This piece was originally published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Anthony H. Cordesman

There should be a clear difference between efforts to provide unclassified documents that explain and justify U.S. military forces and issuing official reports that are little more than public relations exercises. The U.S. faces major security challenges and the annual cost of U.S. defense is over $760 billion, even if one ignores the cost of nuclear weapons, the Veterans Administration, related activities of the State Department and other agencies, and substantial additional intelligence activity.

The effort to shape U.S. forces and strategy must deal with very real threats. They include a Russia that has invaded the Ukraine, a China that is actively seeking to challenge the U.S. in military and economic power, and regional threats like Iran and North Korea. The U.S. must cope with emerging and disruptive technologies that constantly alter the nature of military forces in unexpected ways, support America’s strategic partners on a global level, and deal with near collapse of many arms control efforts and major increases in Russian and Chinese nuclear and long-range strike programs.

Far too often, however, the Department of Defense issues documents that are little more than sales pitches – filled with slogans, and that are an awkward cross between a shipping list that borders on being a child’s letter to Santa Claus and a used car commercial.

The CNO’s Navigation Plan for 2022 is a case in point. In fairness, it does highlight a long list of important points about the threat, and the need to reshape U.S. naval forces, but it comes far too close to burying them in overall and hype. It fails to meaningfully address and justify the cost of the U.S. Navy, to provide any clear picture of the threat, to address the need to cooperate with key U.S. allies, and to provide a clear program for shaping the Navy’s future.

It is scarcely unique in failing to provide a clear and meaningful plan. The defense budget requests talk about being strategic documents, but almost all of their contents are shopping lists for individual military services. U.S. strategy documents have become little more than long lists of broad goals and wish lists with no actual plan, program, or budget.

The U.S. no longer issues a meaningful Five-Year Defense Plan (FDYP) with force levels and costs, and no real “net assessments” have been issued at the unclassified level. Aside from an annual report on Chinese Military Power, there are no documents that summarizes the threat, and reports on Russian and Iranian military power have not been updated for years. The U.S. State Department has finally killed a public report on World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers that once served as a reference for much of the world’s media and military analysis – one that it had already rendered confusing and difficult to use.

Still, the Navigation Plan for 2022 represents the kind of empty hard sell that no one needs and highlights the contrast between U.S. defense papers and the far more detailed and useful work done by some other countries – with Japan’s Defense of Japan 2022 being a prime example. The relentless hard sell is bad enough, and so is the tendency to deal with every possible issue by setting a goal that is little more than a slogan with no clear plan or priority for tangible action.

That said, the substantive problems in the Navigation Plan for 2022 go far deeper:

1. Strategy, Predictability and “the Five-Year Rule”

The Navigation Plan talks about planning for 2045 as if the needs for U.S. forces this far in the future were predictable. Like the Quadrennial Defense Reviews (QDRs) issues in the past, it tries to look too far into the future in grand strategic terms without addressing even near-term future and force costs in specific terms. It does so without recognizing the need to regularly update and revise a fully defined strategy for the coming year and a future period that was reasonably predictable.

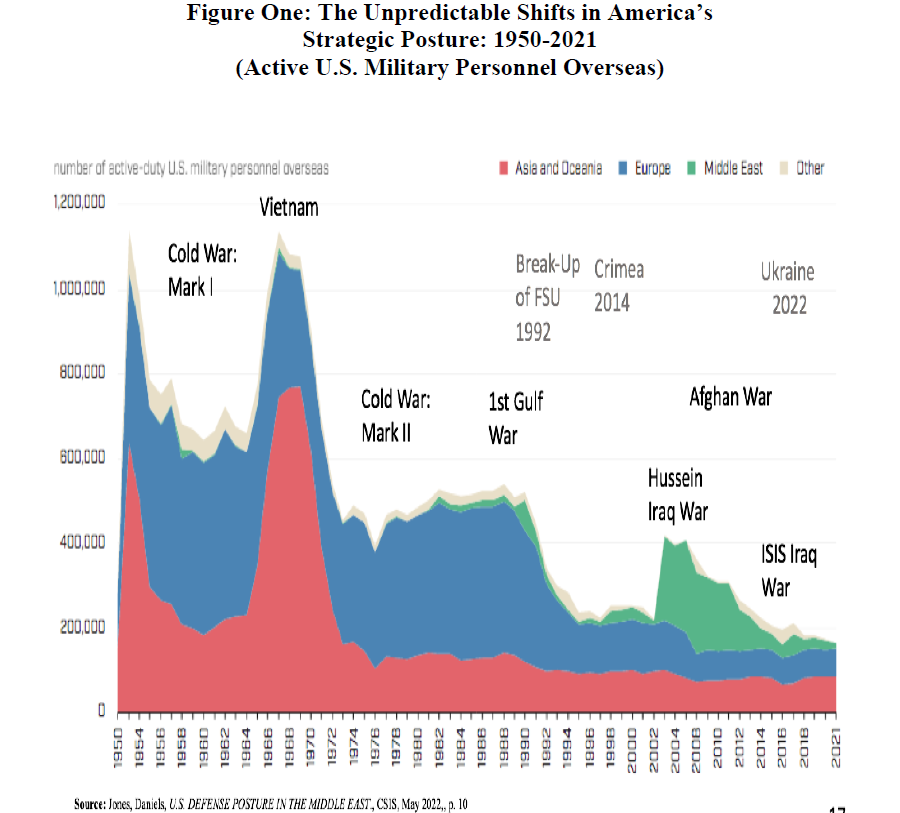

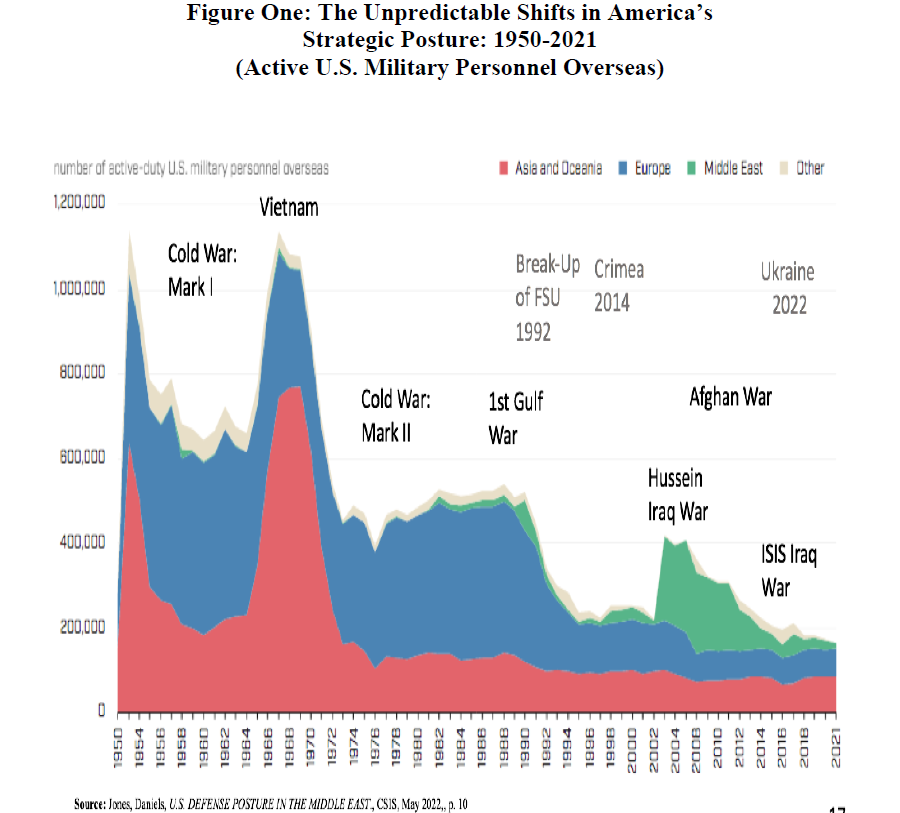

In the real world, 2045 is a long, long way in the future, given global instability and the uncertain priorities for U.S. forces. In practice, we haven’t been able to do a particularly good job of throwing a FYDP together since the end of the Cold War. Figure One shows the turning points in U.S. force levels between 1950 and 2021. It is clear from this histogram that our history of military commitments since 1945 has had so many sudden shifts that it proves that it is barely possible to set goals for planning a workable strategy even five years into the future.

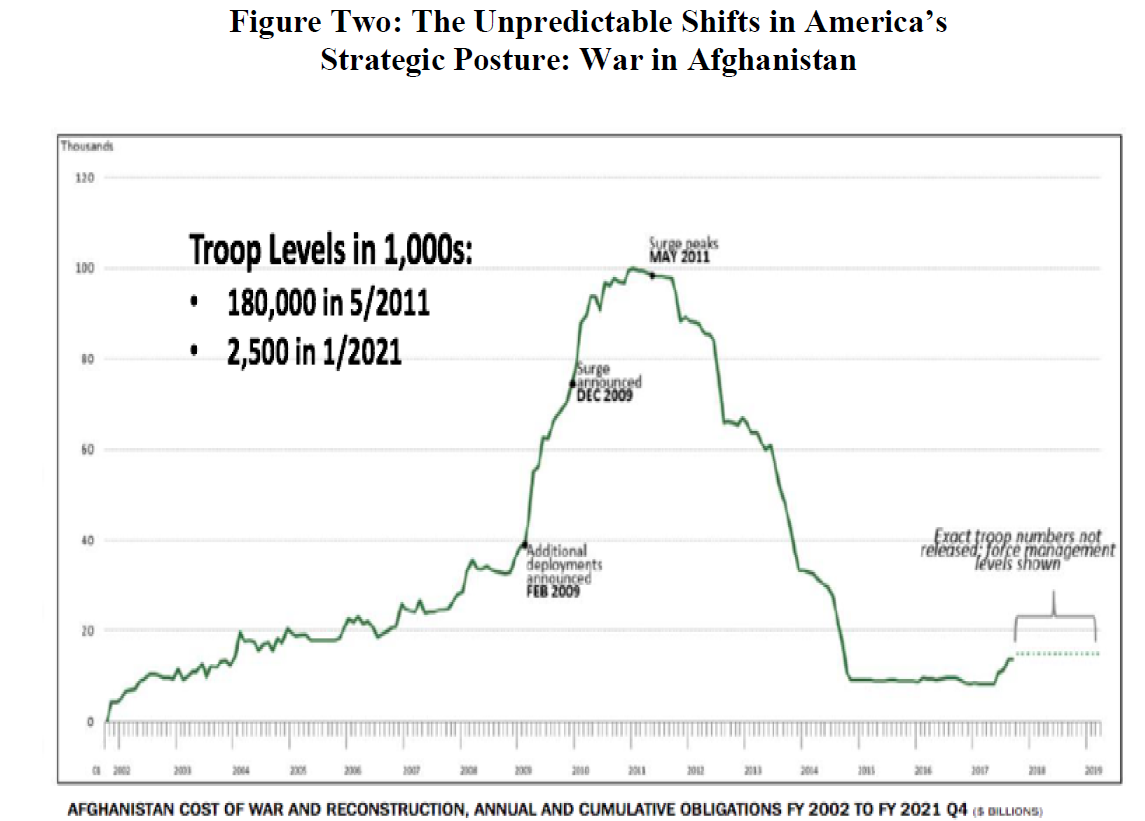

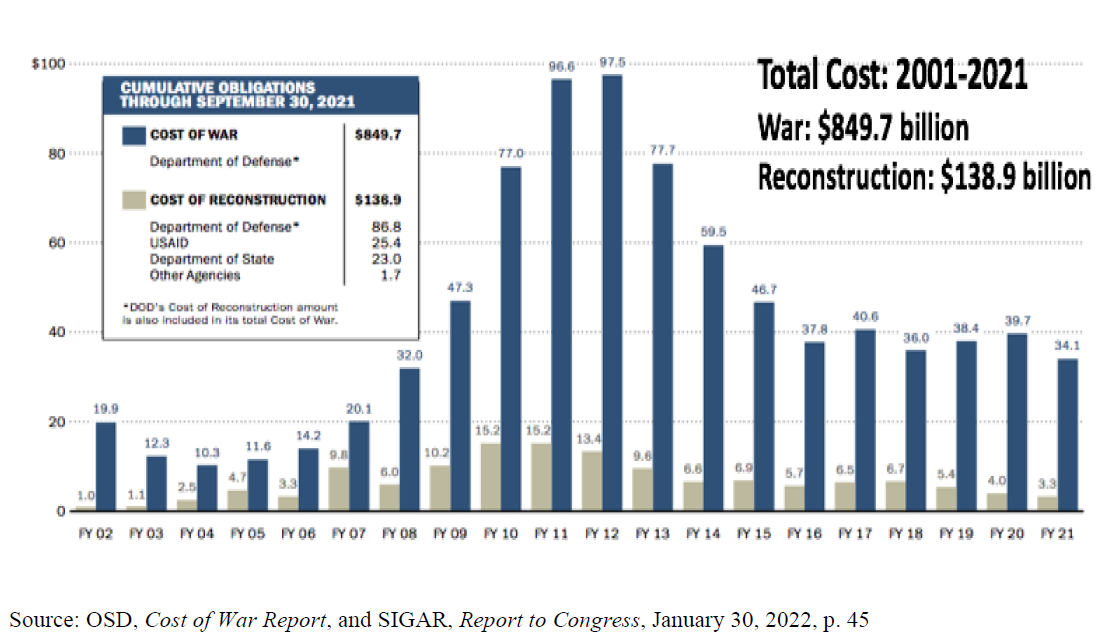

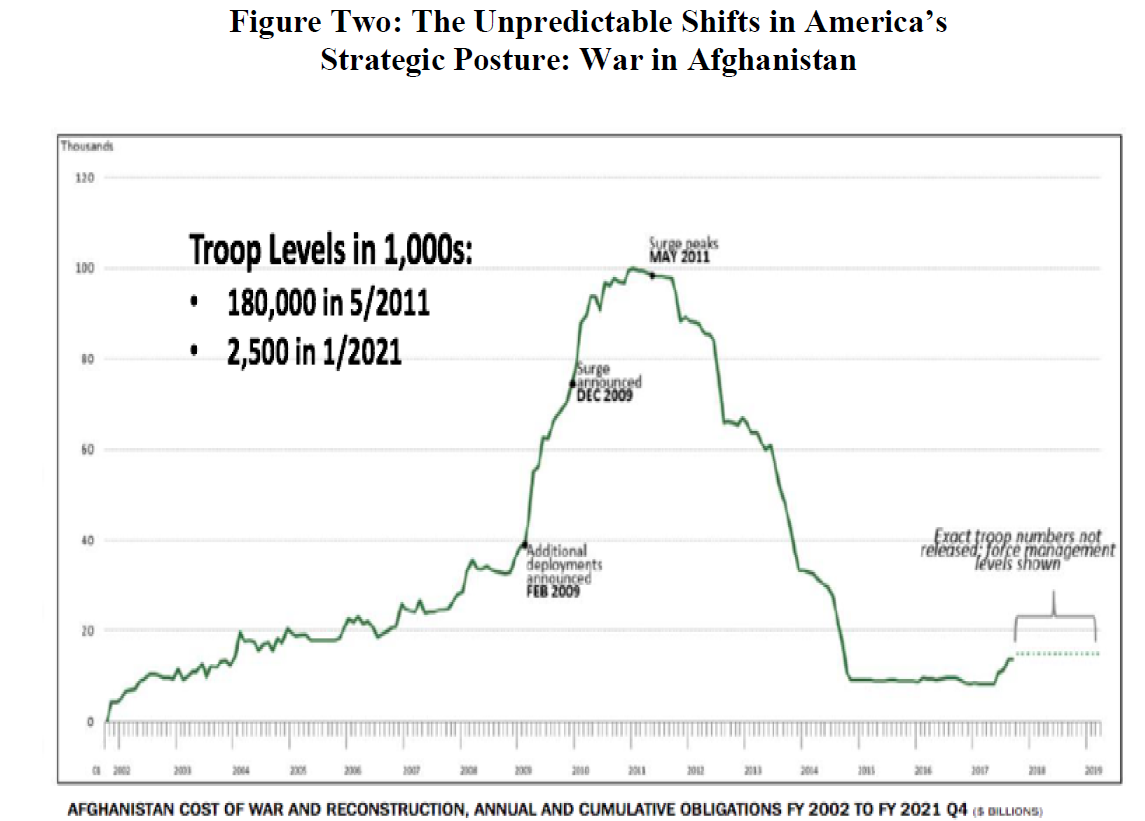

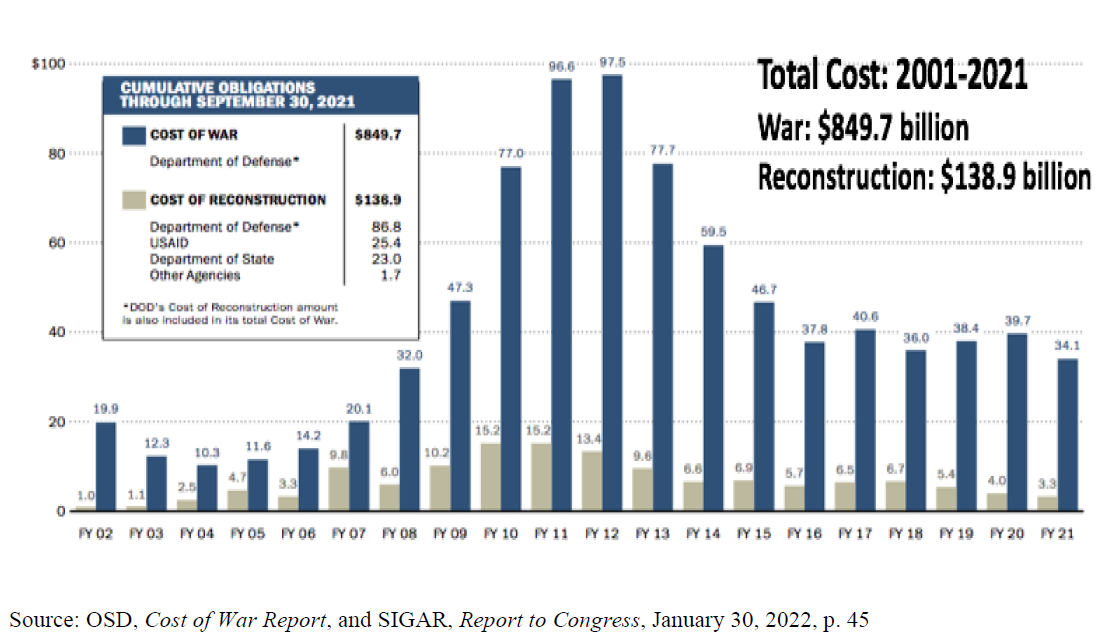

Figure One would also portray far more key points of uncertainty if it included a histogram of nuclear forces levels, strategic priorities, and the role of arms control. The same would be true if it included a histogram of the major shifts in China’s posture and goals and military spending, if it included a chart of the shifting impact of the past versions of new and disruptive technologies. And, if one needs a more tangible example of a massive sudden surge in military spending that had only minimal ties to sea power, Figure Two shows the pattern of unpredictable strategic commitments and military defense spending for the war in Afghanistan.

In practice, even efforts to draft a realistic Five-Year Defense Plan means constantly adjusting the past year’s FYDP on a rolling annual basis and taking account of civil needs and the steady growth of civil entitlement spending.

2. Assumptions about Future Spending and Resources

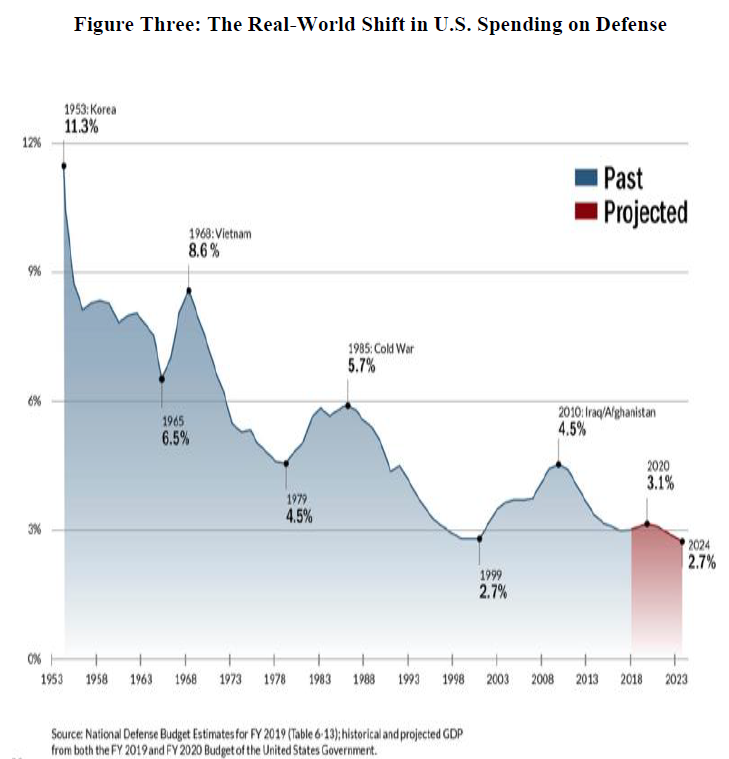

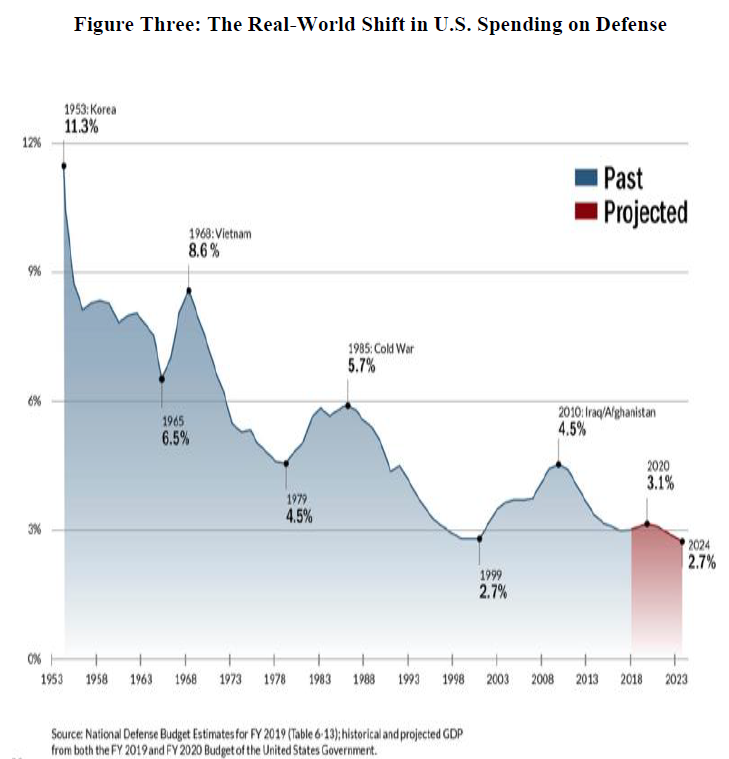

No one can credibly define a strategy without a force plan and clear assumptions about resources. Figure Three highlights the past levels of sudden change and uncertainty in U.S. forces and budgets and looks at some key budget trends. It warns that U.S. spending levels have steadily dropped as a percent of GDP since the height of the Korean War, and that a case for major increases in the quality of U.S. forces requires detailed justification.

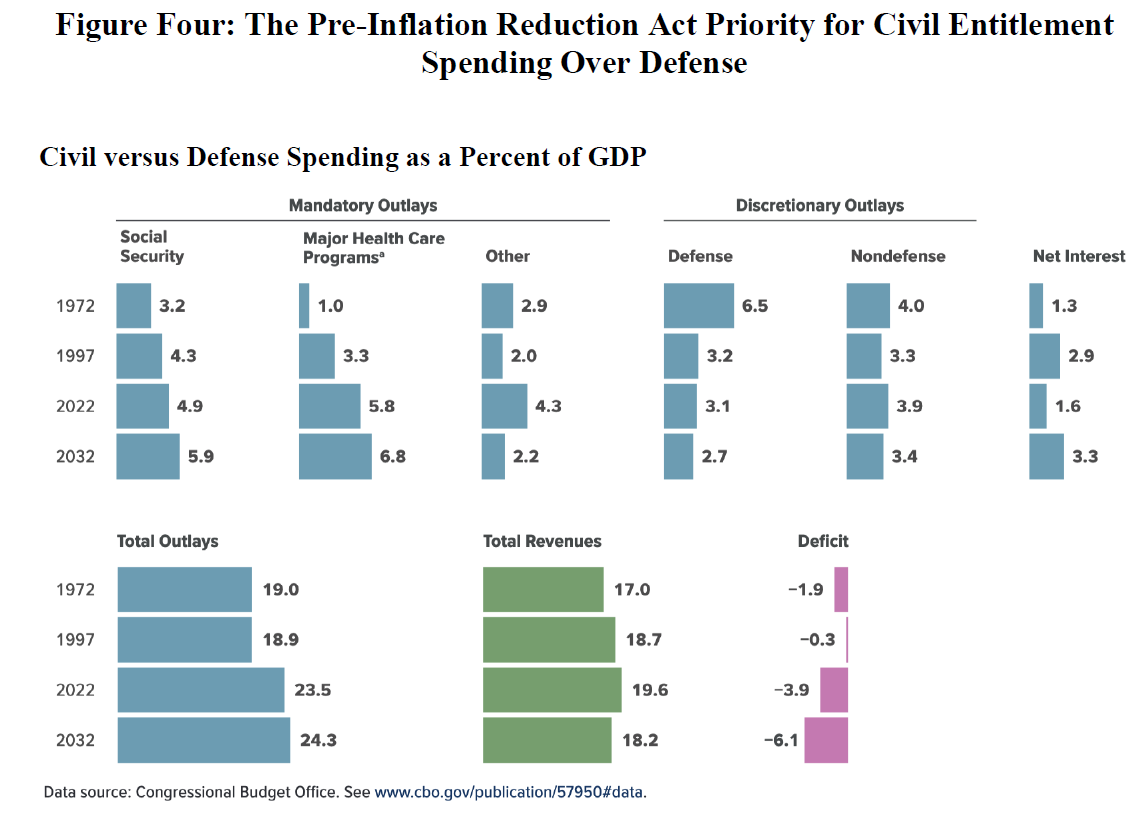

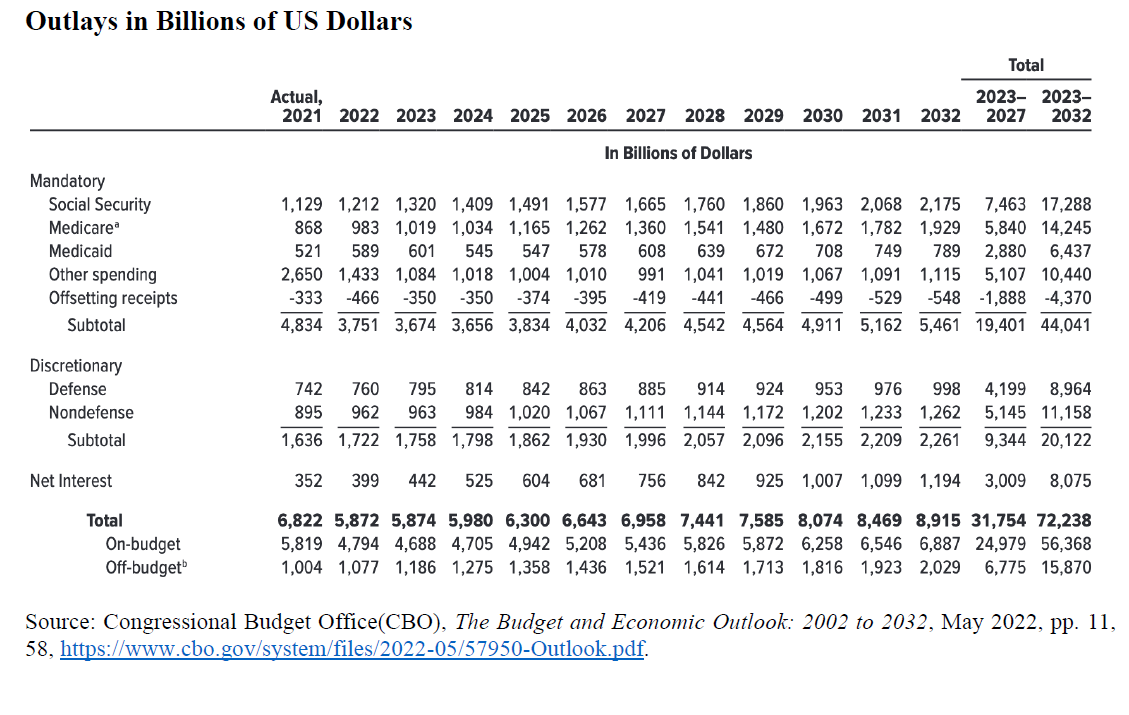

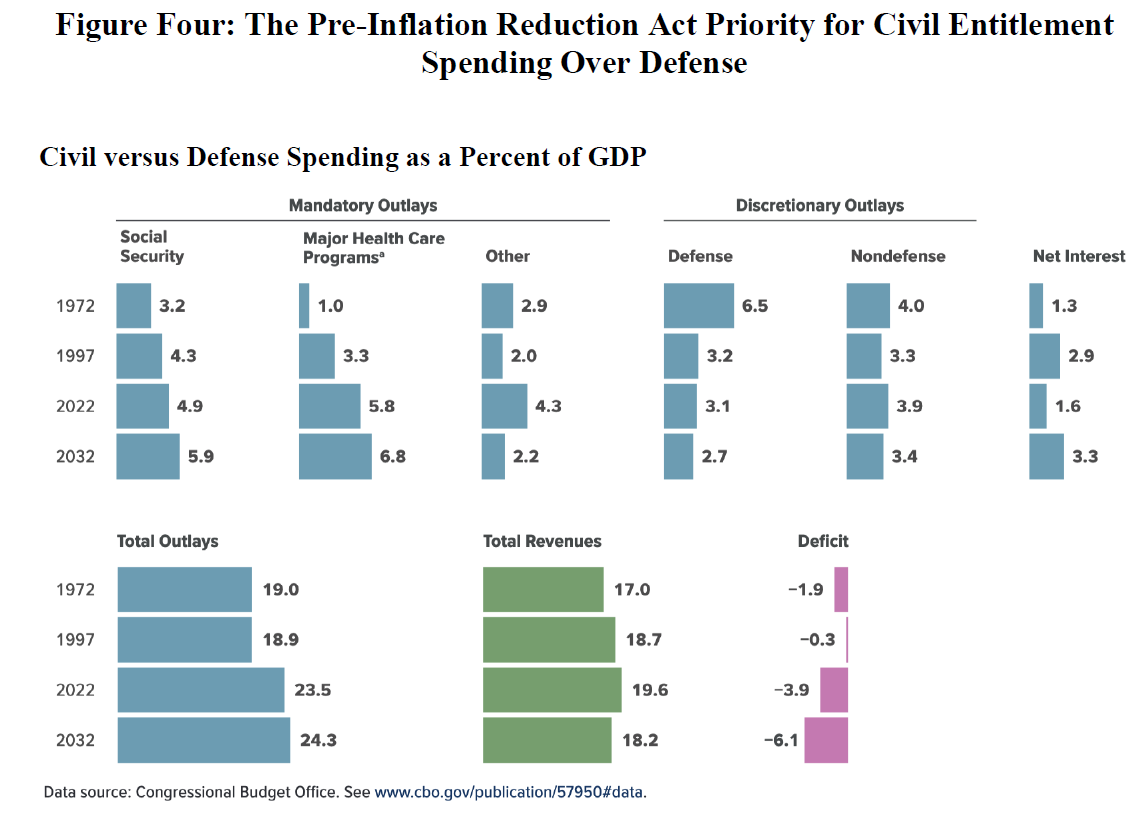

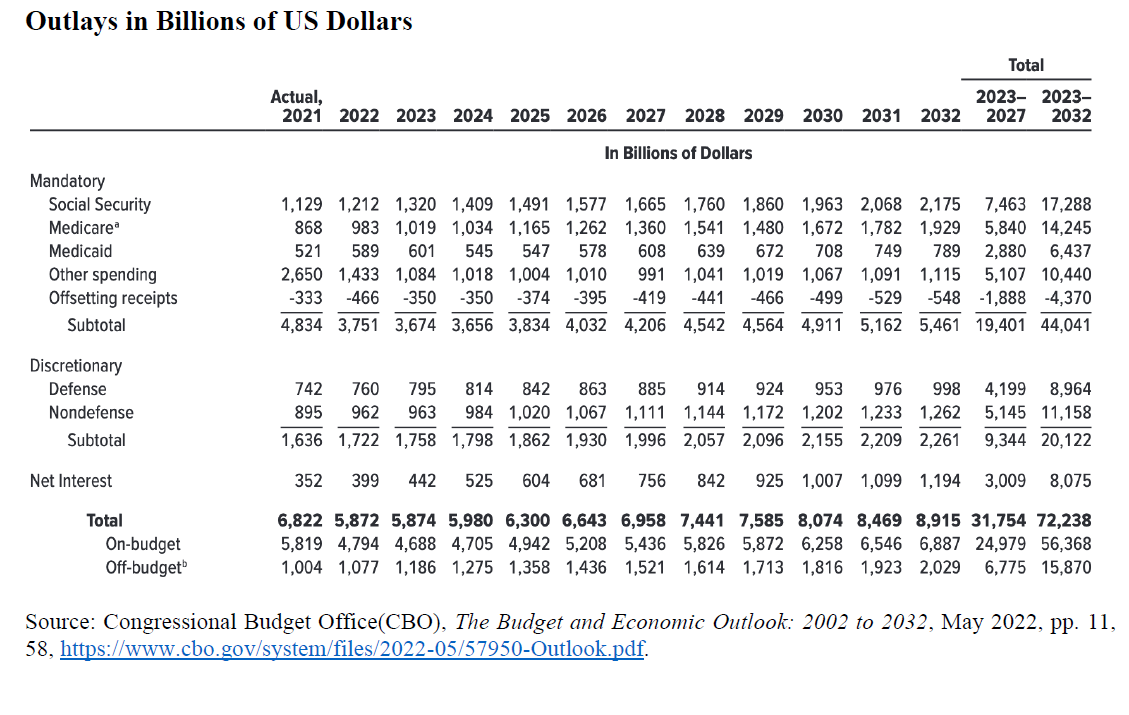

Figure Four warns that current budget projections call for just the opposite trend, and it does not take account of the major new levels of civil spending that have just been enacted by the U.S. Congress. The assumptions the Congressional Budget Office is making about cuts in the future U.S. defense effort call for cuts in defense spending from 3.6% of GDP in 1995, and 3.2% in 2022 to only 2.2% in 2030. In contrast, they call for major increases in Social Security and Major Health Care Programs, and Net Interest.

Long before the signing of the Inflation Reduction Act, the Congressional Budget Office projected major cuts in the level of national defense efforts in order to meet civil needs. It sent a clear warning about the uncertain relevance of any U.S. defense strategy based on broad, undefined goals and priorities, and that focused on desired U.S. defense and forces without any references to budget needs and constraints.

It highlights the fact that there was a reason for including the Future Year Defense Plan (FYDP) in past statements by the Secretary of Defense and in the defense budget request – even if recent projections have rolled the FDYP forward without any clear ties to future force levels and strategy.

However, the Navigation Plan calls for more with almost no detail or justification. It states that,

“To maintain our advantage at sea, America needs a larger and more capable Navy. Faced with peer competitors and emerging disruptive technologies, the Navy needs to become more agile in developing and delivering our future force. Above all, our naval forces must be combat credible — measured by our ability to deliver lethal effects in contested and persistently surveilled battlespaces.” (p. 7)

This need for more naval spending may well be true, but the same may be true of the other services and the Congress has already made major increases in long term federal spending. A Navigation Plan with no funding plan at best follows the Oliver Twist approach to asking for porridge. It simply asks for more.

3. Buzzwords and Generic Goals are not a Strategy

The sections in the Navigation Plan that cover “Force Design Imperatives” and “Force Design 2045” dodge around these issues by citing six “imperatives” that are so broad that they call for advances in every area that is the focus of current force plans.

The Plan lists a “Force Design 2045” and a “need for a more capable, larger Navy” (pp 9-10) which do not seem to track with the options in U.S. shipbuilding plans reported by the Congressional Research Service. The plan refers to rapidly evolving competitors, but then sets the following broad goals for 2040 – some two decades in the rapidly evolving future: “In the 2040s and beyond, we envision this hybrid fleet to require more than 350 manned ships, about 150 large, unmanned surface and subsurface platforms, and approximately 3,000 aircraft.”

It then goes on to list undefined “capacity goals” for ships by type or class but does so without advancing specific goals for given time periods, does not clearly relate them to the previous force goals for manned and unmanned ships, and justifies each set of such goals largely in terms of strategic buzzwords.

Resources are only addressed to the extent that the section on “Navigation Plan Priorities” states that,

“To simultaneously modernize and grow the capacity of our fleet, the Navy will require 3- 5% sustained budget growth above actual inflation. Short of that, we will prioritize modernization over preserving force structure. This will decrease the size of the fleet until we can deploy smaller, more cost-effective, and more autonomous force packages at scale.”

The following section on the Navigation Plan Implementation Framework (NIF) then sets 18 generic priority areas which are only specific in terms of recent and short-term actions, and whose main message seems to be that the Navy’s planning effort has been reorganized, but there as yet is no real strategy or plan.

It might well make sense to try to look as far ahead as 2045 if this was the final section of a strategy based on an analysis of short-, medium-, and long-term issues, priorities, and diminishing levels of confidence – focusing on specifics in the near term and trying to identify key issues for the future. Right now, however, we can’t even assess how a key threat like Russia will behave even three years into the future or predict our strategic path with China.

4. Integrated Strategies, AI, Cyber, Space, and JADO

The document talks about integrated strategies, and all domain operations and warfare. These presumably include key space, AI, and programs, and “integrated” implies an effort to integrate the Navy’s efforts with those of the other services, the needs of the major national and regional commands, and the forces of our strategic partners. However, the Navigation Plan does not address any of the practical priorities and needs involved. It does not have any plan for how the Navy can “integrate” and what this actually means for other U.S. services, and strategic partners. In fact, it states that,

“America cannot cede the competition for influence. This is a uniquely naval mission. A combat-credible U.S. Navy—forward-deployed and integrated with all elements of national power—remains our Nation’s most potent, flexible, and versatile instrument of military influence. As the United States responds to the security environment through integrated deterrence, our Navy must deploy forward and campaign with a ready, capable, combat-credible fleet” (p.5)

Its approach to integration is indicated by other statements that single out the Navy without referring to any other service like: “The Nation cannot afford to cede influence to China or Russia. Nor can it afford to lose combat credibility. We must deliver a Navy designed to deter conflict and help win our Nation’s wars as we maintain a global posture to assure our prosperity. Our national security depends on it.” (p. 12)

5. AI, Cyber, Space, and JADO

The Navigation Plan does list many of the new technologies that are already reshaping military forces throughout the world, but it does not address the fact that most now have relatively short-term windows of predictability, and that some clear path is needed to coordinating U.S. and partner military efforts in new and exploratory ways. It does not address the real-world challenges caused by the fact that major breakthroughs are unpredictable by definition, and that the most strategy can do is focus on key areas of change, describe clear plans for action where immediate priorities exist, and single out the areas for future focus – the technologies NATO calls “disruptive.”

Once again, when the Navigation Plan does mention specific area of technology, it does so largely in terms of broad goals and buzzwords. (e.g. pp. 18-19)

As is noted throughout this critique, strategy documents that set broad goals for doing everything in unstated ways with unstated timelines and unstated implementation plans have little practical value. Good intentions alone do not address real world needs and priorities.

6. Net Assessment and the Threats the US and its Partners Must Face

The section on the “Security Environment” (pp. 4-5) highlights key issues, but in a way so lacking in detail and justification that it reads more like propaganda than a plan. There is no real net assessment of U.S. and partner capabilities to deal with present and project threats, and the ability – or lack of it – to deal with the probable changes in Chinese, Russian, and other hostile forces.

It does not summarize the ongoing shifts in Chinese sea, air, and missile power that are making a major threat, identify the problems emerging in the Persian/Arab Gulf and North Korea, the growing level of Russian and Chinese military cooperation in the Pacific, and the broader changes in Russian and Chinese nuclear and long-range strike forces. If anything, it implies that the Navy and SSBNs are the only major solution to modernizing “our nuclear command, control, and communications systems to ensure the United States can deter nuclear coercion and nuclear employment in any scenario (p. 6).”

Here, the new Japanese defense white paper – Defense of Japan 2022 – provides examples of short and long-term trend analysis that highlights the growth of key threats and the current military balance in summary terms as well as major future trends. It centers proposed spending and force development around the key challenges Japan’s forces must respond to and shows that a well-structured strategy paper can do so in an unclassified form that can help win the support of the public, legislators, and strategic partners.

7. Focusing on Strategic Partners and Other States

The Navigation Plan is US-centric to the point of neo-isolationism. It touches upon on strategic partnerships, but it does not single any out as part of a common effort and strategy, and skims over the need to focus on the need to reinforce regional influence on a political and civil level as well as a military one – which is a key aspect of successful sea power.

It ignores the need to reorganize our Atlantic and Mediterranean posture in view of the Ukraine war, and the need to work with NATO and other European allies in creating interoperable and effective forces at a time major efforts are needed to revitalize many NATO navies and work with Britain to shape its naval role in a post-EU world.

Similarly, it largely ignores the need to link the US naval (and joint) posture to our Pacific, Indian Ocean, and MENA strategic partners which still has at least equal priority. Once again the contrast with Japanese defense white paper – which does this – is striking.

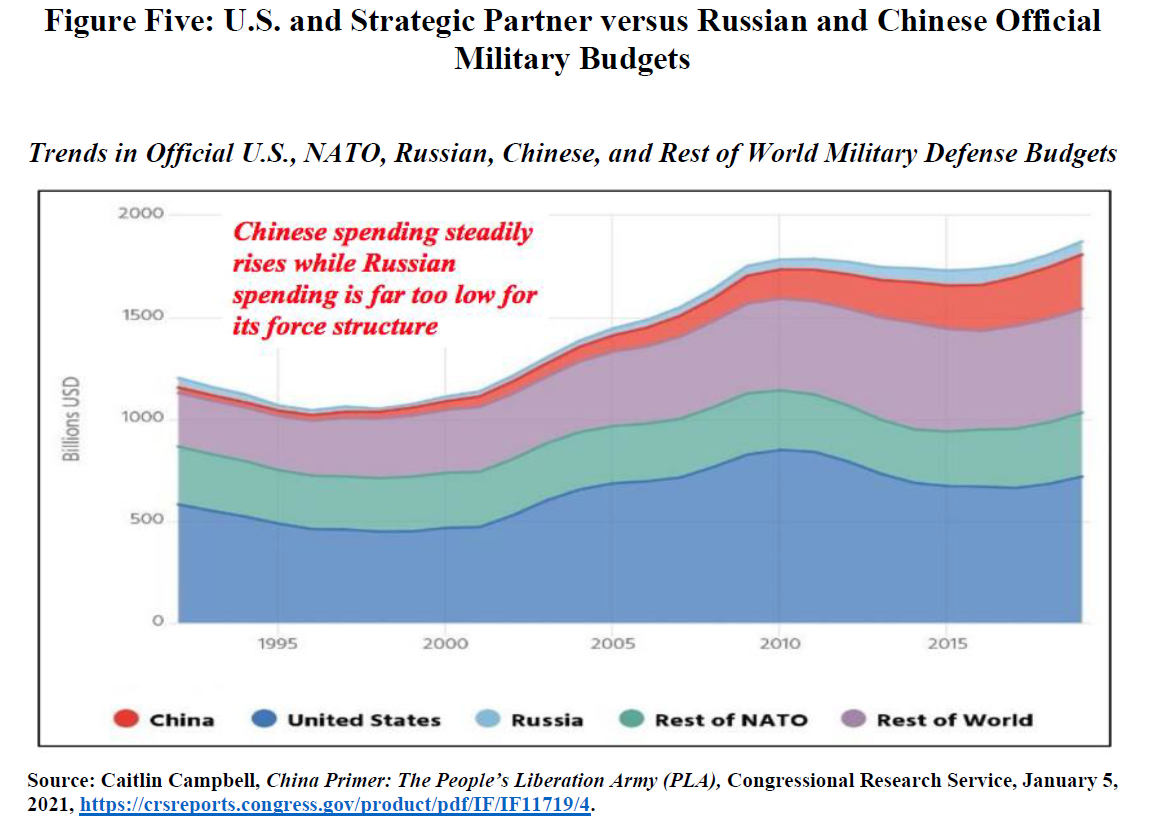

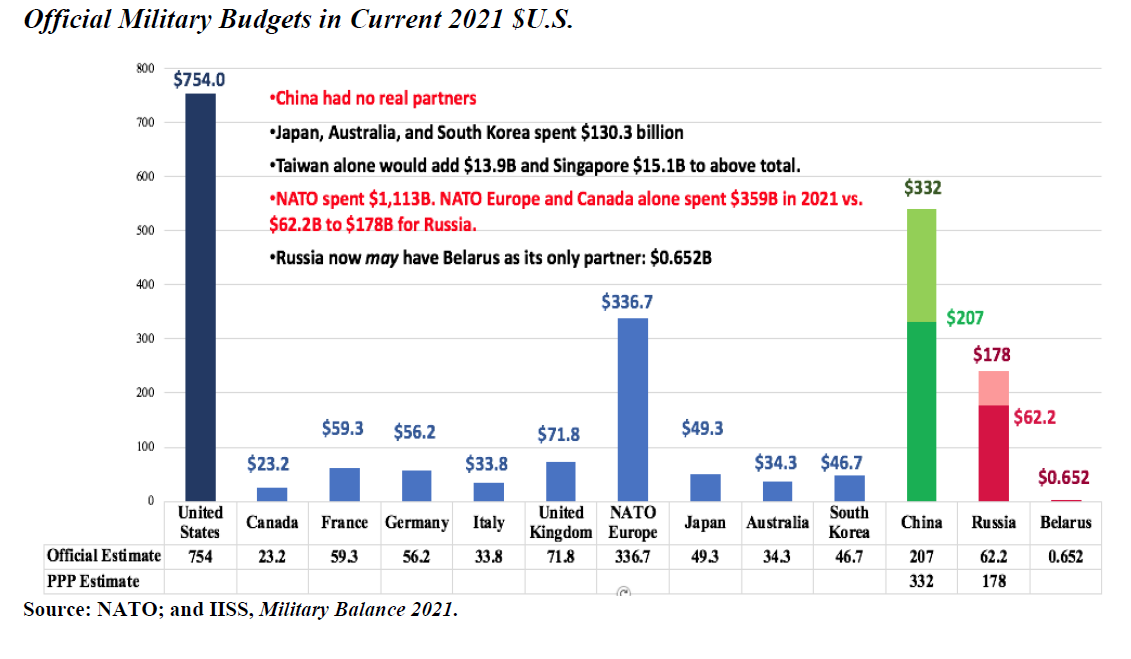

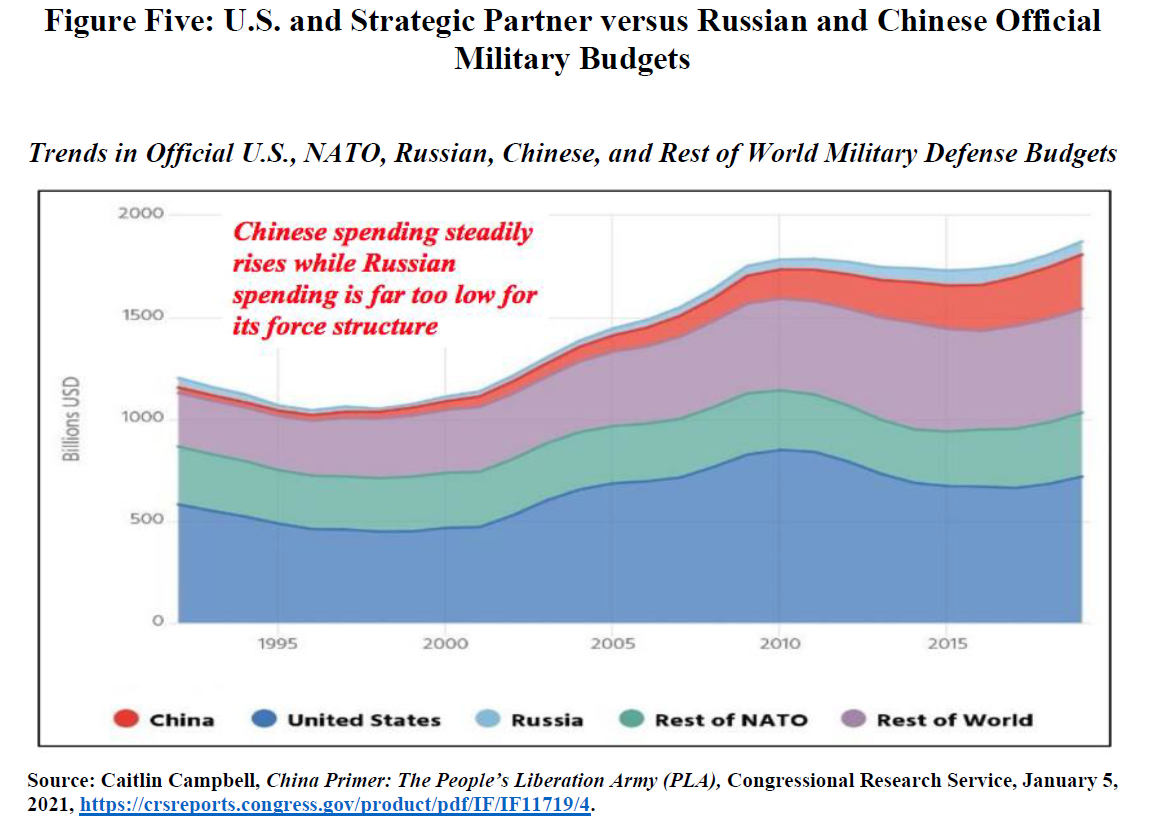

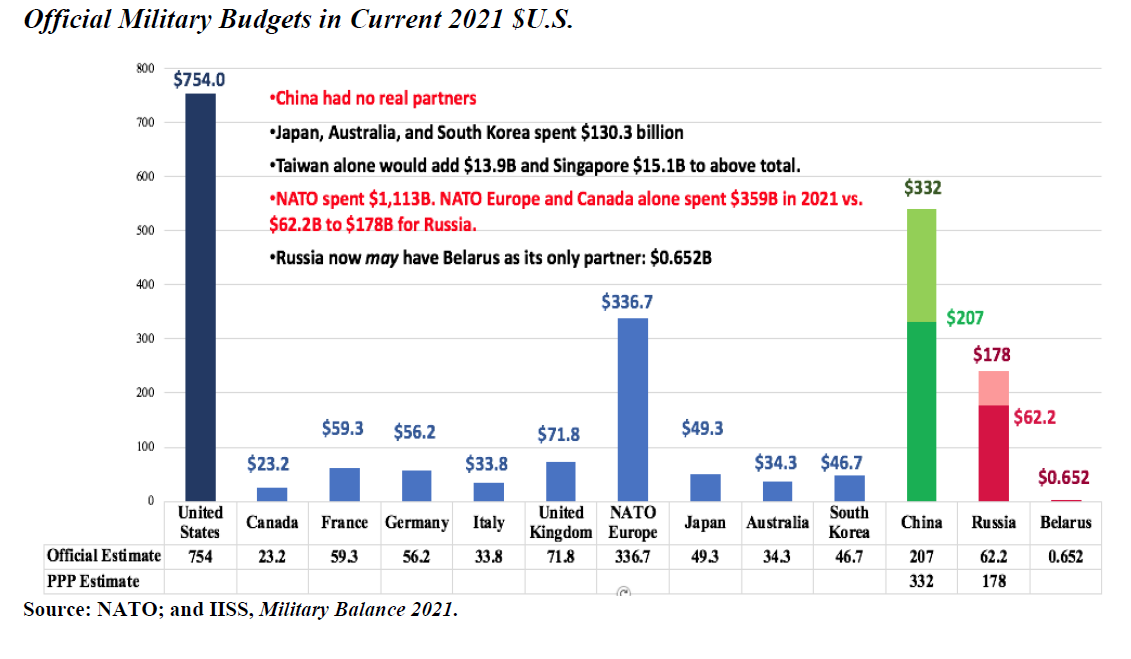

The financial value of close cooperation with our partners is illustrated by Figure Five. Partners are not only critical in terms of war fighting and deterrence. They can play a key potential rule in meeting future spending and economic challenges.

Anthony H. Cordesman is the Emeritus Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He has previously served in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the National Security Council, the State Department, and the Department of Energy. During his time at CSIS, Dr. Cordesman previously held the Burke Chair in Strategy. He is the author of more than 50 books, including a four-volume series on the lessons of modern war.

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (August 7, 2022) Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer USS Spruance (DDG 111) sails alongside Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) during an air power demonstration. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jeffrey F. Yale)