By Chris O’Connor

Ma’am, your presence is requested in Combat. OS2 Van-Manama’s message appeared in the right lens of LCDR Sara Fernandez’s glasses. A top-down overlay of an unknown surface contact appeared in her left lens.

On my way, OS2. She subvocalized back. She still wasn’t used to the formality in the Navy. Or the food. The only thing she ate for breakfast in this hot weather was buttered toast. She got up from her seat in the tiny mess space, dropped her plate in the washer, and went down the ladder.

“What do you have for me?” She asked OS2 V-M as she entered the Combat Information Center. She could talk plainly here. No need to message through LiFi to communicate, as she did in the rest of the ship. Combat was not an impressive space; two terminals, an observation chair, and display wall. At least it was air conditioned. OS2 was seated at the right terminal.

“It’s that Contact of Interest we’ve been waiting for; 350 at 23 miles. Going 13 knots on a course of 170. It’ll pass right by the seafarm.”

She squeezed past OS2 to sit at the left terminal and pulled up the COI’s track info. It was classified on AIS as a fishing fleet factory ship. The Chinese had this type harvesting seafood in every ocean now that most fisheries in their EEZ had collapsed.

V-M continued. “Its signature is certainly correct, the right number of diesels at the right harmonics, ELINT shows commercial SATCOMs and surface search. And the satellite images we pulled down show a wake profile that fits for a ship of the type. It has one commercial VTOL security drone up. I’m sure it’s aware of our tender.”

“Copy. I’ll go let the Captain know.” She said, leaving Combat.

The Master, Captain Aquino, was on the port bridge wing, observing crane ops. The heat and humidity was mitigated by a slight breeze. The Polillo 2 was working on one of the seafarm perimeter buoys.

“Morning, Captain.”

“Morning.” He mumbled back, eyes remaining on the crane. “I see the large contact on the Furuno. Is that why you’re here?”

“You guessed it. After this buoy, could you secure from crane ops for a while? We should be prepared to maneuver.” Fernandez said.

“I know the drill.” Aquino said, annoyance creeping into his voice. “I’ll go to thrusters soon and be ready to seem really interested in working deep in the buoy field.” He said, gesturing out to the farm, large yellow solar floats extending south as far as the eye could see. “I’ll act casual, ‘cuz I don’t want to be killed.”

“Yes, Sir.” She said, heading for the ladder.

“Don’t call me Sir!” He shouted after her. “I was a Senior Chief in the Navy. And I STILL work for a living!”

_______________________________________

A disembodied voice greeted Sara. “Thanks for coming today. The purpose of this interview is to collect information for our historical archives.” All that she could see was the emblem for Naval History and Heritage Command floating six feet in front of her in an empty, white-paneled cube. It was the default setting for a VRcast waiting room.

“Coming today? I’m in my office at home,” she pointed out.

“We will set the default interview template.” The view faded and was replaced by a mid-twentieth century history professor’s study, complete with walls of bookshelves and leather chairs. Fernandez could almost smell books, old wood, and leather. But without a multisensory neural link, it was all in her imagination.

Across from her was a desk covered in papers. Seated behind it was a middle-aged man, hair thinning on top of his head and in a blazer with leather patches at the elbows. A notepad was ready in front of him, fountain pen in hand.

“Does this put you at ease? We can set this to any template you prefer.” The interviewer AI asked, now enrobed in a professor avatar.

“This works for me. It is kinda funny, though. I was never in an office like this because I am not 100 years old.”

“Alright, then. Let us get started. The purpose of this interview is to collect information from veterans of the war so that we can make VR historical simulations. It is intended as a free-flowing discussion. I detect that you have a brain interface implant. Can we access it for biofeedback during our talk?”

“No, it’s just an augment for my right eye.” Sara felt an itching sensation where flesh and bone met metal and plastic in her ocular cavity. Maybe it was time for a firmware update.

“Joined the Navy at 36, after a leaving a successful career in autonomous systems. You were being paid more than two times a Lieutenant Commander in your civilian job. There were many people in your comfortable position that did not join up when the nation needed them. Why did you?”

_______________________________________

“The seafarm surveillance drone that US1 reconfigured is making an ID pass.” OS2 said looking at the drone feed. “Something’s not right.”

LCDR Fernandez was sitting in the chair next to him and monitoring the sensor feeds, while watching the AI run the object detector module. They had to use laser to communicate with the drone to keep their comms signature down. Signal strength was not very good in the humid and salty conditions.

The video feed from the drone showed the COI. It was painted blue and white, with perfectly placed rust streaks, and the superstructure was not quite right to Sara. The detector results came back as possibilities: 95% factory fishing ship, 72% car ferry, 5% generic amphibious warfare vessel. On the visual feed, panels on the side of the COI were changing colors, sometimes flashing patterns.

“It looks like it is covered in active adversarial network patches. I’ve never seen so many,” V-M said. “Our module is only seeing a fishing vessel and somehow ignoring the other qualities of the ship. It is being played like a fiddle.”

“Do you think they know the standard detector module inside and out and trained their AN systems to counter it?” Sara said sarcastically. “OCEANUS,” she said to the Combat AI. “Run it again with that algorithm trained with US1’s input set. A new module that the Chinese did not plan to encounter might see something else.”

After a few seconds, the module came up with a new result. 94% modified Type 071 (NATO reporting name: Yuzhao) LPD.

It was a Yuzhao altered to have the external appearance of a fishing vessel. It could have been damaged in the opening of the war and rebuilt in the yards to look that way. Maybe it was a mod of one of the export variants that never made it to Thailand.

Either way, it was a major violation of the Seven Powers agreement. Warships of that size should not be in the South China Sea.

_______________________________________

“I was a domestic delivery drone network supervisor. Studied robotics at Carnegie Mellon and got hired right after graduation by a small logistics UAV startup in San Diego. After working there for a few years, the company was bought out by one of the tech companies, which was inevitable. Absorbed into the workforce of a FANG, I was responsible for all UGV and UAV delivery operations in Pennsylvania when the war started. Looking back, the strangest part of the whole thing was we still haven’t figured out who started what we now call the ‘Seven Powers War.’”

“What do you mean?” The interviewer said, now going through the motion of jotting down notes.

“We always blamed China for starting the war, and China blames us. But neither of us were ready at the kickoff. The CCP was hit by that massive ransomware attack at the same time as Congress and the White House. And it was a well-executed hit job. Almost everyone’s official and personal email accounts and phones were taken offline, with no way to pay it off, like the NotPetya attack back in the day.”

“NotPetya?” The AI stopped writing.

“You don’t know what that is? You do real-time research while we are talking. I’m sure you know precisely what happened.”

“Of course, I will develop VRcast content with embedded branches to references. But for the sake of archiving the interviews for public consumption, I would like to do this as a conversation.”

“I am impressed how well you can talk to me. Can’t even tell that you are a bot.” Fernandez said.

“Ever since GPT5, the Turing test is invalid. If it would make you feel better, I can take on his persona for this interview.”

“Would you look like a young Cumberbatch or the real guy?”

“I can look like anyone you want if it makes this interview productive, but please do not call me a ‘bot.’ I find that outdated slang derogatory,” the AI said coldly.

“Right. Sorry.” She conceded. “I’ll get back on track. That attack’s intent was to cripple the leadership in both countries. Russia and the other powers either reacted quick enough to prevent it or they were not targeted. Of course, deepfakes of everyone taking credit were out there. I even saw one of Uruguay’s Prime Minister claiming responsibility to bring the ‘Great Powers to their knees.’”

“How did this lead to you signing on the dotted line?” the AI said, with a pipe now placed in the corner of his mouth, face simulating deep interest in the conversation.

Sara leaned back in her chair. “It’s a funny phrase, by the way. I completed my contract with a biometric finger scan.”

“I have to keep in character with my persona.” The AI commented, waving his pipe at his paper-covered desk. “I cannot be anachronistic.”

“Well, it was China’s first shots that made it personal for me,” Sara said. “They had been getting increasingly paranoid and thought we were intentionally crippling their leadership with the cyberattack. Maybe they thought we were overacting to that election-year PLAN carrier strike group FONOPS in the Gulf of Mexico. A lot of Americans were pissed off when the Chinese did that.

“Predicting a U.S. play in the Western Pacific, the Chinese leadership reacted with a what I see as a ‘flexible response option’— or at least that’s how my joint training would describe it. Instead of attacking our bases and combatants directly, they went for our fleet replenishment ships.

“Our oilers were easy to find and track with pretty basic AI, thanks to the hundreds of commercial imagery CubeSats in orbit. All the oilers underway in the Western Pacific had two antiship ballistic missiles fired at them. Not even the new missiles, but the older models, since our replenishment ships were easy pickings with no countermeasures or defenses. The PLA saved the new ‘DFs’ for the potential higher-end targets.

“Out of ASBM reach was USNS Genesee, two days west of Pearl. First in a new class of fast replenishment oilers, ‘Genny’ was the fastest and largest ship since the old AOEs were in service, with expanded hangar space for the new VTOL ‘Hopper’ logistics drones.

“Like its counterparts, it was sailing solo with no escorts. While its counterparts were being wiped out by ballistic missiles, the ‘Genny’ lost power. From what the survivors told us, immediately after a logistics database update, a worm was triggered in its power systems that shut everything down, to include backup batteries and generators. There was no recovering with the personnel onboard. None of their servers worked, so it was impossible to use the smart ship system to even find where the issues were.

“My Uncle Juan was one of the unfortunate engineers furtively trying to get the controllers on the diesels working when the main spaces and Hold 3 were both hit with sprint vehicles. Only nine from the crew of eighty-seven were plucked from the water hours later, after the UUV that launched the YJ-18s was found and neutralized.

“There were now no replenishment ships west of Pearl Harbor. They could have been crippled with worm attacks alone, but China put them on the bottom of the ocean. It meant that our warships throughout the Pacific had limited legs and were constrained to ports that were now at threatened by more long-range weapons.”

“So you joined because your uncle was killed?” The professor asked.

“It was a major part of it. We were not a military family. I had a great uncle that was an officer in the Navy during what he called the ‘Tanker Wars’ and my mom’s cousin served in the Space Force, but I really liked Uncle Juan and wanted to do something in his honor. The nature of how the war changed also made me a good officer candidate.”

_______________________________________

“Pass this info to the Hughes through the seafarm’s network.”

“Aye aye, Ma’am.” OS2 said. “US1 is putting up another drone to act as a laser comms relay for the exploit ops.”

“Ready for that?” Fernandez said to CTR2 Cruz. She was sitting in the left console seat now. Fernandez had moved back to the observation chair.

“Yes Ma’am. We have a common system target set fed into our JANUS AI. We’ll be looking for networks common to Yuzhaos, fishing vessels, or anything commercial commonly installed at the shipyard of origin.”

Sara reached behind her and grabbled the IC phone off the hook. “Captain, OIC. We’re about to annoy the contact,” she said.

“Copy,” Aquino gruffly said. “I’m turning off all my external comms and navigation systems except for the Furuno. It’s the only thing we have that is airgapped. Moving into the field now.”

The diesel vibrations through the hull stopped, and Fernandez felt the ship move on thrusters into the field.

“Sweep is negative for EM leakage. COI is doing a good job with signal discipline, save the nav radar.” OS2 reported.

“Let the Hughes know that we are going for network intrusion. We’ll probably get a response.”

“Will do Ma’am,” V-M replied.

“Let’s see if they left any of their antennas to receive only.” CTR2 said.

Probing low power signal antenna. JANUS began.

Detected: Autonomous trawling net system.

“It looks like they were serious enough about their cover that they put a commercial fishing system onboard, and someone didn’t think to disable the antenna.” Cruz observed.

Trawling systems connected to ship’s common servers.

Uploading worm.

Intrusion Detection AI on PLAN network countering.

Lost comms. JANUS was in the LPD’s network for mere seconds.

“Drone down.” OS2 said. “It looks like COI hit it with a laser.”

“Was the worm fully uploaded?” Fernandez asked.

Cruz was looking at multiple feeds at once, using hand gestures to make selections. “Looks like it, Ma’am,” she said. “It depends on which one JANUS decided to use.”

“They detected the intrusion, so it doesn’t have a lot of time to work,” Sara said. “What worm did JANUS deploy?”

Unmask Rev 11, JANUS responded, before Cruz could.

CTR2 continued. “The results from ‘Unmask’ will depend on how the shipboard networks are configu—crap!”

“Multiple military comms and radars radiating on COI. Classify contact as hostile!” OS2 shouted. “They just lit up like a Christmas tree.”

The true nature of the contact was now broadcast for the world to see. 27 miles away, on the west edge of the buoy field, the Hughes and its flotilla of Lake-class corvettes leapt to all ahead full, as their smaller Fiberclad USV escorts struggled to keep up.

_______________________________________

“The Navy needed people of your expertise with the new drone systems after the ceasefire,” the AI stated, leaning back in its chair, as if it was a human realizing this for the first time.

“Exactly. I’m sure you are collecting interviews from many vets, but as you know, the first two weeks of shooting was a free-for-all. It escalated so quickly that I am amazed to this day we didn’t go nuclear. I think it’s because we didn’t attack targets on the Chinese mainland, even though they laid waste to our Guam bases. China could have put some cruise missiles into Pearl or San Diego but chose not to. And both sides only used hypersonic weapons against each other’s warships. But that still meant that we lost a lot of ships. This wasn’t a one-sided exchange. With the help of the Air Force, we took out most of the larger platforms in the PLAN South- and East- Seas Fleets.

“We learned quickly that nothing on the surface of the ocean could hide anymore. On day one of the shooting, for example, they fired about thirty older ASBMs at the strike group that was east of the Philippines, purposely encircling it with impact points, demonstrating to us that they knew where it was.”

“Undeterred, our response to the sinking of the oilers was that same CSG launching a strike on Chinese artificial islands in the SCS. Before those strike aircraft recovered to the CVN, the CSG was hammered with ASBMs and long-range cruise missiles, and only the McCain got away without major damage. She escorted the survivors of the CSG into Tacloban; one barely afloat DDG and the CVN, which was missing sections of her island and had massive holes in her flight deck. The other strike group in WESTPAC had to fight its way back to Pearl through a PLAN UUV wolfpack, with a pod of our own ORCAs and LIVYATANs running interference.”

The AI was tearing through his notepad now; Sara wondered what exactly he was writing. The professor noted, “After this continued for two weeks, both sides ran out of chess pieces in the Pacific. And the Seven Powers ceasefire agreement limited the size of assets we could send over there.”

“The USN had to reconstitute fast,” she said. “It went on a crash course in platform procurement, and acquired small vessels built in yacht and fishing boat yards throughout the U.S. Most of these were modified to become unmanned surface vehicles. The USVs ranged from high-end combat ones, like the stealthy Fiberclads, to low-end logistics, surveillance, and lily pads for the short-range aerial systems. They were designed to need smaller logistical footprints so they could operate without a replenishment fleet of larger ships.”

“And new sailors were needed to crew this Navy,” the AI pointed out.

“Yep. It took about a year to get out to the fleet with my accelerated commission. Familiarization didn’t take too long. After all, I was experienced with a lot of the commercial platforms the Navy had bought. I joined up with the command in San Diego. Had sims and tactics training and was then assigned to a SCS-centric detachment that was to go underway on clandestine collection platforms. I thought the Navy was going to put me in charge of a sexy drone warfare unit. I ended up doing something quite different.”

_______________________________________

“Seneca just got hit.” V-M said calmly. “Most likely a UUV.”

“At least hiding in the farm will protect us from that.” Fernandez said, matter-of-factly. It would be hard to weave a weapon through the underwater maze of interconnected buoys to hit Polillo 2.

Now that the game was up, the Yuzhao was in survival mode. The radiating triggered by ‘Unmask’ abruptly ceased, and she increased speed and turned to the north, trying to bug out.

“Swarm deployment on hostile.” OS2 reported. Concealed launchers on the Chinese ship began to disgorge a heterogenous cloud of drones into the air around it.

The U.S. flotilla was not going to let that LPD live to sneak around another day. The surviving corvettes each launched a pair of Super-LRASMs at the contact while kicking out their own much smaller swarms, which included Cormorant UAVs to counter the hostiles in the water below.

None of the LRASMs reached their target. They met a brick wall of drones, directed energy, and good old fashioned 30mm CIWS rounds. But the Hughes drove on with the flotilla, firing the rest of their missiles and going ‘Empty Quiver.’ The flotilla put every available drone into the fight, emptying their launchers. The LPD was more than a match. The PLAN equipped it with a superior combat systems AI and scores of drone tubes.

OS2 unleashed creative stream of multilingual invectives. Fernandez was impressed how her comms AI tried to keep up with the translation, labelling it as Mix of Vietnamese and Kiro. One insult, for example, had something to do with a whale and a bowl of petunias.

“I don’t know what you are saying, but it doesn’t seem professional,” she said.

“Sorry Ma’am. The contact just went Death Blossom on us,” V-M muttered.

The classic movie reference would have been funny in any other context, but the video feed of the LPD putting up an ever-thickening cloud of UAVs like an angry beehive was no laughing matter. To make matters worse, drone variants were launched that were new to OCEANUS’ threat database.

CTR2 barely croaked, “Network sweep. They suspect us. JANUS is countering multiple intrusion attempts from the Yuzhao through the seafarm net.”

Then Sara saw on the OCEANUS feed a tendril of the enemy swarm break off and head toward Polillo 2.

_______________________________________

“We were assigned to a 32-meter buoy tender, based out of a small fishing port in the western Philippines.” Fernandez continued. “There were many commercial vessels like it, contracted out to maintain farms of aquaculture such as kelp and mussels. We bounced around geographic locations in the SCS based on collection requirements. The Det consisted of seven ununiformed sailors of a mix of rates: Operations Specialists, Unmanned Systems Techs, Cryptologic Techs, Additive Artisans. I was the Officer in Charge, but the tender’s Master was a Merchant Mariner.

“These tenders were set up for autonomous systems control and maintenance. Seafarms are run on a daily basis by a workforce of aerial, surface, and subsurface drones that check the buoys’ status, scan the crops, and test the water column for pollutants and security intrusions. It wasn’t unusual for a tender such as ours to be launching and recovering drones and related systems, which made it the perfect cover. Limited to slight modifications for our mission, we had bolted on a few extra comms antennas, mostly laser and other LPI comms, and we sure as hell couldn’t launch any Cormorants or Sea Eagles.

“The forces agreement meant that the only USN and PLAN ships allowed in the SCS were small combatants, while other nations patrolled with larger vessels as part of the enforcement mission. A four-ship flotilla of Lake-class missile corvettes was positioned near us, trying its best to keep a low signature, but sticking out like a sore thumb among commercial traffic. We kept them up to date on our ops, and they were ready in case things got hairy. The USS Wayne P. Hughes was the manned command ship; the remaining three were unmanned versions of the same class.”

The AI shifted is pipe from one side of his mouth to the other. “You were operating in an area that could combust at any time, and you were on an unarmed vessel.”

“And it got messy quickly.”

“One of the purposes of this project is to capture vignettes of important phase changes of the war. And we think your part was a big one, because it was when a new facet of Chinese operations was discovered.” The professor said, tapping his pipe in an ashtray. “I hear it was a close call for you, and I would like to record accurately what happened at that seafarm.”

“Are you interviewing the Skipper of the Hughes?” Fernandez asked.

“CDR Zhu? Of course. One of my personas talked to her last week.”

“I’m sure she chose John Paul Jones as her interviewer.”

“Actually,” the AI said, without looking up from his notes, “she went with Admiral Nelson. It took us a few seconds to render the HMS Victory under full sail, but it was an informative discussion.”

“Good. I bought her beers after she got out of rehab. That woman is a straight-up badass. She lost an arm during that exchange.”

_______________________________________

The OCEANUS feed was looking grim. The Yuzhao had blunted the corvettes’ attacks and was now turning its efforts to neutralizing the flotilla, which was just buying time until the inevitable. The unmanned vessels and Fiberclads used their aggregated swarm to protect the Hughes. One by one the Lakes were being sacrificed as their HPM pulses and CIWS flechette shells were not enough to save them alone.

The smaller Fiberclads died first. Then Tahoe absorbed over a dozen hits before succumbing. Okeechobee was staggered by repeated impacts until a UUV was able to catch up to it. ‘Okee’ broke in half like the Seneca, keel snapped by an underwater explosion. Then the friendly swarm broke away and headed to deflect the attack on the tender.

V-M said what they all realized. “The Hughes is sending the flotilla’s swarm to protect us.”

The friendly UAVs intercepted their Chinese counterparts just as they were reaching the outskirts of the seafarm. The Sea Eagles were able to shoot down drones without sacrificing themselves, while others, such as the Petrels, had to ram the opposition to make an effect. The Polillo 2 was spared.

The Hughes paid the price. Opening broadside to the section of the swarm bearing down on it, it could only rely on its self-defense mounts and was beset by the autonomous adversaries. It fared a little better than the rest of the corvettes, but was still hit numerous times. Dead in the water, the Hughes’ weapons went silent.

“The swarm has been significantly thinned out. It looks like it is pulling back to reconstitute on the Yuzhao,” OS2 breathed out.

“Still trying to get to us over the networks,” CTR2 reported, reading the JANUS feeds. “We don’t have enough resources for our instance of JANUS to out-cycle whatever they are using. It’s only a matter of time before our they are in our network.”

MJOLNIR inbound, OCEANUS reported.

“Never mind.” Cruz whispered.

Fernandez looked at the large display in above terminals. The Yuzhao was 17 miles distant and headed away, wake boiling behind, an anemic swarm of drones in company. Then the enemy ship shook as if a giant finger flicked it. An upper part of the superstructure spiraled away as a gaping hole was punched starboard amidships at the weatherdecks, and the hypersonic projectile exited the port side, spraying a shotgun pattern of debris in the water far beyond.

“Wow. Never seen one of those….” Sara let slip.

“Me neither.” OS2 added. “Higher ups must have really wanted it dead.”

The critically damaged LPD began to slow, fires and smoke pouring from amidships. That hit alone was enough to sink it, even though it was above the waterline. But then the ship went up. A huge fireball began deep in in its hold, followed by a shockwave through the water that could be felt miles away on the Polillo 2. When the blast subsided, what was left of the bow and stern of the broken ship was settling into the water.

V-M began on his multicultural curses again, seemingly happy this time.

“What was that thing carrying?” Cruz asked.

“Probably missile batteries to reinforce an atoll somewhere around here.” Fernandez said. “OS2, what’s the status of the Chinese swarm?”

“OCEANUS shows eleven drones still active of various types.” V-M replied, now done with the swearing. “The blast took out the rest, and there is no local swarm controller now. But we can’t do anything if they are still out there, they’ll self-organize and still be hostile.”

“CTR2, work with US1 to get another pair of drones up. I want JANUS to take control of those drones and splash them.”

“Will do Ma’am.” Cruz replied.

Sara picked up the IC phone again. “Captain, we can go to assist the Hughes now.”

“Looks like it is barely afloat,” Aquino observed. “And what’s left of the Chinese ship is almost under. We’ll see if there are any very lucky Chinese survivors from that blast after we go to the Hughes. Continue acting all civilian and innocent?”

“That’s right.” Fernandez said. “We’re not onboard, remember?” Which was a pity. She wanted to shake the hand of every sailor on that corvette. Instead, her Det will have to hide until they transferred the survivors to a larger Indian or Japanese warship, which was probably now on its way after detecting the clash.

“Let’s hope those Cormorants took all of the Chinese UUVs. By the way, that was one of the craziest f’ing things that I have ever seen,” he added.

“You and me both.” The Det OIC laughed.

_______________________________________

“The covert USN and PLAN vessels rarely came to blows. The engagement between your seafarm tender and the Chinese LPD showed two different means of gray zone warfare with different platforms. One, a concealed warship, the other a fishing vessel with military capabilities.”

“Which, ironically, was a Chinese tactic decades before we did it.” Sara added.

Underlining something in his notes, the AI observed, “Your actions uncovered a PLA operation to establish a bastion in Micronesia.”

She shrugged. “I guess a good cover was a fleet of large vessels supposedly netting tuna.”

“There was an island outpost that was not going to be a threat until the hypersonic batteries arrived. The Det on Polillo 2 revealed that shipment and protected Guam from those missiles. You blocked their next ‘Go’ move.”

Sara paused before saying, “I’ve told very few people over the past twenty years about what happened that day.”

“Well, now you have approval to get it on the record.” The interviewer AI said, making a show of turning over a fresh leaf of paper in his notebook.

“Where shall I start?” CDR Sara Fernandez (ret.) began. “We were only a few days out on an op out of Palawan when my CIC watch messaged me at breakfast…”

Chris O’Connor is a Supply Corps Officer in the U.S. Navy. He has had tours at CNO Strategic Studies Group and CNO Rapid Innovation Cell, and is Vice President of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC). He has written a number of fiction and non-fiction pieces on the future of warfare.

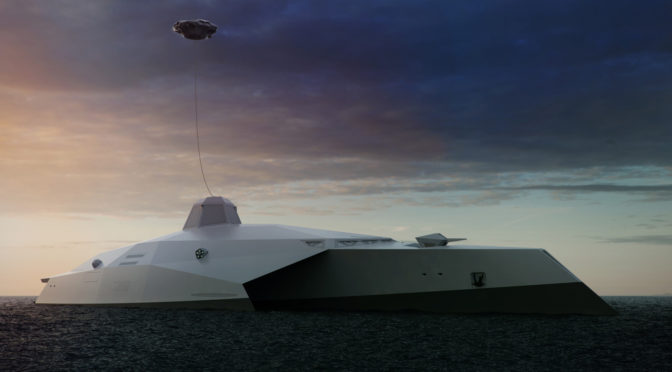

Featured Image: “Grand Imperial Navy” by Rhys Bevan (via Artstation)