By Dmitry Filipoff

Introduction

“I strongly encourage you to read, think, and write about our naval profession.” – Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson with Lieutenant Ashley O’Keefe, “Now Hear This – Read. Write.Fight.”1

Earlier this month, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) of the U.S. Navy Admiral John Richardson published, with Lieutenant Ashley O’Keefe, “Now Hear This – Read. Write. Fight.” In this piece, the CNO issues a call to read and write: “I want to revitalize the intellectual debate in our Navy. We all—officers, enlisted, and civilians—need to develop sound and long-term habits for reading and writing during the entire course of our careers.”2 The CNO hinted at several initiatives that aim to promote public discussion and publication accessibility. The CNO plans to create an e-book program, share what he considers “a canon of classic works,” and “open up a way for all of us to talk about what we are reading.” These plans should surely excite those who are invested in the Navy’s success.

There is more that can be done to operationalize this call to read and write. The Navy needs a strategy to cultivate intellectual development and encourage sailors to read and write more. As the CNO has just done, the Navy must continue to express the importance of writing to the Navy’s future. The service must improve its self-awareness of its own intellectual culture and mold it to encourage better habits of thought. The Navy must develop means to extrapolate value from published work and public discussions. Proper incentives should be instituted to show sailors that publishing is in fact career-enhancing and serves the Navy’s interests. There is a lot that can be done.

There is also more we can do here. As CIMSEC’s editor-in-chief, I will describe how our audience has made strong contributions to the Navy’s public discussions, what makes CIMSEC an ideal platform for facilitating such debate, and what we will do to improve.

Why the Navy Must Read and Write

“You will learn that bravery is not enough – and that you must do your utmost by professional study and reading of history to perfect your readiness to serve your country.”- Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, “Address to the Japanese Training Squadron in San Francisco, August 1964.”3

Active public discussion will help the Navy make the most of its best resource, its people. Public discussion will help mitigate the inherent disadvantages in operating a large and compartmentalized institution. Healthy reading and writing habits build better warfighters. It will better connect the fleet and make issues relevant to more stakeholders.

At any given time, there are innumerable conversations happening on how to make the Navy better. These conversations include interpretations of past decisions and assessments of present challenges, with an eye towards the future. These are among the most exciting and consequential conversations of individual careers and even entire generations of sailors. They are being spearheaded by the Navy’s best and brightest across numerous commands and institutions. But most of these conversations occur within meetings, emails, or in some other closed format that does not fully engage all those who are interested and able to make the Navy better. Admiral Jim Stavridis, a strong proponent of reading and writing, recognized this issue, “We often express these ideas and observations in wardroom discussions, which are critical elements of personal and unit development. But these discussions usually make local impact only and stay within the lifelines of the ship or unit.”4 The fruits of experience may be lost in the form of insights that were never put forward in public writing.

Public discussion will broaden the impact of promising ideas and successful solutions. The CNO’s plan to “open up a way for all of us to talk about what we are reading” may be the most exciting initiative as it will help ensure great writing gets noticed regardless of where it gets published or who reads it.5 An organization that can rotate personnel assignments as often as every 18 months may impair the development of its own institutional knowledge and the continuity of expertise. Reading lists and well-read personnel can mitigate this challenge. Ultimately, public discussion will help the Navy identify more of its best and brightest and direct them towards where they can make the greatest impact.

Robust public discussion is important in keeping to a theme of operating in a complex, highly interconnected world. It will empower junior leaders that are closer to problems and their potential solutions. Disruptive challenges may arrive spontaneously, and innovative solutions can come from any rank. Publications can provide early warning and unbiased assessments. Robust debate can help process and make sense of information overload as strong arguments streamline options. Additionally, it can check groupthink and discourage complacence. Public discussion can provide a venue for introducing ideas and information when bureaucracy is too slow or unreceptive. It can connect everyone regardless of rank and command, thereby providing a level playing field where ideas can stand on their own.

Reading and writing hones critical thinking skills that improve warfighting proficiency. Among other things, writing improves self-awareness, information processing, and the ability to anticipate. Reading and writing habits will enhance the strategic communication capabilities that are growing in significance in today’s complex security environment. The same skills will better enable commanders to lead highly trained personnel and fully understand their leadership’s intent.

It is a step up to go from reading to publishing one’s own work and joining the debate. Publishing is an act of leadership. It requires initiative, commitment, and courage. Initiative, because publishing is an independent act that seeks to be forward thinking. Commitment, because ideas must be defended in depth once published. Courage, because the decision to publish is made in spite of the nagging insecurity that written work will never be as perfect as the author would have ultimately desired. Combine these themes, and it becomes apparent that publishing provides valuable experience in dealing with risk. Publishing develops positive leadership attributes.

Better reading and writing habits will connect the fleet by raising awareness of shared challenges and the interesting and dedicated work occurring at any time across the numerous institutions and commands that support the Navy. It will broaden perspectives and connect expertise. For example, the naval aviation community should closely follow the distributed lethality concept being spearheaded by the surface warfare community in order to explore new concepts of operation for carrier and land based aircraft under a new warfighting construct. Coast Guard operating challenges and lessons learned could inform those operating on the frontlines of the South China Sea. The effectiveness of the joint force would be greatly enhanced by increasing awareness of the challenges, modernization programs, and operational contributions of all the services. A greater appreciation and knowledge of foreign policy will help service members justify their efforts and sacrifices.

The value of reading and writing is apparent. How can the Navy encourage more of it?

Reading

“Thanks to my reading, I have never been caught flat-footed by any situation, never at a loss for how any problem has been addressed (successfully or unsuccessfully) before. It doesn’t give me all the answers, but it lights what is often a dark path ahead.” – General James Mattis, “With Rifle and Bibliography: General Mattis on Professional Reading.”6

Steady reading habits can be encouraged by fostering specific interests and having commands build reading lists that are directly relevant to their mission sets. Reading lists should include alternative forms of material besides books, with an emphasis on digital content. Additionally, the unique role of public affairs personnel can be expanded to facilitate more reading.

Reading lists should not be something that just the CNO assembles and publicly lists, but something that every command puts together. Commands should actively seek out publications that reinforce the subject-matter expertise that supports their specific missions and build their own public reading lists. Captain Wayne Hughes’ (ret.) Fleet Tactics: Theory and Practice should be required reading at the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center. Personnel at Pacific Command and Pacific Fleet would benefit greatly from having read Captain Bud Cole’s (ret.) Asian Maritime Strategies. Those with the Fifth Fleet would be well served by David Crist’s Gulf of Conflict: A History of U.S.- Iranian Confrontation at Sea. Sailors will be more likely to invest time in reading if the publications singled out are clearly and specifically relevant to their responsibilities. Cultivating specific interests can build reading habits that support professional obligations.

Reading lists often suffer from a big drawback in that they solely consist of books. By confining lists to just books, other types of content are neglected. Reading lists should strive to include articles and recognize the value of media in other formats such as videos and podcasts. Stimulating content is clearly not limited to just written work in the form of books.

Digital content should be prioritized in order to maximize sharing and accessibility. It is admirable that the Chief of Naval Operations Professional Reading Program (CNO-PRP) launched in October 2012 purchased 22,000 books, created 420 lending libraries, and disseminated books across the fleet and around the world.7 But only the resources and influence of the CNO could make such a broad effort possible. If a more junior leader saw great value in disseminating a certain publication within their respective command, the cost of ordering enough books could be prohibitive. With the advent of e-books and audiobooks, writings that used to be only in book form can now be accessed electronically. Navy leaders should take their reading recommendations into the digital age and ensure that the majority of the content promoted can be accessed electronically.

Public affairs personnel have an important role to play in strengthening reading habits, as they often collect publications and disseminate them within their respective commands. Public affairs officers (PAO) should be highly interconnected with one another in order to facilitate sharing and awareness of publications. They should be familiar with the many organizations within the Navy in order to know which would benefit most from having read a certain publication. They must have a keen sense of relevance. Additionally, they should be familiar with the many news outlets, periodicals, think tanks, and other forums where issues of import to the Navy are being broached. Public affairs staff should be incredibly well-read and up-to-date on these outlets in order to sift through content in search of the gems that are worthy of sharing and dissemination. They can help build public reading lists. The roles and responsibilities of PAOs should be reviewed and appropriately modified to best connect commands to public discussions.

Solid reading habits will improve professionalism and connect the fleet. All writers are readers, but encouraging sailors to go from following the discussion to contributing to it poses a greater challenge.

Writing

“If you have not written much, I urge you to get started.”- Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson with Lieutenant Ashley O’Keefe, “Now Hear This- Read. Write.Fight.”8

What will ultimately compel sailors to turn a flash of inspiration or a deep seated curiosity into written work is the right intellectual culture and receptive leadership. The Navy must recognize sources of inhibition in order to mold culture and educate sailors on the process of writing. The Navy should develop a real system of incentives, feedback, and recognition to assimilate public discussion into its decision making and motivate individuals to write.

First, sailors must understand what they can write about. The answer is almost anything, and the call to write applies to everyone. However, the nature of what junior and senior leaders can write about differs. Junior leaders can produce effective critiques and local assessments as their fresh perspective allows them to recognize issues that more senior leaders may not detect. They enjoy plenty of latitude in regard to what they can write about. On the other hand, senior leadership operates under constraints that are not necessarily cultural. For example, flag officers cannot credibly publish work that ends with the disclaimer, “These views do not represent the Department of the Navy” because of their significant institutional responsibilities. But while they cannot openly challenge policies and programs, senior leaders can detail the important and interesting work they lead, reflect on progress, highlight obstacles overcome, and acknowledge challenges. There are many institutions working to make the Navy better. Public discussion will allow their stories to be told. Leaders should also be willing to justify and defend decisions in writing, much as they already do in testimony before elected officials. While it is understandable that the military need not operate as a democracy, public writing will allow junior and senior leaders to better understand one another and voice their honest concerns.

Classification presents a challenge. Protecting classified information is a responsible concern, but it encourages certain intellectual habits that inhibit the inclination to write. For example, individuals should not assume that everything of importance is being examined or discussed by somebody somewhere. Despite the numerous problem-solving and innovating institutions that contribute to the Navy’s future, there will still be issues that are not under review. Classification encourages this assumption because many sets of problems and their potential solutions qualify as secrets. This in turn may lead would-be writers to believe that because they do not have all the relevant inputs, their analyses would be critically flawed without compromising classified information. This may also create the insecurity that even if they do publish, there are those out there with access to classified material that could readily disprove them. These inhibitions must be overcome. Top priority must be placed on educating sailors on the regulations that affect public writing and showing them how to protect classified information while still publishing meaningful work.

The Navy must recognize the highly uneven intellectual culture within its institutions and communities. Academic institutions such as the Naval War College and the Naval Postgraduate School regularly publish high quality publications that should be read across the fleet. But in order to operationalize the CNO’s call to read and write, institutions across the Navy that do not traditionally publish must augment their culture in order to facilitate greater critical thinking and the willingness to put it into writing. The Navy should survey its various communities and commands to understand trends in the propensity of writing as well as reading preferences. STEM majors may differ in their inclination to write versus those educated in the humanities. Publishing habits may differ between the surface warfare community and the undersea community, officers versus enlisted, train and equip and operational, etc. Such a survey could reveal differences in intellectual culture and help aim targeted effort.

The Navy must assess the actionable value of exceptional writings, and be willing to turn written insights into decisions. People will write better and more often if they know there is real potential for their ideas to have an impact. Writers also very much enjoy receiving confirmation that they are actually being read. Where possible and appropriate, public affairs personnel should help writers learn where they are being read and by whom.

Writing should be actively promoted as career enhancing. The Navy should officially recognize written work as a professional accomplishment. The Navy can highlight where initiative in the intellectual sphere reaped rewards for the fleet in the past. The aforementioned reading lists can play a role in this by including publications that have made strong contributions to public discussions and fomented real change. Honoring those that have contributed brilliantly to public discussion and spurred real action with their writing will set a standard and show that leadership is paying attention.

Setting this strong standard is paramount. Rehashing common sense principles and stating the obvious is all too common in military writing. This is a symptom of an intellectual culture that favors conformity over originality. Writings should strive to inform, analyze, and provide insight. Discussions have context, history, and evolve through time. The prerequisites for making a meaningful contribution include a willingness to perform intensive research and the intellectual honesty to recognize the limits of one’s own understanding, where the latter guides the former.

Public failure must be made acceptable if there is to be growth. Negligent mistakes should be separated from genuine attempts to succeed. In the Navy today, sailors fail against one another in exercises, simulations, and other forms of competition. These are critical learning experiences that involve extensive feedback and reflection. That same honest willingness to help one another improve and become better warfighters should color the give-and-take of intellectual discussion. Yet these discussions should feature the intense competitive spirit that animates sailors to be at their best.

Meaningful writing will at times require standing up to one’s own institution, which is why it requires courageous leadership. But this requirement deters many would-be writers because military culture is not usually receptive to bottom-up challenges coming from within. Admiral Richardson recognizes this problem as he advocates that “…we need to ‘protect’ our best thinkers from a system that can be intolerant of challenge” and that “…senior leaders must not confuse respectful debate with disloyalty. Sometimes the junior person in the conversation may have the best idea.” This is an age-old problem that has hindered the Navy’s progress before. In an article series recounting the great frustration a young and persistently publishing William Sims experienced with an unreceptive Navy bureaucracy, Lieutenant Commander B.J. Armstrong made the important point that “Having senior leaders that listen, and who become the champions of the great ideas of their subordinates, is just as vital as having junior personnel with innovative ideas.”9 William Sims went on to become known across the fleet “the man who taught us how to shoot.” It would be ironic and to its own detriment if the Navy wanted bravery from its people in combat but not in thinking. Navy leadership at all levels must demonstrate that it is listening with intent.

Lastly, sailors need an understanding of the variety of outlets that are willing to publish their writings. Public affairs personnel can help by maintaining contacts with various editors and ensuring that regulations are being followed throughout the editorial process. It is important that at least several outlets be considered in order to afford writers flexibility since publishing practices and timelines can vary widely. When it comes to helping sailors get published and noticed, we feel we have a superior system here at CIMSEC.

CIMSEC’s Role

“CIMSEC is establishing itself as an intellectual powerhouse in maritime matters…”-Vice Admiral Thomas S. Rowden, “Distributed Lethality: An Update.”10

CIMSEC’s format and readership makes our community a strong player in public discussions on naval affairs, maritime security, the Asia-Pacific, and general defense and foreign policy. CIMSEC is unique in that virtually all of CIMSEC’s articles are by those who wish to use the website as a platform for their ideas, and not by our own cadre of dedicated volunteers.

CIMSEC publications feature a neutral, academically informed tone devoid of cynicism. Our non-profit status eases regulatory concerns. We have no paywalls, and our content is produced as a steady yet flexible stream rather than as a periodical. This allows us to rapidly engage with contributors. From first draft to final posting, getting published on CIMSEC usually only takes a few weeks and sometimes within days. Our monthly topic weeks allow us to focus attention and analysis on issues that are deserving of greater prominence, or engage the community in ongoing discussions on high profile topics. CIMSEC’s editorial team understands the issues and is always accessible to prospective contributors. We enjoy the great privilege of facilitating the ideas and writings of others.

We are especially proud of our audience. We count active, reserve, and retired naval personnel among our most dedicated readers and writers. CIMSEC contributors can rest assured that their publications are being read and shared by their peers across the fleet and other naval stakeholders, including institutions that are helping determine the future of the Navy.

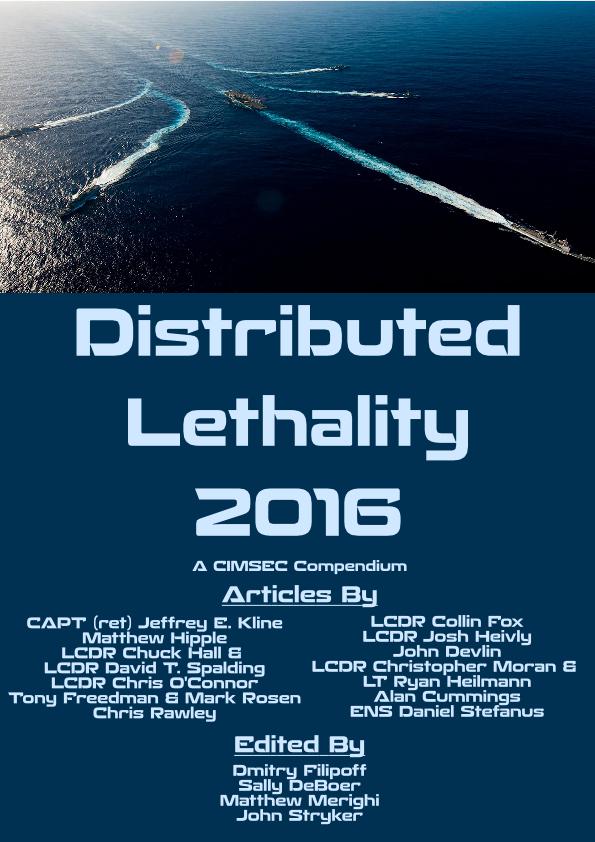

This last point is proven through one of our recent successes. In February of this year, the Navy’s Distributed Lethality Task Force partnered with CIMSEC to launch a topic week. The Task Force produced the Call for Articles where it outlined various questions of value to the development of the distributed lethality concept that is guiding the Navy’s effort to reinvigorate its offensive anti-surface warfare capability.11 The response from the CIMSEC audience was tremendous. Twelve articles published a little less than a month later. The contributors included a mixture of active duty, reserve, and retired naval officers. They represented various communities from within the Navy, and rank ranged from O1 to O6. They addressed what Captain Peter Swartz (ret.) has described as “the essential questions of the profession,” namely “operations,” “techniques,” “force packages,” and “who should decide?” 12 Their insights were remarkable, and the Distributed Lethality Task Force’s partnership provided the assurance that they would be read by their target audience. Just a month later, our community succeeded again with a ten-article topic week on naval humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR). In other publications, junior officers have challenged leadership development practices, retired officers have drawn attention to lapses in institutional memory, and senior leaders have updated their visions of the future. CIMSEC’s ability to make significant contributions to public discussions of import to the Navy is proven.

We will be launching several initiatives to improve our ability to facilitate these critical discussions while reinforcing ongoing lines of effort. We will be releasing a CIMSEC reader survey to better understand our audience, solicit their feedback, and measure our impact. In addition to supporting our topic weeks, we will regularly post new Calls for Articles that solicit analysis on high profile developments and ongoing issues of interest to the CIMSEC audience. We will reach out to Navy institutions and commands to propose topic week partnerships and engage the CIMSEC community on their issues. We will continually update our PDF papers database with quality publications drawn from open sources and maintain it as a shareable learning resource. Finally, we will always maintain a link to the Write for CIMSEC page on our homepage to help prospective contributors get in touch with the editorial team and learn of the various ways they can contribute. By growing our efforts we hope to grow the discussion, and the Navy along with it.

Conclusion

“All of us owe it to our nation and those we lead, to begin a consistent practice of self-study.”- Joe Byerly, “Three Truths about the Personal Study of War.”13

Reading and writing will help sailors strengthen their appreciation of the centuries-old institution they proudly serve in. Robust public discussion will foment a constant learning experience that is as informative as it is problem-solving. However, it must be supported by vigilant self-awareness. Not only does there need to be public discussion on all things Navy, but there needs to be a discussion about how that conversation is being fostered and the value it contributes, just as the CNO has done. We need to read and write about reading and writing. Just as the Navy must always question the longevity of its advantages over adversaries, so it must also constantly reflect on the quality of its public intellectual debate. Just as the Navy seeks to draw as much value as possible from investments in people and machines, it should actively explore how to enhance and make the most of public discussions. These are not challenges to be solved by the end of one leader’s tenure or another’s. These are enduring imperatives that every leader at every level should be mindful of for as long as there is a Navy.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Nextwar@cimsec.org.

References

1. Admiral John Richardson with Lieutenant Ashley O’Keefe, “Now Hear This – Read. Write. Fight,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, June 2016.

2. Ibid.

3. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, “Address to the Japanese Training Squadron in San Francisco, August 1964,” Naval Historical Collection at U.S. Naval War College.

4. Admiral Jim Stavridis, “Read, Think, Write, Publish,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, August 2008.

5. Ibid.

6. Jill R. Russel, “With Rifle and Bibliography: General Mattis on Professional Reading,” Strife Blog, May 7, 2013.

7. John E. Jackson, “Reflections on Reading #19: Fleet Feedback,” Navy Reading.

8. Ibid.

9. Lieutenant Commander B.J. Armstrong, “Expertise, Voice, Grit, and Listening…A Look at the Possible,” United States Naval Institute Blog, June 2012.

10. Vice Admiral Thomas S. Rowden, “Distributed Lethality: An Update,”Center for International Maritime Security, March 12. 2015.

11. Ryan Kelly, “Distributed Lethality Task Force Launches CIMSEC Topic Week,” Center for International Maritime Security, February 1, 2016.

12. Captain Peter M. Swartz (ret.), “Let Us Dare to Read, Think, Speak, And Write,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, October 1998.

13. Joe Byerly, “Three Truths about The Personal Study of War,” From the Green Notebook, June 7, 2015.

Featured Image: (Jan. 30, 2010) Logistics Specialist Seaman Joshua Williams browses through books in the ship’s library aboard the aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Bradley Evans/Released)