If you were aware of the grounding of the British fleet, and the deaths of over 2000 sailors, off the Isles of Scilly, west of Cornwall, in October 1707, then you are either the rare supercentenarian or you are a maritime history geek such as myself. All of this begs the question, why is this date in maritime history so important?

If you were aware of the grounding of the British fleet, and the deaths of over 2000 sailors, off the Isles of Scilly, west of Cornwall, in October 1707, then you are either the rare supercentenarian or you are a maritime history geek such as myself. All of this begs the question, why is this date in maritime history so important?

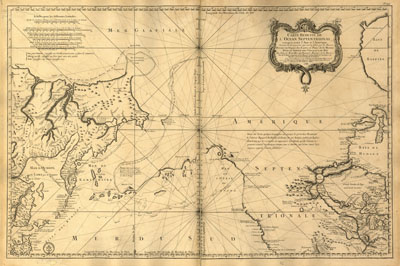

Well since you’re wondering, it took those deaths to get the attention of the Admiralty in solving one of the biggest conundrums in ocean navigation, accurately measuring longitude. Seven years later in 1714 Parliament passed the Longitude Act, [they] convened a Board of Longitude to examine the problem and set up a £20,000 ( $2.5 Million 2015) prize for the person who could invent a means of finding longitude to an accuracy of 30 miles after a six week voyage to the West Indies. It also made minor awards for discoveries and improvements to the general problem. (Citation from The Royal Naval Museum)

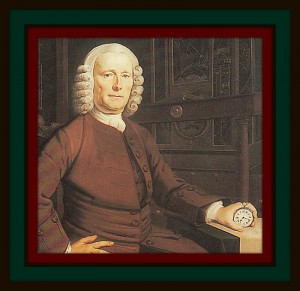

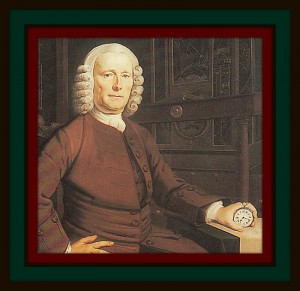

John Harrison undertook this challenge with no formal education or training. By Jove he was just a self taught clock maker! John’s belief was that time would prove the correct measurement of Longitude. He was going head to head with the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, the most prominent proponent of an astronomy-based method. Maskelyne wholeheartedly believed that longitude could be calculated using lunar charts and tables, and that using a mechanical piece was irrelevant.

The prize offered by the Board of Longitude was a tempting one for Harrison and he set out to make a sea-going timekeeper that could keep accurate time to claim the prize. It became his life-long work. The idea was to be able to compare local time to that of the pre-determined Greenwich time (which the timekeeper or chronometer would be set to), and thus find the longitudinal position of the ship.

After years of development and five versions of his time piece, H-1 to H-5, it was a copy of H-4 that accompanied Captain Cook’s  second voyage (1772-1774). The Captain was so impressed with the chronometer that he was able to accurately chart the South Sea Islands. He eventually took the chronometer on his third and final voyage.

second voyage (1772-1774). The Captain was so impressed with the chronometer that he was able to accurately chart the South Sea Islands. He eventually took the chronometer on his third and final voyage.

John, however did not win the entire prize. During the periods of 1765 and 1773 he was awarded a little more than half. In 1774 the Parliament set new standards for winning the prize; all entries must be submitted in duplicate, undergo testing for one year at Greenwich, be further tested on approved voyages by the board.

John Harrison died on his 83rd birthday on March 24, 1776 at Red Lion Square, London. He was buried in a vault in Hampstead church. A tomb was later erected by his son, William. In 1879, the London Company of Clockmakers reconstructed it as a mark of respect for his achievements- even though Harrison had not been one of its members.

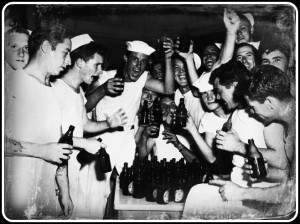

So please, on this day March 24th lift a glass to the man who made a navigators heroes since 1772.

Cheers John!