By Ben Claremont

The past several weeks have seen some extraordinary Russian naval activity.1 On 17 and 18 January 2021, six Russian amphibious warfare ships sortied from the Baltic Sea, passing through the Danish straits to the North Sea. On 24 January, TASS reported that over 20 surface combatants and auxiliaries sortied from the Russian Baltic Fleet.2 Recent satellite radar imagery of Baltiysk Naval Base in Kaliningrad shows only the two Neustrashimy-class frigates in port.3 This implies that all four Steregushchiy-class corvettes and several of the 21 smaller ships assigned to the fleet are at sea.4 In addition, major portions of the Northern, Pacific, and Black Sea Fleets have sortied, nominally as part of a large exercise.5 On 4 February, the six amphibious ships stopped for resupply in Tartus, Syria.6 Currently, they have transited the Turkish Straits and entered the Black Sea.7

Due to the build-up of forces on the Russian border with Ukraine and in Belarus, Russia’s amphibious forces have received a great deal of news coverage. This includes no less than eight articles in The Drive’s The War Zone and regular reporting from USNI News, Forbes, Radio Free Europe, the French Navy, and numerous other media outlets.8 The coverage has generally focused on their progress and the viability and possible locations of amphibious assaults on Ukraine. While the capabilities, location, and destination of these ships are important, their movements and possible targets must be contextualized; the Russian Military has a distinct understanding of and approach to amphibious warfare. It also must be kept in mind that these forces only augment existing capabilities in the Black Sea Fleet and so should not be used as an indicator of readiness to initiate conflict.

Most commentary on possible Russian amphibious assaults in a war with Ukraine suggests targets such as Odessa and Mariupol or describes them as a feint.9 In November, the Chief of Ukrainian Military Intelligence suggested that amphibious assaults would target Odessa and Mariupol.10 Responding to this in the January 2022 issue of Proceedings, Col. (Ret.) Phillip G. Wasielewski, U.S. Marine Corps, suggested that such assaults would be incredibly risky.11 Still, the idea of amphibious assaults to seize major cities persists.12 However, when this scenario is compared with existing Russian amphibious warfare capabilities, the Russian theory and practice of amphibious warfare (and its Soviet antecedent), and the larger Russian deployment of forces, it becomes clear that Mariupol, Odessa, and other major urban areas or ports are unlikely targets for the Russian Naval Infantry. Conversely, it is unlikely that such forces are only a bluff, feint, or ruse.

February 9, 2022 video by Ihlas News Agency entitled (in Turkish), “Russian Warships Advancing From The Dardanelles To The Black Sea One After One.”

Capabilities

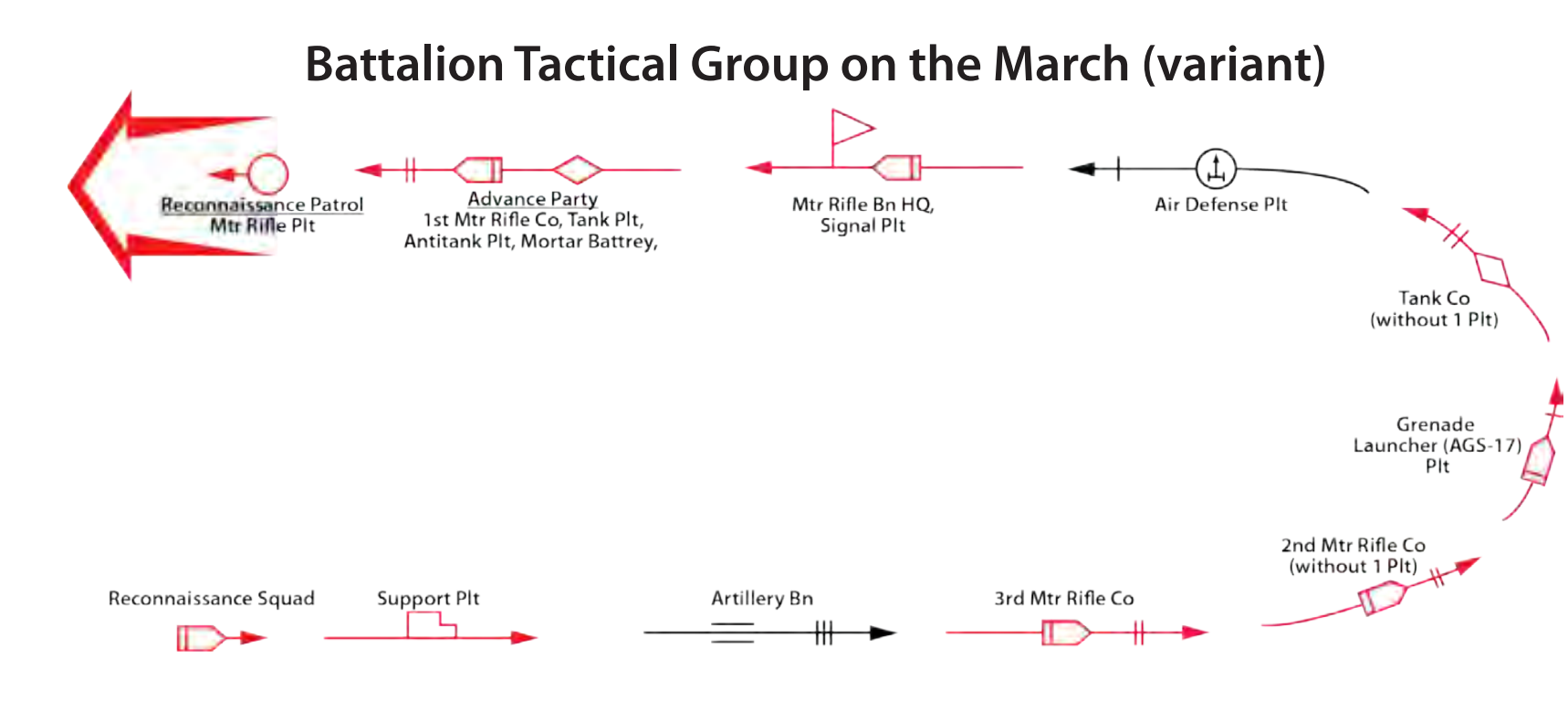

Russia’s amphibious ships are moving in two groups with an estimated capacity of two regular battalions — one tank and one motorized infantry— with some space for artillery and air defenses. Alternatively, the groups could carry a Battalion Tactical Group.

Group 1: Baltic Fleet14

- Пр.775/II [ROPUCHA-I] 127 Minsk

- Пр.775/II [ROPUCHA-I] 102 Kaliningrad

- Пр.775/III [ROPUCHA-II] 130 Korolyov

Group 2: Northern Fleet15

- Пр.775/I [ROPUCHA-I] 012 Olenegorskii Gornyak

- Пр.775/II [ROPUCHA-I] 016 Georgii Pobedonosets

- Пр.11711 [IVAN GREN] 017 Peter Morgunov

A Battalion Tactical Group (BTG) is a task-organized combined arms force created by augmenting a Motor-Rifle Battalion (MRBn) with tanks, artillery, electronic warfare capabilities, air defenses, and other modern conveniences necessary for the mission at hand.16 It is the smallest regularly formed combined arms force in the Russian military capable of independent action.17 It is only the latest form of a type of unit which the Russians — and Soviets before them — have been iteratively developing and adjusting since the Second world War.18 A 1989 survey of Soviet professional literature on the topic found that only 12 of the 551 examined battalion-level actions involved a battalion acting without attachments or support, and none took place after 1972.19

From analyzing Russian exercises, it can be inferred that these two groups can carry a BTG. Zapad 2021 featured an amphibious assault exercise in which four Ropucha-class tank landing ships (LSTs) and two Zubr-class landing craft air cushion (LCACs) landed a Naval Infantry force.24 The four Ropucha-class offloaded “more than 40x BTR-80” while the two Zubr-class LCAC offloaded supporting vehicles. A Russian BTR-mounted infantry battalion has 44 BTR-80 variants, meaning that four Ropuchas can carry the entire infantry landing force of a BTG. This leaves two landing ships for whatever forces are attached — likely a mixture of tanks, artillery, and air defense vehicles. While the contents of their holds are unclear, a BTG is well within the six ships’ capacity and congruous with the Naval Infantry’s most probable mission in conflict: supporting the Russian Ground Forces.

Theory and Practice

Whatever its size, this amphibious force is trained to conduct what the Russians call “десант” [desant]. Desant is the task of landing troops on the enemy’s territory to conduct combat operations.25 The role of the Naval Infantry in these landings is to support the action of the Ground Forces. The Russian Navy did not consider themselves able to conduct a brigade-scale landing — what they call an Operational Desant — in 2018, and there is no indication this has changed.26 The Kavkaz 2020 and Zapad 2021 exercises included landings by battalion-sized groupings. In particular, Zapad 2021 featured 4 Ropuchas landing a Naval Infantry Battalion while two Zubr-class landed the battalion’s attachments.27 This restricts the mission profile to Takticheskii Desant (Tactical Desant), defined as: desant used in an offensive battle or operation to destroy important enemy targets in the tactical and close-operational depths, preventing the maneuver of enemy troops and ensuring the high rate of advance.28

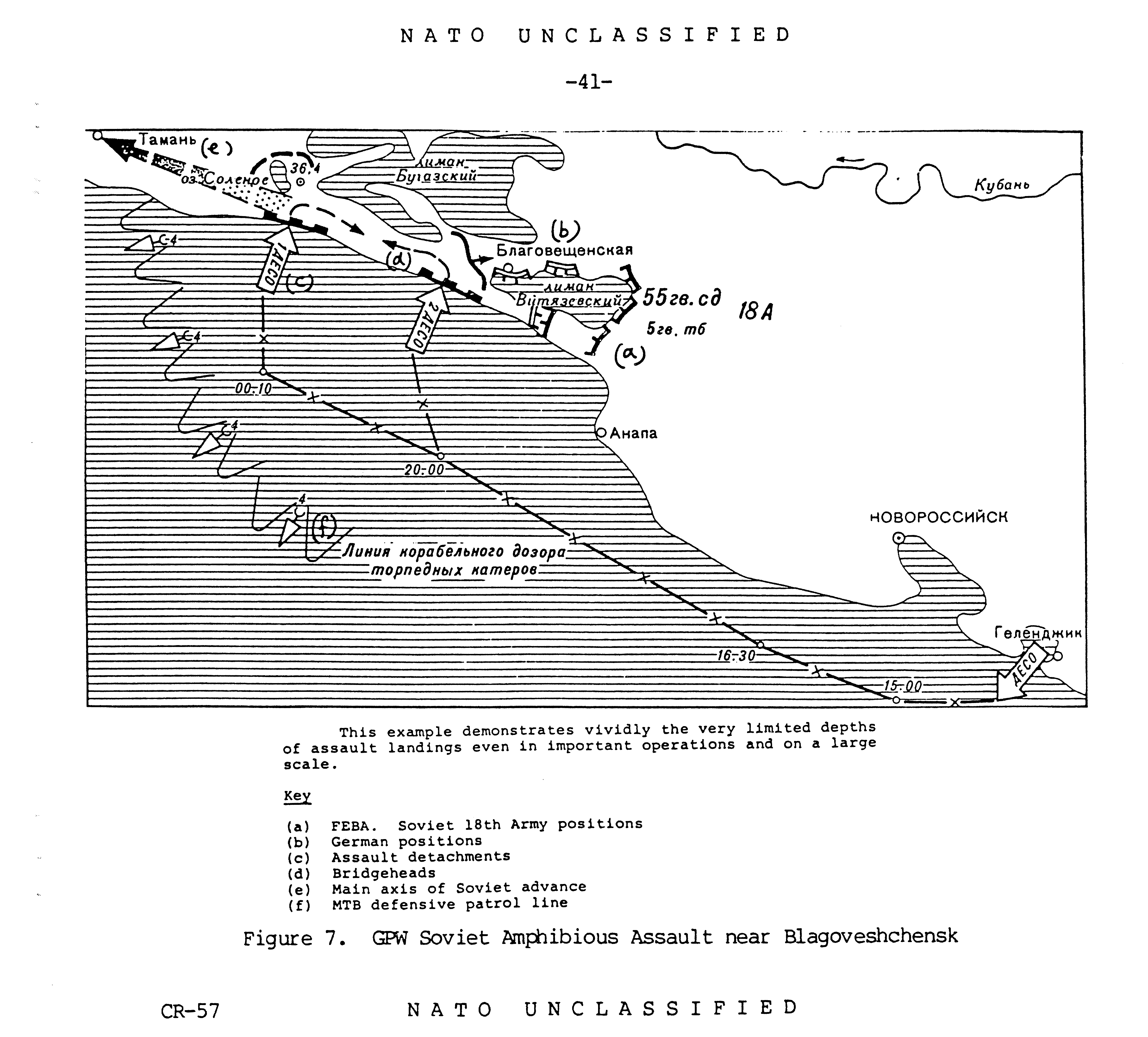

The archetypical Soviet-Russian Tactical Desant is conducted in the tactical depth to outflank an enemy defense or insert a force acting as a forward detachment for the main forces attacking along a coastline.29 These are both viable missions for a Naval Infantry BTG. The location of such a landing is dependent on the disposition of enemy forces and the landing force mission. However, the Russians do believe that surprise (Внезапность) is a prerequisite of success.30 Whether or not it is still possible to conceal an amphibious landing, it is likely Russia would seek to conceal the beachhead and axis of the main effort.31 A common method to achieve this is by presenting the enemy with information which confirms pre-existing incorrect assessments of the time, place, and scale of a landing. Operation Fortitude is a classic example of this technique, though Soviet practice went further, often conducting a secondary landing to continue the deception or split enemy attention.32 Examples of this include the January 1943 Taman landings by the 47th Army, the April 1942 Murmansk Offensive by the 14th Army, and the October 1944 landing at Malaya Volokovaya by the 63rd Naval Infantry Brigade.33

The Soviet-Russian school of amphibious assault also heavily features vertical envelopment by airborne or heliborne forces to support the landing. This could either be in support of seizing an initial beachhead or to assist the Naval Infantry force in achieving their objectives. One of the most common uses of vertical envelopment seen in Russian amphibious assault theory and practice is an initial landing of infantry and combat engineers to clear obstacles and provide security for the beachhead.34 This initial landing may be supplemented or replaced by landings from small assault boats, such as the Pr.03160 Raptor-class.35 Four of these boats were spotted on 30 January moving on the M4 highway between Moscow and Krasnodar via Rostov-on-Don and Voronezh.36

All six amphibious ships appeared loaded in pictures captured as they transited through Denmark.37 In addition, Frederik Van Lokeren noted that when the Northern Fleet Ropucha-class LST Aleksandr Otrakovsky and Georgiy Pobedonosets and Ivan Gren-class Pyotr Morgunov entered the Baltic on 11 January, “It appear[ed] that both Ropucha class vessels are fully loaded, with the RFS Pyotr Morgunov being partly loaded,” and that on 13 January at least a company of BTR-mounted Naval Infantry was seen leaving their barracks in Baltiysk.38 It is therefore possible that the BTG consists of Baltic Fleet Infantry and supporting assets from the Northern Fleet’s Naval Infantry units.

Conclusions

While these movements are cause for concern, the initiation of armed conflict is unlikely to be contingent on these forces. The Black Sea Fleet has seven LSTs organic to its forces, three Alligator-class and four Ropucha-class.39 Each Alligator-class has double the capacity of a Ropucha-class.40 These seven ships have far more capacity than the six amphibious ships from the Baltic and Northern Fleets.

While amphibious landings could undoubtedly assist in destabilizing Ukrainian defenses, the Russians have amassed a preponderance of forces near the Ukrainian border, equivalent to 12 divisions or over 75 BTG.41 It is highly unlikely that Russian planning is reliant on whether they can put two BTG over the shore instead of the single BTG they are currently able to land, or even whether they can land one maneuver battalion when they have deployed 12 divisions.

In sum: the Russians have moved loaded amphibious ships that double their landing capacity in the Black Sea to two BTGs. If they do conduct a landing, it will almost certainly be in support of the Ground Forces, not an attempt to seize major urban areas by coup de main. It is unlikely that Russian offensive plans are contingent on the amphibious forces which just entered the Black Sea. These forces represent less than 1/75th of deployed Russian maneuver battalions and far less than one percent of deployed Russian combat power when air assets and high-level indirect fire assets are considered.

The build-up phase of the Russo-Belarussian joint exercise was scheduled to end on 9 February. This is the date by which experts such as Rob Lee have stated that Russia’s deployment of forces would likely be complete.42 At the time of publishing on 10 February the Baltic and Northern Fleet amphibious forces have arrived in the Black Sea. However, these forces would only augment existing Black Sea Fleet capability and so should not be used as an indicator of Russian readiness for offensive action. On the other hand, these amphibious forces are unlikely to be a feint; the Russians have demonstrated the capability to land battalion-scale forces in the region, and such a landing fits into their theory and practice.

Benjamin Claremont graduated with an MLitt in Strategic Studies from the University of St Andrews School of International Relations in 2021. His dissertation, Peeking at the Other Side of the Fence: Lessons Learned in Threat Analysis from the US Military’s Efforts to Understand the Soviet Military During the Cold War, explored the impact of changing sources, analytical methodologies, and distribution schemes on US Army and US Navy threat analysis of the Soviet Military, how this impacted policy and strategy, and what this can teach in a renewed era of great power competition. He received his MA (Honours) in Modern History from the University of St. Andrews. He is interested in Strategy, Operational Art, Naval Warfare, and Soviet/Russian Military Science.

References

[1] https://www.c-span.org/video/?517418-1/defense-department-briefing

[2] https://tass.com/defense/1392417

[3] https://twitter.com/RALee85/status/1485698678979538951?s=20https://twitter.com/GrangerE04117/status/1485696134278696960?s=20

[4] These comprise: 4x Nanuchka-III-, 6x Parchim-, 2x Buyan-M-, 3x Karakurt-, and 6x Tarantul-class corvettes and missile boats. The fleet flagship, the Sovermenny-class destroyer Nastoychivy is currently in refit.

[5] https://tass.ru/armiya-i-opk/13479285

[6] https://ria.ru/20220204/korabli-1770989423.html

[7] https://twitter.com/SAMSyria0/status/1490018038363664385; https://twitter.com/ethevessen/status/1489987246778466311; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDFnDseNptw; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qmPmXkDvt5g;

[8] https://news.usni.org/2022/01/21/russian-navy-announces-more-major-fleet-exercises-as-drills-end-with-china-iran; https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2022/01/18/russia-has-rehearsed-an-amphibious-invasion-of-ukraine-but-thats-the-least-of-kievs-problems/?sh=3129cb5438cd; https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-russia-sea-attack/31670910.html; https://twitter.com/EtatMajorFR/status/1484901686808358915?s=20&t=_Y4i8xiOZag0SdywGQsXXQ; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/23/russian-ships-tanks-and-troops-on-the-move-to-ukraine-as-peace-talks-stall; https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/17403270/russian-warships-escorted-english-channel-royal-navy/; https://twitter.com/trbrtc/status/1486745542709317634

[13] https://twitter.com/tekmic64/status/1483049987315580929; https://twitter.com/tekmic64/status/1483405897640599554?s=20

[14] https://twitter.com/COUPSURE/status/1484260688893820944

[15] https://twitter.com/COUPSURE/status/1483410761422712835?s=20

[16] Grau and Bartles, Russia’s View of Mission Command of Battalion Tactical Groups (2016), p. 5-7

[17] Grau and Bartles, Russian Way of War (2017), p. 37-40

[18] The Soviets habitually task-organized their battalions into combined arms formations throughout the Great Patriotic War. Grau, Combined Arms Battalion, p. 31

[19] Les Grau Soviet Combined Arms Battalion – Reorganization for Tactical Flexibility, p. 14.

[20] Grau and Bartles, Russian Way of War, p. 224

[21] Ibid p. 210

[22] Ibid p. 148, 267, 334

[23]As a task organized group these numbers are only loose estimates.

[24] https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/2021/09/14/zapad-2021-day-3-september-12/

[25] VES 1986 p. 229 Note that desant is seen as the same fundamental activity no matter the mode of transport.

[26] Bartles, Russian Naval Infantry – Increasing Amphibious Warfare Capabilities, Marine Corps Gazette, (Nov. 2018), p. 64

[27] https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/2020/09/27/kavkaz-2020-september-23-day-3/ ; https://russianmilitaryanalysis.wordpress.com/2021/09/14/zapad-2021-day-3-september-12/ Note that this was not described as a BTG landing. This is perhaps due to the limited support or specific mission planned.

[28] Военный энциклопедический словарь 1986 edition (VES86), p. 229.

[29] Further Reading can be found in Leavenworth Paper 17: The Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation and SSRC Report CR-57 Soviet Amphibious Operations: Implications for the Security of NATO’s Northern Flank.

[30] https://encyclopedia.mil.ru/encyclopedia/dictionary/details.htm?id=4272@morfDictionary; this is nearly unchanged from the late-soviet definition. For more discussion see: FM 100-2-1 (1990) p. 1-35:1-41 and Советская военная энциклопедия 1979 Edition (SVE79) Vol. 2, p. 161-163

[31] Soviet Amphibious Operations p. 58-59

[32] Soviet Amphibious Operations p. 59

[33] Soviet Amphibious Operations p. 59, Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation p. 89-91

[34] https://youtu.be/jzv-MnTKfdM https://youtu.be/jzv-MnTKfdM Vertical envelopment is often supplemented by personnel landed from small assault boats like the Pr.03160 Raptor-class.

[35] https://youtu.be/_dF0Db8UWZE

[36] https://twitter.com/GirkinGirkin/status/1487773497346732036?s=20&t=Q8Hrhe9cL7MioCgIpcQoxg

[37] https://twitter.com/tekmic64/status/1483049987315580929 A friend in the Danish Navy who saw them sortie confirmed they were lower in the water than typical even for exercises.

[38] https://russianfleetanalysis.blogspot.com/2022/01/russian-naval-infantry-january-2022.html, citing https://twitter.com/The_Lookout_N/status/1481373264471629826

[39] The Alligator-class is known to the Russians as Project 1171 Tapir.

[40] Apalkov, Landing Ships p. 8-9

[41] https://rochan-consulting.com/tracking-russian-deployments-near-ukraine-autumn-winter-2021-22/; https://twitter.com/RALee85/status/1486539799100067845?s=20; https://video.foxnews.com/v/6295567325001#sp=show-clips

[42] https://twitter.com/RALee85/status/1486398656513257479?s=20&t=ep54Rvt57aazDvjbwTAvVg

Featured image: A photograph of Russian Ropucha-class Korolev followed by the French patrol vessel Flamant while transiting the English Channel (Credit : https://twitter.com/COUPSURE/status/1484260688893820944/photo/)