By Matthew Merighi

Join the latest episode of Sea Control for a conversation with Professor Derek Reveron from the U.S. Naval War College to talk about how the United States military conducts its security cooperation mission and his book on the subject, Exporting Security.

Download Sea Control 137 – Security Cooperation with Derek Reveron

The transcript of the conversation between Professor Derek Reveron (DR) and Senior Producer Matthew Merighi (MM) begins below. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity. Special thanks to Associate Producer Ryan Uljua for helping produce this episode.

DR: Great to be here. And just as the standard disclaimer I am speaking my own personal views and I don’t represent the Navy, the War College, or the Department of Defense.

MM: So, as is Sea Control tradition, please introduce yourself. Tell us a little bit about your background and what were the major things you did which got you to where you are today.

DR: I have a PhD in Public Policy Analysis from the University of Illinois in Chicago and the book represents a fusion of the two parts of my professional life. On the one hand, I’ve been a Navy Reservist for almost 27 years and in that role my career has been marked by the conflicts in the Balkans, Bosnia and Kosovo, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

And then there is the other side of my life which is my academic career that examines U.S. foreign policy and defense strategy. Where the two came together came when I was serving at the NATO headquarters in Kosovo in 1998/99 and I witnessed how the Supreme Allied Commander, Wesley Clark at the time, was both a military leader and, in the academic sense, a policy entrepreneur. He was a senior diplomat working closely with foreign heads of state and the U.S. Secretary of State as well. When I came back from that, I examined others in a similar vein: General Zinni in the late 1990s at CENTCOM and then I got to work with Admiral [William] Crowe a little bit when he was teaching at the Naval Academy and talked to him a little bit about his time at PACOM. What I learned is Combatant Commanders are as much policy entrepreneurs as they are warfighters. They have to be national security leaders, not just military leaders.

MM: You said that’s what prompted you to write your book Exporting Security. Tell us a bit about it. Why specifically write this book? Also, there is a second edition which came out just last year. What prompted you to write not only the first version but the second version as well?

DR: The first edition I wrote during the height of the [Second] Iraq War. It was very clear what the military was doing in a combat zone but when we started looking at the U.S. exit path and strategy success was based on building the Iraqi forces to take over for U.S. forces. I looked more broadly outside of combat zones to see what else the U.S. military was doing and, partly being as a professor, I was able to work with other security cooperation offices primarily in Latin America and East Africa to see what they were doing and the ways they were helping their countries address what I call security deficits.

The second edition was nice to revisit because I found with the first edition that I tilted too much towards weak states and failed states while ignoring developed states. The second edition takes a couple of things into account. One, I got to serve for a year in Afghanistan working at the main NATO training command for the Afghan security forces where we did industrial-scale security cooperation. And then second, looking at the things the U.S. was doing to help developed countries, such as Japan deal with its security concerns on China, Saudi Arabia as it relates to Iran, and then European countries as it relates to Russia. So the second edition takes into account how the U.S. helps developed countries take care of their security deficits.

MM: What are the ways the U.S. addresses security deficits? What are the different levers to pull, methods, and TTPs you end up using for that kind of work?

DR: The simple approach is through Foreign Military Sales. Some of the most important exports from the United States are weapons and training. If you take a particular example of a C-130 transport plane, I think more are flying on other countries’ flags than flying the U.S. flag. As a professor I am deeply involved in the education of foreign military leaders. At the Naval War College we have about 70 countries that send officers and these are top performers.

At any one time, 15 percent of the world’s navies are led by Naval War College graduates. There is a leader development dimension in addition to that. Finally, through exercises is where it all comes together because coalition warfare is the norm. When I was in Afghanistan we had 50 countries that we were working with. Interoperability is key and you get it by operating common platforms through defense exports, from common training and doctrine through education and training, and then you practice that through exercises.

MM: You’ve talked a little bit about some of the reasons embedded in this; not just how we do it but also why. I want you to expand on that a bit more. You mentioned both operational but also strategic reasons why this mission is important. Walk us through what the U.S. gets out of this security cooperation arrangement.

DR: So there’s two sides of it. There’s what we get out of it but also American generosity and political culture explain a lot. There was an officer from Chad who captured the political culture side: “if your neighbor’s house is burning, you should put it out so it doesn’t jump to your own house.” But there is an effort by the U.S. to help other countries be better because if they help them be stronger to deal with their own security challenges than the U.S. will not have to intervene.

Additionally, in combat zones, for the U.S. to redeploy, it needs to hand off the security situation to some other military. In the Balkans we look to NATO to do those missions and we still have KFOR running in Kosovo. In Afghanistan and Iraq it was all about handing it off to the Afghans and the Iraqis. But I think the overall goal is to stabilize the region. So in South Korea, where North Korea is in the news daily now, this is probably one of the best security cooperation success stories because the Koreans were able to use U.S. training and equipment to create a very capable military. So now you have a 700,000-person South Korean force supported by a 30,000 U.S. force.

MM: You also mentioned some of the economic aspects of these relationships and what they can do for the defense industry and industrial base which underpins some of our security advantages. Walk us through some of the political economy aspects of security cooperation too.

DR: From a U.S. domestic perspective, defense weapons are a huge export for the United States. That has multiple aspects: employs Americans, keep lines open, and lowers unit cost. Could you imagine how much an F-35 would be if we didn’t also have international partners buying into that system and bringing that cost down? I haven’t been able to confirm but, informally, someone told me that international buyers of the P-8 caused the purchase price for the U.S. to drop by 10 percent. And then on the other end of why security even matters is economic opportunity. Admiral Stavridis when he was the Commander of SOUTCOM said “money is a coward.” Countries that lack security aren’t going to get investment or trading partners.

MM: So those are the benefits. What are some of the drawbacks of or pushback against the security cooperation mission? This reflects some of the things I saw in the Air Force, and I should put in the caveat that my views do not reflect those of the United States Air Force. There is pushback from some and, if not hostility, skepticism about the security cooperation mission. Walk us through why security cooperation can be a controversial topic in some military circles.

DR: There’s a lot of pushback on the idea and a lot of it has to do with our performance in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. Without a doubt we could use the “f”-word, failure, in some of these places. I think there are three million veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, so their impressions of building partner capacity is based on their personal experience. We all know it is dissatisfying. At this point, the Iraqis should have had the capability to deal with the emergence of ISIS and bringing regional stability. The Afghans today are taking greater casualties than they were five years ago in spite of a hundred billion dollar effort to build their force.

So we have those experiences and then some positive experiences. If we want to compare industrial scale efforts, I would also raise South Korea because that was a rebuild effort from scratch in the 1950s and their military today is fantastic. If we look at another more recent small-scale effort, Plan Colombia began in the early 2000s with a modest amount of U.S personnel, training, and equipment like helicopters to build an air mobility command. Using that, the Colombian military brought their government from the brink of failure back to a great, strong, democratic, capitalist country.

But if we look more broadly one of the reasons why failure is going to be more common is that we are non-exclusive. That over the last 15 years we’ve tripled the number of Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs) from 40 to 120. If we look at funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) it’s doubled. Foreign Military Financing, where you can use U.S. grants to buy equipment, has more than doubled. We’re extremely non-exclusive and any time you take the non-exclusive approach and plant seeds everywhere, you’re not always going to get flowers. So there are probably going to be more failures than successes.

My answer to critics on this point is that it’s a foreign policy program. I know we want to measure outcomes based on what we think we’re doing and there’s always an effort to make armies, navies, and air forces better, but there is a foreign policy dimension to this that we cannot overlook. Sometimes what that means is we get a better relationship or the U.S. gets base access. There are clear cooperative benefits such as working with Japan and Israel on missile defense. That’s security cooperation too. It’s not just Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

MM: You’ve outlined why security cooperation is important and answered some of the skepticism about the mission. But how do you answer the broader question which came up during the last presidential election about the role of the military. I think there was a quote, at one point, that the military’s job is to “break stuff” and it should only be doing kinetic missions. How does the military, which is already overstretched with its current obligations, balance the kinetic mission with the security cooperation mission?

DR: This is an old idea. One of the inspirations for me was Marine General [Charles] Krulak and his experience in Somalia in the early 1990s. He talked about the three-block war where, at any one time, a Marine unit could be fighting, conducting peacekeeping, and conducting humanitarian assistance all at the same time. This is an important debate. I get pushback from both sides: the humanitarian community says “you’re militarizing foreign policy; this should be the work of NGOs, not military personnel.” My response is usually “I agree entirely and that is the preferred outcome” but in certain spaces where it is to dangerous for NGOs to operate, like Iraq and Afghanistan, you do find that the military is operating in those spaces.

From the military, I get the same sort of criticism that the U.S. military’s role is to fight and win the nation’s wars, kill people, and break things. And then I’ll usually highlight that the military is largely a logistics force. I think in the Army there is a 1:6 ratio of lethal trigger-puller to support. How I see security cooperation is: what are those six people doing when they’re not fighting war? The U.S. military has the largest logistics capability in the world. The U.S. military has the largest deployable medical capability in the world. So when President Obama wanted to respond to the Ebola crisis, he looked to the U.S. military because it could bring its own logistics and medical capability to help countries overcome the security deficit created by the disease.

Without a doubt it is controversial but it also goes into how do you conceptualize war. The kind of work I’ve been doing is really about how to prevent conflict. I think how you do that is through strength and partnership. My refrain is “even Switzerland flies the F-18.” It has more fighter aircraft than Nigeria does. Countries need a minimum level of national security both from a defense perspective, such as protecting their airspace, but also the internal perspective which deals more with policing.

MM: Walk us through a couple of other examples beyond Ebola, Iraq, and Afghanistan of how the U.S. has used its robust logistics capability for the security cooperation mission.

DR: Let me try to navalize this a bit.

MM: We are a maritime security podcast after all.

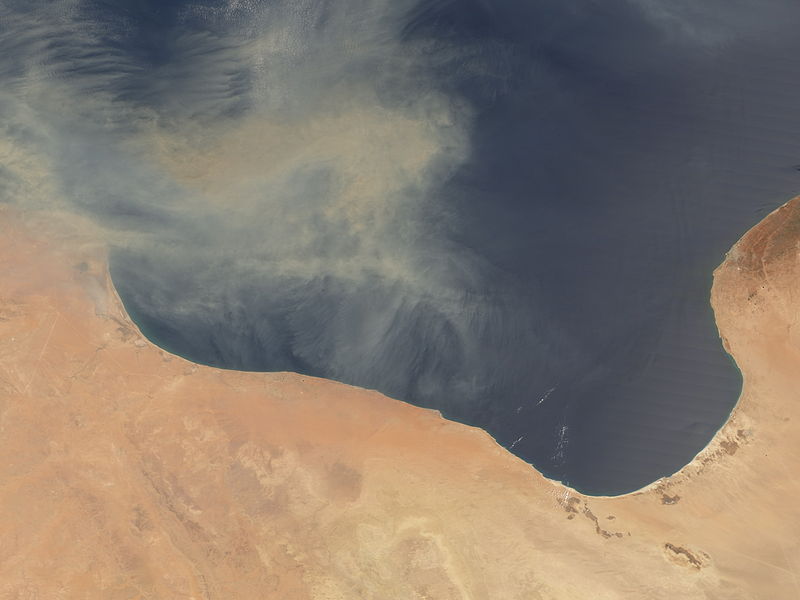

DR: I’m a Navy reservist but the irony is the two times I’ve been mobilized for deployments I’ve worked for the Army. So I probably have more insights there. The Navy is extremely embedded in the concept of security cooperation. For example, in the book I reference how in 2005 two thinkers, Admiral [John] Morgan and Admiral [Charles] Martoglio proposed the idea of the 1,000 ship Navy. It wasn’t 1,000 U.S.-flagged warships but it was the idea that the oceans are too big and too much maritime insecurity for one country to deal with it alone. The U.S. would instead use its logistics and intelligence capabilities to organize maritime coalitions. We see this today where three maritime coalitions are operating out of Bahrain that patrol the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Gulf, and those important waterways and chokepoints. That’s security cooperation: countries that are working together to reduce security deficits at sea.

We saw it pay off about a year ago when the U.S. had an aircraft carrier gap in the region, so France assumed command of CTF-50 and used the Charles DeGaulle, its aircraft carrier, as the lead strike element. That was possible because the U.S. and France and other navies in the region had already been exercising together and promoting interoperability. That’s something where the U.S. benefits along those lines. You look at bilateral relationships in Northeast Asia: for every F-35 South Korea or Japan buys, that’s one more in-theater the U.S. could have in a time of crisis or one less the U.S. would need to provide. Coalition warfare is the norm and we need to promote that through interoperability and information sharing.

MM: I’m glad we’re getting to the maritime dimension of this. In the maritime chapter of your book, you talk about some issues which most people don’t think about they think about the sea services. You talk about illegal fishing, piracy, trafficking, and pollution. What makes the maritime domain different for conducting security cooperation versus on the land and in the air? How do those issues you identify play into the Navy’s and the Coast Guard’s capabilities for dealing with these challenges?

DR: In general, I’m united about the idea of security deficits. Regardless of where it is, a security deficit is when a country lacks the ability to protect its national security without others’ help. And in this case other tends to be the United States because we are the largest military dollar-wise and very professional. The U.S. has no shortage of soft power; almost every country in the world wants U.S. attention. The source of the deficits change though. In Latin America on the ground, its transnational gangs and trafficking organizations. At sea in East Africa, it was maritime piracy but the deficit was on the land. The Somali government couldn’t control its water space and that created the deficit at sea which allowed the pirates to challenge commercial shipping.

Same thing with airspace. We take for granted in the U.S. that we have a good idea of what is happening in our airspace. That’s not true in many parts of the world, so the U.S. will promote air understanding through exporting radars and building command and control networks. At sea, we have to recognize that the U.S. Navy is focused on sea control and naval warfare but the other 100 or more navies and coast guards in the world aren’t. They are more concerned about migrant flow, illegal fishing, and maritime piracy. When the U.S. Navy wants to work with these countries, that’s where it has to meet them. They have to focus on what concerns them, not what concerns us. But I will also argue that, if we work together on how to combat maritime piracy, we can bring the same interoperability to a combat scenario.

MM: As you mentioned, a lot of the world’s navies are more like coast guards. What do you see as the proper balance between the roles of the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Coast Guard for doing the security cooperation mission? Should the Navy be more adept at dealing with law enforcement issues even though it’s not allowed to do them in the U.S.? Do you see the Coast Guard as having a larger role in the security cooperation mission despite its smaller size?

DR: I don’t want to upset some of your listeners by using the Grey Zone concept because I know it’s controversial but, by U.S. law, we want to separate war from police very cleanly. In general I agree that the Navy should lead in issues of war and the Coast Guard should lead in issues of law enforcement. What I have found in my reading of military history and personal military experience is that war and peace do not separate so neatly on the battlefield. What about when a drug trafficking organization uses a semi-submersible vehicle? Is that really a police problem or is it a Navy problem? In general, the Coast Guard does not practice anti-submarine warfare (ASW); the Navy does. It really depends. Would I want the Coast Guard to develop an anti-submarine warfare capability? I would say no because it’s time-consuming and expensive. But would it make sense for the Navy to do ASW during some of its build-ups? I’m more open-minded to that. Is there a shortage of vessels whether they are grey-hull [Navy] or white-hull [Coast Guard]? Absolutely. Is there any amount of vessels the U.S. can deploy to solve the gaps on its own? Absolutely not. That is why I think the global initiatives are important for U.S. national security.

MM: One of the ideas you discuss is the Global Fleet Station concept. Walk us through that. What is the concept, how does it work, and how has it been utilized so far?

DR: This is a small-scale attempt for the U.S. Navy to work with partners around the world. In Africa it’s called the Africa Partnership Station. In the Western Hemisphere, there’s a version called Southern Partnership Station. The Pacific has Pacific Partnership Station. It’s a mobile training platform, the Navy will go from port to port doing short courses. In many cases, you aren’t going to be able to solve the long-term security problems these nations have with a week’s worth of training. But it’s not intended to do that. It’s one way to supplement other security cooperation programs.

As a professor, I believe one learns best when teaching others. So the sailors, marines, and coast guardsmen who embark on these programs are teaching but they’re also learning. There’s been good efforts on the part of the Ghanaian and Nigerian navies to combat armed robbery at sea activity which has come through these training programs. I would start with being realistic on what the U.S. can actually do. I’ve got a good friend at Tulane who takes a more isolationist view of U.S. foreign policy. To him, we’re at a great point in our history: we’ve got a strong military and a strong economy, oceans to protect us, and safe neighbors, so we should pull back. If I could quote former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, he said “we can give them training, we can give them equipment, but we obviously can’t give them the will to fight. But if we give them training, we give them equipment, give them support, and give them some time, I hope they will have the will to fight.” I would say that’s broadly true. We can train and equip but we can’t give the will to fight. An outside actor like the United States can only have so much influence.

MM: Throughout the course of your research, you’ve given a great and detailed description of how the U.S. does the security cooperation mission. You also mentioned that the United States, for the most part, is the international partner of choice whether because we are a superpower or because we can be in more places due to our mastery of logistics. In your research, have you come across other ways of doing the security cooperation mission used by other countries, say what Japan is starting to do in Southeast Asia, the French support mission in Mali, or the nations operating under the NATO banner in Afghanistan? Are there other security cooperation models which you found interesting or noteworthy for our audience?

DR: I think in general other countries follow the U.S. model but, really, the U.S. doesn’t have a model. This is one of the criticisms: there is no one-size-fits-all approach where you can measure things. To me, that’s the right approach. I understand why people want to see performance measurements. But it’s a foreign policy program and not every project is going to be successful.

For example, the Chinese have replicated U.S. hospital ships that are doing medical diplomacy missions. They’ve replicated the idea of war colleges and staff colleges bringing foreign personnel to study. Let me use another successful example of Canada. Canada had been training Jamaican helicopter pilots for decades. They’d fly them up to Canada for training and it would be very expensive. So at one point they said they’d like the Jamaicans to be self-sufficient in this. So Canada helped stand up a helicopter training program so it could train its own pilots. But now what happened is that Jamaica became a regional center to train pilots from throughout the Caribbean and central america. And that to me is a great idea: put a training base in another country. That’s a lesson I think we could learn. We’ve done that with peacekeeping center. The other one with Plan Colombia.

The question you ask is ‘what do these countries look like when they graduate? Do these countries ever graduate?’ It is a foreign policy program so, for example, I don’t envision Israel ever graduating from the U.S. foreign assistance program. It’s an important relationship and in some ways it’s a two-way relationship such as through missile defense. But it’s also a U.S. foreign policy priority for Israel to have the strongest military in the region. In Colombia, their graduation is that they’re now training militaries from other parts of the hemisphere against drug traffickers and insurgents. To me that’s great news. It’s great that we have a long-term relationship with them but also that they are spreading out to train others to improve hemispheric security.

MM: So if you were president for a day and could move those bureaucratic levers, what would you do if you could make changes to how the U.S. security cooperation mission works? Would there be personnel changes, would you invest in certain technologies, would you put more resources or attention into certain regions? What would be your wish list for what you would like the U.S. to do to improve its security cooperation mission?

DR: The first thing would be to preserve and strengthen the dual-key approach. One of the concerns people have is militarizing foreign policy. Beginning with Secretary Clinton and Secretary Gates, they put in a dual-key approach that any program would need to be approved by both State and Defense. What I found working with different embassies around the world is ambassadors look at these programs as deliverables to their host government. All countries have national security challenges; even Switzerland buys the F-18. So we need to make sure we preserve that foreign policy dimension.

The second would be to look long term. We’re on annual budgets if we’re lucky but these programs take a long time to develop. As we know with our military it takes a decade or longer to get a senior NCO or mid-grade officers. So we need to be in less of a hurry. Finally, we need to embrace the idea that our partners’ failure is not our failure. I had to embrace this idea a bit when I was in Afghanistan. One of the problems with U.S. military culture is that can-do attitude which works wonders most of the time, but with security cooperation and assistance programs, we need to make sure the U.S. is not doing the work for others. That success is when they can stand on their own.

This strikes me as there is a little more patience today in Iraq, as you can see in General [Joseph] Votel’s testimony to Congress in the last few weeks. We’re moving at an Iraqi pace. I’m sure that’s frustrating for some who’d say that, if it was the U.S., we’d be done by now. But the point is what happens after ISIS is defeated. It’s the Iraqis are still there. They need to be the ones with the skill and investment in their national security.

MM: That’s a good point to start wrapping up. So, as is Sea Control tradition, what are you reading? What would you recommend to people who are interested in learning more about security cooperation or otherwise?

DR: I recently picked up Nadia Schadlow’s book War and the Art of Governance. I didn’t intend to read it fully because I had grading to do but I really liked her book. I thought it was sort of a bookend for my work. I look at phase zero, before combat activities, while Nadia looks at post-conflict and the important role that stability operations play in building foreign forces after conflict. Her work looks at how stability ops are a critical part of U.S. Army history and her bigger conclusion, which I find compelling, is that we suffer from a denial syndrome. That we still have this notion that wars look like what we see on the History Channel with victory in the Pacific or D-Day invasion and we don’t have documentaries on post-conflict reconstruction in Germany, Japan, South Korea, and the Balkans.

Beyond that, I’ve got a couple of my own book projects I’m working on including looking at the other side of this coin: what generates human insecurity. If you look at conflict data, the event where countries which invade other countries is pretty rare right now. Obviously you have examples like Russia and Ukraine, the U.S. and Iraq, Israel, and Lebanon. But there’s a lot of conflict in the world, at security below the state level with transnational actors. So I’ll be looking at that and how it generates U.S. foreign policy responses.

MM: I’ll take this opportunity to plug Exporting Security again on your behalf. I’m personally a big fan of the security cooperation mission and there’s not a whole lot of scholarship on it and I appreciate you writing about this mission which normally flies under the radar. Thank you for being on Sea Control, good luck with your book projects, and hopefully we can get you on another time to talk about your new research.

DR: Thank you for your time, Matt, and thank you for all of the work you guys are doing with CIMSEC. Keep promoting the importance of maritime security and promoting the role that navies play and making sure we can drink coffee in the morning.

Derek Reveron is a professor of national security affairs and the EMC Informationist Chair at the U.S. Naval War College and author of Exporting Security: International Engagement, Security Cooperation, and the Changing Face of the U.S. Military. These views are his own.

Matthew Merighi is the Senior Producer for Sea Control.