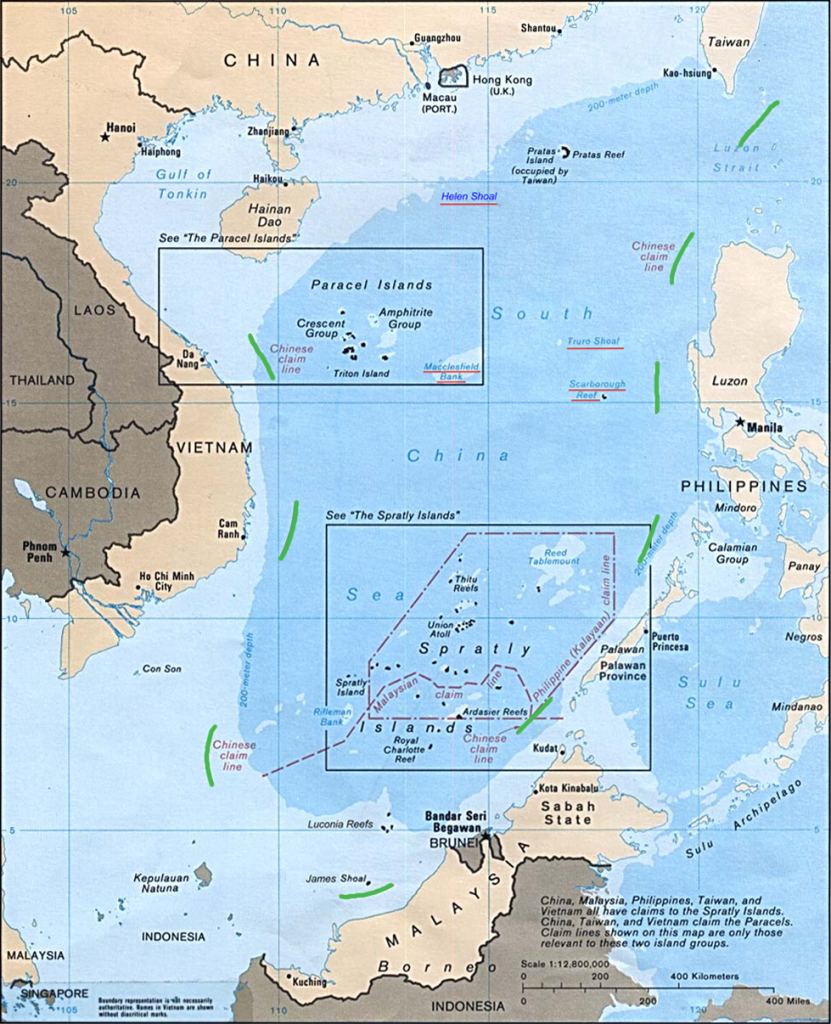

Furthermore, by tapping Admiral Choi to head the ROK JCS, President Park also appeared to signal that she is mindful of the feverish East Asian naval race. The ongoing naval race among three East Asian naval powers (China, Japan, and South Korea) is rooted in historical grievances over Japan’s wartime atrocities and fierce competition for limited energy resources. These two factors may explain the ROK’s increased spending to bolster its naval might.

Indeed, the ROK Navy has become a great regional naval power in the span of a decade. The ROKN fields an amphibious assault ship, the Dokdo, with a 653 feet-long (199 meters) flight deck. The ship, named after disputed islets claimed by both the ROK and Japan, is supposedly capable of deploying a Marine infantry battalion for any contingencies as they arise. Given that aircraft carriers may offer operational and strategic flexibility for the ROK Armed Forces, it is perhaps unsurprising that “funding was restored in 2012” for a second Dokdo-type aircraft carrier and more in 2012 and that Admiral Choi has also expressed interest in aircraft carrier programs. Moreover, the ROKN hassteadily increased its submarine fleet in response to the growing asymmetric threats emanating from North Korea and Japan’s alleged expansionist tendencies. As the Korea Times reported last Wednesday, the ROKN has also requested three Aegis destroyers to be completed between 2020 and 2025 to deal with the DPRK nuclear threats and the naval race with its East Asian neighbors.

Thus, at a glance, it would appear that the ROK has built an impressive navy supposedly capable of offering the Republic with a wide range of options to ensure strategic and operational flexibility. However, this has led some analysts to question the utility and raisons d’être for such maintaining such an expensive force.

Kyle Mizokami, for example, argues South Korea’s navy is impressive, yet pointless. He may be correct to note that the ROK “has prematurely shifted resources from defending against a hostile North Korea to defeating exaggerated sea-based threats from abroad.” After all, at a time when Kim Jŏng-ŭn has repeatedly threatened both the ROK and Japan, it may be far-fetched to assume that Japan may “wrest Dokdo/Takeshima away by force.” It would also make no sense to purchase “inferior version of the Aegis combat system software that is useless against ballistic missiles” which does not necessarily boost its naval might.

However, what Mizokami may not understand is that the seemingly impressive posturing of the ROKN does not necessarily mean the expansion of the Navy at the expense of diminishing Army’s capabilities. As my January piece for the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs and Michael Raska’s East Asia Forum article argue, the greatest barriers to service excellence for the ROKN may be South Korea’s uneven defense spending, and operational and institutional handicaps within the conservative ROK officer corps. One telling indication which bears this out may be the fact that the expansion of the ROKN and Admiral Choi’s chairmanship of the ROK JCS did not lead to the reduction of either the budget allocated for the ROK Army or of the existing 39 ROK Army divisions in place.

Moreover, if, as Mizokami argues, the ROK seems bent on pursuing strategic parity with Japan—and to a lesser extent, China—I should point out that it does not even possess the wherewithal to successfully meet this goal. As I notedin late August, in order for the ROK to achieve regional strategic parity with its powerful neighbors, South Korea must spend at least 90% of what its rivals spend on their national defense. That is, the ROK’s $31.8 billion defense budget is still substantially smaller than Japan’s $46.4 billion. If anything, one could argue that the ROK’s supposedly “questionable” strategic priorities have as much to do with political posturing and show aimed at domestic audience as much as they are reactions to perceived threats posed by its powerful neighbors.

Finally, neither the ROK military planners nor Mizokami seem to take into account the importance of adroit diplomatic maneuvers to offset tension in East Asia. In light of the fact that the United States appears reluctant to reverse its decision to hand over the wartime Operational Control (OPCON) in 2015, the ROK may have no other recourse but to deftly balance its sticks with diplomatic carrots to avert a catastrophic war on the Korean peninsula.

In short, it remains yet to be seen whether the ROK will successfully expand the scope of its strategic focus from its current preoccupation with the Army to include its naval and air capabilities. One cannot assume that this transformation can be made overnight because of an appointment of a Navy admiral to the top military post, or for that matter, because it has sought to gradually bolster its naval capabilities. Nor can one assume that they are misdirected since a service branch must possess versatility to adapt to any contingencies as they arise. Instead, a balanced operational and strategic priority which encompasses the ground, air and maritime domain in tandem with deft diplomacy may be what the ROK truly needs to ensure lasting peace on the Korean peninsula and in East Asia.

Photo credit: U.S. Forces Korea, SinoDefence, ITV

Jeong Lee is a freelance writer and is also a Contributing Analyst for Wikistrat’s Asia-Pacific Desk. Lee’s writings on US defense and foreign policy issues and inter-Korean affairs have appeared on various online publications including East Asia Forum, the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, the World Outline and CIMSEC’s NextWar blog. This article appeared in its original form at RealClearDefense on October 24th, 2013.