These republished selections originally featured in the report, “Incubators of Sea Power: Vessel Training Centers and the Modernization of the PLAN Surface Fleet,” published by the China Maritime Studies Institute of the U.S. Naval War College. These selections are republished with permission.

By Ryan D. Martinson

Basic training conducted at Vessel Training Centers (VTCs) is essential to PLAN preparations for high-end conflict in maritime East Asia, which is the primary focus of China’s current military strategy. The surface force, working in conjunction with PLAN aviation, submarines, and coastal defense missile batteries, plus relevant units from the PLA Air Force and PLA Rocket Forces, would be expected to vie for “command of the sea” (制海权) in key operational areas within the first island chain and contest U.S. operations in waters beyond. Yet very little is known about the VTCs charged with helping them prepare to do that. This report seeks to fill this knowledge gap by providing an overview of VTCs— who they are, what they do, and how they do it—and examining some of the main factors affecting their effectiveness.

In particular, this report tracks recent efforts by the PLAN’s VTCs to evolve to meet the requirements of a rapidly expanding and modernizing surface fleet. This expansion/modernization began in the early 2000s, with the development of new classes of destroyers, frigates, and fast attack craft, but has accelerated since Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012. In the last decade, the PLAN has invested massive resources into new construction of advanced surface combatants, from stealthy corvettes intended for “near seas” operations to amphibious assault ships designed to project Chinese naval power throughout the Indo-Pacific and beyond. The PLAN’s embrace of surface warfare has placed huge stresses on the VTCs—to train more ship crews, to keep pace with new technologies and mission sets, and to ensure that training quality matches Beijing’s aspirations for a “world-class” navy. This report argues that despite some enduring challenges, the PLAN’s VTCs have generally succeeded in adapting to these new requirements.

VTCs serve two core missions. The first is to provide “basic training” to crews of newly commissioned surface vessels and older surface vessels that have completed major repairs, upgrades, or extended maintenance and need to be prepared to return to active status. Most classes of PLAN surface ships receive basic training at VTCs. This ranges from fast attack craft to hospital ships, corvettes to cruisers. VTCs are not responsible for training the crews of aircraft carriers. Ships enter VTCs as “Class 2” (二类) vessels (nondeployable) and, assuming they meet all requirements and pass all tests, depart for their operational units as deployable assets (“Class 1,” 一类). The VTCs second core mission is to conduct formal “evaluations” (考核) to ensure that the ship as a whole meets basic standards of readiness and that individual sailors meet the training requirements for their respective posts. These evaluations occur over the course of basic training. Basic training also culminates in a final “comprehensive training evaluation” (全训合格考核) that determines whether or not the ship can be certified for deployment.

The basic training conducted at VTCs is comparable to “Basic Phase” training done by the U.S. Navy’s surface force. VTCs themselves are analogues of the U.S. Navy’s Afloat Training Groups. Like with the U.S. Navy, basic training received at VTCs lays a tactical and technical foundation for the crews of individual ships to conduct more advanced training in conjunction with other ships (“surface action groups,” or ship “formations” in PLAN parlance), other arms of the navy (air, submarine, etc.), and the joint force…

…Ships are “stationed” (驻训) at VTCs for the duration of basic training. This allows the crew to focus entirely on the task at hand and use the dedicated training equipment and facilities available at the VTC. There is no explicit timeline within which basic training must be completed, but in practice it typically takes 6-12 months for a newly-commissioned ship to pass the comprehensive training evaluation. This differs from the U.S. Navy’s basic phase training, which is intended to last precisely 24 weeks (5.5 months).

While each VTC has some latitude to decide how it fulfills its training and evaluation missions, all must strictly adhere to a set of “Outlines on Military Training and Evaluation” (军事训练与考核大 纲, OMTE). The PLA issues a general, military-wide OMTE containing key principles that inform the development of a narrower set of OMTEs for each service.

To date, the PLA has issued three military-wide OMTEs. The first was issued in 2001, going into effect on January 1, 2002. Among other aims, the 2002 OMTE sought to ensure that training evaluations were true assessments of capabilities instead of “theatrical performance.” The 2009 update sought to increase the quantity of combined arms training, focus more on operations in complex electromagnetic environments, augment use of simulators, expand training for non-war military operations, increase “confrontation” (i.e., blue/red) training, and raise standards for basic training. These new requirements directly impacted the policies and approaches of the VTCs. Very little is known about the 2018 OMTE, as the PLA did not allow any media commentary about its contents. Four years later, key themes contained within it remain largely unknown. Each military-wide OMTE begets a separate set of service-specific OMTEs. These documents, in turn, inform the development of OMTEs for different service arms, and in the case of the PLAN surface force, OMTEs for each ship class. VTC instructors adhere to existing OMTEs for ships they are training, and they also help develop OMTEs for new classes of ships.

… Over time, the focus of at-sea training transitions from basic proficiency to handling complex scenarios under stressful situations. The experience of the Type 052D destroyer Qiqiha’er is a case in point. In October 2020, just two months after her commissioning, the Northern Theater Command Navy VTC took the Qiqiha’er out for seven days of training in the Yellow Sea. The training involved 20+ subjects, including firing the ship’s main gun against a surface target (an “enemy frigate”), missile defense (by simulating the firing of the ship’s surface to air missiles and actual firing of its close-in weapons systems—CIWS), man overboard recovery, and underway replenishment.

Basic training at VTCs involves use of live ordnance. Surface combatants fire their main guns against surface targets or targets ashore, CIWS against target drones, rocket-propelled depth charges, and surface-to-air and anti-ship missiles. Ships engaged in at-sea training also use onboard combat systems to simulate the firing of missiles and torpedoes.

Though the focus of basic training is on developing the technical and tactical capabilities of individual ships, VTCs will organize two or more ships to train together at sea, often for several days at a time. For example, in February 2021 the North Sea Fleet VTC took out eight ships for five days of at-sea training in the Yellow Sea. Participants included the Type 056A corvette Zhangjiakou; the Type 052D destroyers Huai’nan, Qiqiha’er, and Tangshan; and the auxiliary Beilan 770.

The composition of training groups changes over time, as some ships complete their training/evaluations and return to the fleet and new ships arrive. For example, in July 2021 the Type 052D destroyer Huai’nan that participated in the February 2021 training event (described in the previous paragraph), departed with another group of ships for six days of training in the Yellow Sea: the Dongpinghu (Type-903A), Kaifeng (052D), Xinji (056A), and Dongying (056A)…

… Despite going out as a group, the focus remains on individual ships. But in some cases, two or more ships in the group will operate together to fulfill training requirements. For example, the preferred PLAN approach to ASW requires multiple ships, aircraft, and other platforms working in close concert. Therefore, ASW training will sometimes involve two or more ships in the group, plus embarked helicopters…

…In at least some, perhaps all, cases, ships engaged in basic training at VTCs conduct more advanced “formation training” (编队训练). This involves members of a task force operating together as a surface action group, synergizing their efforts to complete tasking. For example, in October 2021 the Northern Theater Command Navy VTC took out two Type 052D destroyers (the Huai’nan and the Kaifeng) and three Type 056A corvettes for five days of formation training in the Yellow Sea. While at sea, the five ships practiced joint air defense involving simulated attacks against enemy aircraft, joint fires strikes against enemy-held islands, mine countermeasures, and surveillance and countersurveillance. Video footage of the training shows the ships operating in conjunction with at least one China Coast Guard vessel, demonstrating the ability of VTCs to enlist forces from other services to support training goals. By contrast, the U.S. Navy defers task force and combined arms training until after Basic Phase training is complete.

At-sea training organized by VTCs is designed to be “realistic” (实战化), i.e., to approximate real combat situations. This involves bringing a ship (or small group of ships) to sea and forcing crews to demonstrate mastery of the training subject in unpredictable circumstances. Ships receive orders to leave port to respond to a particular crisis—e.g. the menacing presence of an enemy warship—and must be prepared to cope with threats almost immediately upon departure. Inevitably, the crisis will escalate and the Chinese ship will be ordered to simulate an attack on the enemy combatant. The ship’s crew might also be forced to fend off attack from an enemy aircraft or evade an enemy missile. The purpose of at-sea training is to place crew members under stress to improve their ability to apply skills developed ashore (in simulators) to real world circumstances. These combat scenarios are created by VTC staff members, who also observe and critique the crew’s responses to them.

To further bolster realism, VTCs will sometimes enlist the help of other PLAN units to serve as adversary (i.e., “blue”) forces. For example, while conducting basic training in 2013, the Type 056 corvette Bengbu trained with a PLAN submarine. In December 2015, the Type 052D destroyer Changsha conducted “confrontation” training with PLAN submarines, aircraft, and other ships. The PLAN’s emphasis on “realism” differs from the U.S. Navy’s Basic Phase training, the focus of which is to ensure that crew members develop the technical skills to perform their jobs. While creating “realistic” scenarios is cited as a U.S. Navy training aim, it clearly does not reach the same degree of priority as in the PLAN. In fact, unit-level combat scenarios designed to stress the whole crew only occur during the “Final Battle Problem”—a 2-3 day event at the end of the Basic Phase. Moreover, unlike the PLAN the U.S. Navy does not generally involve real aircraft or submarines to serve as adversary (“red”) forces in the Basic Phase…

Improving Training Quality

At the same time that VTCs have strived to expand capacity, they have also sought to improve the quality of the training they provide. This has not been easy. At the core of this effort has been the development and improvement of a system of “training supervision” (训练监察). Initially, in the early 2000s, this involved the creation of a Training Supervision Department in each VTC, which later evolved into a set of committees charged with the task of monitoring training quality, providing feedback, and (as discussed below) ensuring the integrity of evaluations. Training “supervisors” ( 监察员) point out problems/failings of individual crew members and weaknesses in the performance of the ship as a whole. They record these problems in dossiers, which can be reviewed by the training staff and officers aboard the ship undergoing training so that adjustments can be made. For example, Eastern Theater Command Navy VTC training supervisor Liu Zhiwan (刘志皖) noted eleven specific problems during a 2017 ASW training event. Among these, “the ship CO’s tactical awareness was not strong, the sonar operator lacked a clear mastery of the [tactical] situation, and the towed array was deployed at the wrong time.”

VTCs’ pedagogy has evolved over time to foster better training outcomes. For years, VTCs employed what was called a “nanny style” (保姆式) approach. That meant that VTC instructors did the bulk of actual teaching. This approach resulted in passivity among ship officers and “weakened the initiative” of ship COs. In 2010, the East Sea Fleet VTC, taking its cues from new OMTE requirements, revised its approach by empowering COs to take greater responsibility in organizing training for their ships. This reportedly increased the agency and creativity of the COs. Henceforth, they were responsible for organizing training for “ordinary” training subjects. The CO took the lead, with VTC staff providing assistance. They were also allowed a greater role in the organization of more important training subjects. The new approach, called a “guiding style” (指导式), “fully mobilized the initiative and creativity” of ship COs….

….VTCs have taken steps to ensure a highly-motivated training staff. By 2013, the leaders of the North Sea Fleet VTC, for example, had concluded that the attitudes of instructors assigned there were too lax. The problem was that the job was too “stable,” so that some of them “lacked enterprising spirit.” To stimulate greater zeal for their work, the North Sea Fleet VTC instituted an “incentive mechanism” and began providing extra compensation for high-performing training captains, trainers, and mission area experts.

VTCs have also instituted mechanisms that allow sailors receiving training to provide feedback on particular instructors or instructional practices. For example, the South Sea Fleet VTC invited sailors to complete appraisals of their instructors and mission area experts. Staff members with negative appraisals were reprimanded for their failings. Students dissatisfied with the quality of instruction can also provide feedback directly to training supervisors at the VTC.

Evaluation: Making Sure the Ship is Ready to Fight

Evaluations are the method by which the PLAN ensures that desired levels of technical and tactical training proficiency are reached for all training subjects. They are also seen as an instrument—in their words, a “command stick” (指挥棒)—to force units to train hard and well…

…After the ship passes all subject evaluations, it can proceed to the comprehensive training evaluation. Taking place at sea over the course of two or more days, the comprehensive training evaluation is both a judgment of the competence of the ship’s commanding officer (and other senior officers) and the competence of the ship as a whole. The core focus is on “integrated offense/defense” (综合攻防), i.e. engaging multiple threats from all three domains (air, surface, and subsurface). PLA media coverage of these events often shows footage of the CO and XO in the ship’s CIC, issuing orders to neutralize (or avoid) enemy threats. Behind them stand members of the “evaluation group” (考核组), who judge the correctness of their words and actions given the situations that they face. Other members of the evaluation group are likely dispersed around the ship, observing the performance of other crew members.

During comprehensive training evaluations, surface combatants will live-fire weapons systems including main guns, CIWS, and rocket-propelled depth charges. When engaging aerial threats, they will launch decoys. When engaging enemy submarines, they will simulate the firing of torpedoes.

To mimic real combat conditions, comprehensive training evaluations are unscripted. Ships put to sea without any knowledge of the challenges they will face. Therefore, these events are naturally very stressful for the CO and the crew. PLAN officers often describe the years of preparation and the culminating event as “more difficult than getting a PhD.”

To further increase realism, VTCs will involve outside units to serve as “blue” aggressor forces. For example, in December 2021 the Northern Theater Command Navy VTC organized three ships—the destroyer Harbin and corvettes Xinji and Songyuan—to participate in a 72-hour comprehensive training evaluation. VTC staff members responsible for organizing the evaluation enlisted the participation of other PLAN surface vessels, at least one PLAN submarine, PLAN early warning and strike aircraft, PLAN observation and communications stations, and electronic warfare forces.

Ensuring the Integrity of Evaluations

… The PLAN does not release its OMTEs, so little is known about its standards of proficiency. But it does openly discuss its struggle to ensure rigorous enforcement of its evaluation standards, which has been long and not completely successful.

The first challenge to the integrity of evaluations is institutional. Specifically, groups and individuals who have an interest in high success rates for evaluations have been allowed to play key roles in the evaluation process. Through the 1990s, the task of evaluating training proficiency was the job of VTC staff members in charge of training. In PLAN parlance, “whoever organized training did the evaluations” (谁组训谁考核). This practice was later recognized as hugely problematic, since trainers had a professional interest in seeing high pass rates because it reflected well on them. As a result, “training was not realistic and evaluations lacked rigor” (训练不实、考核不严), and ships judged certified sometimes fell short when conducting real-world operations.

The VTCs took steps to mitigate this problem in the early 2000s. Responsibility for evaluating crew performance was stripped from training staff and assigned to training supervisors (discussed above). Supervisory organizations evolved over time, but the principle remained the same: namely, to “separate training from evaluations” (训考分离). But assigning training and evaluation to different staff members within the same organization is also problematic, since the organization has a strong interest in passing ships that received training there. High success rates reflect well on the training organization. In theory, VTCs have rules preventing senior leaders from directly interfering in evaluation results. However, that has not always stopped them from trying to exert influence. Moreover, members of the evaluation group no doubt feel indirect pressure to act for the benefit of the organization to which they belong.

This conflict of interest was not just a problem in the PLAN. Early in Xi Jinping’s tenure, the PLA recognized that organizations responsible for conducting training should not also be responsible for evaluating training outcomes. Doing so resulted in a lack of focused training, obsession with safety, exercises that were highly scripted (演习念稿子), formalism (形式主义; i.e., focus on image, not substance), and a tendency to fake results (弄虚作假). To remedy this problem, in 2014 the PLA as a whole began embracing principles of training supervision that relied on evaluators external to the organization undertaking training.

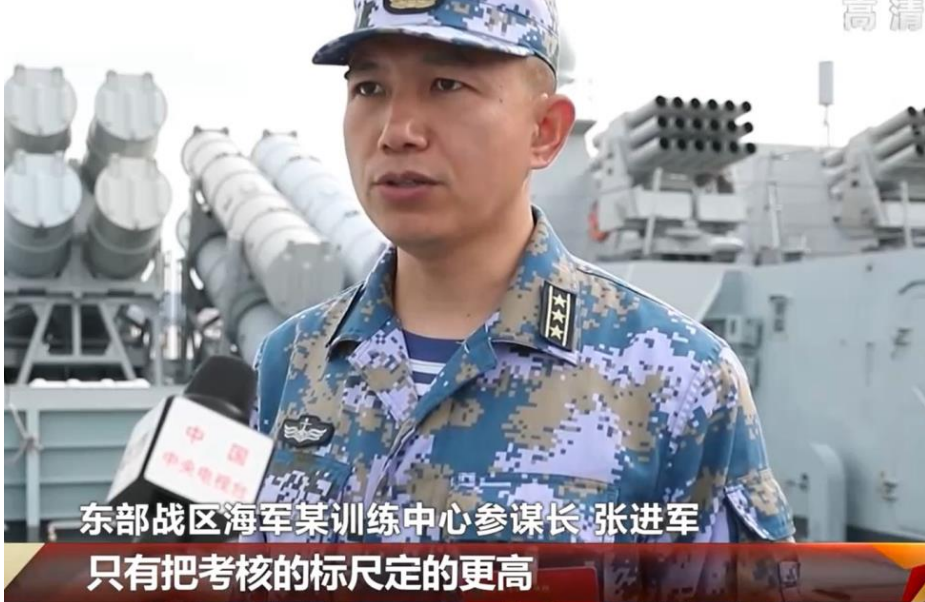

For its part, the PLAN took steps to create “third parties” responsible for supervising comprehensive training evaluations. By 2016, the East Sea Fleet, for example, was organizing third party “joint evaluation groups” (联合考核组) to evaluate officers for ship command. This resulted in more objective evaluations and much higher failure rates. By 2018, the Eastern Theater Command Navy Staff Department had begun sending teams to supervise evaluations of ships that had received training at the VTC. As a result, according to the VTC Deputy Director, Wu Guoyu (吴国瑜), “judgments had become more objective and accurate, and some problems with training had been exposed more prominently.” These accounts suggest that the involvement of the Fleet (now Theater Command Navy) Staff Department has strengthened the integrity of comprehensive training evaluations and improved overall training quality….

….What is clear is that institutional and cultural problems have undermined the PLAN’s efforts to ensure that ship crews actually meet all the training standards outlined in the OMTEs. This is done through formal evaluations over the course of basic training and a final, multi-day comprehensive training evaluation held after basic training is complete. VTCs have strong incentives to give passing marks to all ships/crews that they train, because doing so reflects well on them. However, in recent years the PLAN—following guidance from above—has implemented a system that involves “third party” entities in the evaluation process. These teams of experts from the Theater Command Navy Staff Department are more insulated from institutional pressures to achieve high success rates. By some accounts, this new system is yielding more objective assessments….

…Despite similar timelines, PLAN basic training appears to cover more content than U.S. Navy Basic Phase training. After completing basic training and passing all evaluations, PLAN vessels are expected to be ready for almost immediate deployment, as single ships or as members of “ship formations” (i.e., surface action groups). Therefore, basic training includes subjects such as joint ASW, joint air defense, and joint search and rescue, which the U.S. Navy leaves for later phases in the training process. Moreover, PLAN basic training concludes with a multi-day comprehensive training evaluation that certifies that a ship and its CO are ready for action. The U.S. Navy’s Basic Phase does not.

Lastly, PLAN basic training places much heavier emphasis on training ship crews under “realistic” combat conditions. The aim is to force sailors to demonstrate competence in unpredictable circumstances, under stress, and against “blue” aggressor forces enlisted for the purpose. Except for a 2-3 day capstone Final Battle Problem, reserved until the end of Basic Phase training, the U.S. Navy does not prioritize training under realistic conditions until months later, during follow-on training phases.

Ryan D. Martinson is a researcher in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the Naval War College. He holds a master’s degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a bachelor’s of science from Union College. Martinson has also studied at Fudan University, the Beijing Language and Culture University, and the Hopkins-Nanjing Center.

Featured Image: The guided-missile frigate Xuchang (Hull 536) attached to a destroyer flotilla with the navy under the PLA Southern Theater Command fires its close-in weapon system at mock sea targets during a maritime training exercise in waters of the South China Sea in late March, 2020. (eng.chinamil.com.cn/Photo by Li Hongming and Li Wei)

– Great example of where quantity has a quality of its own. They have enough ships to train against one another blue/red team style.

– Likely they have that little bit of advantage being the new navy should give them. That 30mm CIWS with both EO/IR and Radar directors. Ships are big and can carry big stuff, traditionally an advantage unless posed against shore fortification.