By H I Sutton

Helena was studying the screen intently. The blurred pixels of the satellite image clearly showed ships, but whose were they? She scrolled down, heading south towards the artificial reef. Its deep harbor was hacked from coral, thousands of years of life, now dead. There was nothing there. Looking inland there were some jets on the runway. These must be the Chinese Flankers everyone was talking about. Helena was not looking for what everyone else was. She raced back north to her unidentified ships. This was her catch.

There was a clink of porcelain as Aaron placed their refill on the table.

For a moment Helena looked up and surveyed the Starbucks. No one was paying any attention to them.

Aaron settled back down to his own laptop.

They made eye contact. In unison they looked back down at their screens, silently immersing into their hunt to identify the mystery ships. The world was watching the tensions unfold.

The USS Michael Monsoor was known to be in the area. Its harsh futuristic lines harked back to the ironclads of old. None of these unidentified ships were her.

Monsoor’s presence in the South China Sea was well justified, every ship has the freedom to navigate there. But that wasn’t stopping the situation from turning bad, and quickly. China was ratcheting up the rhetoric and mobilizing its navy. Everything looked like this was going to be the trigger for a major confrontation, maybe war.

It seemed ridiculous to the two friends, surely it was only an excuse. If things kicked off, it would be because someone had a bigger motive, not because of the actions of one ship.

The satellite imagery was from earlier that morning. It wasn’t great resolution, each pixel represented about 10 feet of real estate. But it was timely and it was free to access by literally anyone in the world. If a major escalation was about to start, Helena and Aaron would probably know more than the traditional media reporting it. Helena pondered for a moment, maybe she already knew more than some of the captains of the ships? Surely the navies’ intelligence organizations would be closely guarding their intelligence and squirreling away their secrets.

Meanwhile, all one needed was an internet connection to survey the mass of ships gathering near the reef. Some were clearly warships. Helena flicked back to the AIS data which showed ship’ positions in real time based on their automatic radio transmissions. All ships were supposed to do it, except warships. These ones weren’t on the map. They were running dark.

“Bingo” Aaron exclaimed. “Got the Hawkeye data. Someone uploaded it” Aaron shared the link to the data dump.

A message popped up on Helena’s screen. Within a few minutes it had been loaded into a map, showing a mass of dots and lines across the South China Sea. This was a type of satellite which monitors radio transmissions. Zooming in on the area where the unidentified ships had been that morning, Helena saw a trail of yellow lines leading due south. The ships weren’t on AIS, but they were using their radios to communicate with each other, and this was betraying them.

“Do you think we should post something?” Aaron’s tone hinted excitement. Being the first to call a new piece of information would enhance his reputation in the small community of watchers.

“This is bigger than Twitter,” Helena responded. “Do we have anything on Chinese social media yet?”

“A few possibles. There were some photos of one of their carriers, but I think we’ve seen those months ago.” Aaron hadn’t looked up for several minutes. He glanced sideways, wondering whether anyone was listening to their cryptic conversation. “What is Chinese for fishing boat? I think their maritime militia might be a starting point for a search.”

“I know someone who has a bunch of maritime militia-connected accounts. Some of these guys don’t have any discretion about what they post. I will give him a ping.”

“Oh, like this?” Aaron blurted, his excitement was palpable.

Instantly the message window on Helena’s laptop popped up, revealing a photo over the side of a tiny fishing boat. On the horizon were the hazy outline of warships, including a Type-055 Renhai-class cruiser and what looked like frigates. A helicopter was lifting off from the cruiser. These should be their unidentified ships. “Can we verify this? Where it is?” Helena’s initial delight morphed into suspicion. It seemed too good to be true and she was terrified of calling it wrong.

“It’s from Weibo. The original poster says it is from today in the Paracel Islands.” Aaron became defensive. “And here is another. This looks legit to me. Posted 12 minutes ago. It has only been viewed three times.”

In Helena’s mind pieces of the puzzle were coming together.

_______________________________________

8,000 miles away aboard the U.S. Navy destroyer in the South China Sea that same puzzle was still a mountain of fragments. Captain Richards grabbed both rails and propelled himself up the steps two at a time to the bridge, a habit formed over years of service aboard ships, leaving the command center far behind him. Within a couple of paces he was at the line of windows. He lifted his binoculars and surveyed the dozens of small boats on the horizon. It was an old-fashioned tool, anachronistic maybe, but for all the advanced radars, electro-optical sensors, and signals intelligence, he was not seeing the wood for the trees.

His ship was virtually surrounded by fishing vessels. Was it a trap? He had slowed it down to a stop. He was used to having a Chinese warship trail him, even getting in close for a game of cat and mouse. Near collisions were commonplace. But this was different. Where the Chinese expecting him to run over the thick mass of tiny boats in front of him? That would create an international incident. This wasn’t his call, not today. The world would be watching.

For a moment he felt alone, in a sea of jumbled information. It was overwhelming and frankly, the intelligence picture he was being fed wasn’t making sense.

Hundreds of miles above his head a satellite was processing an image. A dozen were passing over the area several times a day. Some were military but most, like this one, were commercial.

_______________________________________

“Satellite refresh in 20 seconds” Aaron couched over his laptop.

They both switched to the satellite providers’ web app. Their access would give them 30 minutes lead over non-premium users.

Helena impatiently pressed refresh on the browser.

After what seemed like an age, the fresh images showed up. Clouds. Lots of clouds.

She zoomed in to her previous coordinates, where the unidentified ships were. More clouds. “You try to the south of the reef. I’ll try the AIS position of that U.S. Navy destroyer. It’s been using an anonymous AIS handle.”

Through a clearing in the cloud she instantly recognized the top-down view of an impressive warship, the Monsoor. It was still in the water. And all around it, just a few hundred yards off every quarter, were tiny blobs. Fishing boats, hundreds of them. Still staring at the screen, Helena suddenly understood. “That ship isn’t going anywhere!”

“What’s up?”

“Monsoor looks stuck, surrounded by the maritime militia. Wow! A billion-dollar warship stopped in its tracks by fishing boats!”

“She is a sitting duck. Welcome to hybrid warfare” Aaron muttered. “I think I’ve found the Chinese cruiser. She is still heading due south, away from the action. The AIS is all messed up now, I think the Chinese are jamming it. Like they did in Shanghai that time.”

Aaron’s coffee was getting cold. It was still morning where they were, but the light would be fading in the South China Sea.

“If the Chinese launch a missile, and nobody sees it, does it make a sound?”

“Oh, you think it is a trap?”

“The fishermen will see it, front row seats.”

_______________________________________

Captain Huang looked out over the bow of his cruiser. The Type-055 was the pride of the People’s Liberation Army Navy. The faceted side of the main cannon’s casing caught the evening light. Between the captain and the cannon was a massive farm of missile tubes. Only the top of each tube was visible, marked by a square outer door. Beneath each gray square was a missile. He was so used to the view that he overlooked them, not giving any thoughts to what was inside.

The important payload, the new missile, was in a special launch container further aft. It was too big for the regular missile tubes, so some had been removed to make space for the wider and taller silos. It was a massive ballistic missile like the ones fired by submarines. But there was an important difference. Instead of a nuclear warhead, each missile had a small glider which could be steered onto its target at hypersonic speeds. One hit might be enough to sink an aircraft carrier. Or a destroyer.

“Are the new missiles ready?” Zhou asked as he stepped up beside the captain.

Senior Captain Zhou was the political commissar and the most senior officer aboard the ship. It was normal for PLAN warships to have a commissar on board, jointly commanding the vessel. On this ship he was the more senior of the two men, not that it should have mattered. The military commanders were anyway unfailing loyal to the Chinese Communist Party.

Technically Zhou and Huang were supposed to agree on each course of action but on missions like this, missions of national importance, everyone knew where the real power was.

“Your secret weapon is as ready as it needs to be at this moment.” Huang’s response had equal hints of mockery and resentment.

“There is no need for childish remarks, Captain. We are about to make history.”

Huang wasn’t listening. His mind was on the thousand tiny tasks which had to be done aboard the ship to launch the six missiles.

It was a completely new system and had not been tested from the cruiser before. Normally a weapon would have been tested many times before entering service, but this had been rushed. And hushed. And for the missile to be deniable it was important that, in the eyes of the world, it did not exist. No one should know that the cruiser had been fitted with the new weapon.

“Captain Huang! Are you with us? Captain!” Zhou was agitated. He had been talking and was sure that Huang was ignoring him. He was right.

“Yes,” the captain was momentarily back on the bridge. He deliberately didn’t acknowledge his senior’s rank. This was his ship, or at least it should be. “There are many things to be prepared,” he continued, expecting to be left alone.

“You cannot hide your mind in the details. We are but a small piece of a larger picture. A pictured viewed clearest from Beijing.”

Zhou paused, as even he knew the lecture was pointless. Huang, professional to the end, would do his job when the time came. He turned on his heels, but his rubber soles did not make any sound. Marching off, he feigned more important things to be getting on with.

Minutes later, 16 of the crew ran through the narrow passage that led along the side of the ship, up through a hatch and onto the aft deck where the second farm of vertical missile silos was. They quickly ran to their designated places around the blue tarpaulin which covered the new launch tubes.

Six of the silos where larger in diameter. They stood proud of the rest, about three feet higher. In all the six new missiles took up the space used by sixteen of the regular tubes, but it would be worth it.

Soon the tarpaulin was removed. The hatches of the special missile tubes were exposed for the first time since leaving the shed where she was built.

Captain Huang brought his binoculars up to his eyes and looked out of his bridge. Like Richards aboard the Monsoor, he took comfort in the simplicity of the age-old practice. Soon Huang’s ship would be far enough away to launch the attack.

_______________________________________

“Lunchtime?” Aaron said finally. He set his laptop down to one side on the bench, keeping one eye on the open screen. He was waiting for the next nugget of open source intelligence about the situation in the South China Sea.

Helena nodded, not looking up. She was frozen, looking at the same image for minutes now.

On her screen was the satellite image of the Monsoor surround by tiny fishing boats. Was this it? The end of the U.S. Navy’s freedom of navigation voyage? The end of the world’s freedom to sail in the South China Sea? She couldn’t help but think that there was something bigger going on.

They sat at the next table, with a view out into the street. It was dark inside and gray outside.

Helena was stuck for a moment, gazing blindly at the rain splattering on the empty sidewalk outside. Days weren’t usually like this.

Their laptops and spent coffee cups were still stating claim to the other table; this was their corner of the coffee shop.

A young barista came over and started clearing their old plates.

They both eyed him suspiciously as he scooped up the crumbs around their machines. As is the custom, nothing was said.

As he scurried off they picked up their sandwiches and took a few bites. They realized that they were starving.

“So?” Helena finally broke the silence.

Aaron bit his lip, holding in the excitement. His eyes betrayed him.

“Well what do we have?” Helena continued. It was a rhetorical question, they both knew she was the leader. “There is a U.S. Navy warship which is supposed to be conducting a Freedom of Navigation passage near the Chinese occupied reefs in the South China Sea.”

She held her left hand up and started counting with her fingers. That was one. “It’s not exactly routine, given all the rhetoric recently, but it would be a non-story if both sides let it to be.”

“But Beijing has chosen this moment as the watershed” Aaron added. “No more U.S. Navy in the South China Sea, it is their patch.” He was her perfect foil.

“Yes, this cannot end well. We know that the U.S. Navy won’t back down. Beijing knows that, everyone knows that. So they must want the Navy to react. They want an incident.”

She pulled down on the middle finger with her right hand: two. “It is stopped by a massive fleet of fishing vessels. These must be Chinese, and they must be part of the maritime militia.”

“A swarm.”

“Yes. They are acting as one unit. It is deliberate and there is no way they are fishing. So Beijing must be controlling them.” She paused, then grabbed her ring finger. There was no ring on it. “Three, there is a gaggle of Chinese warships, including a Type-055 Renhai-class cruiser, about 200 nautical miles south.”

“The bait maybe? Or they are running away?”

“No, I’m not buying that. Maybe they are holding back so that the confrontation appears to be between the U.S. Navy and civilian vessels? That would look better for them on the TV screens.”

“Or there is a military reason. Like the nuclear option?”

“That would be crazy. There is no way that the Chinese would use nuclear weapons that close to home. That close to their own people.”

Aaron raised an eyebrow. He wasn’t so sure. But he knew anyway that a nuclear attack did not seem likely. Within a fraction of a second his mind had raced through logics and reasonings. A tactical nuclear attack on the U.S. Navy just seemed like a really dumb way to start World War Three.

But maybe there was another weapon that the Chinese had in mind? Something which needed their warships to be hundreds of miles away. “If the Chinese attack the USS Michael Monsoor, that’s war,” he said. “This doesn’t make sense. Any attack would be tied back to them in a second. So I think their game is provoking us, they want an over-reaction.”

“Unless” Helena challenged, “they have a way of attacking which they can deny. Like the North Koreans did with that South Korean ship, the Cheonan.”

“China doesn’t have a deniable weapon. Any attack would be all over the internet in seconds. Every boat in that fishing fleet seems to be on the internet. Have you seen the Fox article, even they are getting their videos from Weibo.”

“Maybe.” Helena conceded. “But none of the media outlets have that Chinese cruiser on their feeds. Maybe we should break the story after all?”

“Let’s let it develop a bit more.” It was Aaron’s turn to be the voice of caution. “If we are wrong about the cruiser then we could be adding fuel to the fire. This could have real world consequences.”

He sat back, mopping his mouth with a napkin. He checked his phone momentarily before shifting back along the bench to his laptop. He was addicted to both devices.

_______________________________________

Aboard the American destroyer Captain Richards was still on the bridge. His XO had joined him.

“Shall we launch the interceptor boats now that it is dark sir? Maybe make a hole in this noose?” she asked.

“No thank you. The last thing we want is any bloodshed. Or worse, prisoners.” He paused. “Send up a helicopter, see if its downwash can clear a path.”

“Yes sir.” The XO acknowledged the order. She turned to their staff who were loitering in the shadows at the back of the bridge.

_______________________________________

500 nautical miles to the south the Chinese cruiser was finally ready to launch. Both senior officers were in the command center. They had seemingly repaired their earlier differences.

As the large digital clock on the wall turned to 18:30 hours the commissar triumphantly shouted “Fire!”

The room was full of attentive junior officers and sailors. No one did anything, instead keeping one eye on Captain Huang. He was the boss of the ship, at least in fighting terms. And anyway, Zhou had no idea which sailor he needed to order, or what exactly they were supposed to do.

“There must be no warning, and no survivors aboard the American warship” Captain Huang said after a deliberate pause. There was no emotion. “We have to hope that they do not have any means to detect our military action.”

He breathed as if preparing to deliver an important speech. But there was nothing he could say that could starve off fate.

“Special vertical tubes missile batteries make ready, low flight trajectory, pre-designated target, United States Navy destroyer 112, target coordinate at,” he looked up at a display, “12.1 Port.”

He watched as three sailors in neatly pressed blue camouflage uniforms ran through their drills. They vocalized each step, yelling into the silent room. The excitement blotted out the background noises.

Within moments Huang had received the confirmation that the steps had been taken. “War alert! Launch four special vertical tubes, sequence 1, 3, 2, 4, at five second intervals,” he said firmly, adding “No delay.”

“Only four?” Zhou challenged. He had understood that all six were to be used, that would be the normal principle of a saturation attack.

“Four is enough, it is only a destroyer.” His duty was to his orders from the Party, he had done his duty. “And we never know when we might need the others.”

Moments later the bright flare of the missiles being launched erupted from the stern of the ship. Soon all four of the giant missiles were airborne, charging skyward. Their smoke plumes caught the very last traces of the evening sun.

_______________________________________

Aboard one of the fishing vessels two men were training their night vision camera on a large warship. It was now not more than a couple of hundred yards away.

Suddenly the night sky became daylight as explosions erupted above them. They instinctively ducked back into the open topped boat. Looking up, terrified, they saw a shower of sparkling confetti slowly floating down. More explosions were happening higher up.

Although they did not recognize it, they were underneath a cloud of metal chaff and flares, designed to mislead the incoming missiles. The USS Michael Monsoor’s defenses were going into overdrive.

Above the pop of the firework-like pyrotechnics the fishing boat crew could hear the alarms on the warship. Suddenly rockets streaked up into the sky, as if signaling the imminent climax of a fireworks display. It was the ESSM air defense missile system. It was all the ship had.

The alerts came too late for the Monsoor.

The last-ditch defense was in vain. The incoming rounds were travelling at hypersonic speeds and maneuvering just enough to make targeting them extremely difficult. The destroyer wasn’t equipped with anything designed to take them on. Three of the Chinese missiles scored direct hits, breaking the spine of the ship.

The two fishermen eventually regained their composure. Without saying a word they began filming again, just as they had been instructed.

The mayday transmission was garbled, jammed by equipment aboard the supposed fishing boats.

These small boats then began hunting for survivors, rinsing the decks of the rapidly sinking warship with gunfire. The crackle of sporadic assault rifle fire echoed in the darkness. There were to be no survivors.

_______________________________________

Helena’s twitter feed suddenly sprung into action.

Alerts and messages retweeted a statement from the U.S. Navy’s official twitter accounts. An unnamed U.S. warship was involved in a vague incident in the South China Sea.

They knew it was the Monsoor.

But the official statement was being drowned out by videos of the burning warship. There was no doubt that it was sinking. The videos were already going viral, being shared millions of times.

Even the TV in the coffee shop was showing the videos non-stop. The ticker headline read “U.S. Navy ship damaged in tragic accident.” Random commentators shared their wild speculation, and TV anchors pretended to know about warships.

“This is insane.” Aaron was dismayed. For the first time it felt real. “The Chinese are saying that the ship exploded without warning. People are saying that the U.S. Navy was attempting to make an attack or something. Or that it was an engine malfunction. No way to all of that…”

“Luckily all those Chinese fishing boats were there to pick up survivors…” Helena said numbly.

They had both noticed that none of the videos had sound, and that there was no word or sign of survivors.

“The Chinese are controlling the narrative. Information warfare 101,” Aaron concluded.

“Quick, what’s happened to that Chinese cruiser? You check the social media, I’ll see what the latest satellite imagery looks like”

They both dived back into the internet, the hunt was on.

_______________________________________

“Hi Helena, Aaron. So I guess you want to talk about the accident in China’s waters? I just heard that Beijing is declaring an emergency and closing the seas around it. They are doing a press conference in 20 minutes, which my network is broadcasting live. Busy news day!” Brandon was sitting in front of a bookshelf. Disorganized blocks of books, some piled the wrong way, were only to impress. He had moved the old bookshelf behind his desk to make him seem more credible in Zoom meetings like this.

Helena tried to read the titles of the books. There were none that she recognized, nothing on naval history or warship recognition.

“It’s not in Chinese waters, it’s in international waters.”

“Their exclusive economic zone I meant,” Brandon cut her off. “It is their backyard, right. What was a Navy ship even doing there? And those poor fishermen, we are expecting a massive collateral body count at the news conference…”

“It doesn’t look like an accident,” Helena interjected, trying to wrestle control of the conversation. “The Monsoor was set up, and it is obvious that the Chinese did it.”

“Monsoor was that U.S. battleship, right? Right. All the open source intelligence supports what the Chinese are saying Helena. You’ve seen the videos.”

“Those aren’t OSINT, Brandon, that’s information warfare. It is the Chinese narrative, they want us to take them at face value. We have to look at the bigger picture.” His tone was already annoying her, but she was trying not to show it. She hated that he didn’t know the difference between a destroyer and a battleship. Was he doing it on purpose to bug her? Probably not, his reports were full of errors.

“Listen, the news cycle is dominated by that video of the burning battleship. And now this news conference. Unless you have something massive it will have to wait. Maybe Tuesday or Wednesday cycle?” He was trying to sound like he was in a hurry, it was a power play.

“Isn’t there a version of events from the Pentagon or White House?”

“Nothing worth reporting. You know how it is, by the time they pull a proper presser people will have moved on.”

Helena took a deep breath. She had never fully trusted Brandon, but this was their best chance.

“We do have something massive, that’s why Aaron messaged you. There was a squadron of Chinese warships which were acting suspicious. We need your help.”

“If I help will I get the exclusive?” He was shortcutting straight to the deal.

“Ok.”

“What help do you need?”

_______________________________________

Aaron studied the image. It was incredibly rare to get high resolution images of ships at sea. The satellite companies normally turned their cameras off over open water to save energy and bandwidth. But with Brandon bankrolling it they had been able to task one to take a strip of the South China Sea. They had to miss the site of the USS Michael Monsoor sinking but they had caught the Chinese Type-055 cruiser.

“You guessed the coordinates of the Chinese warship perfectly. Impressive. And you were right, it’s definitely a Type-055,” his voice suddenly sounded unsure. “Something looks odd, though”

Helena quickly brought back the earlier images of the ship. Despite their lower resolution the tarpaulin over the second set of missile cells stood out. A blue blob a couple of pixels wide.

“There was a cover over the aft vertical launch system. That’s gone now,” she replied. “And the hatches seem discolored, maybe scorch damage?”

“And those VLS doors are bigger, aren’t they? Look at them compared to the ones up front.”

“Get your friend Brandon on Zoom again. Tell him the Chinese news conference is already old news.”

“Let’s wait,” His voice began trembling now. His mind pictured the burning ship, and the Chinese cruiser steaming through a choppy sea. He imagined the captain aboard the Chinese warship and wondered what he was thinking. He had no idea. He had never thought about the human element in his work before. Targets were just pixels on a screen. Hundreds of people, crews aboard the ships, were just datapoints. He was in over his head. “This is way bigger than anything we’ve found before. What if we make the incident worse with this? What if we are wrong?”

She glared at him over the top of their laptop screens. Beads of sweat caught the light in the furrows of his brow.

“We have to do the right thing.”

_______________________________________

The banner at the bottom of the screen read “Breaking News.” It had lost its meaning. Brandon sat squarely facing the viewer, his manicured hands grasping a piece of paper. Like the banner it was redundant. Looking straight ahead, he read the autocue.

“This just in. The Navy ship, USS Michael Monsoor was sunk this morning. Contrary to what we are hearing out of Beijing, Chinese warships may have been involved in the incident.” His caveats and ambiguous words were carefully chosen to be ignored by the viewers. “We have exclusive information that a squad of combat ships, centered on the Chinese Navy Type-055 battleship, was shadowing the U.S. sailors.”

His constant misidentifications were grating Helena. She watched intently, anticipating what was coming next.

“Exclusive satellite images suggest that the Chinese warship fired a missile…”

The satellite imagery she had gathered, complete with her labels, flashed up on the screen.

Helena felt a moment of jubilation. Complete satisfaction.

The broadcast abruptly cut to another presenter. A lady on the ground in Taiwan.

“U.S. forces are on the move here in Taiwan. A helicopter, said to have escaped from the USS Michael Monsoor moments before it exploded, landed about two hours ago. We don’t know what these survivors said to their leaders, but we can see the results. We have counted three U.S. Air Force transport planes in the past hour.”

A fighter jet roared overhead, drowning out her broadcast.

Helena looked away. She slumped back on the sofa, tasting the silence in the room. Her dog looked at her, needing reassurance. Was it all going to be alright?

H I Sutton is a writer, illustrator and analyst who specializes in submarines and sub-surface systems. His work can be found at his website Covert Shores.

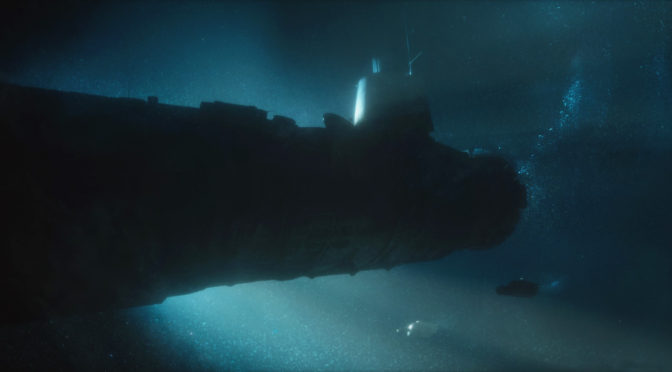

Featured Image: “A Quick Turnaround” by Anakin Ryan (via Artstation)