By Lieutenant Commander Daniel T. Murphy, USN

Introduction

“Was it over when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor?”1 – Bluto Blutarksy, Animal House, 1978.

Most Americans know that it was Japan, not Germany that treacherously attacked the U.S. Navy fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. A smaller percentage of people are aware of the fact that it was the United States, not Japan that fired the first shots of the war on that day. The destroyer USS WARD was patrolling near the entrance to Pearl Harbor when the minesweeper USS CONDOR reported a periscope at 0342. A PBY patrol plane placed a smoke marker on the location. WARD conducted a surface attack with guns, followed up with depth charges, and reported the sub sunk. The midget sub sunk by WARD was discovered by a University of Hawaii research submersible on August 28, 2002.2

It is true that WARD’s attack was a minor component in the bigger context of the Pearl Harbor attack. And, it does not materially change the fact that Japan was the belligerent on that day. But for sixty years, WARD’s story was de-emphasized in the historical commentary. Was WARD’s attack de-emphasized because it didn’t enhance the commentary of Japanese treachery? Or, was it because we did not have material evidence of the attack until the sub was located in 2002? Either way, it’s a minor detail, right?

Perhaps. The problem is that some of the “less-minor” strategic components of the story of the Pacific War have been de-emphasized as well. Because we (the United States) were the victors in the war, we have owned the historic narrative of the war. Our version of the Pacific War became the version of the Pacific War. “Vae Victis” (Woe to the vanquished).3

Our convenient and succinct story of the Pacific War was that Japan was hell-bent on conquest in the South Pacific. The United States only wanted peace. They raped Nanking. We initiated an oil embargo. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto crossed the Pacific with his carrier fleet and treacherously destroyed our battle fleet at Pearl Harbor. It is a convenient and succinct story, repeated by millions of soldiers, sailors, and citizens during the war and in the years after the war. But it is an incomplete narrative. Here are some less simple and less convenient ingredients in the story:

- Tokyo was executing a grand strategy that the United States had suggested to them. Japan was an aggressive state because, for quite a few years, we had encouraged them to be aggressive.

- For Japan, their naval war against the U.S. was a sideshow in a much bigger conflict on the Asian continent. In today’s U.S. military nomenclature, Japan’s Pacific operations would be called “ancillary” operations.

- If Tokyo had stayed true to its original Mahanian-based naval doctrine, Japan could possibly have defeated the United States in the Pacific War. Or, they could have at least achieved their political objectives.

Giant Dragons Puffing Smoke

Contrary to their representation in war-era and post-war-era film and media, Japan was not hell-bent on conquest simply because they were evil. Japan was seeking to build an empire in Asia because that is what the United States had encouraged and trained them to do.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, Japanese ports were closed to all but a few Dutch and Chinese traders. On July 8, 1853 Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay with a squadron of U.S. Navy vessels led by the USS POWHATAN. Perry’s “giant dragons puffing smoke” (steam ships) were intended to terrify. And in 1854, the United States and Japan signed a treaty agreeing that the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate would be opened to U.S. vessels to purchase coal and other supplies.4 For the U.S. it was a Mahanian play. The new coaling stations would enable our Navy to project seapower and protect our commercial sea lanes into the Asian continent. Japan would be America’s stepping stone to China, and the new ports would be especially useful for the American whaling fleet. In 1872, retired U.S. General Charles LeGendre traveled to Tokyo and first suggested to the Japanese that they should have their own Asian “Monroe Doctrine.” In the following years, LeGendre acted as a trusted advisor to Tokyo, encouraging the Japanese to take Taiwan and instigate the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. When Japan defeated Russia in the 1904-1905 war to extend Tokyo’s territories on the mainland, American magazine articles explained “Why We Favour Japan in the Present War” and “Russia stands for reaction and Japan for progress.” U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt felt an excited tingle for the Japanese victory. He told his friend Japanese Baron Kentaro Kaneko, “This is the greatest phenomenon the world has ever seen . . . I grew so excited that I myself became almost like a Japanese, and I could not attend to official duties.”5

When Japan invaded and took over Korea in 1910, U.S. foreign minister to Korea Horace Allen cabled to Washington that Tokyo had become Korea’s “rightful and natural overlord.”6 Roosevelt wrote to Secretary of State John Hay, “The Japs have played our game because they have played the game of civilized mankind . . . We may be of genuine service . . . in preventing interference to rob her of the fruits of her victory.”7 And in a letter to Vice President Taft he wrote, “I heartily agree with the Japanese terms of peace, insofar as they include Japan having control of Korea.”8

LeGendre’s Monroe Doctrine conversation with Tokyo continued thirty years later by Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft in 1905. Taft travelled to Tokyo to push the Monroe Doctrine idea with the Meiji emperor. Roosevelt pushed the idea with Japanese envoy Baron Kaneko Kentaro in Washington – “Japan is the only nation in Asia that understands the principles and methods of Western civilization . . . All the Asiatic nations are now faced with the urgent necessity of adjusting themselves to the present age. Japan should be their natural leader in that process, and their protector during the transition stage, much as the United States assumed the leadership of the American continent many years ago, and by means of the Monroe Doctrine, preserved the Latin American nations from European interference, while they were maturing their independence.”9 The American president had invited Tokyo to dominate her Asian neighbors. The U.S. had awakened a sleeping dragon to guard America’s open door to the Chinese continent. The dragon went on a fifteen-year fire-breathing shooting spree. And in 1940, Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka argued, “If the United States could rely upon the Monroe Doctrine to support its preeminent position in the Western Hemisphere in order to sustain American economic stability and prosperity, why could not Japan do the same with an Asian Monroe Doctrine?”10

Ancillary Lines

In the years leading up to 1941, while Japan certainly recognized the United States as a potential enemy, Tokyo’s number one foreign policy priority was China. An American military analyst named Hector Bywater wrote a fascinating book in 1925 about a fictional war between Japan and the United States touched off by a land dispute in China. Bywater said Japan’s “capitalists and merchants enjoyed a virtual monopoly in Southern Manchuria, besides holding a controlling interest in the mines, railways, and industries of Eastern Inner Mongolia…Even the coal and iron mines of the Yangtse Valley were exploited to a large extent by Japanese nationals…Without Chinese minerals her industrial machine could not be kept going; it required to be fed with a constant supply of the coal, iron, copper and tin from the mines of Shansi, Shantung and Manchuria.” Thus, for Japan, it was “essential that China should remain disunited and impotent.”11

Commodore Perry had gone to Tokyo with the idea of creating a stepping-stone to China. The assumption was that China would remain an “open door” to all nations. However, by the 1920s it was becoming clear that America had awakened a sleeping dragon. As Japan expanded her presence in Manchuria through 1932 and Mongolia through 1937, the U.S. and European governments worried that Tokyo was taking control of the open door. Without permission from Tokyo, the Japanese Army leaders initiated the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, which would eventually require thirty-six Japanese Army divisions. Stories of atrocities circulated around the globe, including the massacre of a quarter million Chinese civilians and disarmed soldiers in Nanking in 1937. The U.S. and Europe were running out of patience with Tokyo.

In the fight against the Japanese Army, Chinese forces imported arms and fuel through French Indochina, via the Sino-Vietnamese Railway. To sever China’s supply line, Japan invaded French Indochina in September 1940. In response, in 1940, the U.S. stopped selling oil to Japan. Japan had been reliant on the United States for more than eighty percent of its oil. The embargo would force Tokyo to decide between withdrawing from Indochina (a U.S. pre-condition) and negotiating or finding oil elsewhere. Ultimately, Japan determined to take the Dutch East Indies by force for its oil and rubber. The Netherlands had been defeated by Nazi Germany in May 1940, and was powerless to react. Tokyo expected the U.S. to respond with force, and therefore prepared for war.

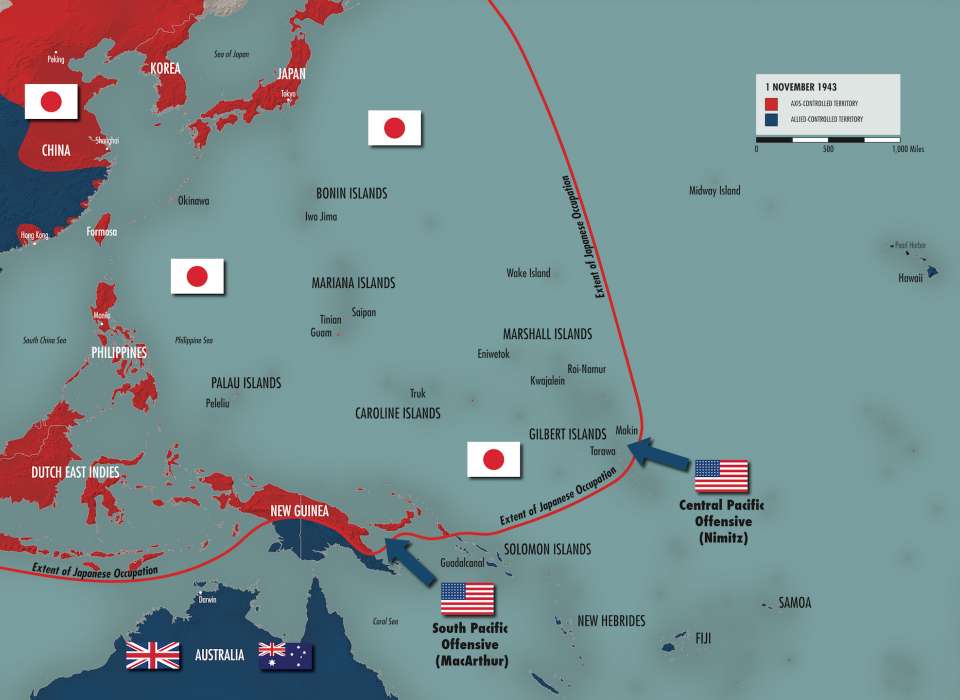

Thus, to continue to fight their primary war over minerals, foodstuffs, and other natural resources on the Asian mainland, Japan was forced to initiate a secondary war (A series of secondary operations that today’s U.S. planners would call “ancillary lines” 12) against the U.S. to secure the new energy resources in the Dutch East Indies and the rest of its Asian conquests. China remained the primary adversary. The U.S fleet would become the secondary adversary. Protecting those ancillary lines meant denying the U.S.’s ability to stage operations against those lines. Thus, Tokyo adopted its perimeter defense strategy which required the invasion and fortification of island chains from the Kurile Islands in the north through the Philippines and all the way south to New Guinea.13 In other words, the strategy was to protect the new resource areas by occupying the islands adjacent to those areas and in the sea lines between those areas and the home islands. In the geometry of war, Japan would have the advantage of short, more easily re-enforceable lines of operations (LOOs), and the U.S. would have the disadvantage of longer, vulnerable LOOs. Ultimately however, the U.S. was able to negate that advantage through fleet size and sea control that consistently crept west.

Mahan With a Dash of Clausewitz

The Russo-Japanese War ended in 1905 with Tokyo feeling slighted. Japan had defeated Russia on land and at sea, and had helped secure the open door for itself and for the West to the “teeming Yangtze Valley.”14 But while Roosevelt and other European leaders said positive things about the Japanese victory, they pressured Tokyo to accept a negotiated settlement with Russia that did not include a war indemnity. Roosevelt’s honorary Aryans15 felt humiliated. Relations between the U.S. and Japan would grow worse. In 1906, struggling to deal with a wave of Japanese immigration into San Francisco, the San Francisco school board segregated Japanese students. Tokyo cried foul. American journalists wrote about a “yellow peril.” And in 1907, Roosevelt sent Admiral Dewey and the Great White Fleet around the world to wave the big stick. Japan viewed Dewey’s cruise as a direct threat. California then passed an alien land law in 1913 prohibiting “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural land that caused the U.S.-Japanese relationship to degrade further. By 1916, Japan’s naval operations chief stated, “The nation with who a clash of arms is most likely in the near future is the United States.”16

As the U.S. Navy became probable adversary number one, Tokyo began thinking in terms of Mahanian doctrine. From 1904 through 1930, naval strategist Ogasawara Naganari taught Mahanian concepts at Japan’s Naval War College. Akiyama Saneyuki, the “father of modern Japanese naval strategy” visited Mahan twice in New York, and incorporated his principles into Japan’s Naval Battle Instructions of 1910. Akiyama created Japan’s strategy of “interceptive operations” which would consist of the Japanese fleet lying in wait for the American fleet to reach Japan’s home waters and then “engaging in a Mahanian encounter.”17 Kato Kanji served as president of the Naval War College in 1920, Second Fleet Commander (1923-1924), Combined Fleet Commander (1926-1928), Chief of the Naval General Staff (1930) and Supreme Military Councilor (1930-1935). He used Mahanian doctrine as the basis to justify the naval budget and the expansion of the fleet.18

Japan embraced a Mahanian doctrine to counter the U.S. because they had proven the doctrine against Russia. At the Battle of Tsushima, on the 27th and 28th of May 1905, the Japanese Navy annihilated the Russian Navy, sinking thirty-five of thirty-eight ships, killing 5,000 sailors and taking more than 7,000 prisoners. Japan lost only 110 sailors.19 Between 1908 and 1911, the Japanese Navy conducted studies and war games focusing specifically on a conflict with the U.S. fleet as the adversary. Japan would capture Luzon Island in the Philippines, defeat U.S. forces there, and occupy Manila. They would lie in wait for the American battle fleet to cross the Pacific. When the U.S. fleet approached home waters, they would be annihilated in a decisive battle west of the Bonins, as the Russians had been annihilated at Tsushima. Japan would have the strategic advantage with their short interior lines of operation to their home islands. This was the interceptive operational strategy that the Japanese Navy would maintain through 1941 and beyond.20

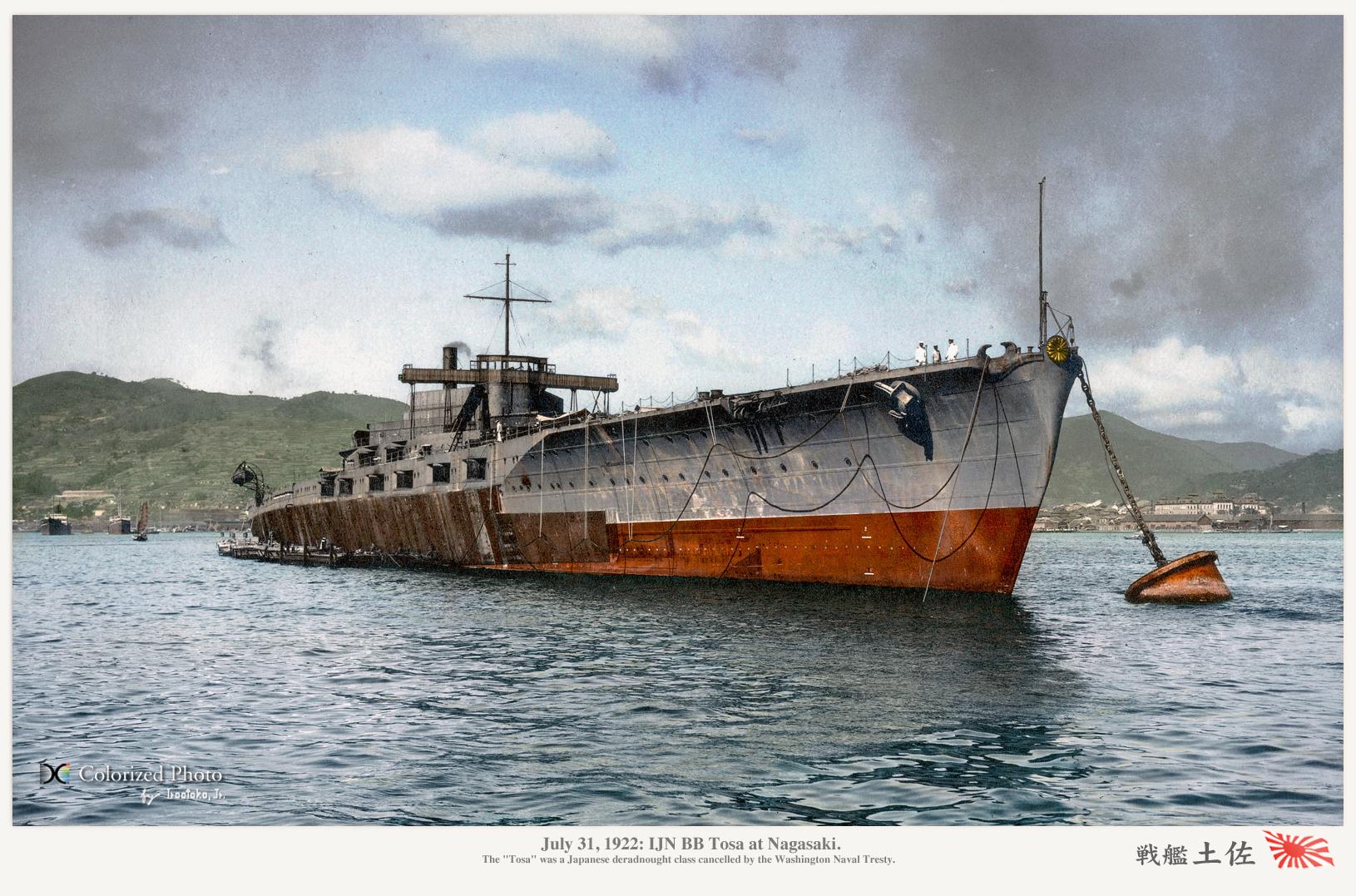

After Germany was defeated in the First World War, Japan occupied Germany’s possessions in the South Pacific – the Marshalls, the Carolines, and the Marianas. Accordingly, Tokyo’s new General Plan for Strategy in 1918 pushed the planned decisive engagement with the U.S. fleet eastward. The Tsushima replay would now occur somewhere west of the Marshalls.21 But the greater challenge for Tokyo was the buildup of the U.S. fleet in the Pacific. It was an arms race that the U.S. did not really want, and that Japan could not really afford. In 1922, Japan signed the Five Power Naval Treaty at the Washington Conference and agreed to a 6:10 capital ship ratio with the United States.

The extended island possessions plus the 6:10 capital ship constraint caused Tokyo to add an additional ingredient to their interception operations strategy. The 6:10 ratio meant that the Japanese fleet could not take on the U.S. fleet equally in a Mahanian battle without first cutting the U.S. fleet down to a fightable size. In Bywater’s fictional tale, Japan detonated an explosive-laden merchant ship to collapse the Panama Canal so that America’s Atlantic and Pacific fleets could not join forces.22 In the real world, to create parity, Japan again looked back at the Battle of Tsushima, and opted to inject a Clausewitzian ingredient into the Mahanian recipe.

In April 1904, Rear Admiral Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky took a considerable portion of Russia’s Baltic fleet on an 18,000-mile journey to fight the Japanese Navy in the Pacific. Rozhestvensky’s passage was filled with what Clausewitz would call frictional events.23 Things went bad early when an intelligence failure in the North Sea caused the Russian fleet to mistakenly open fire on a British fishing fleet. In response, British, French, and Portuguese ports were closed to the Russian fleet for the majority of their passage. They were forced to re-coal in the open ocean or in anchorages along the way. The lack of supplies, lack of shore leave, irregular mail delivery, and the heat of the tropics took a further toll on the equipment and crews – “Malaria, dysentery, tuberculosis, boils, mental derangement, prickly heat, fungoid infections of the ear, wrought havoc”24 in the fleet. Like how Napoleon’s and Hitler’s land forces suffered the effects of attrition (Clausewitz’s friction) in their marches to the east, Rozhestvensky’s fleet suffered similar effects of attrition in its passage to the east. Rozhestvensky’s degraded fleet was then wiped out in the great Mahanian battle on 27-28 May 1905.

To make up for the 6:10 capital ship disadvantage against the United States, Tokyo opted to create similar conditions of friction for the U.S. fleet. Japan’s new attrition doctrine would focus on submarines, cruisers, destroyers, torpedoes, and land-based and ship-based aircraft that would gradually degrade the U.S. fleet as it transited west across the Pacific. After the American fleet had been cut down to a more equitable size, the Japanese battle fleet would come forth to deliver the Mahanian coup de grace.25

Thus, after the Washington Conference, the Japanese Navy began building large, high-speed fleet submarines. By the early 1930s, Tokyo was building 2,200-ton 23-knot submarines. Admiral Suetsugo said, “The decisive battle would entirely depend on our attrition [submarine] strategy.”26 In addition to the submarine enhancements, light cruisers and destroyers were re-organized into torpedo squadrons and trained for night attacks.27 New cruiser and destroyer designs (Yubari, Furutaka, Myoko, Takao, Mogami and Fubuki) were introduced in the 1920s and 1930s along with a new Type 93 oxygen torpedo that had a range of 40,000 meters and a speed of 36 knots.28 Japan constructed the 30,000-ton (Akagi) and 38,200-ton (Kaga) carriers in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the carrier-based Type 94 “Susie” bomber and the land-based Type 96 “Nell” bomber. By December 1941, Japan’s navy had ten carriers and 3,300 aircraft, all intended to be used in the interception-attrition strategy against the U.S. fleet.29 The Mahanian coupe de grace would now be delivered by the new 64,000-ton Yamato-class battleships, which would use the greater range of their 18-inch guns to destroy the U.S. battle fleet from afar.30

Mismanaging the Trinity

A Mahanian strategy with a dash of Clausewitz could possibly have worked. Naval War College professor Brad Lee explained Japan’s interception-attrition strategy in terms of Clausewitz’s trinity. First, a naval victory against the U.S. fleet would degrade the U.S.’s ability to project military power in the Asia-Pacific region. Second, the defeat would affect public option in the United States, and “cripple America’s will to keep fighting.”31 The American people would settle on isolationism, or at least demand a Europe-first strategy. Third, the defeat would drive a wedge between the American president (Roosevelt) and the Congress, and degrade government consensus for a war in the Pacific. In the end, Tokyo hoped to be left alone to consolidate its gains in Asia.32

The Trinitarian strategy made sense. However, in 1941, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto added a final ingredient to the mix that changed the equation. Yamamoto did not want to allow the United States to trade space for time. He knew that invading the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, and Singapore would draw an American naval response. But what if the U.S. opted to delay their response for a year or two until their fleet was sufficiently augmented by its new shipbuilding programs? Like Napoleon and Hitler, Yamamoto wanted to fight the decisive battle earlier, rather than later, while he held numerical superiority in the Pacific. Thus, in 1941, he added the Pearl Harbor operation to the operational mix.

In the end, the Pearl Harbor attack did temporarily degrade America’s ability to project power in the Pacific (the military dimension of Clausewitz’s trinity). But the attack had the opposite of Yamamoto’s intended effects on the people and governmental dimensions. On December 8th, the American people demanded war. The U.S. president asked for a declaration of war and demanded unconditional surrender. The House of Representatives voted 388 to 1, and the Senate voted 82 to 0 in favor of war against Japan.

Conclusion

“Were we better than the Japanese, or just luckier?”33 – Henry Fonda as Admiral Nimitz in Midway.

The historical narrative of a war is written by the war’s victor. And that narrative is too often kept simple and convenient. This is something we must keep in our minds as we seek to learn from past conflicts. To learn from the Pacific War, we must beware the cursory narratives of that conflict: That Japan was hell-bent on conquest in Asia for no apparent reason, while we only wanted peace; That the Japanese were sneaky, but we were honorable; That they were wrong and we were right.

Dig a bit deeper into the historical detail, and we see that, while it is true that Japan was an aggressive state hell-bent on conquest, we helped them formulate their strategy and encouraged their imperial designs. If Yamamoto had not added the Pearl Harbor attack to his operational mix, would the American people and the U.S. Congress have opted to fight a major war on faraway shores?

Understanding the wartime strategies of our past adversaries can help us better understand the strategies of today’s adversaries. Again, the challenge is to push beyond cursory. Do we reflect on things we have done in previous decades that could have caused an ally to become an adversary? Do we consider the fact that an adversary might consider us to be their Priority Two, rather than their Priority One? Do we give our adversaries sufficient credit for employing whole-of-government strategies? How often do we think about how an adversary (or a so-called ally) will seek to inject conditions of friction into our operations?

The Pacific War became inevitable when the United States assumed Japan would come to the negotiating table, rather than choosing war. Japan’s disastrous end became inevitable when they assumed that an attack on U.S. soil would not awaken a giant force, or at least degrade it sufficiently to render it militarily impotent. If the U.S. and Japan had both dug deeper into the strategic landscape, the conflict may have been avoided or de-escalated. Perhaps the U.S. would have realized that there was no chance that Tokyo would negotiate for oil. Perhaps Tokyo would have realized that America’s pivot from isolationism would be fast and terrible.

Daniel T. Murphy is a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy, currently serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence. In his civilian career he is a full-time professor at Massachusetts Maritime Academy, and an adjunct faculty member at Northeastern University. Lieutenant Commander Murphy earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Massachusetts, and master’s degrees from Georgetown University and from the National Intelligence University.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, or the U.S. Government.

References

[1] National Lampoon’s Animal House, directed by John Landis, Universal Pictures, 1978.

[2] “Researchers find 1941 Japanese midget sub off Pearl Harbor,” School of Ocean & Earth Science & Technology website, http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/SOEST_News/PressReleases/Japanese%20mini%20sub.htm, (accessed April 11, 2012).

[3] Said by Brennus the Gaul when he sacked Rome in 390 B.C., Livy, in Ab Urbe Condita (Book 5 Sections 34–49).

[4] “Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan,” U.S. Navy Museum website, http://www.history.navy.mil/branches/teach/ends/opening.htm (accessed April 29, 2012).

[5] James Bradley, The Imperial Cruise: A Secret History of Empire and War New York: Little Brown and Company, 2009), 236.

[6] Bradley, 227.

[7] Bradley, 226.

[8] Bradley, 223.

[9] Bradley, 217.

[10] Bradley, 319.

[11] Hector Bywater, The Great Pacific War: A History of the American-Japanese Campaign of 1931-1933 (Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1925), 2.

[12] Milan Vego, Joint Operational Warfare: Theory and Practice (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 2009), IV-64 and 65.

[13] James B. Wood, Japanese Military Strategy in the Pacific War: Was Defeat Inevitable? (Lahnam, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, 24-27.

[14] Sadao Asada, From Mahan to Pearl Harbor: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006), 15.

[15] Bradley 300-319.

[16] Asada, 52.

[17] Asada, 32.

[18] Asada, 52.

[19] Shannon R. Butler, “Voyage to Tsushima,” Naval History (Annapolis: United States Naval Institute), June 2012, 58.

[20] Asada, 50.

[21] Asada, 55.

[22] Bywater, 22.

[23] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. and eds. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967) 119.

[24] Butler, 63.

[25] Asada, 103.

[26] Asada, 180.

[27] Yoichi Hirama, “Japanese Naval Preparations for World War II,” Naval War College Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, Spring 1991, 66.

[28] Hirama, 68.

[29] Hirama, 69-70.

[30] Asada, 205.

[31] Asada, 182.

[32] Brad Lee Lecture.

[33] Midway, directed by Jack Smight, Columbia Pictures, 1976, Henry Fonda playing Admiral Chester Nimitz in the final scene.

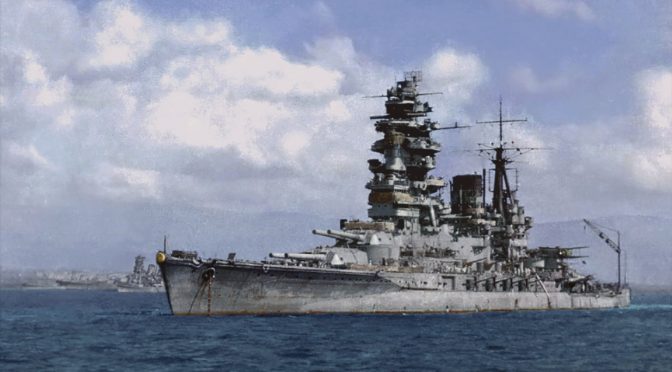

Featured Image: (October 21, 1944) IJN battleship Nagato at anchor in Brunei. (colorized by Irootoko Jr.)