By Dr. Ian Ralby

“Legal Finish” is a term that has become commonplace in maritime security circles around the world. It refers to the process of putting a maritime law enforcement action through a legal mechanism – whether a prosecution, administrative proceeding or other adjudication – that formally assesses offenses under national law and where appropriate, penalizes perpetrators. Legal finish has rightly been identified as crucial because merely disrupting illicit activities does little to deter future criminal conduct; only enforcing legal consequences changes the risk-reward calculus for nefarious actors. The problem, however, is that with all the focus on the legal finish, many states, international organizations, and “capacity building” partners have forgotten the legal start.

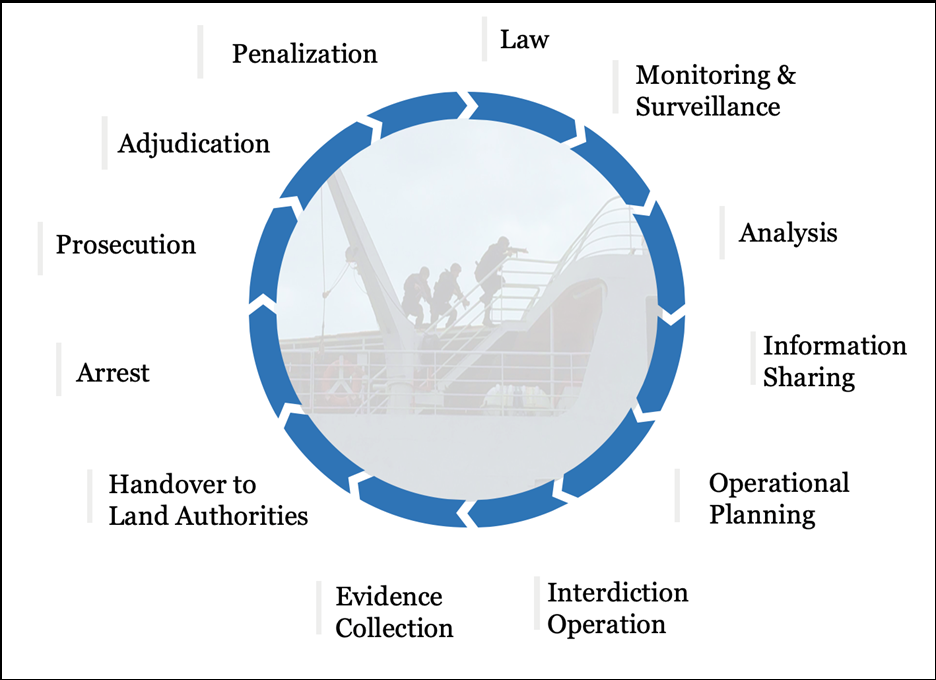

Maritime law enforcement is not a linear process, it is a cycle that starts and ends with the law. Recognizing its recursive nature is essential to establishing clear, consistent, and effective law enforcement and security operations.

To begin with, the law is the framework by which the maritime domain is assessed. Armed with the legal framework, maritime watchstanders can monitor and surveil the maritime domain, looking for any anomalies. Once they find those anomalies, however, a rigorous analytical process is needed to ensure that information is turned into understanding –about both what is happening on the water and what can be done about it. That analytical process, therefore, relies heavily on understanding the law. The key questions are:

- Is the anomaly desirable or undesirable? (Not all anomalies are undesirable).

- If it is undesirable, is it legal or illegal? (Not all undesirable matters have been addressed by the law).

- If it is illegal, is it actionable or not? (Does the state have the authority and jurisdiction to do something about it?)

- If it is actionable, is it achievable or not? (Does the state have the right physical capacity and capability to interdict the matter?)

- Even if it is undesirable, illegal, actionable, and achievable, would interdicting the matter be wise? (Is it worth the fuel, is it worth the risk, could there be geopolitical blowback, etc.?)

If the answer to any of these questions is “no,” then there should still be consideration of one additional question: “Is there anything else that could be done?” Watching the situation further, notifying other agencies, issuing a notice to mariners, or contacting neighboring states are all on the long list of other things that might be worth doing, short of pursuing an interdiction.

If the analysis suggests that an on-the-water operation might be warranted, then the analysts must have access to some sort of mechanism for sharing information with the proper decision-makers. Whether it is operative within an agency or across agencies, that cooperative mechanism must be repeatable (so there is consistency in how things happen), documentable (so there is a chance to learn from both successes and mistakes), and structured in such a manner that adequate information gets to the appropriate decision makers efficiently.

Once decision-makers have information about an anomaly that is undesirable, illegal, actionable, achievable, and worth pursuing, it is up to them to decide whether to conduct an operation. If they choose to do so, the operation must be planned and executed in a manner consistent with the law. That requires not only a clear understanding of the authorities that the respective agencies have for law enforcement, and the limitation of enforcement jurisdiction in the maritime domain, but also a sufficient grasp of all the elements of an offense to be able to identify and document those elements at sea. The collection and preservation of evidence in the maritime space is crucial, especially since revisiting a “crime scene” at sea is rarely, if ever possible. Thus, understanding the law at the operational stage – both in the sense of what the law enforcement officers do and concerning what they notice and record – is vital to legal finish. But that understanding is usually in the hands of completely different people than those responsible for the legal finish.

Importantly, arrests of people do not happen at sea. While it is possible to arrest a vessel, the suspects themselves are detained at sea and brought back to shore. Only once on shore are they handed over to land-based authorities who, on reviewing whatever evidence has been collected, then conduct an arrest or initiate an administrative proceeding. An arrest would then trigger the start of a prosecution, adjudication, and, if successful, penalization of the case. An administrative proceeding would similarly assess some sort of penalty. In either case – both considered to be “legal finish” – the personnel responsible are almost always different than the ones involved in every prior step of the process. All too often, however, most of the support, training, capacity building, attention, and funding has gone to this final stage, while the role of the law and legal advisors has been ignored in all the others.

Legal advisors are rarely, if ever, part of the process of monitoring and surveilling the maritime domain, analyzing anomalies, sharing information, planning operations, or even executing operations. They are sometimes – but rarely – consulted regarding evidence collection and preservation. Usually, the first time lawyers are brought into the maritime security cycle is for the legal finish, and it is left to them to kick-save any legal mistake or oversight that has been made at any previous point in the cycle. There is only so much, however, that can be fixed at the end of the process. Additionally, there may have been operational options that would have been more impactful if legal consultations had occurred earlier. Maritime law is strange and it affords some rights and opportunities that are sometimes hard to believe. Operators may miss out on more effective operations due to a lack of legal input at that stage.

Because maritime law enforcement is a cycle rather than a linear process, it does not end if one of the steps breaks down or even if all of them are successful through to prosecution. The final step is to revisit the starting point – the law – to ensure that it is fit for purpose. Law has two main functions: to constrain bad action and to enable good. If the law does not address an undesirable activity occurring in the maritime domain, it should be expanded or amended. If that law is not creating space for “good,” economically productive, and desirable activities, it should also be amended. While maritime law enforcement focuses on “the bad,” governing the maritime domain requires recognizing a balance between the two. Only stamping out the bad is not possible; there must be ample opportunities for good, lawful activities as well – especially when they are vital to a state’s economic security.

To be most effective, therefore, in both promoting good activities and stopping bad ones, the law must be seen as a tool or an asset for law enforcement – much the way a ship, radar system, or even a weapon would be seen. To be as impactful as possible, the law must be calibrated for the security operating environment. But even perfect law will be virtually worthless unless those who understand it and know how to use it are involved from the start of the maritime security cycle. Relegating the law to the legal finish phase betrays a lack of appreciation for the centrality of the law to the entire cycle, and sets up the state for failure.

Legal finish is incredibly important. But so is the legal start. If operational lawyers are not recognized as playing a vital role in all the phases leading up to the handover to land-based authorities, the prospects of both effective operations and successful legal finish are being undermined. So, for all the good attention that has been paid to prosecutors and judges, as well as to the work of coast guard and navy lawyers in support of those prosecutions or administrative proceedings, much more must be done to back up and start integrating sound legal advice throughout the maritime security cycle. While this can be a challenge, as operational cultures tend to not be welcoming to legal advisors, it is not about disrupting missions and operations with annoying legal points. It is about enhancing missions and operations by safeguarding the likelihood of their success. As simple as it sounds, we must not lose sight of the reality that legal finish needs a legal start.

Dr. Ian Ralby is a recognized expert in maritime and resource security. He has worked in more than 95 countries around the world, often assisting them with developing their maritime domain awareness capacity. He holds a JD from William & Mary and a PhD from the University of Cambridge.

Featured Image: A commercial ship passes by San Francisco. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

It is for these very reasons that the CRFM and RSS have been holding fisheries prosecution and interdiction courses that bring the understanding of law to the interdictors; to ensure that the “legal start” is as good/efficient as practicable

Hi Ian; could you expand on why you have stated that persons are not arrested at Sea. My understanding is that powers of arrest generally extend within the jurisdiction of the coastal state when arrest powers extend to TTW ( 12 nautical miles).

The powers may exist in different jurisdictions, but the general approach throughout the world is to detain at sea and handover for arrest on land. The pragmatic reason for this is often a matter of time-limits for presentment. States often have a 24, 48 or 72 hour time limit for presenting a suspect who has been arrested before a court. If they are arrested offshore, that time limit can be eclipsed before it is physically possible to get to a court. There are other reasons, as well, but that is the main driver behind this general policy.

I believe there should be a SOP drawn and should be designed to reflect the critical processes to follow to maintain the legality of the work done from the start stage to the legal finish stage. If more than 1 agency is involved then the SOP should reflect the jurisdictional powers and authority each affected agency have over the identified undesirable, illegal anomalies. Maritime lawyers should be involved in the drawing of this SOP and should reflect all the known anomalies and they should strongly involved in training officers on this Maritime SOP